Sustainable Transportation in Keene and the Monadnock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Car Sharing Market In

CarSharing: State of the Market and Growth Potential By Chris Brown, March/April 2015 - Also by this author Though aspects of carsharing have existed since 1948 in Switzerland, it was only in the last 15 years that the concept has evolved into a mobility solution in the United States. Photo by Chris Brown. In that time, the carsharing market has grown from a largely subsidized, university research-driven experiment into a full-fledged for-profit enterprise, owned primarily by traditional car rental companies and auto manufacturers. Today, Zipcar (owned by Avis Budget Group), car2go (owned by Daimler), Enterprise CarShare and Hertz 24/7 control about 95% of the carsharing market in the U.S. Compared to car rental, total fleet size and revenues for carsharing remain relatively small. The “Fall 2014 Carsharing Outlook,” produced by the Transportation Sustainability Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley, reports 19,115 carsharing cars in the U.S., shared by about 996,000 members. Total annual revenue for carsharing in the U.S. is about $400 million, compared to the $24 billion in revenue for the traditional car rental market. Those carshare numbers have roughly doubled in five or six years, demonstrating steady growth but not an explosion. Yet technology, new transportation models, shifting demographics and changing attitudes on mobility present new opportunities. Is carsharing poised to take advantage? Market Drivers As carsharing in the U.S. is essentially consolidated under those four market leaders, they will inevitably be the drivers of much of that growth. Market watchers see one-way — or point-to-point carsharing — as a growth accelerator. -

Carsharing's Impact and Future

Carsharing's Impact and Future Advances in Transport Policy and Planning Volume 4, 2019, Pages 87-120 October 23, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.atpp.2019.09.002 Susan Shaheen, PhD Adam Cohen Emily Farrar 1 Carsharing's Impact and Future Authors: Susan Shaheen, PhDa [email protected] Adam Cohenb [email protected] Emily Farrarb [email protected] Affiliations: aCivil and Environmental Engineering and Transportation Sustainability Research Center University of California, Berkeley 408 McLaughlin Hall Berkeley, CA 94704 bTransportation Sustainability Research Center University of California, Berkeley 2150 Allston Way #280 Berkeley, CA 94704 Corresponding Author: Susan Shaheen, PhD [email protected] 2 Carsharing’s Impact and Future ABSTRACT Carsharing provides members access to a fleet of autos for short-term use throughout the day, reducing the need for one or more personal vehicles. This chapter reviews key terms and definitions for carsharing, common carsharing business models, and existing impact studies. Next, the chapter discusses the commodification and aggregation of mobility services and the role of Mobility on Demand (MOD) and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) on carsharing. Finally, the chapter concludes with a discussion of how the convergence of electrification and automation is changing carsharing, leading to shared automated and electric vehicle (SAEV) fleets. Keywords: Carsharing, Shared mobility, Mobility on Demand (MOD), Mobility as a Service (MaaS), Shared automated electric vehicles (SAEVs) 1 INTRODUCTION Across the globe, innovative and emerging mobility services are offering residents, businesses, travelers, and other users more options for on-demand mobility. In recent years, carsharing has grown rapidly due to changing perspectives toward transportation, car ownership, business and institutional fleet ownership, and urban lifestyles. -

The Innovative Transportation Index the Cities Where New Technologies and Tools Can Reduce Your Need to Own a Car

