One-Photon Vs. Two-Photon Processes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROTATIONAL SPECTRA (Microwave Spectroscopy)

UNIT-1 ROTATIONAL SPECTRA (Microwave Spectroscopy) Lesson Structure 1.0 Objective 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Classification of molecules 1.3 Rotational spectra of regid diatomic molecules 1.4 Selection rules 1.5 Non-rigid rotator 1.6 Spectrum of a non-rigid rotator 1.7 Linear polyatomic molecules 1.8 Non-linear polyatomic molecules 1.9 Asymmetric top molecles 1.10. Starck effect Solved Problems Model Questions References 1.0 OBJECIVES After studyng this unit, you should be able to • Define the monent of inertia • Discuss the rotational spectra of rigid linear diatomic molecule • Spectrum of non-rigid rotator • Moment of inertia of linear polyatomic molecules Rotational Spectra (Microwave Spectroscopy) • Explain the effect of isotopic substitution and non-rigidity on the rotational spectra of a molecule. • Classify various molecules according to thier values of moment of inertia • Know the selection rule for a rigid diatomic molecule. 1.0 INTRODUCTION Spectroscopy in the microwave region is concerned with the study of pure rotational motion of molecules. The condition for a molecule to be microwave active is that the molecule must possess a permanent dipole moment, for example, HCl, CO etc. The rotating dipole then generates an electric field which may interact with the electrical component of the microwave radiation. Rotational spectra are obtained when the energy absorbed by the molecule is so low that it can cause transition only from one rotational level to another within the same vibrational level. Microwave spectroscopy is a useful technique and gives the values of molecular parameters such as bond lengths, dipole moments and nuclear spins etc. -

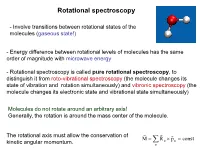

Rotational Spectroscopy

Rotational spectroscopy - Involve transitions between rotational states of the molecules (gaseous state!) - Energy difference between rotational levels of molecules has the same order of magnitude with microwave energy - Rotational spectroscopy is called pure rotational spectroscopy, to distinguish it from roto-vibrational spectroscopy (the molecule changes its state of vibration and rotation simultaneously) and vibronic spectroscopy (the molecule changes its electronic state and vibrational state simultaneously) Molecules do not rotate around an arbitrary axis! Generally, the rotation is around the mass center of the molecule. The rotational axis must allow the conservation of M R α pα const kinetic angular momentum. α Rotational spectroscopy Rotation of diatomic molecule - Classical description Diatomic molecule = a system formed by 2 different masses linked together with a rigid connector (rigid rotor = the bond length is assumed to be fixed!). The system rotation around the mass center is equivalent with the rotation of a particle with the mass μ (reduced mass) around the center of mass. 2 2 2 2 m1m2 2 The moment of inertia: I miri m1r1 m2r2 R R i m1 m2 Moment of inertia (I) is the rotational equivalent of mass (m). Angular velocity () is the equivalent of linear velocity (v). Er → rotational kinetic energy L = I → angular momentum mv 2 p2 Iω2 L2 E E c 2 2m r 2 2I Quantum rotation: The diatomic rigid rotor The rigid rotor represents the quantum mechanical “particle on a sphere” problem: Rotational energy is purely -

