Tripartite Round Table on Pension Trends and Reforms (30 November–2 December and 4 December 2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transport Pricing and Accessibility

Transport Pricing and Accessibility Ken Gwilliams | June 2017 Table of Contents Executive summary .............................................................................3 6. Subsidizing ‘goods’: Demand-side interventions .................29 Introduction ...........................................................................................4 7. The effects of taxing ‘bads’ ............................................................33 1. Accessibility, investment, and transport pricing .................7 Conclusion ..............................................................................................37 2. Transport pricing interventions and cash transfers .............6 References ...............................................................................................41 3. The complex objectives of transport pricing .........................12 Endnotes..................................................................................................45 4. Appraising subsidies .......................................................................18 5. Subsidizing ‘goods’: supply-side interventions .....................23 Developing a Common Narrative on Urban Accessibility: 3 Transport Pricing and Accessibility Executive summary A common criticism of urban transport strategies is that they unless accompanied by other measures such as land use are unduly concerned with mobility or the ability to move changes and revolutionized investment criteria, to make it so. rather than accessibility in which a desired journey -

Lycian Way Accommodation

Lycian Way Accommodation Stage Location Accommodation Name Owner Contact Number e-mail Location Info 0 Fethiye Yıldırım Guest House Ömer Yapış 543-779-4732/252-614-4627 [email protected] road close to east boat harbour 1 Ovacik Sultan Motel Unal Onay 252-616-6261 [email protected] Between Ovacik and Olu Deniz Faralya Montenegro Motel Bayram 252-642-1177/536-390-1297 Faralya village center George House Hasan 252-642-1102/535-793-2112 [email protected] Faralya village center Water Mill Ferruh 252-642-1245/252-612-4650 [email protected] Above village 1 Melisa Pension Mehmet Kole 252-642-1012/535-881-9051 [email protected] Below road at village entrance Kabak Armes Hotel Semra Laçin 532-473-1164/252-642-1100 [email protected] of the village below the road Mama's Restaurant Nezmiye Semerci 252-642-1071 Kabak village Olive Garden Fatih Canözü 252-642-1083 [email protected] Below Mama's 2 Turan's Tree Houses Turan 252-642-1227/252-642-1018 Behind Kabak beach Alinca Bayram Bey Bayram 252-679-1169/535-788-1548 Second house in the village 3 Alamut Şerafettin/Şengül 252-679-1069/537-596-6696 info@alamutalınca.com 500 meters above village Gey Bayram's House Bayram/Nurgul 535-473-4806/539-826-7922 [email protected] Right side, 300 meters past pond Dumanoğlu Pension Ramazan 539-923-1670 [email protected] Opposite Bayram's Yediburunlar Lighthouse Sema 252-679-1001/536-523-5881 [email protected] Outside the village 4b GE-Bufe Tahir/Hatice 539-859-0959 On corner in centre of village 4a/b -

List of Hotels, Pension Houses & Inns W

LIST OF HOTELS, PENSION HOUSES & INNS W/ ROOMRATES Bacolod City NAME OF HOTEL ADDRESS TELEPHONE ROOM TYPE RATE 034-433-37- L'Fisher Hotel Main 14th Lacson St. Bacold City 30 Deluxe (single or double) 2,450.00 to 39 Super Deluxe (single 034-433-72- 81 or double) 3,080.00 Matrimonial Room 3,500.00 L' Fisher Chalet Budget Room 1,500.00 Economy 2pax 1,900.00 Economy 3pax 2,610.00 Standard Room 2pax 2,250.00 Standard Room 3pax 2,960.00 Family Room (4) 4,100.00 034-432-36- Saltimboca Tourist & Rest. 15th Lacson St. Bacolod City 17 Standard Room A 800.00 034-433-31- ( fronting L' Fisher Hotel) 79 Satndard Room B 770.00 Std. Room C 600.00 Std. Room D 900.00 Garden Executive 1,300.00 Deluxe 1 1,000.00 Deluxe 2 1,000.00 Single Room 1 695.00 Single Room 2 550.00 Blue Room 900.00 Family Room 1,400.00 extra person/bed 150.00/150.00 034-433-33- Pension Bacolod & Rest. No. 27, 11th St. Bacolod City 77 Single w/ tv & aircon. 540.00 034-432-32- (near L' Fisher Hotel) 31 Dble w/ TV & aircon. 670.00 034-433-70- 65 Trple w/ TV & aircon 770.00 034-435-57- Regina Carmeli Pension 13th St. Bacolod City 49 Superior 2 pax, 1 dble bed 700.00 (near L' Fisher Hotel) Superior 2 pax, 2 single beds 750.00 Standard 3 pax 900.00 Deluxe 4 pax 1,350.00 Family 5-6 pax 1,500.00 11th Street Bed & Breakfast 034-433-91- Inn No. -

