General Assembly Distr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cageprisoners Cageprisoners

CAGEPRISONERS BEYOND THE LAW – The War on Terror’s Secret Network of Detentions AFRICA East Africa PRISON NAME LOCATION CONTROL SITE CONDITIONS DETAINEES STATUS Unknown Unknown East African Arabic Muhammad al-Assad was taken from his - Muhammad al- Suspected speaking jailers, with home in Tanzania and was only told that Assad Proxy Detention possibly Somali or orders had come from very high sources that Facility Ethiopian accents. he should be taken. The next thing he knew he had been taken on a plane for three hours to a very hot place. His jailers who would take him for interrogation spoke Arabic with a Somali or Ethiopian accent and had been served with bread that was typical of those regions. He was held in this prison for a period of about 2 weeks during which time he was interrogated by an English-speaking woman a white western man who spoke good Arabic. 1 Egypt Al Jihaz / State Situated in Nasr State Security Many former detainees have consistently - Ahmad Abou El Confirmed Security City which is in Intelligence approximated that cells within this centre are Maati Proxy Detention Intelligence an eastern roughly four feet wide and ten foot long, with - Maajid Nawaz Facility National suburb of Cairo many packed together, and with many more - Reza Pankhurst Headquarters detainees held within a small area. A torture - Ian Nesbit room is also alleged to be close by to these cells so that detainees, even when not being tortured themselves, were privy to the constant screams of others. Abou Zabel 20 miles from State Security El Maati reports that he spent some weeks in - Ahmad Abou El Confirmed the centre of Intelligence this prison. -

Open Society Justice Initiative | Globalizing Torture

GLOBALIZING TORTURE CIA SECRET DETENTION AND EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION ENDNOTES GLOBALIZING TORTURE CIA SECRET DETENTION AND EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION 2 Copyright © 2013 Open Society Foundations. This publication is available as a pdf on the Open Society Foundations website under a Creative Commons license that allows copying and distributing the publication, only in its entirety, as long as it is attributed to the Open Society Foundations and used for noncommercial educational or public policy purposes. Photographs may not be used separately from the publication. ISBN: 978-1-936133-75-8 PUBLISHED BY: Open Society Foundations 400 West 59th Street New York, New York 10019 USA www.opensocietyfoundations.org FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: Amrit Singh Senior Legal Officer National Security and Counterterrorism [email protected] DESIGN AND LAYOUT BY: Ahlgrim Design Group PRINTED BY: GHP Media, Inc. PHOTOGRAPHY: Cover photo © Ron Haviv/VII 3 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND METHODOLOGY 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 RECOMMENDATIONS 9 SECTION I: INTRODUCTION 11 SECTION II: THE EVOLUTION OF CIA SECRET DETENTION AND 13 EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION OPERATIONS Extraordinary Rendition 13 Secret Detention and “Enhanced Interrogation Techniques” 15 Current Policies and Practices 19 SECTION III: INTERNATIONAL LEGAL STANDARDS APPLICABLE TO 22 CIA SECRET DETENTION AND EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION Torture and Cruel, Inhuman, and Degrading Treatment 23 Transfer to Torture or Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment 25 Arbitrary Detention and Enforced Disappearance 26 Participation in Secret Detention and Extraordinary Rendition Operations 27 SECTION IV: DETAINEES SUBJECTED TO POST-SEPTEMBER 11, 2001, 29 CIA SECRET DETENTION AND EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION SECTION V: FOREIGN GOVERNMENT PARTICIPATION IN 61 CIA SECRET DETENTION AND EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION SECTION VI: CONCLUSION 119 ENDNOTES 120 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was written by Amrit Singh, Senior Legal Officer for the Open Society Justice Initiative’s National Security and Counterterrorism program, and edited by David Berry. -

Guide to the UN Convention Against Torture in South Africa

Guide to the UN Convention against Torture in South Africa By Lukas Muntingh 2011 Guide to the UN Convention against Torture in South Africa By Lukas Muntingh 2011 Civil Society Prison Reform Initiative, Community Law Centre The update and reprint of this document was made possible with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Community Law Centre and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. © CSPRI-Community Law Centre, 2011 Copyright in this publication is vested in the Community Law Centre, University of Western Cape. No part of this article may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express permission, in writing, of the Community Law Centre. It should be noted that the content and/or any opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the CLC, the CSPRI or any funder or sponsor of the aforementioned. Civil Society Prison Reform Initiative (CSPRI) Community Law Centre University of the Western Cape Private Bag X17 7535 SOUTH AFRICA The aim of CSPRI is to improve the human rights of prisoners through research-based lobbying and advocacy, and collaborative efforts with civil society structures. The key areas that CSPRI examines are: developing and strengthening the capacity of civil society and civilian institutions related to corrections; promoting improved prison governance; promoting the greater use of non-custodial sentencing as a mechanism for reducing overcrowding in prisons; and reducing the rate of recidivism through improved reintegration programmes. -