Molecular Energy Levels

MOLECULAR ENERGY LEVELS DR IMRANA ASHRAF OUTLINE q MOLECULE q MOLECULAR ORBITAL THEORY q MOLECULAR TRANSITIONS q INTERACTION OF RADIATION WITH MATTER q TYPES OF MOLECULAR ENERGY LEVELS q MOLECULE q In nature there exist 92 different elements that correspond to stable atoms. q These atoms can form larger entities- called molecules. q The number of atoms in a molecule vary from two - as in N2 - to many thousand as in DNA, protiens etc. q Molecules form when the total energy of the electrons is lower in the molecule than in individual atoms. q The reason comes from the Aufbau principle - to put electrons into the lowest energy configuration in atoms. q The same principle goes for molecules. q MOLECULE q Properties of molecules depend on: § The specific kind of atoms they are composed of. § The spatial structure of the molecules - the way in which the atoms are arranged within the molecule. § The binding energy of atoms or atomic groups in the molecule. TYPES OF MOLECULES q MONOATOMIC MOLECULES § The elements that do not have tendency to form molecules. § Elements which are stable single atom molecules are the noble gases : helium, neon, argon, krypton, xenon and radon. q DIATOMIC MOLECULES § Diatomic molecules are composed of only two atoms - of the same or different elements. § Examples: hydrogen (H2), oxygen (O2), carbon monoxide (CO), nitric oxide (NO) q POLYATOMIC MOLECULES § Polyatomic molecules consist of a stable system comprising three or more atoms. TYPES OF MOLECULES q Empirical, Molecular And Structural Formulas q Empirical formula: Indicates the simplest whole number ratio of all the atoms in a molecule. -

6 Basics of Optical Spectroscopy

Chapter 6, page 1 6 Basics of Optical Spectroscopy It is possible, with optical methods, to examine the rotational spectra of small molecules, all the Raman rotational spectra, the vibration spectra including the Raman spectra, and the electron spectra of the bonding electrons. Some of the quantum mechanical foundations of optical spectroscopy were already covered in chapter 3, and the optical methods will be the topic of chapter 7. This chapter is concerned with the relation between the structure of a substance to its rotational, and vibration spectra, and electron spectra of the bonding electrons. A few exceptions are made at the beginning of the chapter. Since the rotational spectrum of large molecules are examined using frequency variable microwave technology, this technology will be briefly explained. 6.1 Rotational Spectroscopy 6.1.1 Microwave Measurement Method Absorption measurements of the rotational transitions necessitates the existence of a permanent dipole moment. Molecules that have no permanent dipole moment, but rather an anisotropic polarizability perpendicular to the axis of rotation, can be measured with Raman scattering. Although rotational spectra of small molecules, e.g. HI, can be examined by optical methods in the distant infrared, the frequency of the rotational transitions is shifted to the range of HF spectroscopy in molecules with large moments of inertia. For this reason, rotational spectroscopy is often called microwave spectroscopy. For the production of microwaves, we could use electron time-of-flight tubes. The reflex klystron is only tunable over a small frequency range. The carcinotron (reverse wave tubes) is tunable over a larger range by variation of the accelerating voltage of the electron beam. -

The Rotational-Vibrational Spectrum of Hcl

The Rotational-Vibrational Spectrum of HCl Objective To obtain the rotationally resolved vibrational absorption spectrum of HCI; to determine the rotational constant and rotational-vibrational coupling constant; to compare the rotational transition intensities with theoretical predictions. NOTE: Bring your textbook to the laboratory. Chapter 13 in McQuarrie is a good reference for this lab. Introduction In this experiment you will examine the energetics of vibrational and rotational motion in the diatomic molecule HCl. The experiment involves detecting transitions between different molecular vibrational and rotational levels brought about by the absorption of quanta of electromagnetic radiation (photons) in the infrared region of the spectrum. The introductory discussion consists of three parts: (1) vibrational and rotational motion and energy quantization, (2) the influence of molecular rotation on vibrational energy levels (and vice versa), and (3) the intensities of rotational transitions. Vibrational Motion Consider how the potential energy of a diatomic molecule AB changes as a function of internuclear distance. For small displacements from equilibrium (typically the case for molecules at room temperature), a simple approximate way of expressing this mathematically is V(x) =1/2 kx2, (1) where the coordinate x represents the change in internuclear separation relative to the equilibrium position; thus, x = 0 represents the equilibrium configuration (i.e., the position with the lowest potential energy). For x < 0 the two atoms are closer to each other, and for x > 0 the two atoms are farther apart. The constant k is called the force constant and its value reflects the strength of the force holding the two masses to each other. -

