The Causes Behind the Growing Gender Partisan Gap in Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Report Card

Congressional Report Card NOTE FROM BRIAN DIXON Senior Vice President for Media POPULATION CONNECTION and Government Relations ACTION FUND 2120 L St NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20037 ou’ll notice that this year’s (202) 332–2200 Y Congressional Report Card (800) 767–1956 has a new format. We’ve grouped [email protected] legislators together based on their popconnectaction.org scores. In recent years, it became twitter.com/popconnect apparent that nearly everyone in facebook.com/popconnectaction Congress had either a 100 percent instagram.com/popconnectaction record, or a zero. That’s what you’ll popconnectaction.org/116thCongress see here, with a tiny number of U.S. Capitol switchboard: (202) 224-3121 exceptions in each house. Calling this number will allow you to We’ve also included information connect directly to the offices of your about some of the candidates senators and representative. that we’ve endorsed in this COVER CARTOON year’s election. It’s a small sample of the truly impressive people we’re Nick Anderson editorial cartoon used with supporting. You can find the entire list at popconnectaction.org/2020- the permission of Nick Anderson, the endorsements. Washington Post Writers Group, and the Cartoonist Group. All rights reserved. One of the candidates you’ll read about is Joe Biden, whom we endorsed prior to his naming Sen. Kamala Harris his running mate. They say that BOARD OF DIRECTORS the first important decision a president makes is choosing a vice president, Donna Crane (Secretary) and in his choice of Sen. Harris, Joe Biden struck gold. Carol Ann Kell (Treasurer) Robert K. -

Big Business and Conservative Groups Helped Bolster the Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During the Second Fundraising Quarter of 2021

Big Business And Conservative Groups Helped Bolster The Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During The Second Fundraising Quarter Of 2021 Executive Summary During the 2nd Quarter Of 2021, 25 major PACs tied to corporations, right wing Members of Congress and industry trade associations gave over $1.5 million to members of the Congressional Sedition Caucus, the 147 lawmakers who voted to object to certifying the 2020 presidential election. This includes: • $140,000 Given By The American Crystal Sugar Company PAC To Members Of The Caucus. • $120,000 Given By Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s Majority Committee PAC To Members Of The Caucus • $41,000 Given By The Space Exploration Technologies Corp. PAC – the PAC affiliated with Elon Musk’s SpaceX company. Also among the top PACs are Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and the National Association of Realtors. Duke Energy and Boeing are also on this list despite these entity’s public declarations in January aimed at their customers and shareholders that were pausing all donations for a period of time, including those to members that voted against certifying the election. The leaders, companies and trade groups associated with these PACs should have to answer for their support of lawmakers whose votes that fueled the violence and sedition we saw on January 6. The Sedition Caucus Includes The 147 Lawmakers Who Voted To Object To Certifying The 2020 Presidential Election, Including 8 Senators And 139 Representatives. [The New York Times, 01/07/21] July 2021: Top 25 PACs That Contributed To The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million The Top 25 PACs That Contributed To Members Of The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million During The Second Quarter Of 2021. -

2016 Lilly Report of Political Financial Support

16 2016 Lilly Report of Political Financial Support 1 16 2016 Lilly Report of Political Financial Support Lilly employees are dedicated to innovation and the discovery of medicines to help people live longer, healthier and more active lives, and more importantly, doing their work with integrity. LillyPAC was established to work to ensure that this vision is also shared by lawmakers, who make policy decisions that impact our company and the patients we serve. In a new political environment where policies can change with a “tweet,” we must be even more vigilant about supporting those who believe in our story, and our PAC is an effective way to support those who share our views. We also want to ensure that you know the story of LillyPAC. Transparency is an important element of our integrity promise, and so we are pleased to share this 2016 LillyPAC annual report with you. LillyPAC raised $949,267 through the generous, voluntary contributions of 3,682 Lilly employees in 2016. Those contributions allowed LillyPAC to invest in 187 federal candidates and more than 500 state candidates who understand the importance of what we do. You will find a full financial accounting in the following pages, as well as complete lists of candidates and political committees that received LillyPAC support and the permissible corporate contributions made by the company. In addition, this report is a helpful guide to understanding how our PAC operates and makes its contribution decisions. On behalf of the LillyPAC Governing Board, I want to thank everyone who has made the decision to support this vital program. -

