Managing Trumps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

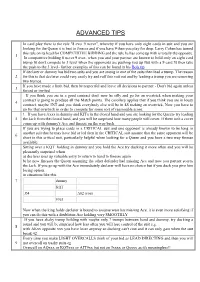

Advanced Tips

ADVANCED TIPS In card play there is the rule "8 ever 9 never", whereby if you have only eight cards in suit and you are looking for the Queen it is best to finesse and if you have 9 then you play for drop. Larry Cohen has turned this rule on its head for COMPETITIVE BIDDING and the rule he has come up with is totally the opposite. 1 In competitive bidding 8 never 9 ever- when you and your partner are known to hold only an eight card trump fit don't compete to 3 level when the opponents are pushing you up But with a 9 card fit then take the push to the 3 level- further examples of this can be found in his Bols tip If declarer or dummy has bid two suits and you are strong in one of the suits then lead a trump. The reason 2 for this is that declarer could very easily try and ruff this suit out and by leading a trump you are removing two trumps. If you have made a limit bid, then be respectful and leave all decisions to partner - Don't bid again unless 3 forced or invited If you think you are in a good contract don't now be silly and go for an overtrick when making your contract is going to produce all the Match points. The corollary applies that if you think you are in lousy 4 contract, maybe 3NT and you think everybody else will be in 4S making an overtrick, Now you have to go for that overtrick in order to compete for some sort of reasonable score. -

Bridge Glossary

Bridge Glossary Above the line In rubber bridge points recorded above a horizontal line on the score-pad. These are extra points, beyond those for tricks bid and made, awarded for holding honour cards in trumps, bonuses for scoring game or slam, for winning a rubber, for overtricks on the declaring side and for under-tricks on the defending side, and for fulfilling doubled or redoubled contracts. ACOL/Acol A bidding system commonly played in the UK. Active An approach to defending a hand that emphasizes quickly setting up winners and taking tricks. See Passive Advance cue bid The cue bid of a first round control that occurs before a partnership has agreed on a suit. Advance sacrifice A sacrifice bid made before the opponents have had an opportunity to determine their optimum contract. For example: 1♦ - 1♠ - Dbl - 5♠. Adverse When you are vulnerable and opponents non-vulnerable. Also called "unfavourable vulnerability vulnerability." Agreement An understanding between partners as to the meaning of a particular bid or defensive play. Alert A method of informing the opponents that partner's bid carries a meaning that they might not expect; alerts are regulated by sponsoring organizations such as EBU, and by individual clubs or organisers of events. Any method of alerting may be authorised including saying "Alert", displaying an Alert card from a bidding box or 'knocking' on the table. Announcement An explanatory statement made by the partner of the player who has just made a bid that is based on a partnership understanding. The purpose of an announcement is similar to that of an Alert. -

New South Wales Bridge Association ♠ ♥ Newsletter ♦ ♣

Vol.42 No 8 March 2016 – May 2016 New South Wales Bridge Association ♠ ♥ Newsletter ♦ ♣ Editor: Steve Hurley Chairman’s corner and is particularly keen on supporting clubs around the State. Watch out for more communications After the Gold Coast Congress, the bridge season from her! Work commitments also mean that Steve tends to quieten down a little but we are now into Hurley is stepping down as Newsletter editor. I qualifying events for assorted State and National thank him for his work over the last 2 years. We do competitions. The 2016 NSW State Teams have all not as yet have a direct replacement but we are been selected and will soon be heading to the ANC considering a revamp of the publication, possibly in Brisbane - we wish them all well. with a move to a more electronic format, perhaps alongside eCongress News. We will keep you NSWBA continues to provide financial assistance to informed. various bridge support activities around NSW. Tony Howes has run director training in Tamworth and Happy bridging Sydney and Joan Butts has run teacher training in Orange. Cath Whiddon is now going to be assisting Julian Foster Joan which should enable more of these teacher training courses to be delivered. A marketing workshop by Sandra Mulcahy is coming up on June Just bid it 3rd in Sydney and Sandra will then be providing a summary to our Regional Representatives meeting Far too many of my opponents these days seem to the next day with a view to running similar play a system best described as "don't worry, just workshops in regional areas. -

