Orange County Growth Management Department Planning Division 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ttt-2-Map.Pdf

BRIDGE RESTRICTIONS - MARCH 2019 <Double-click here to enter title> «¬89 4 2 ESCAMBIA «¬ «¬189 85 «¬ «¬ HOLMES 97 SANTA ROSA ¬« 29 331187 83 610001 ¤£ ¤£«¬ «¬ 81 87 570006 «¬ «¬ 520076 TTT-2 10 ¦¨§ ¤£90 «¬79 Pensacola Inset OKALOOSA Pensacola/ «¬285 WALTON «¬77 West Panhandle 293 WASHINGTON «¬87 570055 ¦¨§ ONLY STATE OWNED 20 ¤£98 «¬ BRIDGES SHOWN BAY 570082 460051 600108 LEGEND 460020 Route with «¬30 Restricted Bridge(s) 368 Route without 460113 «¬ Restricted Bridge(s) 460112 Non-State Maintained Road 460019 ######Restricted Bridge Number 0 12.5 25 50 Miles ¥ Page 1 of 16 BRIDGE RESTRICTIONS - MARCH 2019 <Double-click here to enter title> «¬2 HOLMES JACKSON 610001 71 530005 520076 «¬ «¬69 TTT-2 ¬79 « ¤£90 Panama City/ «¬77 ¦¨§10 GADSDEN ¤£27 WASHINGTON JEFFERSON Tallahassee 500092 ¤£19 ONLY STATE OWNED ¬20 BRIDGES SHOWN BAY « CALHOUN 460051 «¬71 «¬65 Tallahassee Inset «¬267 231 73 LEGEND ¤£ «¬ LEON 59 «¬ Route with Restricted Bridge(s) 460020 LIBERTY 368 «¬ Route without WAKULLA 61 «¬22 «¬ Restricted Bridge(s) 98 460112 ¤£ Non-State 460113 Maintained Road 460019 GULF TA ###### Restricted Bridge Number 98 FRANKLIN ¤£ 490018 ¤£319 «¬300 490031 0 12.5 25 50 Miles ¥ Page 2 of 16 BRIDGE RESTRICTIONS - MARCH 2019 350030 <Double-click320017 here to enter title> JEFFERSON «¬53 «¬145 ¤£90 «¬2 «¬6 HAMILTON COLUMBIA ¦¨§10 290030 «¬59 ¤£441 19 MADISON BAKER ¤£ 370013 TTT-2 221 ¤£ SUWANNEE ¤£98 ¤£27 «¬247 Lake City TAYLOR UNION 129 121 47 «¬ ¤£ ¬ 238 ONLY STATE OWNED « «¬ 231 LAFAYETTE «¬ ¤£27A BRIDGES SHOWN «¬100 BRADFORD LEGEND 235 «¬ Route with -

Orlando Urban Exploration Guide

URBAN EXPLORATION WHERE TO EXPLORE IN AND AROUND THE ORLANDO AREA – INCLUDES HIKING, BIKING, AND PADDLING Recreation Opportunities in Orlando Let’s review the best places to get outside in downtown and suburban Orlando Downtown Adventures TAKE A BUS, A BIKE, OR WALK Gaston Edwards Park Located in Ivanhoe Park Village, Gaston Edwards runs along the shore of Lake Ivanhoe. It offers fitness stations, a sand volleyball court, plenty of shade trees, and a couple docks. You can even launch a paddleboard from the paddleboard-specific dock. The Orlando Urban Trail can also be accessed from the park. Address 1236 N Orange Ave, Orlando, FL 32804 Distance from Downtown 1.5 miles via bike lanes Open Sunrise to Sunset Mead Botanical Gardens Perfect for the plant lover, Mead Gardens has paths all through the garden. Relax at the tranquil ponds or learn about different plant species sprinkled around the park Address 1300 S Denning Dr, Winter Park, FL 32789 Distance from Downtown 4.2 miles via the Orlando Urban Trail Open 8:00AM-7:00PM Greenwood Urban Wetland Greenwood Urban Wetland is one of the best places in downtown Orlando for birdwatching despite its proximity to the highway. The wetland is the perfect home for many native Florida birds. Address 1411 Greenwood St, Orlando, FL 32801 Distance from Downtown 2.4 miles via bike lanes Open Sunrise to Sunset Dickson Azalea Park Dickson Azalea Park offers an oasis for those who want to enjoy its shady trees, picturesque landscape, beautiful birds and flowing water. Frequently a location for those who want a quiet lunch, or a relaxing view, this park is truly one of Orlando’s gems. -

