Recent Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Function and Evolution of Egg Colour in Birds

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2012 The function and evolution of egg colour in birds Daniel Hanley University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Hanley, Daniel, "The function and evolution of egg colour in birds" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 382. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/382 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE FUNCTION AND EVOLUTION OF EGG COLOURATION IN BIRDS by Daniel Hanley A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through Biological Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2011 © Daniel Hanley THE FUNCTION AND EVOLUTION OF EGG COLOURATION IN BIRDS by Daniel Hanley APPROVED BY: __________________________________________________ Dr. D. Lahti, External Examiner Queens College __________________________________________________ Dr. -

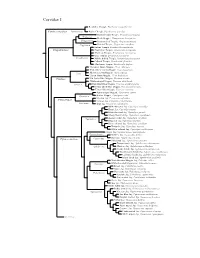

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

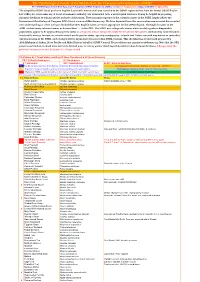

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

SE China and Tibet (Qinghai) Custom Tour: 31 May – 16 June 2013

SE China and Tibet (Qinghai) Custom Tour: 31 May – 16 June 2013 Hard to think of a better reason to visit SE China than the immaculate cream-and-golden polka- dot spotted Cabot’s Tragopan, a gorgeous serious non-disappointment of a bird. www.tropicalbirding.com The Bar-headed Goose is a spectacular waterfowl that epitomizes the Tibetan plateau. It migrates at up to 27,000 ft over the giant Asian mountains to winter on the plains of the Indian sub-continent. Tour Leader: Keith Barnes All photos taken on this tour Introduction: SE and Central China are spectacular. Both visually stunning and spiritually rich, and it is home to many scarce, seldom-seen and spectacular looking birds. With our new base in Taiwan, little custom tour junkets like this one to some of the more seldom reached and remote parts of this vast land are becoming more popular, and this trip was planned with the following main objectives in mind: (1) see the monotypic family Pink-tailed Bunting, (2) enjoy the riches of SE China in mid-summer and see as many of the endemics of that region including its slew of incredible pheasants and the summering specialties. We achieved both of these aims, including incredible views of all the endemic phasianidae that we attempted, and we also enjoyed the stunning scenery and culture that is on offer in Qinghai’s Tibet. Other major highlights on the Tibetan plateau included stellar views of breeding Pink-tailed Bunting (of the monotypic Chinese Tibetan-endemic family Urocynchramidae), great looks at Przevalski’s and Daurian Partridges, good views of the scarce Ala Shan Redstart, breeding Black-necked Crane, and a slew of wonderful waterbirds including many great looks at the iconic Bar-headed Goose and a hoarde of www.tropicalbirding.com snowfinches. -

Photospot – Pander's Ground Jay Podoces Panderi

Sandgrouse-080723:Sandgrouse 7/23/2008 12:51 PM Page 204 PHOTOSPOT— Pander’s Ground Jay Podoces panderi Plate 1. Pander’s Ground Jay Podoces panderi. © Tim Loseby Pander’s Ground Jay Podoces panderi is a shrubs. It gives a clear ringing call from bush desert bird occurring in the Middle Asian tops especially in early morning or evening countries of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and and is usually met with in pairs or family par- Kazakhstan (Cowan 1996, Madge & Burn ties. It feeds along sandy tracks, digging at 1999, Wassink & Oreel 2007). It appears close- animal droppings and rummaging at bases of ly related to the sandy- buff Pleske’s Ground bushes. It has the habit of creating food stor- Jay of Iran (and probably of bordering areas in age spots by burying food in sand. It is a seed Afghanistan and Pakistan), another desert eater, though insectivorous in spring and bird (Cowan 2000, Goodwin 1986, summer when prey items can include small Hamedanian 1997, Rasmussen & Anderton lizards. Nests are usually placed up to a metre 2005). These are cursorial birds reminiscent of above the ground within bushes and it lays a Cream- coloured Courser Cursorius cursor and clutch of four to five eggs. Eggs have been Hoopoe Lark Alaemon alaudipes. found between late February and late May Pander’s Ground Jay is a bird of sandy and it has an incubation period of 16–19 days desert with dunes and good coverage of (Madge & Burn 1999). 204 Sandgrouse 30 (2008) Sandgrouse-080723.qxp:Sandgrouse 30/7/08 09:49 Page 205 Tim Loseby’s bird (Plate 1), active on the REFERENCES ground, exhibits at least two points of interest. -