The Innovative Ridesourcing One-way Ridesharing carsharing Transportation Round-trip Peer-to-peer Real-time carsharing carsharing tracking Index Bikesharing Online Multi-modal apps timetables The Cities Where New Technologies Taxi hailing Virtual ticketing and Tools Can Reduce Your Need to Own a Car Education Fund The Innovative Transportation Index The Cities Where New Technologies and Tools Can Reduce Your Need to Own a Car Education Fund Written by: Lindsey Hallock and Jeff Inglis, Frontier Group February 2015 Acknowledgments The authors thank Tom Fairchild and Michael Schade of Mobility Lab; Larry Filler of LF Consulting; Deron Lovaas and Fernando Cazares of the Natural Resources De- fense Council’s Urban Solutions Program; Bibiana McHugh of TriMet; Robert Puentes of the Brookings Institution; Susan Shaheen and Adam Cohen of the Transportation Sustainability Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley; Alan Woodland of the CarSharing Association; and Susan Zielinski of Sustainable Mobility and Acces- sibility Research and Transformation (SMART) at the University of Michigan for their helpful review of this document. Thanks to Sharon Feigon of the Shared-Use Mobility Center for her contribution to this report. Additional thanks to Phineas Baxandall of U.S. PIRG Education Fund and Tony Dutzik and Tom Van Heeke of Frontier Group for editorial assistance. The authors bear responsibility for any factual errors. The recommendations are those of Frontier Group and Arizona PIRG Education Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or those who provided review. 2015 Frontier Group. Some Rights Reserved. -

Planning for Shared Mobility

UC Berkeley Recent Work Title Planning for Shared Mobility Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0dk3h89p ISBN 9781611901863 Authors Cohen, Adam Shaheen, Susan, PhD Publication Date 2018-03-01 DOI 10.7922/G2NV9GDD eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PAS REPORTPAS 583 P LANNING FOR SHARED MOBILITY American Planning Association 205 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 1200 Chicago, IL 60601-5927 planning.org | Cohen and Shaheen and Cohen PAS REPORT 5 8 3 A MERICAN PLANNING ASSOCIATION PLANNING FOR SHARED MOBILITY Adam Cohen and Susan Shaheen POWER TOOLS ABOUT THE AUTHORS APA RESEARCH MISSION Adam Cohen is a shared mobility researcher at the Transporta- tion Sustainability Research Center at the University of California, APA conducts applied, policy-relevant research Berkeley. Since joining the group in 2004, his research has focused that advances the state of the art in planning on shared mobility and emerging technologies. He has coauthored practice. APA’s National Centers for Plan- numerous articles and reports on shared mobility in peer-reviewed ning—the Green Community Research Center, journals and conference proceedings. His academic background is the Hazards Planning Research Center, and the in city and regional planning and international affairs. Planning and Community Health Research PAS SUBSCRIBERS GET EVERY NEW PAS REPORT, PLUS Center—guide and advance a research direc- Susan Shaheen is an adjunct professor in the Department of Civil THESE RESOURCES FOR EVERYONE IN THE OFFICE TO SHARE tive that addresses important societal issues. and Environmental Engineering and a research engineer with the APA’s research, education, and advocacy pro- Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, grams help planners create communities of Berkeley. -

Carsharing Models, Impacts + Latest Understanding

CARSHARING MODELS, IMPACTS + LATEST UNDERSTANDING Susan A. Shaheen, Ph.D. Adjunct Professor, Civil & Environmental Engineering and Co-Director, TSRC University of California, Berkeley OVERVIEW . Carsharing service models . Impacts . Roundtrip . Business . P2P . One-way . Carsharing highlights: 2015 . Acknowledgements Roundtrip Carsharing: Round trip, pay by the hour/mile, non- profit and for profit fleet models Peer-to-Peer Carsharing: Shared use of private vehicle typically managed by third party One-Way Carsharing: Pay by the minute, point to point, fleet operated, street parking agreements Fractional Ownership Carsharing: Individuals sublease or subscribe to a © UC Berkeley, 2015 vehicle owned by a third party Carsharing There are many flavors of carsharing NORTH AMERICAN LONGITUDINAL TRENDS 1,800,000 30,000 1,600,000 25,000 1,400,000 1,200,000 20,000 1,000,000 15,000 800,000 Vehicles Members 600,000 10,000 400,000 5,000 200,000 0 0 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 Members 117,656 318,898 516,100 908,584 1,625,652 Vehicles 3,337 7,505 10,420 15,795 24,210 Shaheen and Cohen, 2015 © UC Berkeley, 2015 GROWTH OF WORLDWIDE CARSHARING 6,000,000 120,000 5,000,000 100,000 4,000,000 80,000 3,000,000 60,000 Vehicles Members 2,000,000 40,000 1,000,000 20,000 0 0 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 Members 346,610 670,822 1,163,405 1,788,027 4,828,616 Vehicles 11,501 19,403 31,967 43,554 103,980 Shaheen and Cohen, 2015 © UC Berkeley, 2015 2008 N. -