Joint Public Workshop for Minimum Flows and Levels Priority Lists and Schedules for the CFWI Area

Joint Public Workshop for Minimum Flows and Levels Priority Lists and Schedules for the CFWI Area St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) Southwest Florida Water Management District (SWFWMD) South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) September 5, 2019 St. Cloud, Florida 1 Agenda 1. Introductions and Background……... Don Medellin, SFWMD 2. SJRWMD MFLs Priority List……Andrew Sutherland, SJRWMD 3. SWFWMD MFLs Priority List..Doug Leeper, SWFWMD 4. SFWMD MFLs Priority List……Don Medellin, SFWMD 5. Stakeholder comments 6. Adjourn 2 Statutory Directive for MFLs Water management districts or DEP must establish MFLs that set the limit or level… “…at which further withdrawals would be significantly harmful to the water resources or ecology of the area.” Section 373.042(1), Florida Statutes 3 Statutory Directive for Reservations Water management districts may… “…reserve from use by permit applicants, water in such locations and quantities, and for such seasons of the year, as in its judgment may be required for the protection of fish and wildlife or the public health and safety.” Section 373.223(4), Florida Statutes 4 District Priority Lists and Schedules Meet Statutory and Rule Requirements ▪ Prioritization is based on the importance of waters to the State or region, and the existence of or potential for significant harm ▪ Includes waters experiencing or reasonably expected to experience adverse impacts ▪ MFLs the districts will voluntarily subject to independent scientific peer review are identified ▪ Proposed reservations are identified ▪ Listed water bodies that have the potential to be affected by withdrawals in an adjacent water management district are identified 5 2019 Draft Priority List and Schedule ▪ Annual priority list and schedule required by statute for each district ▪ Presented to respective District Governing Boards for approval ▪ Submitted to DEP for review by Nov. -

Ocklawaha River Hydrologic Basin

Why Care Implementing Future Growth Permitting Process Final Design Success Economic Growth often requires new development and/or redevelopment. Schools . Downtown Revitalization Anti-Degradation under Chapter 62-4.242 and 62-302.300, F.A.C and 40D-4.301, F.A.C., require agencies to ensure permits... “will not adversely affect the quality of receiving waters such that the water quality standards will be violated.” 403.067 F.S. Requires Consideration of Future Growth in the Development of BMAPs. Most rely on Anti-Degradation and the “Net-Improvement” Policy. Downstream Protection Protecting Waters = More Stringent Controls = More $ = Higher Project Cost WEEKI WACHEE 1948 WEEKI WACHEE 2013 http://www.slideshare.net/FloridaMemory http://www.tampabay.com/news/business/tourism/ Project/florida-winter-holidays clear-water-mermaids-and-yes-history-at-weeki-wachee- springs/2131164 Preserving Water Quality & Project Specific Requirements Williamson Blvd - road extension project of approximately 2 miles. Located: Port Orange, Volusia County Small section of existing road widening. Multi-use improvement including transportation corridor planning. Soil Conditions: High Groundwater Existing Borrow Pits remain on-site from construction of I-95. Land use change from natural conditions to roadway. Williamson Blvd Project Outfalls to Spruce Creek. Spruce Creek has an adopted Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for Dissolved Oxygen (DO). Spruce Creek Impaired for . Dissolved Oxygen (DO) . Causative Pollutant . Total Phosphorus . BOD Wasteload Allocations (WLA) . NPDES MS4 % Reduction: . 27% TP . 25% BOD . TMDL (mg/L) . 0.16 mg/L TP . 2.17 mg/L BOD Net Improvement is required for Phosphorus. Net Improvement meets: . Anti-Degradation Rules . 403.067 Future Growth . -

