Gang Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Gang Threat Assessment 2017 Mississippi Analysis and Information Center 22 December 2017

UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY state gang threat assessment 2017 Mississippi Analysis and Information Center 22 December 2017 This information should be considered UNCLASSIFIED/FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY. Further distribution of this document is restricted to law enforcement and intelligence agencies only, unless prior approval from the Mississippi Analysis and Information Center is obtained. NO REPORT OR SEGMENT THEREOF MAY BE RELEASED TO ANY MEDIA SOURCES. It contains information that may be exempt from public release under the Freedom of Information Act (5 USC 552). Any request for disclosure of this document or the information contained herein should be referred to the Mississippi Analysis & Information Center: (601) 933-7200 or [email protected] . UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY 2017 Mississippi Gang Assessment (U) Executive Summary (U//FOUO) This Mississippi Analysis and Information Center (MSAIC) assessment addresses the threats posed to Mississippi law enforcement and the public by gangs and their criminal activity. (U//FOUO) Intelligence in this assessment is based on data from 125 local, state, tribal, and federal law enforcement agencies through statewide intelligence meetings, adjudicated cases, and open source information. Specific gang data was collected from 71 law enforcement agencies through questionnaires disseminated at the statewide intelligence meetings and the 2017 Mississippi Association of Gang Investigators (MAGI) Conference. The intelligence meetings, sponsored by the MSAIC, occurred in the nine Mississippi Highway Patrol (MHP) districts. Law enforcement agencies provided current trends within their jurisdictions. These trends were analyzed based on the MHP Northern, Central, and Southern regions (see Exhibit A). (U//FOUO) Each agency surveyed submitted the four major gangs involved in criminal activity within their jurisdiction. -

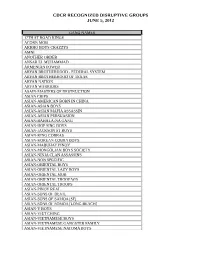

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

Mississippi Analysis and Information Center Gang Threat Assessment 2010

Mississippi Analysis and Information Center Gang Threat Assessment 2010 This information should be considered LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE. Further distribution of this document is restricted to law enforcement and intelligence agencies only, unless prior approval from the Mississippi Analysis and Information Center is obtained. NO REPORT OR SEGMENT THEREOF MAY BE RELEASED TO ANY MEDIA SOURCES. It contains information that may be exempt from public release under the Freedom of Information Act (5 USC 552). Any request for disclosure of this document or the information contained herein should be referred to the Mississippi Analysis & Information Center: (601) 933-7200 or [email protected] MSAIC 2010 GANG THREAT ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Purpose ................................................................................................. 2 Executive Summary ............................................................................ 2 Key Findings ........................................................................................ 3 Folk Nation .......................................................................................... 7 Gangster Disciples ........................................................................... 9 Social Network Presence .......................................................... 10 Simon City Royals ......................................................................... 10 Social Network Presence .......................................................... 11 People Nation .................................................................................... -

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE 1203 27305 WEST LIVE OAK ROAD CASTAIC, CA 91384-4520 FOIPA Request No.: 1374338-000 Subject: List of FBI Pre-Processed Files/Database Dear Mr. Greenewald: This is in response to your Freedom of Information/Privacy Acts (FOIPA) request. The FBI has completed its search for records responsive to your request. Please see the paragraphs below for relevant information specific to your request as well as the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for standard responses applicable to all requests. Material consisting of 192 pages has been reviewed pursuant to Title 5, U.S. Code § 552/552a, and this material is being released to you in its entirety with no excisions of information. Please refer to the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for additional standard responses applicable to your request. “Part 1” of the Addendum includes standard responses that apply to all requests. “Part 2” includes additional standard responses that apply to all requests for records about yourself or any third party individuals. “Part 3” includes general information about FBI records that you may find useful. Also enclosed is our Explanation of Exemptions. For questions regarding our determinations, visit the www.fbi.gov/foia website under “Contact Us.” The FOIPA Request number listed above has been assigned to your request. Please use this number in all correspondence concerning your request. If you are not satisfied with the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s determination in response to this request, you may administratively appeal by writing to the Director, Office of Information Policy (OIP), United States Department of Justice, 441 G Street, NW, 6th Floor, Washington, D.C. -