C:\My Documents\Adobe\Boston Fall99

Presents They Had Their Beans Baked In Beantown Appeals at the 1999 Fall NABC Edited by Rich Colker ACBL Appeals Administrator Assistant Editor Linda Trent ACBL Appeals Manager CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................... iii The Expert Panel.................................................v Cases from San Antonio Tempo (Cases 1-24)...........................................1 Unauthorized Information (Cases 25-35)..........................93 Misinformation (Cases 35-49) .................................125 Claims (Cases 50-52)........................................177 Other (Case 53-56)..........................................187 Closing Remarks From the Expert Panelists..........................199 Closing Remarks From the Editor..................................203 Special Section: The WBF Code of Practice (for Appeals Committees) ....209 The Panel’s Director and Committee Ratings .........................215 NABC Appeals Committee .......................................216 Abbreviations used in this casebook: AI Authorized Information AWMPP Appeal Without Merit Penalty Point LA Logical Alternative MI Misinformation PP Procedural Penalty UI Unauthorized Information i ii FOREWORD We continue with our presentation of appeals from NABC tournaments. As always, our goal is to provide information and to foster change for the better in a manner that is entertaining, instructive and stimulating. The ACBL Board of Directors is testing a new appeals process at NABCs in 1999 and 2000 in which a Committee (called a Panel) comprised of pre-selected top Directors will hear appeals at NABCs from non-NABC+ events (including side games, regional events and restricted NABC events). Appeals from NABC+ events will continue to be heard by the National Appeals Committees (NAC). We will review both types of cases as we always have traditional Committee cases. Panelists were sent all cases and invited to comment on and rate each Director ruling and Panel/Committee decision. Not every panelist will comment on every case. -

W.Ide'e'lections ,'T.Oda,'! / an .' ••••.••• Whiz, .A",1 Powihere Ar

HQly Ballot Box! Cc;lrrJ,pus;~W.ide'E'lections ,'T.oda,'! / An .' ••••.••• Whiz, .a",1 POWIHere ar. tIM four (count, 'em) 'undidatel fer Student Body President. Golly,' There's Birth Control Jo., DI- Genova, who proposed putting a . Playboy Pinmate on the Bat ~ig-c. nal ("It would attract his atten- I tion quicker"); there's Bumbling Bob "Don'f Rock the Boat" Engle, who has come out strongly for the and crumpets on 'campus; there's Rich "Filibustering Philosophizer", D~vis, darling' of the"Old -Coall- tion"set; 'anet there's Smiling Jim - "Time For a, Change" lied who is (a bit unusual in that he hasn't / been too aware of what the heck was going on due to being out of town but he does seem more con- cerned for the" students than for himself. And he goes to Council meetingsl, ZAPI There're your choices: Ranting Radical, Rocking Chair Reactionary, lumbering Joe DI Genova , '1M L••• · Rich Davll Bob Engle . , Wow I . liberal, or, Well-meaning Mod· Zapl Babiesl Holy Hollererl Gee Whizl. 'erate.GOll YI GEE WHIZI University of Cincinnati N,-E,W'S'"R"E 'O,ORD' Vol. UII Cinucinnati, Ohio, April 7, 1966 NO. 23 \ \ SC.Cans Refere~dum; ~~ni9r ,c;l~ss' To ~ponsor .--~ -'l-S---=Membe~s,-Absent:'-'G- -. 'zd-' y-',:,-t,· "'-'S··L, .I'''S· " • by Judy ";"Carty was not printed up b~ the ~om. '. [fa ua-et-- C-nOO -+- etnlDQr, mittee. -," ~ The propos~d ~~u~eP,t Council F~r an alternate' proposal, Mr. by Dave Schwa in • help a career, and in what ways referendum,msbgated by .NR Wrigh~ c,mov,ed_.,,that ~a;<::enstitu.- .'., . -