State of the Everglades Spring 2016

State of the Everglades Spring 2016 Audubon Florida - 4500 Biscayne Blvd. #205 Miami, FL 33137 Photo by Rod J. Wiley http://www.GivetoAudubonFlorida.org Dear Friends, The ecological problems in the Everglades and our coastal waters are not new. Nor are they easy to solve. Audubon Florida is dedicated to making sure restoration is done right, and is a responsible investment focused on wildlife needs. But we need your help. Photo by: Marjorie Shropshire If the public is united in demanding that Water Quality and Storage Solutions to decision-makers support the Everglades and the coastal estuaries, we can find and commit Ease Florida’s Coastal Water Crisis to practical solutions. Florida’s coastal waters are experiencing an unprecedented ecological Thank you for all that you do. collapse. Fish kills in the Indian River Lagoon, plumes of dark water in the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuaries, and a massive seagrass die-off in Florida Bay are just the latest evidence. Scientists believe this crisis is due to the mismanagement and Eric Draper over-drainage of freshwater off Florida’s mainland combined with Executive Director increased water pollution from fertilizers, sewage, and septic tanks. Water management problems start in Lake Okeechobee – the liquid heart of the Everglades. The Lake’s optimum water level is between 12.5 and 15.5 feet. Higher levels drown out native plant communities and damage foraging, breeding, and nesting habitats for iconic wildlife such as the endangered Everglade Snail Kite. When water levels are high enough Everglades Wading Bird Nesting Decline* to threaten the safety of the aging Herbert Hoover Dike, the U.S. -

Avian Pointe |Fully-Entitled, 480-Unit Multi-Housing Development

FULLY-ENTITLED, 480-UNIT MULTI-HOUSING DEVELOPMENT AVIAN POINTE | SITE IN FAST-GROWING APOPKA (ORLANDO), FLORIDA AVIAN POINTE THE OFFERING Property Overview – Parcel B2 Address: 2995 Peterson Road, Apopka, FL 32703 Holliday Fenoglio Fowler, L.P. is pleased to exclusively offer an exceptional Municipality: Orange County investment opportunity to acquire Avian Pointe (the “Property” or “Site”), Parcel ID: 07-21-28-0000-00-002 a 30-acre development site fronting State Road 429, just south of U.S. Site Area: 30.912 Acres Highway 441 in the high-growth Orlando bedroom community of Apopka, Max Density: 480 Units Florida. Looking ahead, the Apopka region is poised to display accelerated growth upon the completion of the Wekiva Parkway Extension (scheduled Use / Zoning: Multifamily / PD R-1 for 2022) – a 27-mile expressway which will complete the Central Florida Stories / Maximum Height: Four / 50 Feet Beltway encircling the Orlando MSA, enabling Apopka residents to commute seamlessly to highly-coveted areas in Seminole County including Lake Mary, Heathrow, and Sanford, which collectively possess nearly 10 million square feet of office space (roughly the same amount as INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS Downtown Orlando), and are home to major high-wage employers including Deloitte, Verizon, AAA, JPMorgan Chase, BNY Mellon, and LOCATED IN THE DIRECT PATH OF GROWTH IN WEST Convergys, among others. ORLANDO The Site is fully-entitled for 480 apartment units, and represents one PRIME FRONTAGE & VISIBILITY ALONG SR 429; parcel (B2) within the larger Avian Pointe master-planned community ADVANTAGEOUSLY SITUATED IMMEDIATELY SOUTH OF THE (127-acre land assemblage), which possesses full-entitlements for 56 NEW WEKIVA PARKWAY EXTENSION single family homes, 222 townhomes, in addition to another +/- 20 acres of recreational and mixed-use space which allow for a school, boutique hotel, professional office, senior living facility, as well as centralized FULL ENTITLEMENTS IN-PLACE FOR 480 UNITS community amenities such as a resort-style pool, playground, dog park, and a variety of sports fields. -