Pension Reforms in India

• Cognizant 20-20 Insights Pension Reforms in India Pension reforms are yet to benefit a large section of the Indian population. Significant changes on the policy and regulatory fronts, better marketing and better pricing of products can give this sector a much-needed boost. Executive Summary and cost-effective products are available to the population for creating a retirement corpus. Life expectancy has shot up in recent decades. When public pension systems were first estab- lished, people could typically look forward to only Background of Pension Reforms a few years of retirement if any. Today, globally, India does not have a universal social security sys- the probability of a newborn boy surviving until tem. A large number of India’s elderly are not cov- age 65 is over 80%; the figure is over 90% for ered by any pension scheme. Pension reforms and a girl child. Aging populations are “a high-class” a pension system with greater reach will not only problem, said U.S. President Bill Clinton in his ensure citizens’ welfare in their golden years but 1999 State of the Union address. He continued: will also help the central and state governments “It’s the result of something wonderful: the fact cut their future liabilities. With these broad objec- that we are living a lot longer.” Nevertheless, tives in mind, the government of India set up an there is no denying that aging populations pose expert committee in 1998 to devise a new pension significant challenges for economic, social and system for India. Project Oasis, which was chaired health policies in general and pension systems in by S.A. -

Resort Weeks Calendar

Resort Weeks Calendar CLUB RESORTS SS—SPECIAL SEASON LS—LEAF SEASON UR—ULTRA RED SEASON HR—HIGH RED SEASON R—RED SEASON CLUB ASSOCIATE RESORTS W—WHITE SEASON B—BLUE SEASON January February March April May June July August September October November December ARIZONA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 Cibola Vista Resort and Spa ALABAMA Paradise Isle Resort Shoreline Towers ARUBA La Cabana Beach Resort & Casino CALIFORNIA The Club at Big Bear Village COLORADO The Innsbruck Aspen FLORIDA GULF COAST Bluegreen at Tradewinds Landmark Holiday Beach Resort Mariner’s Boathouse & Beach Resort Ocean Towers Beach Club Panama City Resort & Club Resort Sixty-Six Surfrider Beach Club Tropical Sands Resort Via Roma Beach Resort Winward Passage Resort CENTRAL FLORIDA Casa Del Mar Beach Resort Daytona SeaBreeze Dolphin Beach Club Fantasy Island Resort II The Fountains Grande Villas at World Golf Village Orlando’s Sunshine Resort—Phase I Orlando’s Sunshine Resort—Phase II Outrigger Beach Club SOUTH FLORIDA & THE KEYS Gulfstream Manor The Hammocks at Marathon Solara Surfside GEORGIA The Studio Homes at Ellis Square Petit Crest & Golf Club Villas at Big Canoe HAWAII Pono Kai Resort ILLINOIS Hotel Blake LOUISIANA Bluegreen at Club La Pension The Marquee MASSACHUSETTS The Breakers Resort The Soundings at Seaside Resort MICHIGAN Mountain Run at Boyne MISSOURI The Falls Village Paradise Point Bluegreen Wilderness Club at Big Cedar The Cliffs at Long -

Angola Social Protection Public Expenditure Review (PER)

Angola Social Protection Public Expenditure Public Disclosure Authorized Review (PER) Public Disclosure Authorized Main Report June 21, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized Vice President: Makhtar Diop Country Director: Elisabeth Huybens Practice Manager: Jehan Arulpragasam Task Team Leaders: Andrea Vermehren/Emma Monsalve Montiel Public Disclosure Authorized 0 CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................................... i Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... ii Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... v Chapter 1 Country Context ..................................................................................................................... vii Chapter 2: Social protection spending trends and composition ............................................................. xiv Chapter 3: Pensions ................................................................................................................................. xx Chapter 4: Social safety net programs .................................................................................................. xxv Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................... -