Quantum Mechanics of Rotational Motion

Chapter 17 Quantum Mechanics of Rotational Motion P. J. Grandinetti Chem. 4300 Would be useful to review Chapter 4 on Classical Rotational Motion. P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 17: Quantum Mechanics of Rotational Motion Rotational Angular Momentum Operators P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 17: Quantum Mechanics of Rotational Motion Rotational Angular Momentum of a System of Particles ⃗ System of particles: Ltotal divided into orbital and spin contributions ⃗ ⃗ ⃗ Ltotal = Lorbital + Lspin ⃗ ⃗ Imagine earth orbiting sun at origin with Lorbital and spinning about its center of mass with Lspin. For molecules, relabel contributions as translational and rotational ⃗ ⃗ ⃗ ; Ltotal = Ltrans + Jrot Í ⃗ Ltrans is associated with center of mass of rigid body translating relative to some fixed origin, Í ⃗ Jrot is associated with rigid body rotating about its center of mass. ⃗ ⃗ With no external torques, to good approximation, Ltrans and Jrot contributions are separately conserved. Approximate molecule as rigid body, and describe motion with Í 3 translational coordinates to follow center of mass Í 3 rotational coordinates to follow orientation of its moment of inertia tensor PAS, , i.e., Euler angles, 휙, 휃, and 휒 P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 17: Quantum Mechanics of Rotational Motion Rotational Angular Momentum Operators in the Body-Fixed Frame Angular momentum vector components for rigid body about center of mass, J⃗, are given in terms of a space-fixed frame and a body-fixed frame. ̂ ̂ ̂ ⃗ Ja, Jb, and Jc represent J components in body-fixed frame, i.e., PAS. Body-fixed frame components are given by 0 1 ) ) ) ̂ ` 휙 휙 휃 휙 휃 Ja = i * sin )휃 * cos cot )휙 + cos csc )휒 0 1 ) ) ) ̂ ` 휙 휙 휃 휙 휃 Jb = i cos )휃 * sin cot )휙 + sin csc )휒 ) ̂ ` Jc = i )휙 P. -

Lecture 18 Long Wavelength Spectroscopy

Lecture 18 Long Wavelength Spectroscopy 1. Introduction 2. The Carriers of the Spectra 3. Molecular Structure 4. Emission and Absorption References • Herzberg, Molecular Spectra & Molecular Structure (c. 1950, 3 volumes) • Herzberg, The Spectra & Structure of Simple Free Radicals, (Cornell, 1971), esp. Parts I & II • Townes & Schawlow, "Microwave Spectroscopy" (Dover 1975) • Astro texts: Lightman & Rybicki, Ch. 10 Shu I, Chs. 28-30 Dopita & Sutherland, Ch. 1 Palla & Stahler, Ch. 5 1. Introduction to Long Wavelength Spectroscopy This course has so far dealt mainly with warm diffuse gas. Perhaps it was fitting that the very last discussion of the warm and very diffuse IGM ended with the question of how the first molecules formed and how molecular hydrogen cooled the cosmic gas enough to form the first stars. The argument has been made that the theory of primordial star formation is simpler than recent star formation because of the absence of dust and magnetic fields. But this misses the important point that theory by itself is nothing without tests and guidance from observations. We therefore switch our focus to the nearby clouds that are now making stars in nearby galaxies (the main topic of the second half of the course) and the central role of long wavelength astronomy. Signatures of the Cool ISM Recall that much of Lecture 1 introduced long wavelength observations of the ISM and noted the primary roles of dust and molecules. COBE 0.1-4 mm spectrum Major IR Space of the Galactic plane. Observatories IRAS 1983 COBE 1991 ISO 1996 SPITZER 2003 Why doesn’t the COBE spectrum show molecular features? Molecular Emission Unlike atoms, molecules can produce many long-wavelength vibrational & rotational transitions by virtue of having (extra degrees of freedom from) more than one nucleus. -