Appendix 1 U.S

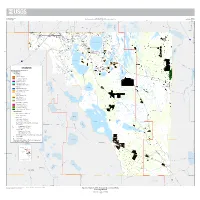

U.S. Department of the Interior Prepared in cooperation with the Appendix 1 U.S. Geological Survey Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Office of Agricultural Water Policy Open-File Report 2014−1257 81°45' 81°30' 81°15' 81°00' 80°45' 524 Jim Creek 1 Lake Hart 501 520 LAKE 17 ORANGE 417 Lake Mary Jane Saint Johns River 192 Boggy Creek 535 Shingle Creek 519 429 Lake Preston 95 17 East Lake Tohopekaliga Saint Johns River 17 Reedy Creek 28°15' Lake Lizzie Lake Winder Saint Cloud Canal ! Lake Tohopekaliga Alligator Lake 4 Saint Johns River EXPLANATION Big Bend Swamp Brick Lake Generalized land use classifications 17 for study purposes: Crabgrass Creek Land irrigated Lake Russell Lake Mattie Lake Gentry Row crops Lake Washington Peppers−184 acresLake Lowery Lake Marion Creek 192 Potatoes−3,322 acres 27 Lake Van Cantaloupes−633 acres BREVARD Lake Alfred Eggplant−151 acres All others−57 acres Lake Henry ! UnverifiedLake Haines crops−33 acres Lake Marion Saint Johns River Jane Green Creek LakeFruit Rochelle crops Cypress Lake Blueberries−41 acres Citrus groves−10,861 acres OSCEOLA Peaches−67 acresLake Fannie Lake Hamilton Field Crops Saint Johns River Field corn−292 acres Hay−234 acres Lake Hatchineha Rye grass−477 acres Lake Howard Lake 17 Seeds−619 acres 28°00' Ornamentals and grasses Ornamentals−240 acres Tree nurseries−27 acres Lake Annie Sod farms−5,643Lake Eloise acres 17 Pasture (improved)−4,575 acres Catfish Creek Land not irrigated Abandoned groves−4,916 acres Pasture−259,823 acres Lake Rosalie Water source Groundwater−18,351 acres POLK Surface water−9,106 acres Lake Kissimmee Lake Jackson Water Management Districts irrigated land totals Weohyakapka Creek Tiger Lake South Florida Groundwater−18,351 acres 441 Surface water−7,596 acres Lake Marian St. -

Lake Kissimmee (WBID 3183B) Nutrient TMDL

CENTRAL DISTRICT • KISSIMMEE RIVER BASIN • UPPER KISSIMMEE PLANNING UNIT FINAL TMDL Report Nutrient TMDL for Lake Kissimmee (WBID 3183B) Woo-Jun Kang, Ph.D., and Douglas Gilbert Water Quality Evaluation and TMDL Program Division of Environmental Assessment and Restoration Florida Department of Environmental Protection December 17, 2013 2600 Blair Stone Road Mail Station 3555 Tallahassee, FL 32399-2400 FINAL TMDL Report: Kissimmee River Basin, Lake Kissimmee (WBID 3183B), Nutrients, December 2013 Acknowledgments This analysis could not have been accomplished without the funding support of the Florida Legislature. Contractual services were provided by Camp Dresser and McKee (CDM) under Contract WM912. Sincere thanks to CDM for the support provided by Lena Rivera (Project Manager), Silong Lu (hydrology), and Richard Wagner (water quality). Additionally, significant contributions were made by staff in the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s Watershed Assessment Section, particularly Barbara Donner for Geographic Information System (GIS) support. The Department also recognizes the substantial support and assistance of its Central District Office, South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD), Polk County Natural Resource Division, and Osceola County, and their contributions towards understanding the issues, history, and processes at work in the Lake Kissimmee Basin. Editorial assistance was provided by Jan Mandrup-Poulsen and Linda Lord. For additional information on the watershed management approach and impaired waters in the -