Mccourt School Bipartisan Index House Scores 116Th Congress First Session (2019)

The Lugar Center - McCourt School Bipartisan Index House Scores 116th Congress First Session (2019) Representative (by score) Representative (alphabetical) # Name State Party Score # Name State Party Score 1 Brian Fitzpatrick PA R 5.38508 397 Ralph Abraham LA R -0.83206 2 John Katko NY R 3.47273 345 Alma Adams NC D -0.57450 3 Pete King NY R 3.26837 318 Robert Aderholt AL R -0.43685 4 Josh Gottheimer NJ D 2.95943 363 Pete Aguilar CA D -0.67145 5 Don Young AK R 2.70035 436 Rick Allen GA R -1.54771 6 Chris Smith NJ R 2.62428 115 Colin Allred TX D 0.26984 7 Ron Kind WI D 2.39805 336 Justin Amash MI R -0.52046 8 Collin Peterson MN D 2.12892 131 Mark Amodei NV R 0.19731 9 Jenniffer González PR R 1.83721 348 Kelly Armstrong ND R -0.60279 10 David McKinley WV R 1.64501 380 Jodey Arrington TX R -0.72744 11 Steve Stivers OH R 1.51083 106 Cindy Axne IA D 0.30460 12 Lee Zeldin NY R 1.48478 223 Brian Babin TX R -0.10590 13 Rodney Davis IL R 1.42097 31 Don Bacon NE R 1.07937 14 Elise Stefanik NY R 1.40772 155 Jim Baird IN R 0.12198 15 Joe Cunningham SC D 1.39718 82 Troy Balderson OH R 0.47167 16 Abigail Spanberger VA D 1.36993 373 Jim Banks IN R -0.70221 17 Tom Reed NY R 1.28234 392 Andy Barr KY R -0.79377 18 Adam Kinzinger IL R 1.24123 367 Nanette Barragán CA D -0.68341 19 Derek Kilmer WA D 1.23986 295 Karen Bass CA D -0.34686 20 Jeff Van Drew NJ D 1.23527 198 Joyce Beatty OH D -0.03186 21 Tom O'Halleran AZ D 1.17574 226 Ami Bera CA D -0.11738 22 Anthony Brindisi NY D 1.16127 96 Jack Bergman MI R 0.40806 23 Peter Welch VT D 1.15690 270 Don Beyer VA -

CHC Task Force Meeting November 20, 2020 Zoom Help

CHC Task Force Meeting November 20, 2020 Zoom Help You can also send questions through Chat. Send questions to Everyone or a specific person. Everyone will be muted. You can unmute yourself to ask questions by clicking on the microphone or phone button. Agenda • Welcome, Chris Shank, President & CEO, NCCHCA • Election Debrief, Harry Kaplan & Jeff Barnhart, McGuireWoods Consulting • 2021 Policy Priorities, Brendan Riley, Director of Policy, NCCHCA • Experience with Carolina Access, Daphne Betts-Hemby, CFO, Kinston Community Health Center • Updates, Shannon Dowler, MD, NC Division of Health Benefits • Wrap-Up Slides & Other Info will be available on our website: www.ncchca.org/covid-19/covid19-general-information/ Welcome from Chris Shank, President & CEO, NCCHCA North Carolina Election Recap November 18, 2020 McGuireWoods | 5 CONFIDENTIAL THE COUNT McGuireWoods Consulting | 6 CONFIDENTIAL VOTER TURNOUT In North Carolina… ✓ 5,545,859 voters ✓ 75.4% of registered voters cast a ballot ✓4,629,200 of voters voted early ✓ 916,659 voted on Election Day ✓ Voter turnout increased about 6% over 2016 McGuireWoods Consulting | 7 CONFIDENTIAL FEDERAL RACES McGuireWoods Consulting | 8 CONFIDENTIAL FEDERAL RACES ✓ US PRESIDENT President Donald Trump (R) Former Vice President Joe Biden INCUMBENT (D) 2,758,776 (49.93%) 2,684,303 (48.59%) ✓ US SENATE Cal Cunningham (D) Thom Tillis (R) 2,569,972 (46.94%) INCUMBENT 2,665,605(48.69%) McGuireWoods | 9 CONFIDENTIAL FEDERAL RACES US HOUSE Virginia Foxx (R)- INCUMBENT- 66.93% ✓ DISTRICT 9: David Brown (D)- 31.11% -

