City of Clans Geoff Eckp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:450 洋楽アーティスト特集 放送日:2019/11/25~2019/12/01 「番組案内 (8時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~/12:00~/20:00~ 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■CHRIS BROWN 特集 (1) Run It! [Main Version] Chris Brown Yo (Excuse Me Miss) [Main Version] Chris Brown Gimme That Chris Brown Say Goodbye (Main) Chris Brown Poppin' [Main] Chris Brown Shortie Like Mine (Radio Edit) Bow Wow Feat. Chris Brown & Johnta Austin Wall To Wall Chris Brown Kiss Kiss Chris Brown feat. T-Pain WITH YOU [MAIN VERSION] Chris Brown TAKE YOU DOWN Chris Brown FOREVER Chris Brown SUPER HUMAN Chris Brown feat. Keri Hilson I Can Transform Ya Chris Brown feat. Lil Wayne & Swizz Beatz Crawl Chris Brown DREAMER Chris Brown ■CHRIS BROWN 特集 (2) DEUCES CHRIS BROWN feat. TYGA & KEVIN McCALL YEAH 3X Chris Brown NO BS Chris Brown feat. Kevin McCall LOOK AT ME NOW Chris Brown feat. Lil Wayne & Busta Rhymes BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE Chris Brown feat. Benny Benassi SHE AIN'T YOU Chris Brown NEXT TO YOU Chris Brown feat. Justin Bieber WET THE BED Chris Brown feat. Ludacris SHOW ME KID INK feat. CHRIS BROWN STRIP Chris Brown feat. Kevin McCall TURN UP THE MUSIC Chris Brown SWEET LOVE Chris Brown TILL I DIE Chris Brown feat. Big Sean & Wiz Khalifa DON'T WAKE ME UP Chris Brown DON'T JUDGE ME Chris Brown ■CHRIS BROWN 特集 (3) X Chris Brown FINE CHINA Chris Brown SONGS ON 12 PLAY Chris Brown feat. Trey Songz CAME TO DO Chris Brown feat. Akon DON'T THINK THEY KNOW Chris Brown feat. Aaliyah LOVE MORE [CLEAN] CHRIS BROWN feat. -

Rules and Regulations

Rules and Regulations Rules & Regulations | 02.12.21 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................4 ARTICLE I: DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................6 ARTICLE II: GENERAL CONDUCT .................................................................... 12 ARTICLE III: DOING BUSINESS AT THE AIRPORT .......................................... 16 ARTICLE IV: COMMUNICATION ........................................................................ 24 ARTICLE V: APRON OPERATIONS................................................................... 26 ARTICLE VI: MOTOR VEHICLES ....................................................................... 28 ARTICLE VII: FIRE AND SAFETY ...................................................................... 37 ARTICLE VIII: ACAA TENANT AND CONTRACTOR FIRE POLICY AND HAZARDOUS MATERIAL ................................................................................... 41 ARTICLE IX: SANITATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL ......................................... 46 ARTICLE X: SECURITY ...................................................................................... 49 ARTICLE XI: FUELING ....................................................................................... 55 ARTICLE XII: WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT ........................................................... 66 ARTICLE XIII: DEFINITIONS, NOTICE OF VIOLATIONS, ENFORCEMENT / PENALTIES ............................................................................... -

Gone Girl : a Novel / Gillian Flynn

ALSO BY GILLIAN FLYNN Dark Places Sharp Objects This author is available for select readings and lectures. To inquire about a possible appearance, please contact the Random House Speakers Bureau at [email protected] or (212) 572-2013. http://www.rhspeakers.com/ This book is a work of ction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used ctitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 2012 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Dark Places” copyright © 2009 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Sharp Objects” copyright © 2006 by Gillian Flynn All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flynn, Gillian, 1971– Gone girl : a novel / Gillian Flynn. p. cm. 1. Husbands—Fiction. 2. Married people—Fiction. 3. Wives—Crimes against—Fiction. I. Title. PS3606.L935G66 2012 813’.6—dc23 2011041525 eISBN: 978-0-307-58838-8 JACKET DESIGN BY DARREN HAGGAR JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY BERND OTT v3.1_r5 To Brett: light of my life, senior and Flynn: light of my life, junior Love is the world’s innite mutability; lies, hatred, murder even, are all knit up in it; it is the inevitable blossoming of its opposites, a magnicent rose smelling faintly of blood. -