Autodelen Van Niche Naar Mainstream

autodelen van niche naar mainstream Een buurt vol autodelers een studie naar de toekomst van autodelen in Vlaanderen 2 Stel je voor. Het is 2030. Je hebt geen auto voor de deur, maar je geraakt toch vlot waar je Autodelen, vandaag en morgen I 5 moet zijn. Niet alleen met fiets of met het openbaar vervoer, maar ook met de de deelwa- gen. En niet alleen jij doet dit, ook je buren, vrienden, familie en kennissen. Onmogelijk zeg je? 1. Autodelen in al zijn vormen I 6 Internationale voorspellingen voorzien dat tegen 2030 één op de tien wagens gedeeld zul- 1.1. Geschiedenis van autodelen 6 len worden. Tegen 2050 zelfs één op de drie wagens. In stedelijke gebieden zullen er veel I meer deelwagens zijn, in landelijke gebieden minder. Internationaal I 6 Met deze studie geven we je inzicht in hoe autodelen er in de toekomst in Vlaanderen kan In Vlaanderen I 7 uitzien. Wat is autodelen precies? Wie zijn de belangrijkste en toekomstige aanbieders? Wie wil een deelwagen gebruiken? Zal autodelen in Vlaanderen doorbreken? Welke zijn de rem- Wat is Autodelen.net? I 7 men en de stimuli? Wat voor impact zal dit hebben op ons dagelijks leven? Tot slot geven 1.2 Definitie van autodelen en autodeelsysteem I 8 we enkele aanbevelingen aan overheden op verschillende niveaus om op deze transitie in te spelen. Naar een duidelijke definitie I 8 Carsharing is geen Uber of ridesharing I 9 1.3 Indeling van autodeelsystemen I 11 Business-to-consumer-carsharing (B2C) I 11 Peer-to-peer-carsharing (P2P) I 14 Not-for-profit- of co-op-carsharing (NFP) I 14 2. -

Dynamic Ride-Share, Car-Share, and Bike-Share and State-Level Mobility

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA/TX-15/0-6818-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date DYNAMIC RIDE-SHARE, CAR-SHARE, AND BIKE-SHARE AND Published: February 2016 STATE–LEVEL MOBILITY: RESEARCH TO SUPPORT 6. Performing Organization Code ASSESSING, ATTRACTING, AND MANAGING SHARED MOBILITY PROGRAMS - FINAL REPORT 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Kristi Miller, Tina Geiselbrecht, Maarit Moran, and M.A. Miller Report 0-6818-1 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Texas A&M Transportation Institute College Station, Texas 77843-3135 11. Contract or Grant No. Project 0-6818 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Texas Department of Transportation Technical Report: Research and Technology Implementation Office September 2014–December 2015 125 E. 11th Street 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Austin, Texas 78701-2483 15. Supplementary Notes Project performed in cooperation with the Texas Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration. Project Title: Dynamic Ride-Sharing, Bike-Sharing, Car-Sharing, and State-Level Mobility URL: http://tti.tamu.edu/documents/0-6818-1.pdf 16. Abstract Texas is one of the fastest growing states in the nation, and its growth is expected to continue, supported by diversity in its economy, geography, and population. The challenge of prioritizing limited resources in this environment requires a proactive approach to travel demand management. This project provides guidance for TxDOT in its planning and mobility efforts and in understanding the viability of various alternative mobility programs. -

CARSHARING: an ALTERNATIVE to PRIVATE VEHICLE OWNERSHIP Background, Case Studies, and Recommended Next Steps for the Monadnock Region