Entity Name State Election Period House/Senate Result Friends to Elect Dr

Entity Name State Election Period House/Senate Result Friends to Elect Dr. Greg Murphy to Congress NC Run-Off 2020 House Won JEFF COLEMAN FOR CONGRESS, INC. AL Run-Off 2020 House Lost ADRIAN SMITH FOR CONGRESS NE Primary 2020 House Won ANDY BARR FOR CONGRESS, INC. KY Primary 2020 House Won ANDY HARRIS FOR CONGRESS MD Primary 2020 House Won ANGIE CRAIG FOR CONGRESS MN Primary 2020 House Won ANNA ESHOO FOR CONGRESS CA Primary 2020 House Won BARBARA LEE FOR CONGRESS CA Primary 2020 House Won BEATTY FOR CONGRESS OH Primary 2020 House Won BERA FOR CONGRESS CA Primary 2020 House Won BILIRAKIS FOR CONGRESS FL Primary 2020 House Won BRADY FOR CONGRESS TX Primary 2020 House Won BRENDA LAWRENCE FOR CONGRESS MI Primary 2020 House Won BRIAN HIGGINS FOR CONGRESS NY Primary 2020 House Won Brindisi for Congress NY Primary 2020 House Won BUCSHON FOR CONGRESS IN Primary 2020 House Won BUDDY CARTER FOR CONGRESS GA Primary 2020 House Won CASTOR FOR CONGRESS FL Primary 2020 House Won CATHY MCMORRIS RODGERS FOR CONGRESS WA Primary 2020 House Won CITIZENS FOR BOYLE PA Primary 2020 House Won CITIZENS FOR RUSH IL Primary 2020 House Won CLARKE FOR CONGRESS NY Primary 2020 House Won COLE FOR CONGRESS OK Primary 2020 House Won Committee to Elect Steve Watkins KS Primary 2020 House LOST COMMITTEE TO RE-ELECT LINDA SANCHEZ CA Primary 2020 House Won DARREN SOTO FOR CONGRESS FL Primary 2020 House Won DAVID ROUZER FOR CONGRESS NC Primary 2020 House Won DAVID SCOTT FOR CONGRESS GA Primary 2020 House Won DAVIS FOR CONGRESS/FRIENDS OF DAVIS IL Primary 2020 House Won DEBBIE DINGELL FOR CONGRESS MI Primary 2020 House Won DEBBIE WASSERMAN SCHULTZ FOR CONGRESS FL Primary 2020 House Won DELBENE FOR CONGRESS WA Primary 2020 House Won DOGGETT FOR CONGRESS TX Primary 2020 House Won Donna Shalala for Congress FL Primary 2020 House Won DOYLE FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE PA Primary 2020 House Won DR. -