Lake Apopka Natural Resource Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan

Final Lake Apopka Natural Resource Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan June 2004 Produced by: Industrial Economics, Incorporated 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 For: The United States Fish and Wildlife Service Ecological Services 1875 Century Blvd. Suite 200 Atlanta, GA 30345-3301 With Assistance From: The St. Johns River Water Management District 4049 Reid St Palatka, FL 32177 Final June 2004 This Page Intentionally Left Blank Final June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction......................................................................................................1 1.1 Overview of This DARP........................................................................1 1.2 Overview of North Shore Restoration Area and Lake Apopka .............1 1.3 Farm Buy-out and Bird Mortality Event................................................2 1.4 Authority................................................................................................3 1.5 Coordination with Potentially Responsible Party..................................4 1.6 Public Participation................................................................................5 1.7 Summary of Natural Resource Injuries..................................................5 1.8 Summary of Preferred Restoration Alternative .....................................6 2.0 Natural Resources and Contaminants of Concern .......................................7 2.1 Natural Resources of Concern ...............................................................7 2.2 Contaminants of -

Marshall, Arthur R., the Kissimmee Okeechobee Basin, December 12, 1972

The Kissimmee Okeechobee Basin http://www.gatewaycoalition.org/files/everglades.fiu.edu/marshall/mars... Arthur R. Marshall, Jr. Collection Marshall, Arthur R., The Kissimmee Okeechobee Basin, December 12, 1972. A Report to the Cabinet of Florida Reubin O'D. Askew Governor Richard Stone Secretary of State Robert L. Shevin Attorney General Floyd T. Christian Commissioner of Education Doyle Conner Commissioner of Agriculture Fred O. Dickinson, Jr. Comptroller Thomas D. O'Malley Treasurer December 12, 1972 This report has been produced as a public service by the Division of Applied Ecology, Center for Urban and Regional Studies, University of Miami. The Division of Applied Ecology is funded by the Ford Foundation - Grant No. 710-0132. Second Edition PAGE CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION Arthur R. Marshall 8 HYDROLOGY James H. Hartwell 14 EUTROPHICATION: PROCESS David S. Anthony 21 EUTROPHICATION: HAZARDS John V. Betz 29 MARSH ECOLOGY Ariel E. Lugo 44 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 51 BIBLIOGRAPHY 53 APPENDIX PARTICIPANTS 1 of 37 10/1/2012 3:15 PM The Kissimmee Okeechobee Basin http://www.gatewaycoalition.org/files/everglades.fiu.edu/marshall/mars... ARTHUR R. MARSHALL Ecologist Center for Urban and Regional Studies University of Miami JAMES H. HARTWELL Hydrologist Center for Urban and Regional Studies University of Miami DAVID S. ANTHONY Biochemist University of Florida JOHN V. BETZ Microbiologist University of South Florida ARIEL E. LUG0 Ecologist University of Florida ALBERT R. VERI Environmental Planner Center for Urban and Regional Studies University of Miami SUSAN U. WILSON Biologist Center for Urban and Regional Studies University of Miami I have just returned from south central Florida and the death-bed of an old friend. -