Frequently Asked Questions on National Pension System – All Citizens Model

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ON NATIONAL PENSION SYSTEM – ALL CITIZENS MODEL What is National Pension System? NPS is an easily accessible, low cost, tax-efficient, flexible and portable retirement savings account. Under the NPS, the individual contributes to his retirement account and also his employer can also co-contribute for the social security/welfare of the individual. NPS is designed on Defined contribution basis wherein the subscriber contributes to his account, there is no defined benefit that would be available at the time of exit from the system and the accumulated wealth depends on the contributions made and the income generated from investment of such wealth. The greater the value of the contributions made, the greater the investments achieved, the longer the term over which the fund accumulates and the lower the charges deducted, the larger would be the eventual benefit of the accumulated pension wealth likely to be. Contributions + Investment Growth – Charges = Accumulated Pension Wealth (Individual contribution as well as co-contribution from Employers) Who can Join NPS? Any citizen of India, whether resident or non-resident, subject to the following conditions: Individuals who are aged between 18 – 60 years as on the date of submission of his/her application to the POP/ POP-SP. The citizens can join NPS either as individuals or as an employee-employer group(s) (corporates) subject to submission of all required information and Know your customer (KYC) documentation. After attaining 60 years of age, you will not be permitted to make further contributions to the NPS accounts. Can an NRI open an NPS account? Yes, a NRI can open an NPS account. -

Public Pension Human Resources Organization

PUBLIC PENSION HUMAN RESOURCES ORGANIZATION ROUNDTA B L E 2 0 1 4 O C T O B E R 7 - 8 2 0 1 4 RENAISSANCE SEATTLE HOTEL SEATTLE, WASHINGTON The Public Pension Human Resources Organization Roundtable draws together Human Resources professionals from Public Pension funds throughout the country to learn from industry experts, discuss current issues, and share best practices and ideas from their organizations. Special thanks for coordinating the Roundtable goes to: PUBLIC PENSION HR ORGANIZATION ROUN D T A B L E 2014 AGENDA TUESDAY, OCTOBER 7 8:30—9:00 am Continental Breakfast 9:00—9:15 am Welcome 9:15 —10:15 am What’s Happening in Washington? Neil E. Reichenberg • Executive Director, IPMA-HR Neil will provide us an update on legislative issues in Washington that may affect the HR practice. 10:15—10:30 am Break 10:30—11:00 am Wait...What? A Discussion on Developments in the HR Certification World Neil E. Reichenberg • Executive Director, IPMA-HR 11:00 am—12:00 pm “Open Mic”: Discussion of Critical HR Issues at Each Fund This is your opportunity to gain insight and feedback from experienced colleagues on critical HR is- sues affecting your fund. If you need input, come prepared to present your concern. Topics may in- clude issues within the HR body of knowledge, such as benefits, compensation, employee relations, leadership development, recruiting, etc. 12:00—1:00 pm Lunch (included in conference fee) 1:00—2:00 pm Practitioner Presentation: Building a Constructive Culture Within an Investment Shop Mika Austin • General Manager Human Resources, New Zealand Superannuation Fund The New Zealand Superannuation Fund has been on a mission over the last 3-4 years to turn their culture around towards a collaborative, constructive, truly integrated team approach. -

Proclamation No.152 /2006 the Tourism Proclamation

Proclamation No.152 /2006 The Tourism Proclamation Article 1. Short Title This Proclamation may be cited as “the Tourism Proclamation No.152/2006”. Article 2. Definitions, In this Proclamation, unless the context otherwise requires: (1) “hotel” means an establishment or place, which provides to tourists for fee or reward sleeping accommodation with or without food or beverage and which has no less than ten bedrooms; (2) “tourist supplementary accommodation establishment” means a pension, resort, family pension, a motel, a guest house or furnished apartment a holiday village and a village inn which provides accommodation with or without food or beverages for tourists in return for payment. (3)“restaurant and food catering establishments” means restaurants, buffets, snack bars, tearooms, table d’ hôte, fast food facilities and catering services; (4)“tourist boat” means a pleasure boat available for the transport of tourists for fishing as a sport, for water-sports or pleasure generally; (5)“tourist transport provider” means a person engaged in providing transportation to tourists by means of motor vehicles, including rental of cars, railway, marine vessels of 26 meters length and other means of tourist transportation as prescribed by regulations; (6) “tourist” means a person who stays at least one night in Eritrea, in either private or commercial accommodation, but whose stay does not exceed twelve months and whose main purpose of visit is not to work; (7) “tourism” means the business of providing travel, accommodation, hospitality and -