Diana's Fun with Bridge

Diana’s Fun With Bridge July, 2020 Some great news regarding my lessons. A fantastic new program has been developed for teachers that I am in the process of learning. It will mean that my lessons will be on line, however, I can still give you my great Power Point teachings with the added feature of playing interactive hands. It may be a bit of time before I receive my training as This is a video that really the developers can only train up to five teachers a day starts to make you think and and there is quite a list ahead of me. Will keep you will help prepare you for my posted. Naturally, I will be teaching in person as soon Defence Level 11 lessons. If as it is allowed. you can’t access it by clicking below then copy and paste it Level 1 Defence - will be a repeat to Google or Safari. Level 1 Play of the Hand - will be a repeat. Level 2 Defence new. These lessons will bring your https://www.youtube.com/wat defence to a whole new level. ch?v=8d-Oplsa4cA Level 2 Play of the Hand new. Each lesson will cover only one subject. Lesson one will be on endplays. Basics on counting cards. Lessons two Squeezes. Lesson three cross-ruff. The final lesson is a fun lesson on deception. https://www.youtube.com/wat Slams – two informative lessons on how and when to ch?v=0NKa3zHoizI bid your slams. Major suit raises. https://www.youtube.com/wat ch?v=A-Aw7e4iLzg 1 One very important hand evaluation that is commonly overlooked is TIP the power of nines and tens in your hand. -

BR 20.6 - When NOT to Ruff : Loser on Loser Play

BR 20.6 - When NOT to ruff : Loser on Loser play In some situations it is to your advantage not to ruff. In such cases you invariably drop a loser of one suit onto a loser in another suit. This generally occurs in three different scenarios. 1. When, by reducing your trump length through ruffing, you may lose trump control 2. When by not ruffing you may develop a winner in the suit 3. When you are in danger of being over ruffed (Down - Up) Example 7 (Not losing trump control) Declarer is in a 1D contract. North leads the King of Hearts, then the Ace, followed by the Heart Queen. What do you do at trick 3? If you ruff the trick you will have only three trumps left in your hand. If Opponents trumps break 4-2, which is most likely, you will lose trump control and never be able to set up winners in the Club suit. Declarer Dummy ♦ - K Q J 4 ♦ - 10 9 5 ♠ - A K 6 ♠ - 9 7 3 ♥ - 8 2 ♥ - 9 5 4 ♣ - Q 8 7 2 ♣ - K J 10 3 Do therefore a loser on loser play and discard you small Spade loser on the third Heart trick. Declarer Dummy ♦ - K Q J 4 ♦ - 10 9 5 ♠ - A K ♠ - 9 7 3 ♥ - ♥ - ♣ - Q 8 7 2 ♣ - K J 10 3 Now if Opponents continue with a 4th Heart lead you can ruff it in Dummy with the 10, and the 4 card trump holding in your own hand remains intact. In essence what you have done is transferring your Spade loser to become a Heart loser instead. -

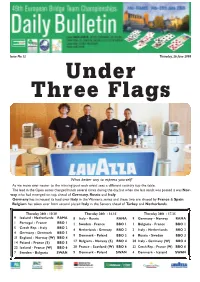

What Better Way to Espress Yourself! As We Move Ever Nearer to the Winning Post Each Event Sees a Different Country Top the Table