CARSHARING: AN ALTERNATIVE TO PRIVATE VEHICLE OWNERSHIP Background, Case Studies, and Recommended Next Steps for the Monadnock Region Prepared for the Monadnock Alliance for Sustainable Transportation (MAST) by Southwest Region Planning Commission (SWRPC) Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the Southwest Region Planning Commission with assistance from Lisa Donnelly, Keene State College intern. The report was initiated by the Monadnock Alliance for Sustainable Transportation (MAST). The MAST Steering Committee provided valuable input they throughout the development of this report. In addition, the following individuals contributed to this report through telephone and email interviews: Annie Bourdon, Executive Director, CarShare Vermont Tony Duncan, Brattleboro Time Share Wayne Feiden, Director of Planning and Sustainability, City of Northampton Emily Fleck, Executive Director, Carsharing Association Bruce Gardave, Executive Director, Kootenay Carshare Cooperative Cary Gaunt, Director of Campus Sustainability, Keene State College Emma Kerr, Sustainability Coordinator, Smith College John Kondos, President, Monadnock Sustainability Network The preparation of this document has been supported by the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the State Planning and Research Program, Section of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. About the Monadnock Alliance for Sustainable Transportation MAST is an alliance of individuals and organizations working to implement sustainable transportation solutions for the Monadnock Region. MAST recognizes the broad impacts that our transportation system has on us as individuals and as communities - everything from access to employment and services to cost of living to our health and beyond. -

Swutc/12/476660-00079-1 Free

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. SWUTC/12/476660-00079-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date FREE-FLOATING CARSHARING SYSTEMS: August 2012 INNOVATIONS IN MEMBERSHIP PREDICTION, MODE 6. Performing Organization Code SHARE, AND VEHICLE ALLOCATION OPTIMIZATION METHODOLOGIES 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Katherine Kortum, Randy Machemehl 476660-00079-1 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Center for Transportation Research University of Texas at Austin 11. Contract or Grant No. 1616 Guadalupe Street, Suite 4.200 DTRT07-G-0006 Austin, Texas 78701 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Southwest Region University Transportation Center Texas A&M Transportation Institute Texas A&M University System 14. Sponsoring Agency Code College Station, Texas 77843-3135 15. Supplementary Notes Supported by revenues from the US Department of Transportation. 16. Abstract Free-floating carsharing systems are among the newest types of carsharing programs. They allow one-way rentals and have no set “homes” or docks for the carsharing vehicles; instead, users are permitted to drive the vehicles anywhere within the operating zone and leave the vehicle in a legal parking space. Compared to traditional carsharing operations, free-floating carsharing allows much greater spontaneity and flexibility for the user. However, it leads to additional operational challenges for the program. This report provides methodologies for some of these challenges facing both free-floating and traditional carsharing programs. First, it analyzes cities with carsharing to determine what characteristics increase the likelihood of the city supporting a successful carsharing program; high overall population, small household sizes, high transit use, and high levels of government employment all make the city a likely carsharing contender. -

Personal Vehicle Sharing Services in North America Research in Transportation Business & Management, Volume 3, Pages 71-81 August 2012

Personal Vehicle Sharing Services in North America Research in Transportation Business & Management, Volume 3, Pages 71-81 August 2012 Susan Shaheen Mark A. Mallery Karla J. Kingsley PERSONAL VEHICLE SHARING SERVICES IN NORTH AMERICA Abstract Over the past three decades, carsharing has grown from a collection of local grassroots organizations into a worldwide industry. Traditional carsharing, though expanding, has a limited network of vehicles and locations. The next generation of shared-use vehicle services could overcome such expansion barriers as capital costs and land use by incorporating new concepts like personal vehicle sharing. Personal vehicle sharing provides short-term access to privately-owned vehicles. As of May 2012, there were 33 personal vehicle sharing operators worldwide, with 10 active or in pilot phase, three planned, and four defunct in North America. Due to operator non-disclosure, personal vehicle sharing member numbers are currently unknown. The authors investigated personal vehicle sharing in North America by conducting 34 expert interviews. This research explores the development of personal vehicle sharing including business models, market opportunities, and service barriers to assess its early viability as a sustainable transportation mode and to provide a foundation for future research on the topic. Personal vehicle sharing has the potential to impact the transportation sector by increasing the availability and interconnectivity among modes and providing greater alternatives to vehicle ownership in more geographic locations. Keywords: Personal vehicle sharing, carsharing, peer-to-peer (P2P) carsharing, fractional ownership, collaborative consumption, market adoption Introduction Although the personal automobile remains the primary transportation mode in North America, recent research supports the view that private vehicle use is in decline in numerous countries (Millard-Ball and Schipper, 2011; Newman and Kenworthy, 2011). -

