Fossils Are Not the Same: Different Fossils Are Formed in Different Ways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Early Miocene of Southeastern Wyoming Robert M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of 2002 New Amphicyonid Carnivorans (Mammalia, Daphoeninae) from the Early Miocene of Southeastern Wyoming Robert M. Hunt Jr. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Hunt, Robert M. Jr., "New Amphicyonid Carnivorans (Mammalia, Daphoeninae) from the Early Miocene of Southeastern Wyoming" (2002). Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 546. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub/546 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10024 Number 3385, 41 pp., 28 ®gures, 4 tables December 27, 2002 New Amphicyonid Carnivorans (Mammalia, Daphoeninae) from the Early Miocene of Southeastern Wyoming ROBERT M. HUNT, JR.1 CONTENTS Abstract ....................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................... -

Miocene Development of Life

Miocene Development of Life Jarðsaga 2 - Saga Lífs og Lands - Ólafur Ingólfsson Thehigh-pointof theage of mammals The Miocene or "less recent" is so called because it contains fewer modern animals than the following Pliocene. The Miocene lasted for 18 MY, ~23-5 MY ago. This was a huge time of transition, the end of the old prehistoric world and the birth of the more recent sort of world. It was also the high point of the age of mammals Open vegetation systems expand • The overall pattern of biological change for the Miocene is one of expanding open vegetation systems (such as deserts, tundra, and grasslands) at the expense of diminishing closed vegetation (such as forests). • This led to a rediversification of temperate ecosystems and many morphological changes in animals. Mammals and birds in particular developed new forms, whether as fast-running herbivores, large predatory mammals and birds, or small quick birds and rodents. Two major ecosystems evolve Two major ecosystems first appeared during the Miocene: kelp forests and grasslands. The expansion of grasslands is correlated to a drying of continental interiors and a global cooling. Later in the Miocene a distinct cooling of the climate resulted in the further reduction of both tropical and conifer forests, and the flourishing of grasslands and savanna in their stead. Modern Grasslands Over one quarter of the Earth's surface is covered by grasslands. Grasslands are found on every continent except Antarctica, and they make up most of Africa and Asia. There are several types of grassland and each one has its own name. -

Willow H. Nguy1, Jacalyn M. Wittmer1, Sam W. Heads2, M. Jared Thomas2

Willow H. Nguy1, Jacalyn M. Wittmer1, Sam W. Heads2, M. Jared Thomas2 1Department of Geology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 605 East Springfield Avenue, Champaign, Illinois 2 61820; Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1816 South Oak Street, The bones are beautifully preserved, but exhibit the typical preservation The rediscovery of an exceptional fossil bone bed from a Champaign, Illinois 61820 techniques of the times. The bone bed was excavated upside-down and then condemned university building has led to a revival of vertebrate covered in thick layers of shellac which discolors and becomes brittle over paleontology in the Department of Geology at the University of time. The entire specimen was then plastered into a mount. Both plaster Illinois Urbana-Champaign. This has been realized through a and shellac are damaging to the fossil and required that the fossil be conservation effort for the historically significant specimen and Cranium 2 and conserved quickly. a paleobiological study. The specimen was collected over fifty Side C mandible 2 years ago by Harold R. Wanless from an unspecified Miocene Steps to Preparation locality near Agate Springs, Nebraska. No other information was 1. Matrix is fully removed and bone is carefully lifted out of bone bed included in notes or on the display label. 2. Shellac is dissolved with acetone or ethanol 3. Softened shellac is removed in layers with dental picks and toothbrushes 4. Broken pieces are repaired with Paleobond PB100 5. Internal structure is strengthened by PaleoBond PB002- penetrant stabilizer 6. Cavity mount is made out of Ethafoam to safely and securely hold the curated specimen. -

Sexual Dimorphism and Mortality Bias in a Small Miocene North American Rhino, Menoceras Arikarense