Brentwood Comprehensive Plan

THE BOROUGH OF BRENTWOOD James H. Joyce - Mayor (1981 - 1997) Ronald A. Amoni,- Mayor (1998-2001) Brentwood Borouph Council (1994 - 1997) Brentwood Borouyh Council (1998 - 2001) Fred A Swanson - President Nancy Patton - President Nancy Patton - Vice President Scott Werner -Vice President Sonya C. Vernau David K. Schade Ronald A. Arnoni Raymond J. Schiffhauer Michael A. Caldwell Marie Landon David K. Schade Martin Vickless Raymond J. Schiffhauer Deborah E. Takach Borough Solicitor: James Perich, Esq. Borough Engineer: George Pitcher, Neilan Engineers Brentwood Administrative Office: Elvina Nicola Borough Treasurer: James L. Myron Brentwood Tax Office: Katherine Gannis Brentwood Police Department: George Swinney Brentwood Public Works Department: Thomas Kammermeier Brentwood Library: Monica Stoicovy Brentwood Borouph Planninp Commission Brenhvood Zoning HearinP Board Jerry Borst - Chairman Edward Szpara - Chairman Janice Iwanonkiw - Vice Chairperson Phil Hoebler - Vice Chairman Michael Means Robert Haas Michael Wooten Joanna McQuaide Rick Cerminaro Robert Hartshorn Sally Bucci Emanuel Perry Solicitor: Alan Shuckrow, Esq. Information Compiled and Supplied bv the Followinp: Brentwood Borough Council Brentwood Borough Planning Coinmission Brentwood Borough Citizen’s Advisory Committee Ilrcntwood Ilorough School District Ilrciit wood I3oroiigli Ilislorical Socicly Ilrcii~wood11oro1igIi Voliiiiiccr Fire I )cprirtiiiciil I~rciiiwoodIicoiioiiiic I)cvclopiiicii~ ( ‘orporiilioii Part I: THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Section 1: Introduction / Vision Statement -

Glass Facts July – September 2011

Glass Facts July – September 2011 play out in the continued recovery of all aspects of our SEGA Chairman’s economy as that money gets spent and then re–spent a number of times. That is if someone does not Message completely destroy our free market economy! As most of you are aware by now, Governor Scott signed HB 849 at the end of June. This bill from the Florida’s legislative process established the Glass and Glazing License as a mandatory Division II contractors license. A Certified Glass and Glazing Contractor license is now required to do any work involving glass both inside and outside of any residential or commercial building. Many in the construction industry welcome this important change. Building and Code Enforcement Departments across the state are especially glad that this change has taken place. They see it as an important part of the building process in insuring only qualified people do the glass and glazing Welcome from the SEGA Board of Directors on this work and do it correctly per code. beautiful “fall” morning! At least the calendar says that it is fall, but it is hard to tell that as the temperatures Even though the license has been a voluntary license continue to set record highs across the southeast. We for many years, this law caught many off guard. A all look forward to the cooler mornings and the lower review of the state licensing website shows that many high temperatures of the late fall and winter in Florida. people in our trade now recognize this requirement The promise of this natural occurrence every year and have taken steps to start the licensing process. -