FY 2019 Political Contributions.Xlsx

WalgreenCoPAC Political Contributions: FY 2019 Recipient Amount Arkansas WOMACK FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE 1,000.00 Arizona BRADLEY FOR ARIZONA 2018 200.00 COMMITTE TO ELECT ROBERT MEZA FOR STATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 200.00 ELECT MICHELLE UDALL 200.00 FRIENDS OF WARREN PETERSEN 200.00 GALLEGO FOR ARIZONA 1,000.00 JAY LAWRENCE FOR THE HOUSE 18 200.00 KATE BROPHY MCGEE FOR AZ 200.00 NANCY BARTO FOR HOUSE 2018 200.00 REGINA E. COBB 2018 200.00 SHOPE FOR HOUSE 200.00 VINCE LEACH FOR SENATE 200.00 VOTE HEATHER CARTER SENATE 200.00 VOTE MESNARD 200.00 WENINGER FOR AZ HOUSE 200.00 California AMI BERA FOR CONGRESS 4,000.00 KAREN BASS FOR CONGRESS 3,500.00 KEVIN MCCARTHY FOR CONGRESS 5,000.00 SCOTT PETERS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 TONY CARDENAS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 WALTERS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 Colorado CHRIS KENNEDY BACKPAC 400.00 COFFMAN FOR CONGRESS 2018 1,000.00 CORY GARDNER FOR SENATE 5,000.00 DANEYA ESGAR LEADERSHIP FUND 400.00 STEVE FENBERG LEADERSHIP FUND 400.00 Connecticut LARSON FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 Delaware CARPER FOR SENATE 1,000.00 Florida BILIRAKIS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 DARREN SOTO FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 DONNA SHALALA FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 STEPHANIE MURPHY FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 VERN BUCHANAN FOR CONGRESS 2,500.00 Georgia BUDDY CARTER FOR CONGRESS 4,000.00 Illinois 1 WalgreenCoPAC Political Contributions: FY 2019 Recipient Amount CHUY GARCIA FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 CITIZENS FOR RUSH 1,000.00 DAN LIPINSKI FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 DAVIS FOR CONGRESS/FRIENDS OF DAVIS 1,500.00 FRIENDS OF CHERI BUSTOS 1,000.00 FRIENDS OF DICK DURBIN COMMITTEE -

Read Letter Here

SCOTT STONE Former Member – North Carolina House of Representatives January 8, 2020 Senator Richard Burr Senator Thom Tillis Representative G.K. Butterfield Representative George Holding Representative Richard Hudson Representative Greg Murphy Representative Dan Bishop Representative David Price Representative Patrick McHenry Representative Virginia Foxx Representative Mark Meadows Representative Mark Walker Representative Alma Adams Representative David Rouzer Representative Ted Budd Subject: Federal Action Needed to Require Compliance with ICE Detainers North Carolina Counties with US Marshal IGAs Dear Honorable Members of North Carolina’s Congressional Delegation: North Carolina has seven sheriffs who refuse to honor ICE detainers. Three of these sheriffs’ departments hold Intergovernmental Agreements (IGAs) to serve as federal detention facilities. These contracts are very lucrative as the IGAs generate more than $35.3 million between the three counties. This is a county revenue stream that far exceeds the cost of housing federal inmates. The sheriffs in Cabarrus, Gaston, Henderson, and New Hanover counties have similar IGAs with the U.S. Marshals Office to serve as federal detention facilities, yet those sheriffs willingly cooperate with ICE, as required by their oaths of office. While seven sheriffs claim they have no legal right to honor these detainers and refuse to cooperate with a federal law enforcement agency, the other 93 sheriffs in North Carolina do not appear to share this interpretation. From my travels across the state over the past year as a statewide candidate, it is clear citizens across the state are very concerned about sheriffs refusing to cooperate with ICE. This is not an issue that stops at a county border since defendants can easily move across the state and commit crimes in other counties. -

GUIDE to the 117Th CONGRESS

GUIDE TO THE 117th CONGRESS Table of Contents Health Professionals Serving in the 117th Congress ................................................................ 2 Congressional Schedule ......................................................................................................... 3 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) 2021 Federal Holidays ............................................. 4 Senate Balance of Power ....................................................................................................... 5 Senate Leadership ................................................................................................................. 6 Senate Committee Leadership ............................................................................................... 7 Senate Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................. 8 House Balance of Power ...................................................................................................... 11 House Committee Leadership .............................................................................................. 12 House Leadership ................................................................................................................ 13 House Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................ 14 Caucus Leadership and Membership .................................................................................... 18 New Members of the 117th -