J Mammal Evol (2007) 14:217–238 DOI 10.1007/s10914-007-9048-4 Sexual Dimorphism and Mortality Bias in a Small Miocene North American Rhino, Menoceras arikarense: Insights into the Coevolution of Sexual Dimorphism and Sociality in Rhinos Matthew C. Mihlbachler Received: 23 February 2007 /Accepted: 23 April 2007 / Published online: 11 October 2007 # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract Rhinos are the only modern perissodactyls that possess cranial weapons similar to the horns, antlers and ossicones of modern ruminants. Yet, unlike ruminants, there is no clear relationship between sexual dimorphism and sociality. It is possible to extend the study of the coevolution of sociality and sexual dimorphism into extinct rhinos by examining the demographic patterns in large fossil assemblages. An assemblage of the North American early Miocene (∼22 million years ago) rhino, Menoceras arikarense, from Agate Springs National Monument, Nebraska, exhibits dimorphism in incisor size and nasal bone size, but there is no detectible dimorphism in body size. The degree of dimorphism of the nasal horn is greater than the degree of sexual dimorphism of any living rhino and more like that of modern horned ruminants. The greater degree of sexual dimorphism in Menoceras horns may relate to its relatively small body size and suggests that the horn had a more sex-specific function. It could be hypothesized that Menoceras evolved a more gregarious type of sociality in which a fewer number of males were capable of monopolizing a larger number of females. Demographic patterns in the Menoceras assemblage indicate that males suffered from a localized risk of elevated mortality at an age equivalent to the years of early adulthood. -

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Paleontological Resources Management Plan (Public Version)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 9-2020 Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Paleontological Resources Management Plan (Public Version) Scott Kottkamp United States National Park Service, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Vincent L. Santucci United States National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division Justin S. Tweet United States National Park Service Jessica De Smet University of Oregon Ellen Stark United States National Park Service, Badlands National Park Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark Part of the Environmental Education Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Fire Science and Firefighting Commons, Leisure Studies Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, Other Life Sciences Commons, Paleontology Commons, Physical and Environmental Geography Commons, Public Administration Commons, and the Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons Kottkamp, Scott; Santucci, Vincent L.; Tweet, Justin S.; De Smet, Jessica; and Stark, Ellen, "Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Paleontological Resources Management Plan (Public Version)" (2020). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 238. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/238 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park -

Fossil Mammals of Florida •Background •Miocene •Pliocene •Pleistocene Background • During the Break up of Pangea, Florida Left Africa and Joined N

Fossil Mammals of Florida •Background •Miocene •Pliocene •Pleistocene Background • During the break up of Pangea, Florida left Africa and joined N. America • Dinosaurs were roaming the Earth, but sadly, Florida was underwater • During this time, mammals were also roaming the Earth (tiny little things who spent most of their time trying not to be crushed under sauropod feet) • After the dinosaurs meet their untimely demise, those pesky mammals flourish The Paleogene • The Paleogene includes the first three epochs of the Cenozoic (Paleocene, Eocene, Oligocene) • The Paleogene was a watery time for Florida • During of the middle of the last epoch of the Paleogene (the Oligocene), roughly 35 Mya, Florida began to emerge • There are some terrestrial fossils, but they are few and far between The Neogene • Made up of the remaining epochs of the Cenozoic – Miocene, Pliocene, Pleistocene and Holocene • Mammals have diversified greatly in the post- dino world. By the Neogene they come in all makes and models. Oligocene to Pleistocene • The Horse ▫ Can see the transition from browsing (O-Late M) to grazing (Late M-present) ▫ Can also see transition from three toes to one toe (aka – a hoof) ▫ This lineage has been historically important to the study of evolution, and is still widely stude ▫ http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fhc/ Olg. To Pleist. • Mesohippus Olg. To Pleist. Miocene (“Less New”) • 23 – 5.33 Mya • This is a time when grazing animals diversified, and by the end of the epoch had reached their heydey – exploiting expanding grasslands • This is really good for paleontologists – animals that tend to live in large groups also have a habit of dying together in large groups • Why do we care about lots of specimens of one species? Miocene in N. -