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

November 18, 2020 Telephone Conference Meeting

PENNSYLVANIA LIQUOR CONTROL BOARD MEETING MINUTES WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 18, 2020 TELEPHONE CONFERENCE MEETING Tim Holden, Chairman Office of Chief Counsel Office of Retail Operations Mike Negra, Board Member Bureau of Licensing Bureau of Product Selection Mary Isenhour, Board Member Bureau of Human Resources Financial Report Michael Demko, Executive Director Bureau of Accounting & Purchasing Other Issues John Stark, Board Secretary PUBLIC MEETING – 11:00 A.M CALL TO ORDER ...................................................................................................................... Chairman Holden Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag Chairman Holden made an opening statement thanking everyone for their continued cooperation and understanding as the PLCB is dealing with COVID-19 and the need to meet in this telephonic fashion. Chairman Holden stated that we still face a very serious health crisis and though he was unable to provide updated statistics with regard to the number of Pennsylvanians affected by the virus, he reiterated the need for caution. OLD BUSINESS ................................................................................................................................ Secretary Stark A. Motion to approve previous Board Meeting Minutes of the October 28, 2020 meeting. Motion Made: Board Member Negra Seconded: Board Member Isenhour Board Decision: Unanimously agreed (3-0 vote) to approve previous Board Minutes. PUBLIC COMMENT ON AGENDA ITEMS The Board has reserved 10 minutes for Public Comment on printed agenda items. Lynn Wolfe stated that she wished to know the status of a license transfer pertaining to the purchase of a beer distributor and questioned if the transfer she was concerned about would be addressed during the meeting. Chairman Holden asked Ms. Wolfe if she had reviewed the agenda for the meeting and Ms. Wolfe indicated that she had not been able to determine whether or not the transfer appeared on the agenda. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

INSTITUTION Congress of the US, Washington, DC. House Committee

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 303 136 IR 013 589 TITLE Commercialization of Children's Television. Hearings on H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125: Bills To Require the FCC To Reinstate Restrictions on Advertising during Children's Television, To Enforce the Obligation of Broadcasters To Meet the Educational Needs of the Child Audience, and for Other Purposes, before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives, One Hundredth Congress (September 15, 1987 and March 17, 1988). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Energy and Commerce. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 354p.; Serial No. 100-93. Portions contain small print. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) -- Viewpoints (120) -- Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Advertising; *Childrens Television; *Commercial Television; *Federal Legislation; Hearings; Policy Formation; *Programing (Broadcast); *Television Commercials; Television Research; Toys IDENTIFIERS Congress 100th; Federal Communications Commission ABSTRACT This report provides transcripts of two hearings held 6 months apart before a subcommittee of the House of Representatives on three bills which would require the Federal Communications Commission to reinstate restrictions on advertising on children's television programs. The texts of the bills under consideration, H.R. 3288, H.R. 3966, and H.R. 4125 are also provided. Testimony and statements were presented by:(1) Representative Terry L. Bruce of Illinois; (2) Peggy Charren, Action for Children's Television; (3) Robert Chase, National Education Association; (4) John Claster, Claster Television; (5) William Dietz, Tufts New England Medical Center; (6) Wallace Jorgenson, National Association of Broadcasters; (7) Dale L. -

![MOVIES / TV by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 284 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3394/movies-tv-by-artist-no-of-tunes-284-1393394.webp)

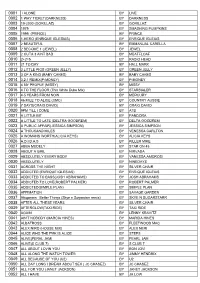

MOVIES / TV by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 284 ]