State Finances Audit Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India

State Finances Audit Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India for the year ended 31 March 2020 Government of Chhattisgarh Report No. 03 of the year 2021 Table of Contents Paragraph Page No. No. Preface -- vii Executive Summary -- ix Chapter I: Overview Profile of the State 1.1 1 Gross State Domestic Product of the State 1.1.1 1 Basis and Approach to State Finances Audit Report 1.2 3 Report Structure 1.3 4 Overview of Government Accounts Structure 1.4 4 Budgetary Processes 1.5 7 Snapshot of Finances 1.5.1 7 Snapshot of Assets and liabilities of the Government 1.5.2 8 Fiscal Balance: Achievement of deficit and total debt targets 1.6 9 Compliance with Provisions of State FRBM Act 1.6.1 9 Medium Term Fiscal Policy Statement 1.6.2 10 Deficit and Surplus 1.6.3 11 Trends of Deficit/Surplus 1.6.4 12 Deficits after examination in Audit 1.6.5 13 Chapter II: Finances of the State Introduction 2.1 15 Sources and Application of Funds 2.2 15 Resources of the State 2.3 17 Receipts of the State 2.3.1 17 Revenue Receipts 2.3.2 18 Trends and growth of Revenue Receipts 2.3.2.1 18 State’s Own Resources 2.3.3 19 Own Tax Revenue 2.3.3.1 20 State Goods and Services Tax (SGST) 2.3.3.2 21 Non-Tax Revenue 2.3.33 22 Central Tax Transfers 2.3.3.4 22 Grants-in-Aid from Government of India 2.3.3.5 23 Fourteenth Finance Commission Grants 2.3.3.6 24 Capital Receipts 2.3.3.7 24 State’s performance in mobilization of resources 2.3.4 25 Application of Resources 2.4 25 Growth and composition of expenditure 2.4.1 26 Revenue Expenditure 2.4.2 28 Major Changes in Revenue Expenditure 2.4.2.1 29 Committed Expenditure 2.4.2.2 29 Undercharged Liability under National Pension System 2.4.2.3 31 Page i State Finances Audit Report for the Year ended 31 March 2020 Table of Contents Paragraph Page No. -

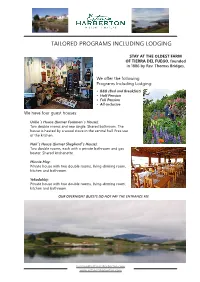

Tailored Programs Including Lodging

TAILORED PROGRAMS INCLUDING LODGING STAY AT THE OLDEST FARM OF TIERRA DEL FUEGO, founded in 1886 by Rev. Thomas Bridges. We offer the following Programs Including Lodging: • B&B (Bed and Breakfast) • Half Pension • Full Pension • All-inclusive We have four guest houses: Uribe´s House (former Foreman´s House): Two double rooms and one single. Shared bathroom. The house is heated by a wood stove in the central hall. Free use of the kitchen. Nail´s House (former Shepherd´s House): Two double rooms, each with a private bathroom and gas heater. Shared kitchenette. Minnie May: Private house with two double rooms, living-dinning room, kitchen and bathroom. Yekadahby: Private house with two double rooms, living-dinning room, kitchen and bathroom. OUR OVERNIGHT GUESTS DO NOT PAY THE ENTRANCE FEE [email protected] www.estanciaharberton.com THE DIFFERENT OPTIONS OF TAILORED PROGRAMS INCLUDING LODGING WE OFFER ARE: Bed and Breakfast Program • Simple breakfast, left at the house the previous night. • Free use of kitchen or kitchenette (depending on the house chosen). • Step back in time during the walking tour of Harberton homes- tead, a National Historical Monument, within regular tour hours. This tour includes the history of the Bridges family and their relationship with the natives, the Park (first nature reserve of Tierra del Fuego), the family cemetery, replicas of yahgan huts, the old-time shearing shed, carpenter´s shop, the boat house (which houses the second oldest boat built in Tierra del Fuego) and the beautiful Main House garden. • Immerse yourself in the depths of the sea during the guided tour of the singular Acatushun Bird and Marine Mammal Museum, within regular tour hours. -

Insights Pt 2019 Exclusive (Government Schemes)

INSIGHTS PT 2019 EXCLUSIVE (GOVERNMENT SCHEMES) May 2018 – January 2019 • www.insightsonindia.com www.insightsias.com INSIGHTS PT 2019 EXCLUSIVE (GOVERNMENT SCHEMES) Table of Contents MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE ................................................................... 6 1.Menstrual Hygiene for Adolescent Girls Schemes ................................................................................. 6 2.Mission Indradhanush ......................................................................................................................... 6 3.Ayushman Bharat–PM Jan Arogya Yojana ............................................................................................ 7 4.Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana (PMSSY) ............................................................................ 8 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE & FARMERS WELFARE ...................................................... 10 1.National Agricultural Higher Education Project (NAHEP) ..................................................................... 10 2.Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana ..................................................................................................... 10 3.Online Portal “ENSURE” ..................................................................................................................... 11 4.Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay SanraksHan Abhiyan (PM-AASHA) ...................................................... 12 MINISTRY OF SKILL DEVELOPMENT & ENTREPRENEURSHIP ...................................... 13