Issue No.12 Thursday, 26 June 2008 Under Three Flags What better way to espress yourself! As we move ever nearer to the winning post each event sees a different country top the table. The lead in the Open series changed hands several times during the day, but when the last result was posted it was Nor- way who had emerged on top, ahead of Germany, Russia and Italy. Germany has increased its lead over Italy in the Women’s series and these two are chased by France & Spain. Belgium has taken over from second placed Italy in the Seniors ahead of Turkey and Netherlands. Thursday 26th - 10.30 Thursday 26th - 14.15 Thursday 26th - 17.35 9 Iceland - Netherlands RAMA 8 Italy - Russia RAMA 9 Germany - Norway RAMA 1 Portugal - France BBO 1 1 Sweden - France BBO 1 1 Bulgaria - France BBO 1 5 Czech Rep. - Italy BBO 2 4 Netherlands - Germany BBO 2 3 Italy - Netherlands BBO 2 4 Germany - Denmark BBO 3 9 Denmark - Poland BBO 3 6 Russia - Sweden BBO 3 31 England - Norway (W) BBO 4 14 Poland - France (S) BBO 5 17 Belgium - Norway (S) BBO 4 30 Italy - Germany (W) BBO 4 23 Iceland - France (W) BBO 6 30 France - Scotland (W) BBO 6 22 Czech Rep. - France (W) BBO 6 7 Sweden - Bulgaria SWAN 9 Denmark - Poland SWAN 4 Denmark - Iceland SWAN 49th EUROPEAN BRIDGE CHAMPIONSHIPS Pau, France WOMEN TEAMS PROGRAM SENIOR TEAMS PROGRAM ROUND 20 10.30 ROUND 14 10.30 Table Home Team Visiting Team Table Home Team Visiting Team 21 CZECH REP. -

![Bridge in the Menagerie [Electronic Resource] / Victor Mollo](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9102/bridge-in-the-menagerie-electronic-resource-victor-mollo-1109102.webp)

Bridge in the Menagerie [Electronic Resource] / Victor Mollo

Master Point Press • Toronto, Canada Text © 2013 The Estate of Victor Mollo Cover image and illustrations © 2013 Bill Buttle All rights reserved. It is illegal to reproduce any portion of this material, except by special arrangement with the publisher. Reproduction of this material without authorization, by any duplication process whatsoever, is a violation of copyright. Master Point Press 331 Douglas Ave. Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5M 1H2 (416)781-0351 Email: [email protected] Websites: www.masterpointpress.com www.teachbridge.com www.bridgeblogging.com www.ebooksbridge.com Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Mollo, Victor Bridge in the menagerie [electronic resource] / Victor Mollo. Short stories. Electronic monograph. Issued also in print formats. ISBN 978-1-55494-240-4 (PDF).--ISBN 978-1-55494-472-9 (EPUB).--ISBN 978-1-55494-723-2 (MOBI) I. Title. PR6063.O43B75 2013 823’.914 C2013- 900123-9 Editor Ray Lee Copyeditor/Interior format Sally Sparrow Cover and interior design Olena S. Sullivan/New Mediatrix Publisher’s Foreword Back in the 1980s, while working for Macmillan Publishing, I attended a sales meeting at which a newly discovered, and therefore previously unpublished, work by Ernest Hemingway was announced. Later that evening, I was chatting to the editor who had had the good fortune to work on this manuscript, and couldn’t resist asking him what the experience had been like. ‘Well,’ he replied, ‘he wasn’t a bad writer, you know.’ It has been my good fortune to undertake the bridge equivalent of his experience — to work on editing and publishing a new edition of Victor Mollo’s Bridge in the Menagerie, a book that is included in absolutely everybody’s list of the top ten books ever written on the game of bridge. -

Commentary for the World Wide Bridge Contest Set 8

Commentary for the World Wide Bridge Contest Set 8 – Saturday 2nd June 2018 Thank you for participating in the 2018 WWBC – we hope that, win or lose, you enjoyed the hands and had fun. All the results can be found at www.ecatsbridge.com/sims as normal - just look for the results for the day you played. Full details of the Contest itself can be found at http://www.worldbridge.org/competitions/the-wbf-simultaneous-event/wwbc/ We hope you have enjoyed this last set of the WWBC heats – there are no more in 2018 but don’t forget to join us again in 2019! You could also consider playing in one of the Simultaneous events to raise funds to support Youth Bridge – these are held on the following dates in 2018: Monday 13th August Wednesday 15th August Monday 15th October Wednesday 17th October Monday 10th December Wednesday 12th December These events in support of Youth Bridge are simply fund raising so the entry fee is kept very low- just US$ 3.00, € 2.50, or £ 1.90 per pair (note ... per PAIR). WBF Year Points will be awarded to the leading pairs from each heat. Please click here to read more about how the WBF works to support Youth Bridge. Finally - the World Championships are in Orlando this year, from 21st September - 6th October. All the events are transnational, and there are Teams and Pairs events in all categories – Open, Women’s Senior and Mixed. There is also a Junior Triathlon and a number of side games. And you .. -