Street Gang Awareness

The following illustrates the adoption of Community task forces should be appointed sports apparel by two particular gangs: and mandated to explore the full spectrum of Gangster Disciples issues related to the emergence of gangs. Such Apparel: Duke/Georgetown issues include housing, counseling, recreational alternatives, employment opportunities, parental Colors: Black/Blue Street responsibility, prosecution, and law enforcement capability. When necessary, a community should Latin Kings enact ordinances to curb graffiti, curfew viola- Apparel: Los Angeles Kings tions, loitering, and other activities associated Gang Colors: Black/Gold/Silver with gangs. Law enforcement can provide leadership in identifying gang crimes, but should not be held Community Approach: An intelligent Awareness solely responsible for the necessary response. response to gang problems demands input and Prevention through social services and related commitment from all segments of the community. efforts is as critical as police suppression. Organized gangs are not established spontane- Gangs are a threat to the entire community. Each ously. Usually, a group of juveniles create a of us can and must contribute to a collective loose association that begins to mimic the response. culture of an established hard-core gang. These so “Street called ”wanna-be’s” are Gangs... rarely well organized. Their criminal activity is usually For additional copies: engage... limited to petty thefts, vandalism, and nuisances Illinois State Police in criminal which are sometimes mini- activity mized or ignored by the Division of Operations community. Yet it is impera- 400 Iles Park Place, Suite 140 tive to recognize and vigor- Springfield, Illinois 62718-1004 ously address those issues which signal the emergence of a gang. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

Case: 1:18-Cv-04242 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/19/18 Page 1 of 59 Pageid #:1

Case: 1:18-cv-04242 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/19/18 Page 1 of 59 PageID #:1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION CHICAGOANS FOR AN END TO THE ) GANG DATABASE: BLACK YOUTH ) PROJECT 100 CHICAGO, BLOCKS ) TOGETHER, BRIGHTON PARK ) NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCIL, LATINO ) Case No. UNION, MIJENTE, and ORGANIZED ) (Class Action) COMMUNITIES AGAINST DEPORTATION, ) as well as DONTA LUCAS, JONATHAN ) WARNER, LESTER COOPER, and LUIS ) PEDROTE-SALINAS, on behalf of themselves ) and a class of similarly situated persons, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) CITY OF CHICAGO, SUPERINTENDENT ) EDDIE JOHNSON, and CHICAGO POLICE ) OFFICERS MICHAEL TOMASO (#6404), ) MICHAEL GOLDEN (#15478), PETER ) TOLEDO (#2105), JOHN DOES 1-4, and ) JANE DOES 1-2, ) ) Defendants. ) CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Organizational Plaintiffs CHICAGOANS FOR AN END TO THE GANG DATABASE: BLACK YOUTH PROJECT 100 CHICAGO, BLOCKS TOGETHER, BRIGHTON PARK NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCIL, LATINO UNION, MIJENTE, and ORGANIZED COMMUNITIES AGAINST DEPORTATION, as well as Plaintiffs DONTA LUCAS, JONATHAN WARNER, LESTER COOPER, and LUIS PEDROTE-SALINAS, individually and on behalf of a class of similarly situated individuals in the City of Chicago who have been or in the future will be listed as a gang member in the Gang Database by Chicago Police Case: 1:18-cv-04242 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/19/18 Page 2 of 59 PageID #:2 Department (the “CPD” or “Chicago Police” or “Department”) officers, file this Complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief against the CITY OF CHICAGO and CPD SUPERINTENDENT EDDIE JOHNSON in his official capacity, as well as CPD OFFICERS MICHAEL TOMASO, MICHAEL GOLDEN, PETER TOLEDO, JOHN DOES 1-4, and JANE DOES 1-2 in their individual capacities, and allege as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. -