Podoces Ground-Jays and Roads: Observations from the Taklimakan Desert, China

Forktail 27 (2011) SHORT NOTES 109 Podoces ground-jays and roads: observations from the Taklimakan Desert, China TIZIANO LONDEI Introduction trail of horses’. A ‘definite preference for caravan paths’ has also The ground-jays are Central Asian desert birds forming a genus been reported for Turkestan Ground-jays feeding on dung, garbage with four species: the Iranian Ground-jay Podoces pleskei endemic and dropped grains (Dementiev & Gladkov 1954), while Iranian to Iran, Turkestan Ground-jay P. panderi, Mongolian Ground-jay P. Ground-jays have been observed in the early morning and late hendersoni and Xinjiang Ground-jay P. biddulphi, the last endemic afternoon running in search of spilt grains on roads between villages to north-western China. These corvids have obvious specialisations (Hamedanian 1997). Here I report an exploratory study that might to ground-living in deserts (e.g. Londei 2004). Their typical habitat make the basis for more structured studies aiming at both the status is barren ground interspersed with scrub, as they need some of the ground-jays and their possible use in road ecology. vegetation for the seeds and small animals that form their diet, as well as for shelter and nesting. Their water sources are little known. Study area and methods They are still little-studied birds and their conservation status is Attendance at a road of recent construction has been observed in generally poorly known, except for the assumption of a common the Xinjiang Ground-jay, found around temporary car parks, garbage decrease in numbers owing to habitat degradation (Marzluff 2009). stations and road maintenance camps along the Tarim Desert As usual with animals of habitats difficult for humans to access, Highway (Ma Ming & Kwok Hon Kai 2004). -

Birds As Seed Dispersers in Deserts: Suggestions from the Ground-Jays

Londei Avian Res (2021) 12:13 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-021-00248-7 Avian Research LETTER TO THE EDITOR Open Access Birds as seed dispersers in deserts: suggestions from the ground-jays Tiziano Londei* Abstract The study of seed dispersal, biotic seed dispersal, and even less, the role of birds in it, have been almost neglected in deserts. Virtually absent from the literature on seed dispersal are the ground-jays, genus Podoces, four species of the crow family that inhabit arid environments, even true deserts, from Iran to Mongolia. Although they are omnivorous, they seem to mainly depend on the seeds of desert plants during the cold season. There are suggestions in sparse literature that they may contribute to seed dispersal similarly to several corvid species of other climates, by caching seeds in useful microsites to save them for later consumption and thus actually favoring the germination of the seeds they fail to recover. Future research might beneft from comparison with the vast literature on their better-known seed-caching relatives. This paper is aimed at providing basic information on each ground-jay species and some sug- gestions for investigating their likely symbiosis with desert plants, with possible applications to the maintenance and restoration of vegetation in a very extended arid zone. Keywords: Central Asia, Desert birds, Podoces ground-jays, Seed dispersal, Synzoochory Correspondence useful microsites to save seeds for later consumption. Deserts have received less attention than other climates Such sites might also be suitable for seedling establish- for seed dispersal for at least two reasons easily found in ment and the animal might fail to recover all the cached literature (e.g. -

Pseudopodoces Humilis, a Misclassified Terrestrial Tit (Paridae) of Tiie Tibetan Plateau: Evolutionary Consequences of Shifting Adaptive Zones