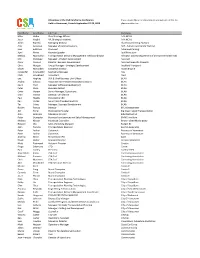

Attendees at the CSA Carsharing Conference If You Would Like an Inroduction to Any Person on This List Held in Vancouver, Canada

Attendees at the CSA Carsharing Conference If you would like an inroduction to any person on this list Held in Vancouver, Canada September 22-23, 2015 please contact us First Name Last Name Job Title Company Mike Hetke Chief Strategy Officer AAA NCNU Jason Haight VP, Strategic Initiatives AAA NCNU Julian Espiritu Managing Director Abrams Carsharing Advisors Amy Severson Manager of Communications ACT - Autism Community Training Jons Edstrand President Advanced Parking April Rinne Keynote Speaker AprilRinne.com Melissa MacMahon Transportation Demand Management Field Coordinator Arlington County Department of Environmental Services Erik Dempsey Manager - Product Development Assurant Oscar Quijano Director, Business Development Assurant Specialty Property Chris Morgan Group Manager - Strategic Development Auckland Transport Elliott McFadden Executive Director Austin B-cycle Ingigerður Einarsdóttir Marketing Manager Avis Clark Woodland Consultant AWA Eric Hopkins SVP & Chief Business Unit Officer BCAA Andrej Lukovic Associate Vice President Business Solutions BCAA Kevin Poon Manager Software Development BCAA Peter Khoo Business Analyst BCAA Omar Visram Senior Manager, Operations BCAA Shan Parmar Director, Car Sharing BCAA Paul Healey President & CEO BCAA Ken Ontko Senior Vice President and CIO BCAA Tai Silvey Manager, Business Development BCAA Robert Farrow Director BFC Management JM Toriel President & Founder Big Green Island Transportation Arne Lindelien Managing director Bilkollektivet SA Peter Dempster Business Development and Sales Management -

Twenty Years of Car Sharing: a Case Study on the City of Vancouver’S Role in the Growth of Car Sharing in Vancouver

Twenty Years of Car Sharing: A case study on the City of Vancouver’s role in the growth of car sharing in Vancouver By Mitchell Shaw B.A. (International Studies), Simon Fraser University, 2012 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Urban Studies in the Urban Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Mitchell Shaw 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Mitchell Shaw Degree: Master of Urban Studies Title: Twenty Years of Car Sharing: A case study on the City of Vancouver’s role in the growth of car sharing in Vancouver Examining Committee: Chair: Peter V. Hall Professor of Urban Studies and Geography Anthony Perl Senior Supervisor Professor of Urban Studies and Political Science Patrick J. Smith Supervisor Professor of Urban Studies and Political Science Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly External Examiner Professor of Public Policy and Jean Monnet Chair in Innovative Governance University of Victoria Date Defended: May 23, 2018 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This thesis explores the City of Vancouver’s role in supporting the growth of car sharing in Vancouver from 1997 to 2016. In December 2016, Vancouver had the highest number of car share members and vehicles in a single city across North America. Using a mixed methods approach, City documents and interviews are used to assess the impact that City policies have had on the development of this mobility service.