9.5 Rotation and Vibration of Diatomic Molecules

9.5. Rotation and Vibration of Diatomic Molecules 349 9.5 Rotation and Vibration of Diatomic Molecules Up to now we have discussed the electronic states of ri- gid molecules, where the nuclei are clamped to a fixed position. In this section we will improve our model of molecules and include the rotation and vibration of dia- tomic molecules. This means, that we have to take into account the kinetic energy of the nuclei in the Schrö- dinger equation Hψ Eψ, which has been omitted in ˆ the foregoing sections=. We then obtain the Hamiltonian 2 2 1 2 N H ! 2 ! 2 ˆ = − 2 M ∇k − 2m ∇i k 1 k e i 1 != != 2 e Z1 Z2 1 1 1 el Fig. 9.41. Energy En (R) of the rigid molecule and total + 4πε R + r − r + r energy E of the nonrigid vibrating and rotating molecule 0 i, j i, j i i1 i2 ! ! $ % Enucl Eel E0 T H (9.73) ˆkin kin pot ˆk ˆ0 = + + = + can be written as the product of the molecular wave where the first term represents the kinetic energy of the function χ(Rk) (which depends on the positions Rk of nuclei, the second term that of the electrons, the third the nuclei), and the electronic wave function Φ(ri , Rk) represents the potential energy of nuclear repulsion, the of the rigid molecule at arbitrary but fixed nuclear po- fourth that of the electron repulsion and the last term sitions Rk, where the electron coordinates ri are the the attraction between the electrons and the nuclei. -

![Arxiv:1911.12808V1 [Physics.Atom-Ph] 28 Nov 2019 final State Non-Destructively, Leaving the Molecule Ready for Further Manipulation](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9653/arxiv-1911-12808v1-physics-atom-ph-28-nov-2019-nal-state-non-destructively-leaving-the-molecule-ready-for-further-manipulation-4329653.webp)

Arxiv:1911.12808V1 [Physics.Atom-Ph] 28 Nov 2019 final State Non-Destructively, Leaving the Molecule Ready for Further Manipulation

Precision frequency-comb terahertz spectroscopy on pure quantum states of a single molecular ion C. W. Chou1, A. L. Collopy1, C. Kurz1, Y. Lin2;1;3;4, M. E. Harding5, P. N. Plessow6, T. Fortier1;7, S. Diddams1;7, D. Leibfried1;7, and D. R. Leibrandt1;7 1Time and Frequency Division, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Boulder, Colorado 80305, USA 2CAS Key Laboratory of Microscale Magnetic Resonance and Department of Modern Physics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China 3Hefei National Laboratory for Physical Sciences at the Microscale, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China 4Synergetic Innovation Center of Quantum Information and Quantum Physics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China 5Institute of Nanotechnology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany 6Institute of Catalysis Research and Technology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany and 7University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA (Dated: December 2, 2019) Abstract Spectroscopy is a powerful tool for studying molecules and is commonly performed on large thermal molecular ensembles that are perturbed by motional shifts and interactions with the en- vironment and one another, resulting in convoluted spectra and limited resolution. Here, we use generally applicable quantum-logic techniques to prepare a trapped molecular ion in a single quan- tum state, drive terahertz rotational transitions with an optical frequency comb, and read out the arXiv:1911.12808v1 [physics.atom-ph] 28 Nov 2019 final state non-destructively, leaving the molecule ready for further manipulation. We resolve rota- 40 + tional transitions to 11 significant digits and derive the rotational constant of CaH to be BR = 142 501 777.9(1.7) kHz. -

Two-Photon Vibrational Transitions in O As Probes of Variation of the Proton-To-Electron Mass Ratio