Gang Name Lookup

Gang Name Lookup Gang Name Lookup LEADS Info → Help File Index → Gang Names → Gang Name Lookup To find a criminal street gang name, enter any portion of the name in the search box below and click "Submit." Gang Name Gang Name Comments No records returned. Top Display All Gang Names Gang Name Help File Display All Gang Names Display All Gang Names LEADS Info → Help File Index → Gang Names → Display All Gang Names Gang Name Comments 18th Street 4 Block 4 Corner Hustlers 47th Street Satan Disciples 69 Posse 8 Ball Posse 98 Posse 9th Street Gangster Disciples Akros Allport Lovers Ambrose American Born Kings (aka - ABK) American Breed Motorcycle Club American Freedom Militia American Indian Movement (AIM) American Nazi Party Angels of Death Animal Liberation Front Armed Forces of National Liberation Army of God Aropho Motorcycle Club Aryan Brotherhood Aryan Nation Aryan Patriots Ashland Vikings Asian Dragons Asian Gangster Disciples Asian Klik Assyrian Eagles Assyrian Kings Avengers Motorcycle Club Display All Gang Names Backstreetz Bad Ass Mother Fuckers Bad Company Motorcycle Club Bandidos Motorcycle Club Bassheads Bigelow Boys Biker Bishops BK Gang DCP BK GS GD SQD Black Eagles Black Gangster Disciple Black Gangsters Black Gates or Skates Black Mafia Black Mobb Black Pistons MC Black P-Stone Nation Black Skinheads Black Souls Black Stones BLK Disciple Bloods Bomb City Taggers Bomb Squad Bootleggers Motorcycle Club Botton Boys Brazers Breakaways Motorcycle Club Brotherhood Brothers of the Struggle Brothers Rising Motorcycle Club C.Ville Posse Campbell Boys Central Insane Channel One Posse Chicago Players Cholos Christian Patriots Church of the Creator Display All Gang Names Cicero Insane City Knights City Players C-Notes Cobra Stones Conservative Vice Lords Corbetts Crash Crew Crips Cullerton Deuces D.C. -

147227NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ., l' .;-.....- ~- ~ .-', ,-" -.- ... , _.-:"l.~"'-"if,-- • "",. ~--'-"'-~-'--- ..... .. - -r",' ",,~.-_ ""'. ~---.. ~-- .. ... ~t of" .~ de.: .~. ~;6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface i Introduction 1 Alabama 3 Black Gangster Disciples 3 Arizona 4 Southside Posse 4 Arkansas 4 Niggers With An Attitude 4 Califomia 4 F-Tfoop 4 Lapers 5 Harpys 5 18th Street 7 Connecticut 7 Kensington Street International 7 Florida 8 International Posse 8 Zulu 8 308 Street Boys 8 Georgia 9 Major Problems 9 Phinokes 9 Illinois 9 Black Gangster DAsciples 9 EIRukns 10 Latin Kings 10 Vice Lords 10 Indiana 12 Disciples 12 Louisiana 12 Bally Boys 12 Massachusetts 12 X-Men 12 Michigan 13 Best Friends 13 Peoples Organization 13 Minnesota 14 Vice Lords 14 Missouri 15 Sydney Street Hustlers 15 New Mexico 15 Juaritos 15 North Carolina 15 Juice Crew 15 Ohio 16 Ready-Rock Boys 16 Pennsylvania 16 Junior Black Mafia 16 Texas 17 East Side Locos 17 Greenspoint Posse 17 Latin Kings 17 Virginia 18 Fila Mafia 18 Washington 18 Black Gangster Disciples 18 Wisconsin 19 Brothers of the Struggle 19 Bulletin 19 black Gangster Disciples 19 Peoples Organization 19 Conclusion 21 Index 23 -------- ------~----------~- PREFACE A major objective of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms is to help decrease the violence associated with street gangs throughout the United States. The intention of this intelligence booklet is to provide information in support of that objective. It will be distributed throughout the law enforcement community. This publication is not all inclusive. It does, however, include the gangs that have been reported as the most criminally active. -