Agate Fossil Beds

Here at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument are I concentrated the fossils of animals in beds of sedi o 1/3 mentary rock, formed, about 19 million years ago, i by the compression of mud, clay, and erosional mate &u rials deposited by the action of water and wind. These a a& species of animals, then so numerous, have long been & extinct. The beds, which acquired their name from i their proximity to rock formations containing agates, are under the grass-covered Carnegie and University Hills. From the summits of these hills, named by t Nineteen million years ago o AGATE FOSSIL BEDS early collecting parties, you can look down on the c Si lazy meanders of the Niobrara River, 200 feet below. to. strange creatures walked Early pioneers of scientific research in the West I centered many of their activities here. Capt. James H. o Cook was the first white man to discover fossil bones at Agate Fossil Beds, about 1878. Since then, bones '? a Miocene savanna. from the site have been exhibited throughout the h world. Captain Cook and his son, Harold, made Agate >0) Careful digging Springs Ranch a headquarters for paleontologists and a acquired an excellent fossil collection. at these quarries AGATE FOSSIL BEDS TODAY Scientists estimate that at least 75 percent of the has brought to light fossil-bearing parts of the hills are unquarried. The Miocene fossil mammal bones are extremely abun dant, comprise a variety of different species, and are the bones of these animals remarkably well preserved, with numerous complete skeletons. Except for livestock that graze on the hills which relieve the comparatively flat open valley of the Niobrara River, the scene is relatively undisturbed. -

(Chiroptera: Natalidae) from the Early Miocene of Florida, with Comments on Natalid Phylogeny

Journal of Mammalogy, 84(2):729±752, 2003 A NEW BAT (CHIROPTERA: NATALIDAE) FROM THE EARLY MIOCENE OF FLORIDA, WITH COMMENTS ON NATALID PHYLOGENY GARY S. MORGAN* AND NICHOLAS J. CZAPLEWSKI New Mexico Museum of Natural History, 1801 Mountain Road NW, Albuquerque, NM 87104, USA (GSM) Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/84/2/729/2373805 by guest on 29 September 2021 Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73072, USA (NJC) We describe a new extinct genus and species of bat belonging to the endemic Neotropical family Natalidae (Chiroptera) from the Thomas Farm Local Fauna in northern peninsular Florida of early Miocene age (18±19 million years old). The natalid sample from Thomas Farm consists of 32 fossils, including a maxillary fragment, periotics, partial dentaries, isolated teeth, humeri, and radii. A proximal radius of an indeterminate natalid is reported from the I-75 Local Fauna of early Oligocene age (about 30 million years old), also from northern Florida. These fossils from paleokarst deposits in Florida represent the 1st Tertiary records of the Natalidae. Other extinct Tertiary genera previously referred to the Natalidae, including Ageina, Chadronycteris, Chamtwaria, Honrovits, and Stehlinia, may belong to the superfamily Nataloidea but do not ®t within our restricted de®nition of this family. Eight derived characters of the Natalidae sensu stricto are discussed, 5 of which are present in the new Miocene genus. Intrafamilial phylogenetic analysis by parsimony of the Natal- idae suggests that the 3 living subgenera, Natalus (including N. major, N. stramineus, and N. tumidirostris), Chilonatalus (including C. -

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: Geologic Resources Inventory Report John Graham National Park Service

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 2009 Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: Geologic Resources Inventory Report John Graham National Park Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark Part of the Geology Commons, Paleontology Commons, and the Stratigraphy Commons Graham, John, "Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: Geologic Resources Inventory Report" (2009). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 151. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/080 THIS PAGE: Fossil diorama at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, an omnivorous entelodont (Daeodon or Dinohyus) stands over a chalicothere (Moropus), Agate Fossil Beds NM. ON THE COVER: University Hill on the left and Carnegie Hill on the right, site of the main fossil excavations, Agate Fossil Beds NM. NPS Photos. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/080 -

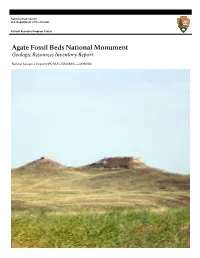

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/080 THIS PAGE: Fossil diorama at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, an omnivorous entelodont (Daeodon or Dinohyus) stands over a chalicothere (Moropus), Agate Fossil Beds NM. ON THE COVER: University Hill on the left and Carnegie Hill on the right, site of the main fossil excavations, Agate Fossil Beds NM. NPS Photos. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/080 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 March 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters. -