atoms Article 16 + Two-Photon Vibrational Transitions in O2 as Probes of Variation of the Proton-to-Electron Mass Ratio Ryan Carollo , Alexander Frenett and David Hanneke * Physics & Astronomy Department, Amherst College, Amherst, MA 01002, USA; [email protected] (R.C.); [email protected] (A.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-413-542-5525 Received: 31 October 2018; Accepted: 18 December 2018; Published: 20 December 2018 Abstract: Vibrational overtones in deeply-bound molecules are sensitive probes for variation of the proton-to-electron mass ratio m. In nonpolar molecules, these overtones may be driven as two-photon 16 + transitions. Here, we present procedures for experiments with O2 , including state-preparation through photoionization, a two-photon probe, and detection. We calculate transition dipole moments 2 2 between all X Pg vibrational levels and those of the A Pu excited electronic state. Using these dipole moments, we calculate two-photon transition rates and AC-Stark-shift systematics for the overtones. We estimate other systematic effects and statistical precision. Two-photon vibrational 16 + transitions in O2 provide multiple routes to improved searches for m variation. Keywords: precision measurements; fundamental constants; variation of constants; proton-to-electron mass ratio; molecular ions; forbidden transition; two-photon transition; vibrational overtone 1. Introduction Even simple molecules contain a rich set of internal degrees of freedom. When these internal states are controlled at the quantum level, they have many applications in fundamental physics [1,2] such as searches for new forces [3], the investigation of parity [4,5] and time-reversal [6,7] symmetries, or searches for time-variation of fundamental constants [8–10]. -

V Interstellar Molecules

V Interstellar Molecules Interstellar molecular gas was discovered in the 1940s with the observation of absorption bands from electronic transitions in CH, CH+, and CN superimposed on the spectra of bright stars. In the late 1960s, centimeter- and millimeter-wavelength radio observations detected emission from rotational transitions of OH (hydroxyl), CO (carbon monoxide), NH3 (ammonia), and H2CO (formaldehyde). The Copernicus satellite detected Far-UV absorption bands of H2 (the Lyman & Werner electronic transition bands) and HD in the early 1970s, and Lyman FUSE (launched in 1999) has detected diffuse H2 along nearly every line of sight it has looked (where it often gets in the way of lines from the extragalactic sources of interest to the observations!). Infrared observations beginning in the 1970s detected H2 in emission from forbidden rotational-vibrational transitions in the Near-IR, with advances in IR array detectors in the late 1990s greatly expanding studies of these transitions. It was in the 1980s, with the development of new millimeter receiver technology, that the study of interstellar molecules blossomed. Many molecular species were identified, and the field has grown sufficiently in depth that we can only give it the most basic treatment here. This section will focus on the basic physics of molecular line formation in the interstellar medium, and on the properties of giant molecular clouds. These notes assume a familiarity with basic molecular structure (electronic, vibrational, and rotational quantum states) as was covered in the Astronomy 823 course (Theoretical Spectroscopy). Persons using these notes outside of OSU can refer to standard texts (like Herzberg) for the necessary background information. -

Section 4 Molecular Rotation and Vibration

Section 4 Molecular Rotation and Vibration Chapter 13 Treating the full internal nuclear-motion dynamics of a polyatomic molecule is complicated. It is conventional to examine the rotational movement of a hypothetical "rigid" molecule as well as the vibrational motion of a non-rotating molecule, and to then treat the rotation- vibration couplings using perturbation theory. I. Rotational Motions of Rigid Molecules In Chapter 3 and Appendix G the energy levels and wavefunctions that describe the rotation of rigid molecules are described. Therefore, in this Chapter these results will be summarized briefly and emphasis will be placed on detailing how the corresponding rotational Schrödinger equations are obtained and the assumptions and limitations underlying them. A. Linear Molecules 1. The Rotational Kinetic Energy Operator As given in Chapter 3, the Schrödinger equation for the angular motion of a rigid (i.e., having fixed bond length R) diatomic molecule is h2/2m {(R2sinq)-1¶/¶q (sinq ¶/¶q ) + (R2sin2q)-1 ¶2/¶f 2 } y = E y or L2y /2mR2 = E y . The Hamiltonian in this problem contains only the kinetic energy of rotation; no potential energy is present because the molecule is undergoing unhindered "free rotation". The angles q and f describe the orientation of the diatomic molecule's axis relative to a laboratory-fixed coordinate system, and m is the reduced mass of the diatomic molecule m=m1m2/(m1+m2). 2. The Eigenfunctions and Eigenvalues The eigenvalues corresponding to each eigenfunction are straightforward to find because Hrot is proportional to the L2 operator whose eigenvalues have already been determined. The resultant rotational energies are given as: EJ = h2 J(J+1)/(2mR2) = B J(J+1) and are independent of M.