Challenges Within Florida's Gulf Coast Oyster Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Santa Fe New Mexican, 04-27-1901 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 4-27-1901 Santa Fe New Mexican, 04-27-1901 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 04-27-1901." (1901). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/1024 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SANTA FE NEW MEXICAN NO. 58 VOL. 38 SANTA FE, N. M., SATURDAY, APRIL 27, 1901. AN IMPORTANT ARREST. BRYAN'S FDTORE. ON FRIENDLY NOT THE OUR RELATIONS Rambler William Wilson Accused of the It is Discussed at Length By the Editor of FOOTING AGAIN Furnishing SHERIFF'S FAOLT CUBA Used WITH the Omaha Bee. Revolver and Ammunition New York, April 27. Edward Rose-wate- r, at the Penitentiary. editor of the Omaha. Bee, Is quo- For-- William alias MeGinty, has Sheriff Salome Garcia of Called Austria and Mexico Decide to , Wilson, Clayton, The Cuban Commission Upon ted iby the Times as saying last night: been arrested at Albuquerque upon a n, Answers An an pin-to- Each Other About the McFle Union County, President McKinley Today to "William Jennings Bryan, my give bench warrant Issued by Judge will Itae the candidate for governor ' Maximilian Affair, on the charge of having furnished the Important Question, Bid Him Farewell. -

A History of Oysters in Maine (1600S-1970S) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected]

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Darling Marine Center Historical Documents Darling Marine Center Historical Collections 3-2019 A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Lackovic, Randy, "A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s)" (2019). Darling Marine Center Historical Documents. 22. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents/22 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Darling Marine Center Historical Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) This is a history of oyster abundance in Maine, and the subsequent decline of oyster abundance. It is a history of oystering, oyster fisheries, and oyster commerce in Maine. It is a history of the transplanting of oysters to Maine, and experiments with oysters in Maine, and of oyster culture in Maine. This history takes place from the 1600s to the 1970s. 17th Century {}{}{}{} In early days, oysters were to be found in lavish abundance along all the Atlantic coast, though Ingersoll says it was at least a small number of oysters on the Gulf of Maine coast.86, 87 Champlain wrote that in 1604, "All the harbors, bays, and coasts from Chouacoet (Saco) are filled with every variety of fish. -

"He Beachcomber Is Rub

© All Advertisers "he Beachcomber is rub lished each Wed Looking into the a w w k mnv see. on clear days, the 3322 for advertis Isles of Shoals which are the historic islands located north- resentative cast of Hampton Beach. In 1660. six hundred fisher VOL. XXXVII, NO 2 Incorporating the men and their families lived •nfnr* A*p<h Advocolc WEDNESDAY, JUNE 30, 1965 on these islands. Then* are seven islands in this famous group The largest is Star Is- land where there is a hotel hich annual conferences of s Newest Port To Serve County at w Unitarian and Congregational churches are held. The world's newest port fa A former lighthouse keeper cility is located in Rocking on White's Island was the fa ham county at the mouth of ther of the famous American the Pi sea tai| 11a river in Ports poetess, Celia Thaxter. Most of mouth. her well known poems we**e Efforts begun in 1957 by a written at the Isles ot Shoals. group of interested business The best known is probably men became reality May 15 “The Little Sandpiper and 1”. Many ancient, wierd and of with the dedication of the first ten blood curdling stories are phase of the project, which of told of the islands. One story fers modern docks and load is that Captain Kidd buried and unloading facilities to mueh of his famous treasure large, ocean going ships. there. Some visitors, studying The impact of the project the crannies and crevices a- could be considerable if com mong the rocks, claim they can parable figures f l o m nearby still hear the “Old Pirate’s” Portland are any indication. -

THE PICTURESQUE in GIOVANNI VERGA's SICILIAN COLLECTIONS Jessica Turner Newth Greenfi

THE PICTURESQUE IN GIOVANNI VERGA’S SICILIAN COLLECTIONS Jessica Turner Newth Greenfield A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (Italian). Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Dr. Federico Luisetti Dr. Dino Cervigni Dr. Ennio Rao Dr. Amy Chambless Dr. Lucia Binotti ©2011 Jessica Turner Newth Greenfield ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JESSICA TURNER NEWTH GREENFIELD: The Picturesque in Giovanni Verga’s Sicilian Collections (Under the direction of Federico Luisetti) Giovanni Verga’s Sicilian short story collections are known for their realistic portrayal of the Sicilian peasant farmers and their daily struggles with poverty, hunger and injustice. This study examines the way in which the author employs the pictruresque in his Sicilian novelle and argues that there is an evolution in this treatment from picturesque to non-picturesque. Initially, this study will examine the elements and techniques that Verga uses to represent the picturesque and how that treatment changes and is utilized or actively destroyed as his writing progresses. For the purposes of this dissertation, a definition of the picturesque will be established and always associated with descriptions of nature. In this study, the picturesque will correspond to those descriptions of nature that prove pleasing for a painting. By looking at seven particular novelle in Vita dei campi and Novelle rusticane, I will show that Verga’s earlier stories are littered with picturesque elements. As the author’s mature writing style, verismo, develops, Verga moves through a transtitional phase and ultimately arrives at a non-picturesque portrayal of Sicily in his short stories. -