/6/s(2003), 145, 185-202 Pseudopodoces humilis, a misclassified terrestrial tit (Paridae) of tiie Tibetan Plateau: evolutionary consequences of shifting adaptive zones HELEN F. JAMES,^* PER G.P. ERICSON,^ BETH SLIKAS,^ FU-MIN LEI*, FRANK B. GILL^ & STORRS L. OLSON^ ^ Department of Systematic Biology, National Museum of Natural History, Smitiisonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560, USA ^Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden ^Department of Research, National Zoological Park, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20008, USA '^Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 19 Zhongguancun Road, Haidian District, Beijing 100080, China ^National Audubon Society 700 Broadway New York, NY 10003, USA Pseudopodoces humilis (Hume's Ground-Jay) is a small passerine bird that inhabits the high rocky steppes of the Tibetan (Qinghai-Xizang) Plateau. Although it was long classified as a small species of ground jay (Podoces), two previous anatomical studies cast doubt on its assignment to the Corvidae (crows and jays). We studied the evolutionary relationships of Pseudopodoces using three independent datasets drawn from comparative osteology, the nuclear c-myc gene, and the mitochondrial cytochrome h gene. All three datasets agree on the placement o{ Pseudopodoces in the family Paridae (tits and chickadees). The cytochrome h data further suggest that Pseudopodoces may be closest to the Great Tit Parus major species group. Pseudopodoces is the only species of parid whose distribution is limited to treeless terrain. Its evolutionary relationships were long obscured by adaptations to open habitat, including pale, cryptic plumage; a long, decurved bill for probing in crevices among rocks or in the ground; and long legs for terrestrial locomotion. -

Qinghai, Shanxi & Sichuan

Central China: Qinghai, Shanxi & Sichuan Custom Tour: 2 – 17 June 2012 We were in Giant Panda country throughout this trip, and although we found fresh scat, it was never our intention to track this near mythical mammal. However we did get lucky with a troop of argumentative and scarce Golden Snub-nosed Monkeys in Shanxi. www.tropicalbirding.com Tour Leader: Keith Barnes Male Temminck’s Tragopan on the road! How about that…this was one of 6 pheasant species seen well from the roadside on this tour. Introduction: Central China is spectacular. Both visually stunning and spiritually rich, and it is home to many scarce, seldom-seen and spectacular looking birds. With our new base in Taiwan, little junkets like this one to some of the more seldom reached and remote parts of this vast land are becoming more popular, and this custom trip was planned with the following main objectives in mind: (1) see the Pink-tailed Bunting, (2) see the Crested Ibis which was once in the mid 70’s nearly extinct and (3) see as many pheasants as possible without subjecting the clients to trail walking, which they do not enjoy. We achieved all three of these aims, including 10 species of phasianids, and added for good measure the very first bird tour sightings of the enigmatic Blackthroat (a bird that’s breeding range was unknown until last year), a great selection of phasianids, including the endemic Rusty-necklaced Partridge and a series of great road-side chickens including magical views of Temminck’s Tragopan. But there were a lot of other star attractions, including the immaculate Henderson’s Ground-Jay, and a party of four Tibetan Snowcocks that stood on a www.tropicalbirding.com high ridge. -

Podoces Biddulphi)