[ MOVIES / TV by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 284 ] 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA ABBA >> WATERLOO {K} ADAM SANDLER >> I WANT TO GROW OLD WITH YOU ADELE >> SKYFALL {K} AJR >> I'M READY {K} ANDY GRAMMER >> DON'T GIVE UP ON ME {K} ARETHA FRANKLIN >> RESPECT ARETHA FRANKLIN (BLUES BROTHERS) >> THINK ARIANA GRANDE >> DON'T CALL ME ANGEL {K} BARBARA STREISAND >> EVERGREEN BARBARA STREISAND AND BRIAN ADAMS >> I FINALLY FOUND SOMEONE BEATLES >> MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR {K} BEATLES >> SGT PEPPER'S LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND {K} BEATLES >> WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM MY FRIENDS {K} BEE GEES >> MORE THAN A WOMAN BEE GEES >> NIGHT FEVER {K} BEE GEES >> YOU SHOULD BE DANCING {K} BERLIN >> TAKE MY BREATH AWAY {K} BILL MEDLEY AND JENNIFER WARNES >> THE TIME OF MY LIFE BILL MEDLEY AND JENNIFER WARNES >> TIME OF MY LIFE BILLY JOEL >> ALL SHOOK UP {K} BLUES BROTHERS >> STAND BY YOUR MAN BOB SEGER >> C'EST LA VIE {K} BOBBY MC FERRIN >> DON'T WORRY BE HAPPY {K} BON JOVI >> BED OF ROSES {K} BOOMKAT >> WASTING MY TIME BROTHERS3 >> THE LUCKY ONES {K} CELINE DION >> MY HEART WILL GO ON CHEF >> CHOCOLATE SALTY BALLS CHEF >> SIMULTAEOUS CHRIS ISAAK >> BABY DID A BAD BAD THING {K} CHRIS SEBASTIAN >> BED FOR 2 {K} CHRISTINA AGUILERA >> HAUNTED HEART CHRISTINA AGUILERA - LIL' KIM - PINK - MYA >> LADY MARMALADE {K} CHRISTINA PERRI >> A THOUSAND YEARS {K} CHRISTINE AGUILERA AND MISSY ELLIOTT >> CAR WASH {K} CHUCK BERRY >> YOU CAN NEVER TELL COUNTING CROWS >> ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE {K} CYRUS VILLANUEVA >> STONE D12 >> RAP GAME DAMI IM >> ALIVE {K} DAMI IM >> SOUND OF SILENCE -

Indigenous Art in Urban Renewal: the Emergence and Development of Artistic Communities in Midwestern Post-Industrial Cities

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 3-2012 Indigenous art in urban renewal: The emergence and development of artistic communities in midwestern post-industrial cities William Covert DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Covert, William, "Indigenous art in urban renewal: The emergence and development of artistic communities in midwestern post-industrial cities" (2012). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 114. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/114 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIGENOUS ART IN URBAN RENEWAL: THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF ARTISTIC COMMUNITIES IN MIDWESTERN POST-INDUSTRIAL CITIES A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science March, 2012 BY William Covert School of Public Service College of Liberal Arts and Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois ABSTRACT Art has been shown in the academic literature to have potentially transformative effects on urban neighborhoods. Artistic communities in particular strengthen community participation and leadership, create a nightlife that can support business, low crime, and attract tourists. Policy makers, however, often lack understanding of how artist communities function and how these enclaves can enhance the development and sustainability of neighborhoods. -

Constructing Campus Conflict, Appendices

Challenging the Right, Advancing Social Justice CONSTRUCTING CAMPUS CONFLICT Antisemitism and Islamophobia on U.S. College Campuses, 2007-2011 2007-2011: Appendices Senior Editor Chip Berlet Managing Editor Debra Cash Associate Editor Maria Planansky Political Research Associates (PRA) is a social justice think tank devoted to supporting movements that are building a more just and inclusive democratic society. We expose movements, institutions, and ideologies that undermine human rights. Copyright ©2014, Political Research Associates Political Research Associates 1310 Broadway, Suite 201 Somerville, MA 02144-1837 www.politicalresearch.org design by rachelle galloway-popotas, owl in a tree CONTENTS SURVEY OF MSA STUDENTS ................................................................................................................. 4 ISLAMO-FACISM AWARENESS WEEK (IFAW) 2007 ......................................................................... 7 TRAUMA AND PREJUDICE ................................................................................................................... 10 ADL AND THE PARK51 CONTROVERSY ......................................................................................... 12 RENE GIRARD AND MIMETIC SCAPEGOATING ............................................................................. 13 BIBLIOGRAPHIES ......................................................................................................................................15 Selected LIST OF INCIDENTS DESCRIBED AS ANTISEMITIC ...........................................