The Immigrant Oyster (Ostrea Gigas)

THE IMMIGRANT OYSTER (OSTREA GIGAS) NOW KNOWN AS THE PACIFIC OYSTER by E. N. STEELE PIONEER OLYMPIA OYSTERMAN IN COOPERATION WITH PACIFIC COAST OYSTER GROWERS ASSOCIATION, INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I.........................................................................................................................Page 1 INTRODUCTION AN OYSTER GOES ABROAD SEED SETTING IN MAYAGI PREFECTURE IN YEAR 1918 SEEDS WERE VERY SMALL IN YEAR 1919 STORY OF JOE MAYAGI AND EMY TSUKIMATO SAMISH BAY SELECTED FOR EXPERIMENTAL PLANTINGS FIRST PLANTING OF SEED WAS A SUCCESS EXPERIMENTAL WORK IN JAPAN REPORT BY DR. GALTSOFF (Doc. 1066) U. S. BIOLOGIST Dr. HORI, JAPANESE BIOLOGIST OFFICIAL) REPORT ON SEED IN 1919 LESSONS LEARNED FROM JAPANESE EXPERIENCE Time of year to ship--Small seed most successful- When and where planted required further experience -The oyster had to answer that question. A TRIP TO SAMISH BAY WASHINGTON STATE PASSED ANTI-ALIEN ACT IN 1921 ROCKPOINT OYSTER Co. COMPLETED PURCHASE MAY 18, 1923 CHAPTER II........................................................................................................................Page8 An Oyster becomes Naturalized-Haines Oyster Co. of Seattle First Customer -Development of Seattle Markets -First year marketing very limited -First year shipper, Emy Tsukimato from Japan -First Seed Shipment, 492 Cases. Samples still retained. Development of best type of cultch. Experimental shipping in hold of ship or on deck -expanding the markets. Advent of planting in Willapa Harbor and Grays Harbor - -

![Watch ]4Aker S Jeweler, OYSTERS](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3305/watch-4aker-s-jeweler-oysters-2913305.webp)

Watch ]4Aker S Jeweler, OYSTERS

YOL. 8. GRAND RAPIDS, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 7„ 1891. NO. 381. A l l e n D u k f e e . A . D. L e a v e n w o r t h . DAVIS’ CARBOLIC OIL STORE-KEEPIN’ ” FARMERS. mortgages and figures and interest and Allen Durfee & Co., Written for The Tradesman. sich ain’t wuth a cent. I’m afraid she* LINIMENT. Joseph Watson and George Holden won’t consent to put her name onto a D etroit, Mich. Gents—In 1856 I broke a knee-pan in the Prov were busy digging potatoes. It was fine mortgage. She says, ‘interest will eat idence, R. I., gymnasium, and ever since have September weather, and, their farms us up,’ that it’s like old Pundason’s FUNERAL DIRECTORS, been much troubled with severe pains in the knee joint. A few weeks ago I had a very severe joining each other, it was, perhaps, horse—eats nights as well as days.’ She 103 Ottawa St., Grand Rapids. attack of inflammatory rheumatism in the same knee, when I applied your Davis' Carbolic Oil natural that the neighbors had exchanged ays, ‘mebby you and Joe won’t do as Liniment, the third application of which cured work so that they might have a better well as them old store keepers in town’; W m. H. W hite & Co., me entirely. You have my permission to use my statements as you see fit. I am very thank opportunity to talk to each other. and she finds a great many excuses for MANUFACTURERS OF ful for the relief experienced. -

Rewilding the Islands: Nature, History, and Wilderness at Apostle

Rewilding the Islands: Nature, History, and Wilderness at Apostle Islands National Lakeshore by James W. Feldman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2004 © Copyright by James W. Feldman 2004 All Rights Reserved i For Chris ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii INTRODUCTION Wilderness and History 1 CHAPTER ONE Dalrymple’s Dream: The Process of Progress in the Chequamegon Bay 20 CHAPTER TWO Where Hemlock came before Pine: The Local Geography of the Chequamegon Bay Logging Industry 83 CHAPTER THREE Stability and Change in the Island Fishing Industry 155 CHAPTER FOUR Consuming the Islands: Tourism and the Economy of the Chequamegon Bay, 1855-1934 213 CHAPTER FIVE Creating the Sand Island Wilderness, 1880-1945 262 CHAPTER SIX A Tale of Two Parks: Rewilding the Islands, 1929-1970 310 CHAPTER SEVEN Conclusion: The Rewilding Dilemma 371 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 412 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS *** One of the chief advantages of studying environmental history is that you can go hiking, camping, and exploring in beautiful places and call it research. By choosing the history of the Apostle Islands for a dissertation topic, I even added kayaking and sailing to my list of research activities. There were many more hours spent in libraries, but those weren’t quite as memorable. All graduate students should have topics like this one. As I cast about for a dissertation topic, I knew that I wanted a place-based subject that met two requirements: It needed to be about a place to which I had a personal connection, and it needed to apply to a current, ongoing policy question or environmental issue. -