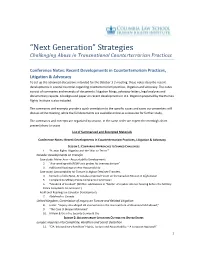

“Next Generation” Strategies Challenging Abuse in Transnational Counterterrorism Practices

“Next Generation” Strategies Challenging Abuse in Transnational Counterterrorism Practices Conference Notes: Recent Developments in Counterterrorism Practices, Litigation & Advocacy To set up the advanced discussions intended for the October 1‐2 meeting, these notes describe recent developments in several countries regarding counterterrorism practices, litigation and advocacy. The notes consist of summaries and excerpts of documents: litigation filings, advocacy letters, legal analyses and documentary reports. A background paper on recent developments in U.S. litigation prepared by the Human Rights Institute is also included. The summaries and excerpts provide a quick orientation to the specific issues and cases our presenters will discuss at the meeting, while the full documents are available online as a resource for further study. The summaries and excerpts are organized by session, in the same order we expect the meeting’s short presentations to occur. List of Summarized and Excerpted Materials Conference Notes: Recent Developments in Counterterrorism Practices, Litigation & Advocacy SESSION 1: COMPARING APPROACHES TO SHARED CHALLENGES 1. “Human Rights Litigation and the ‘War on Terror’” Canada: Developments on Transfer Case study: Maher Arar – Accountability Developments 2. “Arar working with RCMP as it probes his overseas torture” 3. Additional Readings on Arar Accountability Case study: Accountability for Torture in Afghan Detainee Transfers 4. Remarks of Alex Neve, AI Canada at Special Forum on the Canadian Mission in Afghanistan 5. Complaint to Military Police Complaints Commission 6. “Standard of Conduct” (Written submissions in “Matter of a public interest hearing before the Military Police Complaints Commission”) Additional Readings on Canadian Developments 7. Abdelrazik v. Canada United Kingdom: Commission of Inquiry on Torture and Related Litigation 8. -

Extraordinary Rendition in International Law: Criminalising the Indefinable?

Extraordinary rendition in international law: criminalising the indefinable? by Jeanne-Mari Retief Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree LLD in the Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria January 2015 Supervisor: Professor CJ Botha Annexure G University of Pretoria Declaration of originality This document must be signed and submitted with every essay, report, project, assignment, mini-dissertation, dissertation and/or thesis . Full names of student: Jeanne-Mari Retief Student number: 04346386 / 24100049 Declaration 1. I understand what plagiarism is and am aware of the University’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this thesis (eg essay, report, project, assignment, mini-dissertation, dissertation, thesis, etc.) is my own original work. Where other people’s work has been used (either from a printed source, Internet or any other source), this has been properly acknowledged and referenced in accordance with departmental requirements. 3. I have not used work previously produced by another student or any other person to hand in as my own. 4. I have not allowed, and will not allow, anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as his or her own work. Signature of student:....……………………………………………………………………………...... Signature of supervisor:………………......………………………………………………………….. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Christo Botha, for believing in this topic as much as I did. Thank you for the unwavering support and for sharing the passion toward extraordinary rendition. This thesis is dedicated to you. I would also like to thank my husband for his support, the late night debates, and for encouraging me when I doubted myself and the strength of my arguments. -

Policing Mechanisms to Counter Terrorist Attacks in South Africa

POLICING MECHANISMS TO COUNTER TERRORIST ATTACKS IN SOUTH AFRICA by RUFUS KALIDHEEN Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MAGISTER TECHNOLOGICAE (Policing) SCHOOL OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF. R. SNYMAN MARCH 2008 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Greatness is not where we stand, but in what direction we are moving. We must sail sometimes in the wind and sometimes against it – but sail we must and not drift, nor lie at anchor – Oliver Wendell Holmes Certainly, completing this thesis has been a rite of passage into realm of self-knowledge, and I could not have achieved this success without the encouragement and support of the following people: • Professor Rika Snyman: for her encouragement for the completion of this thesis. • My family: many thanks to my family who have accommodated my absence in the fulfilment of this thesis. • My Editor: thanks for your constant encouragement, support and guidance. • Senior executive members of the SAPS: my thanks to your support in the form of access to the ambits of the service. • Ernest and Dumi: thanks for your words of encouragement throughout my study. This thesis is dedicated to ‘DJ’ and the belief that ‘impossible is nothing’. ii DECLARATION I, Rufus Kalidheen (student number: 36788333), hereby declare that ‘Policing Mechanisms to counter terrorist attacks in South Africa’ is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted, have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ………………………….. …………………….. R. Kalidheen Date iii ABSTRACT Terrorism remains a cardinal threat to national, regional, and international peace and security.