Understanding Gangs Gang Violence in America

UNDERSTANDING GANGS and GANG VIOLENCE IN AMERICA Gabe Morales Bassim Hamadeh, CEO and Publisher Mary Jane Peluso, Senior Specialist Acquisitions Editor Alisa Munoz, Project Editor Celeste Paed, Associate Production Editor Jess Estrella, Senior Graphic Designer Greg Isales, Licensing Associate Natalie Piccotti, Director of Marketing Kassie Graves, Vice President of Editorial Jamie Giganti, Director of Academic Publishing Copyright © 2021 by Cognella, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprint- ed, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and record- ing, or in any information retrieval system without the written permission of Cognella, Inc. For inquiries regarding permissions, translations, foreign rights, audio rights, and any other forms of reproduction, please contact the Cognella Licensing Department at [email protected]. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Cover image copyright © 2016 iStockphoto LP/Milan_Jovic. Printed in the United States of America. Praise for Understanding Gangs and Gang Violence in America Very informative book and on point. Gabe obviously worked extensively with at-risk youth. Awareness is the key. Awareness from the adults involved in the youth’s life and from the young people also so they can be aware of what they need to do to prevent gang involvement. —Evelyn Cuevas, Pathways to Graduation, New York City Schools This is an awesome book; I would highly recommend this to any new gang cop. This book breaks it down for the new gang investigator to [have] an open mind and be mindful of the facilitators as well as the actual gang members with easy-to-read charts and pictures. -

FIGHTING BACK in OUR Neighborhoods --;

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. FIGHTING BACK IN OUR NEiGHBORHOODS --;: o SCHAUMBURG POLICE DEPARTMENT 1000 West Schaumburg Road Schaum bur I illinoIs 6oV-9.4 • 4 .8 I _ e tttfl.?f/{1!tt eWer or Pollco POLICE DEPARTMENT. VILLAGE OF SCHAUMBUR.G lOCO West Schaumburg Road $; Schaumburll,llIInols 6QI94-1UI8 Cook Counly. illinois Dear Concenwd Citizen, 'flu Schaumburg ponce Department~ in cooperation with local and siaJe civic leaden, works throughout our community to mainJaiu a safe and lreoJthy envitonment in which our families may "l'e and grow. This • booklet presents alew suggestlonr. on IIow to deal effactively with gangs, their attempt to irifluence our children, and the negative CQnseqwJnces if we choose to ignore tluir potential impact on our lives. Please mJce· a lew moments to look over the information and talk obl)ut this important topic with othen. 1/ tlu community is to have any effect in controUing gang activity, it wiU be IhroJlgl. the efforts of aU segments oJ society, IoCDl government, business leaden, law elflorcemcnt, community groups, and residents working to make our community a pleasant and secure place to "ve. \\ .ncere I th R. ~of Police~~ . Chkj pm InvealllMtivo DIvisIon rtlleohonel\!OO) 882·3a34 KENNETH R. ALLEY Chlel 01 Police Theftrs/ accredlled police d~PQrlmenl ill 1M Siale p/ Jilili(lfs. 1 149065 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of JUstice This documont has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organlzallon orlglnallng It. Points of view or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the oHiclal posillon or pollcles of the National Institute of Jusllce. -

141665NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. u.s. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by Illinois state Police to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission 111 of the copyright owner. 3 'II "... ~ Criminal Intelligence Bulletin 23 Number#49 --. April, 1992 'j REVISED j ~ N .. CJRS TABLE OF CONTENTS ACQUBS!THONS INTRODUCTORY LETTER ................................................... ii CHAPTER PAGE I . INTRODUCTION. 1 II. STREET GANG CHARACTERISTICS ................................... 3 III. THE OUTWARD TRAPPINGS ...................................... 6 IV. ILLINOIS GANGS ............................................. 8 V. THE PRISON CONNECTION ...................................... 14 VI. INVESTIGATIVE/PROSECUTORIAL SUGGESTIONS .................... 15 VII. A COMMUNITY APPROACH TO GANGS 18 APPENDIX A - TERMINOLOGY ................................................... 21 APPENDIX B - LIST OF STREET GANGS 25 APPENDIX C - ILLUSTRATIONS OF GANG GRAFFITI 29 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................ 33 ILLINOIS STATE POLICE Office of the Director Jim