OYSTERS. •• Ps&A "F Assure Yon That I Am Frightful 1 1 Foot of Prospect Street/; ^';.^ Should Horrify You If I Uncovered My Mained Before Them, \Yhat Was Intend

X:~3"X*:KX.:^?||||* \ ?' ' ' •' ' * ,' "'-• ' • ">. ' ' -V ' '"•' ' -. ' •':•'• ' :.- -I V -'• f *-:;. -•>•;:••• •!; : Sv'; Vr . V';' v: - ;: vi -.jri-r v:^:/::^:-./;;,;.' ;--W: •%s MBM . -, &..^ ,\v:: •v.. --1 mmm m - '". " •"• ' ESTABLISHED 1880. THOMPSONVILLE, CONN., THURSDAY, JANUARY 26, 1899. VOL. XIX. NO. 39. GRANDMA'S FRIED CAKE. (The Gbompsonvtlle press. I'h, the day dawns on the prairie, and the dew Forbes & Wallace. is on the rose Published Every Thursday, by F. PARSONS, M. D„ E. PHYSICIAN AND SURGEON. ]n the dreamy time of boyhood, when an elfin TQa.® Parsons IF'xizrtin.g- Co., Residence and office No. 46 Pearl street, SPRINGFIELD, MASS., Jan. 26, 1899. bugle blows, Baking For a sweet eoul bud to hasten to where Thompsonville, - - Com. rhonipsonville, Conn. Office hours, 8.00 to 9.00 grandma likes to make TOO ». m.; 2.00 to 3.00, and 6.00 to 7.80 p. m. Order? Just the plumpest, 3ay be left at E. N. Smith's drug store. Tooth delighting, / POWDER THE PEESS is an eight column folio BAD to keep Sugar coated ABSOMJTEiyfevBE weekly, filled with interesting reading— f#-:- Xusic, Etc. Pried cake. New England, local and general news, The Mill-End Sale and well-selected miscellany. tie children Oh, the prairie hawk Is flying far beyond our Makes the food more delicious and wholesome TERMS: §1.50 a year in advance; six QENSLOW KING, visual sense! AT Oh, the beauteous colors dying just before star ROYAL BAKING POWDER CO., NEW YORK. months, 75 cents; three months, 40 cents at Teacher of the firmaments I Postage prepaid by the publishers. Oh, the bloom and bliss of boyhood, when the PIANO-FORTE, ORGAN PLAYING AND HARMONY Papers are forwarded until an explicit home FoiToes dz "Wallace's, grandmas like to make order is received by the publishers for Address P. -

Letters of Anton Chekhov to His Family and Friends, with Biographical Sketch

LETTERS OF ANTON CHEKHOV TO HIS FAMILY AND FRIENDS THE MACMILLAN COMPANY UBW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO • DAU.AS ATUCTTA • SAJ< FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., Uuttso LONDON • BOM BAT • CALCVTTA MELBOVaXB THE MACMILUO? CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO LETTERS OF ANTON CHEKHOV TO HIS FAMILY AND FRIENDS WITH BIOGR.\PHICAL SKETCH TR.A.NSL.4TED BY CONSTANCE GARNETT THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1920 A II rights reserved COPYKIGHT, 1920, BT THE MACMILLAN COMPANY Set up and printed. Published, February, 1920 TRANSLATOR'S NOTE Of the eighteen hundred and ninety letters published by Chekhov's family I have chosen for translation these letters and passages from letters which best to illustrate Chekhov's life, character and opinions. The brief memoir is abridged and adapted from the biographical sketch by his brother Mihail. Chekhov's letters to his wife after his mar- riage have not as yet been published. \ BIOGKAPIIICAL SKETCH In 1841 a serf belonging to a Russian nobleman pur- chased iiis freedom and the freedom of his family for 3,500 roubles, i)eing at the rate of 700 roubles a soul, with one daughter, Ahixandra, thrown in for nothing. The grandson of this serf was Anton Chekhov, the author; the son of the nobleman was Tcherlkov, the Tolstoyan and friend of Tolstoy. There is in this nothing striking to a Russian, but to the English student it is sufficiently signif- icant for several reasons. It illustrates how recent a growth was l\u) (jduealed middle-class in pre- revohitionary Russia, and it sliows, what is pi^rhaps more significant, the homogeneity of the; Russian people, and their capacity for comphitely changing their whole way of life. -