The American Genus Penetrigonias Tanner & Martin, 1976 (Mammalia: Rhinocerotidae) As a Stem Group Elasmothere and Ancestor of Menoceras Troxell, 1921

Zitteliana A 52 (2012) 79 The American genus Penetrigonias Tanner & Martin, 1976 (Mammalia: Rhinocerotidae) as a stem group elasmothere and ancestor of Menoceras Troxell, 1921 Kurt Heissig Zitteliana A 52, 79 – 95 Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologe und Geologie, Richard Wagner Str. 10, München, 23.05.2012 D-80333 Munich, Germany Manuscript received E-mail: [email protected] 03.02.2012; revision accepted 17.04.2012 ISSN 1612 - 412X Abstract A detailed character study of the early Oligocene skull of Penetrigonias dakotensis (Peterson, 1920) kept in the Bavarian State Collec- tion of Paleontology and Geology at Munich, Germany, and comparisons of this specimen with geologically older species of the genus has resulted in the recognition of features characterizing this lineage of small-sized rhinoceroses of North America. Morphological trends recognizable in the upper cheek teeth of P. dakotensis are present also in the early Elasmotheriini, suggesting that the genus Penetrigonias may represent a stem group representative of this tribe. At the same time, the more advanced characters of the latest early Oligocene species P. dakotensis suggest that the genus Menoceras with its Eurasian and American species may represent the successor of this species. A cladistic analysis of the characters of early Rhinocerotidae from America results in a scheme explaining how and when this family may have split into its different tribes. Key words: Elasmotheriini, North America, Menoceras, Penetrigonias, Paleogene, Phylogeny, Rhinocerotidae Kurzfassung Eine genaue Untersuchung des unteroligozänen Schädels von Penetrigonias dakotensis (Peterson, 1920) in der Bayerischen Staats- sammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie und Vergleiche mit älteren Arten der Gattung erlauben es, den typischen Merkmalsbestand die- ser phyletischen Linie kleinwüchsiger Nashörner Nordamerikas zu erfassen. -

3 1 Ttlf**,St--1 14*

4 + I. 1 ..1 T * - R__r E-~~ 7- «~1~/9.H,~r- - ir- Frt hz {,-:-»~ rr#Ir· rh ""Xprrf *31**~ 1 1=6 -< 11~ - J J_= r Al ./FAM U P.Ati'... of the FLORIDA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY UNGULATES OF THE TOLEDO BEND LOCAL FAUNA (LATE ARIKAREEAN, EARLY MIOCENE), TEXAS COASTAL PLAIN L. Barry Albright III Volume 42 No. 1 pm 1-80 1999 11,1 , . 34,1·4/3 611 2%51ttlf**,St--1 u 14*-# - ~-*'* UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY are published at irregular intervals. Volumes containtabout,3005pages andrm.not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. JOHNF. EISENBERG, EDITOR RICHARD FRANZ, CO-EDITOR RHODA J. BRYANT, MANAGING ED#OR Communicatibns concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all manuscripts should be addressed to: Managing Editor, Bulletin; Florida Museum of Natural History; University of Florida; P. O. Box 117800, Gainesville FL 32611-7800; U.S.A. This journal is printed on recycled paper. ISSN: 0071-6154 CODEN: BF 5BA5 Publication date: 8-12-99 Price: $ 7.50 UNGULATES OF THE TOLEDO BEND LOCAL FAUNA (LATE ARIKAREEAN, EARLY MIOCENE), TEXAS COASTAL PLAIN L. Barry Albright IIIl ABSTRACT The Toledo Bend Local Fauna includes the most diverse assemblage of mammals yet reported from the earliest Miocene Gulf Coastal Plain. Faunal affinities with the Buda Local Fauna of northern Florida, as well as with faunas of the northern Great Plains and Oregon, suggest a "medial" to late Arikareean age. Of 26 mammalian taxa represented, the 17 ungulates are discussed in this report; the carnivores, small mammals, and lower vertebrates are discussed elsewhere.