Assessment of Cyanotoxins in Florida's Lakes, Reservoirs And

Assessment of Cyanotoxins in Florida’s Lakes, Reservoirs and Rivers by Christopher D. Williams BCI Engineers and Scientists, Inc. Lakeland, FL. John W. Burns Andrew D. Chapman Leeanne Flewelling St. Johns River Water Management District Palatka, FL. Marek Pawlowicz Florida Department of Health/Bureau of Laboratories Jacksonville, FL. Wayne Carmichael Wright State University Dayton, OH. 2001 Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Harmful algal blooms (HABs) are population increases of algae above normal background levels and are defined by their negative impacts on the environment, the economy, and human health. Historically, many of Florida's largest and most utilized freshwater and estuarine systems have been plagued by occasional blooms of harmful algae. During the last decade, however, the frequency, duration, and concentration levels of these blooms in freshwater and brackish water have increased significantly, primarily due to changes in land utilization, changes in hydrology, increases in nutrient runoff, loss of aquatic vegetation, and a climate that is very conducive to algal growth and proliferation. In 1998, the Florida Harmful Algal Bloom Task Force was established to determine the extent to which HABs pose a problem for the state of Florida. Blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) were identified as top research priorities due to their potential to produce toxic chemicals and contaminate natural water systems. In June 1999, the St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) initiated a collaborative study in conjunction with the Florida Marine Research Institute, the Florida Department of Health, and Wright State University to determine the geographical distribution of various types of toxin-producing blue-green algae in Florida's surface waters and to positively identify any algal toxins present in these waters. -

Bridge Restrictions

BRIDGE RESTRICTIONS - MARCH 2018 <Double-click here to enter title> 520031 610002 «¬97 «¬89 4 2 ESCAMBIA «¬ 189 29 «¬ 85 «¬ ¤£ «¬ HOLMES SANTA ROSA 187 83 «¬ «¬ 81 610001 87 «¬ «¬ 520076 10 ¬ CRN-2 ¨¦§ 90 79 Pensacola Inset ¤£ «¬ OKALOOSA Pensacola/ «¬285 WALTON «¬77 570055 West Panhandle «¬87 ¦¨§293 WASHINGTON ¤£331 ONLY STATE OWNED «¬83 20 ¤£98 «¬ BRIDGES SHOWN BAY 570091 LEGEND Route with 600108 «¬30 460020 Restricted Bridge(s) 460051 368 Route without 460052 «¬ Restricted Bridge(s) 460112 460113 Non-State Maintained Road 460019 ######Restricted Bridge Number 0 12.5 25 50 Miles ¥ Page 1 of 16 BRIDGE RESTRICTIONS - MARCH 2018 610001 610002 <Double-click here to enter title> 520031 «¬2 HOLMES «¬75 JACKSON 530005 520076 530173 ¬79 CRN-2 « 610004 500092 550144 540042 Central Panhandle ¬77 GADSDEN 27 « ¦¨§10 ¤£ WASHINGTON JEFFERSON 460051 19 460052 470029 ¤£ ONLY STATE OWNED 65 BAY «¬ BRIDGES SHOWN CALHOUN «¬71 ¬267 388 « 231 73 59 LEGEND «¬ ¤£ «¬ LEON «¬ Route with Tallahassee Inset 540069 Restricted Bridge(s) 460020 LIBERTY 368 «¬ Route without 22 WAKULLA «¬ 590014 Restricted Bridge(s) 61 «¬ 30 460112 «¬ Non-State Maintained Road 460113 375 460019 GULF «¬ 540032 T ###### Restricted Bridge Number 380049 490018 «¬377 ¤£98 FRANKLIN «¬30 ¤£319 «¬300 0 12.5 25 50 Miles ¥ Page 2 of 16 BRIDGE RESTRICTIONS - MARCH 2018 350030 <Double-click320017 here to enter title> JEFFERSON «¬145 540042 41 19 ¤£ ¤£ 55 2 «¬ ¬47 «¬ 53 6 HAMILTON «COLUMBIA «¬ «¬ 720026 10 ¦¨§ 290030 59 370015 «¬ 350044 540069 MADISON ¤£441 BAKER 370013 290071 CRN-2 370014 270067