1578 1 1578 at HAMPTON COURT, Middlesex. Jan 1

1578 1578 At HAMPTON COURT, Middlesex. Jan 1, Wed New Year gifts. Among 201 gifts to the Queen: by Sir Gilbert Dethick, Garter King of Arms: ‘A Book of the States in King William Conqueror’s time’; by William Absolon, Master of the Savoy: ‘A Bible covered with cloth of gold garnished with silver and gilt and two plates with the Queen’s Arms’; by Petruccio Ubaldini: ‘Two pictures, the one of Judith and Holofernes, the other of Jula and Sectra’.NYG [Julia and Emperor Severus]. Jan 1: Henry Lyte dedicated to the Queen: ‘A New Herbal or History of Plants, wherein is contained the whole discourse and perfect description of all sorts of Herbs and Plants: their divers and sundry kinds: their strange Figures, Fashions, and Shapes: their Names, Natures, Operations and Virtues: and that not only of those which are here growing in this our Country of England, but of all others also of sovereign Realms, commonly used in Physick. First set forth in the Dutch or Almain tongue by that learned Dr Rembert Dodoens, Physician to the Emperor..Now first translated out of French into English by Henry Lyte Esquire’. ‘To the most High, Noble, and Renowned Princess, our most dread redoubtful Sovereign Lady Elizabeth...Two things have moved me...to offer the same unto your Majesty’s protection. The one was that most clear, amiable and cheerful countenance towards all learning and virtue, which on every side most brightly from your Royal person appearing, hath so inflamed and encouraged, not only me, to the love and admiration thereof, but all such others also, your Grace’s loyal subjects...that we think no travail too great, whereby we are in hope both to profit our Country, and to please so noble and loving a Princess...The other was that earnest and fervent desire that I have, and a long time have had, to show myself (by yielding some fruit of painful diligence) a thankful subject to so virtuous a Sovereign, and a fruitful member of so good a commonwealth’.. -

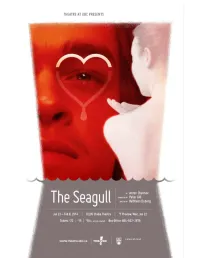

PRESS KIT - INDEX of CONTENTS

THE SEAGULL MEDIA CONTACT: Deb Pickman Marketing and Communications Specialist | UBC Department of Theatre and Film Phone 604 822 2769 | Cell 604 319 7656 | Fax 604 822 5985 [email protected] | http://www.theatrefilm.ubc.ca http://www.twitter.com/TheatreUBC | http://www.facebook.com/TheatreUBC https://twitter.com/FilmUBC | https://www.facebook.com/FilmUBC PRESS KIT - INDEX of CONTENTS Chekhov Factoids Quotes from The Seagull Anton Chekhov Quotes Anton Pavlovich Chekhov 1860 - 1904 Press Release Note: High resolution photos can be downloaded at http://www.theatre.ubc.ca/media_photos_seagull_2014.shtml Show Site: http://http://www.theatre.ubc.ca/seagull/index.html Chekhov Factoids Chekhov had a legion of friends, hangers-on and so many female admirers that the term "Antonovkas," was coined to describe them. The actual definition of an “Antonovaka” is: “Antonovka or Antonówka is a group of late-fall or early-winter apple cultivars with a strong acid flavor that have been popular in Russia as well as in Poland.” He had a pet mongoose named “Svoloch”. He is best known for his short stories and plays. He wrote 201 short stories. One of his literary maxims is that 'If a gun appears in the first act, it must be used by the third,' and remains a rule of literature to this day. Anton Chekhov has 266,619 likes on facebook and has a page dedicated to him with updated information everyday. https://www.facebook.com/ AntonChekhovAuthor He was friends with Russian writers, Leo Tolstoy and Maxim Gorky. Chekhov won the Pushkin Prize for "the best literary production distinguished by high artistic worth" in 1888. -

Reminiscences of Chekhov

Reminiscences of Chekhov M. Gorky, A. Kuprin, and I. A. Bunin Reminiscences of Chekhov Table of Contents Reminiscences of Chekhov.......................................................................................................................................1 M. Gorky, A. Kuprin, and I. A. Bunin...........................................................................................................2 Maxim Gorky..............................................................................................................................................................3 Alexander Kuprin......................................................................................................................................................10 I....................................................................................................................................................................11 II...................................................................................................................................................................13 III..................................................................................................................................................................15 IV.................................................................................................................................................................17 V...................................................................................................................................................................20