Vote Battle Escalates It Would Provide $500,000 for Low- Was Not Available for Comment This HARTFORD (UPI) - First Lady Mrs

24 - EVENING HERALD, Thurs., March 20. 1980 Re-arrest due “My Safe Deposit “I write ‘I have a 90<lay Notice “For the fastest bank ‘Our place was really ready for Box? Costs me checks—earn Savings Account. interest— go winter—our * less than interest at Perfect timing in abuse case for a 6-Month bank’s Home a dollar the same time. for me.” Money Improvement Hi a month.” AN.O.W. Frances Bartolotta MANCHESTER - Patricia The second charge against Ms. Maricet did it.’’ Manchester Crouse, 20, of 34 Williams St., will be Crouse stems from alleged abuse of ^Stanley Prachniak Account’s Certificate.’ David Eddy re-arrested this afternoon and her other daughter, four -year-old Coventry Manchester a good deal.” Kristine, who was taken to Ronald T. Herpst charged with a second count of risk A l Packer of injury to a minor in connection Manchester Memorial Hospital after Glastonbury Manchester V<rt. XCIX. No. 146 — Manohottof. Conn..-Friday. March ?1,1960 20rp Singly Copy • 15r( Home. Delivered with the case of child abuse, police police arrested Ms. Crouse and said. Wilson. Her injuries, described as minor, led to the second charge. Ms. Crouse’s boyfriend, Steven A. Kristine was released Tuesday and Wilson, 26, a soldier stationed at has been placed in a foster home by Aberdeen Proving Grounds in the State Department of Children and Maryland, was charged with first- Youth Services. degree assault, risk of injury and According to an autopsy report cruelty to persons in connection with Wednesday, Amy died Tuesday about the bea.ting death of Amy Crouse, 13- 4:30 p.m. -

Declarer Play Course – Fall 2014

DECLARER PLAY 2014 DECLARER TECHNIQUES Declarer Techniques are separate, identifiable techniques for Planning and Play of a hand of Duplicate Bridge as the Declarer. Each is extensively defined and illustrated in this section and, in most cases, also has detailed Problems and Answers for extra learning by analysis. Declarer Techniques throughout the book are marked with an asterisk, as they are often referred to in other Techniques descriptions, and other sections of the book or related documents. An example is Discovery*. This means there is a Declarer Technique named “Discovery”, and it will be found in this Section. Its exact page number can be found in the Table of Contents. Declarer Techniques Table of Contents – next page Auxiliary Play Terms. Following the Table of Contents is a page of auxiliary terms. They don’t necessarily represent Declarer Techniques per se, but are language worthy of explanation: they can be synonyms, bridge slang, etc. If you come across a term in the reading that you don’t understand, look first in the Declarer Techniques, then in the Auxiliary Terms for a possible synonym. Pg. 1 ©Bob McConnell, 2014 Declarer Techniques DECLARER PLAY 2014 DECLARER TECHNIQUES Technique Page Advanced Play Planning – Multiple Choices – Advanced Split Odds 4 Blind Spot Avoidance 8 Break a New Suit 10 Blocking opponents play 12 Unblocking 14 Card Combinations (Also in “Basic Section”) 16 Counting 23 Cross Ruff 26 Dangerous Opponent (in Basic Section Only) - Dummy Reversal 31 Deception 34 Discovery