sustainability Article Water, Food Availability, and Anthropogenic Influence Determine the Nesting-Site Selection of a Desert-Dwelling Bird, Xinjiang Ground-Jay (Podoces biddulphi) Yuping Tong 1,2,3,4, Feng Xu 1,2,3,4,* , David Blank 5 and Weikang Yang 1,2,3,* 1 State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] 2 The Specimen Museum of Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China 3 Mori Wildlife Monitoring and Experimentation Station, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mori 831900, China 4 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 5 CAS Research Center for Ecology and Environment of Central Asia, Bishkek 720001, Kyrgyzstan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.X.); [email protected] (W.Y.) Abstract: Nesting-site selection is an important aspect of the breeding process in birds, as it usually determines nesting and breeding successes. Many factors can affect bird nest-site selection, including anthropogenic disturbance. In an extreme desert environment, such as the Taklamakan Desert in China, birds’ survival pressure is high, especially for rare species such as the Xinjiang Ground-jay (Podoces biddulphi). We studied nest-site selection in this species from March 2017 to May 2019. A Chi-square test, independent sample t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, and generalized linear models Citation: Tong, Y.; Xu, F.; Blank, D.; were applied to possible nest-site selection factors for Xinjiang Ground-jays. -

Brochure-2021.Pdf

1 Birdfinders’ website, www.birdfinders.co.uk, is updated frequently with tour news, tour reports and images and the availability of places on future holidays. Our website is regularly the highest rated of any UK birdwatching tour company on the FatBirder web ring of the top one thousand two hundred bird-related websites. Our office manager, Helen Heyes, is available Tuesdays and Fridays from 09.00 to 17.00 and, when not on tour, Vaughan and Svetlana are available from 09.00 to 18.00 every day. We look forward to seeing you on a birding holiday of a lifetime. Vaughan and Svetlana Ashby and all the team. The Birdfinders team is pleased to present you with our programme of birdwatching holidays in 2021, our twenty-eighth year of operation. Full itineraries for all of our tours can be found on our website but, if you do not have access to the internet, do not hesitate to contact us and we will send you paper copies of any tours in which you have an interest. Similarly, our full terms and conditions, single and other supplements, insurance, voluntary carbon offset and bios of all our leaders can be found on our website. www.birdfinders.co.uk Birdfinders holidays range from four-day breaks to twenty-four day vacations and from single-centre trips to extensive tours involving multiple locations. Regardless of type, our holidays are consistently successful in terms of finding a high proportion of the sought-after specialities due to our carefully devised itineraries and knowledgeable, experienced leaders, many of whom are resident in the country in question. -

Breeding Activities and Success of Pleske's Ground Jay Podoces Pleskei in Touran Biosphere Reserve, Semnan Province, Iran

Podoces, 2010, 5(1): 35–41 Breeding Activities and Success of Pleske's Ground Jay Podoces pleskei in Touran Biosphere Reserve, Semnan Province, Iran NOOSHIN SATEI* 1, MOHAMMAD KABOLI 2, SAEID CHERAGHI 1, MAHMOUD KARAMI 2, MITRA SHARIATI NAJAFABADI 2 & REZA GOLJANI 1 1 Biodiversity & Habitats Division, Faculty of Environment & Energy, Science & Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, IRAN 2 Department of Fisheries and Environment, Faculty of Natural Resources, University of Tehran, Tehran, IRAN * Correspondence Author. Email: [email protected] Received 11 November 2009; accepted 15 April 2010 Abstract: The breeding biology of Pleske's Ground Jay Podoces pleskei was studied on the Mehrano Plain (in Touran Biosphere Reserve, Iran) from February to May in 2007 and 2008. Nest sites were located mainly in the top centre of dense vegetation, such as thorny bushes of Atraphaxis spinosa, Ephedra intermedia and Zygophyllum eurypterum . The cup- shaped nests in Atraphaxis bushes and dome-shaped nests in other species shrubs like Ephedra and Zygophyllum were built from thin branches and twigs that help protect nestlings against direct radiation from the sun. Clutch sizes varied from three to six eggs (4.1±0.6 mean ± SD) laid at the end of February. Hatching occurred within 17.5±1.5, mid- March. The probabilities of survival were: eggs' during the incubation period 0.436, chicks during hatching period 0.86 and nestlings 0.963. The overall breeding success from the beginning of the incubation period until fledging was 0.36. The maximum mortality rate was calculated during the incubation period. Predators, such as Eastern Desert Monitor Varanus griseus caspius were important threats affecting egg survival.