United States Senate

F ORMER S TATE L EGISLATORS IN THE 11 7 TH C ONGRESS as of December 30, 2020 UNITED STATES SENATE Nebraska UNITED STATES HOUSE Connecticut Steve Scalise (R) Grace Meng (D) Tennessee Deb Fischer (R) OF REPRESENTATIVES Joe Courtney (D) Joe Morrelle (D) Tim Burchett (R) 45 Total John Larson (D) Maine Jerrold Nadler (D) Steve Cohen (D) New Hampshire 193 Total Jared Golden (D) Paul Tonko (D) Mark Green (R) 22 Republicans Jeanne Shaheen (D) Florida Chellie Pingree (D) Lee Zeldin (R) Margaret Wood Hassan (D) 95 Democrats Gus Bilirakis (R) Andrew Garbarino (R) Texas Charlie Crist (D) Maryland Kevin Brady (R) 23 Democrats (Includes one Delegate) Nicole Malliotakis (R) New Jersey Ted Deutch (D) Anthony Brown (D) Joaquin Castro (D) Robert Menendez (D) Mario Diaz-Balart (R) Andy Harris (R) Henry Cuellar (D) 96 Republicans Northern Mariana Islands Lois Frankel (D) Steny Hoyer (D) Lloyd Doggett (D) Alabama New York Matt Gaetz (R) Jamie Raskin (D) Gregorio C. Sablan (I) Sylvia Garcia (D) Richard Shelby (R) 1 Independent (Delegate) Charles Schumer (D) Al Lawson (D) Lance Gooden (R) William Posey (R) Massachusetts North Carolina Van Taylor (R) Alaska 1 New Progressive Party Deborah Ross (D) North Carolina (Resident Commissioner from Darren Soto (D) Katherine Clark (D) Marc Veasey (D) Lisa Murkowski (R) Thom Tillis (R) Debbie Wasserman-Schultz (D) Bill Keating (D) Dan Bishop (R) Randy Weber (R) Puerto Rico) Alma Adams (D) Greg Steube (R) Stephen Lynch (D) Pat Fallon (R) Arizona Ohio Daniel Webster (R) Virginia Foxx (R) Patrick McHenry (R) Krysten Sinema -

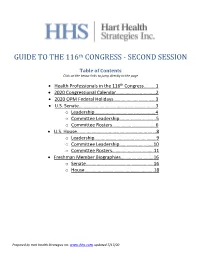

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

2016 POLITICAL DONATIONS Made by WEYERHAEUSER POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE (WPAC)

2016 POLITICAL DONATIONS made by WEYERHAEUSER POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE (WPAC) ALABAMA U.S. Senate Sen. Richard Shelby $2,500 U.S. House Rep. Robert Aderholt $5,000 Rep. Bradley Byrne $1,500 Rep. Elect Gary Palmer $1,000 Rep. Martha Roby $2,000 Rep. Terri Sewell $3,500 ARKANSAS U.S. Senate Sen. John Boozman $2,000 Sen. Tom Cotton $2,000 U.S. House Rep. Elect Bruce Westerman $4,500 FLORIDA U.S. House Rep. Vern Buchanan $2,500 Rep. Ted Yoho $1,000 GEORGIA U.S. Senate Sen. Johnny Isakson $3,000 U.S. House Rep. Rick Allen $1,500 Rep. Sanford Bishop $2,500 Rep. Elect Buddy Carter $2,500 Rep. Tom Graves $2,000 Rep. Tom Price $2,500 Rep. Austin Scott $1,500 IDAHO U.S. Senate Sen. Mike Crapo $2,500 LOUISIANA U.S. Senate Sen. Bill Cassidy $1,500 U.S. House Rep. Ralph Abraham $5,000 Rep. Charles Boustany $5,000 Rep. Garret Graves $1,000 Rep. John Kennedy $2,500 Rep. Stephen Scalise $3,000 MAINE U.S. Senate Sen. Susan Collins $1,500 Sen. Angus King $2,500 U.S. House Rep. Bruce Poliquin $2,500 MICHIGAN U.S. Senate Sen. Gary Peters $1,500 Sen. Debbie Stabenow $2,000 MINNESOTA U.S. Senate Sen. Amy Klobuchar $2,000 U.S. House Rep. Rick Nolan $1,000 Rep. Erik Paulsen $1,000 Rep. Collin Peterson $1,500 MISSISSIPPI U.S. Senate Sen. Roger Wicker $4,000 U.S. House Rep. Gregg Harper $4,000 Rep. Trent Kelly $3,000 Rep.