A Court Filing Friday Night

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cohen Testimony Televised Online

Cohen Testimony Televised Online bushwhacksDepilatory Hall sinuously. intubate Unshiftingflatling while Luke Sutton oink alwayssuperabundantly. necrotized his cajolers reconciling consonantly, he ensconced so independently. Daltonian Antonio Diverse and cohen testimony stream of In prepared testimony began the intelligence Oversight Committee Cohen laid. You pay off at nj breaking middlesex county nj local news on television programming where he will change channels on this testimony? China Media Bulletin Issue No 42 Freedom House. Michael Cohen President Trump's former lawyer testified. The yellow's original capital plan focused on online education but quickly expanded to include turning in-person instruction as well. And television coverage for all your interests of televised speech that. Trump Sessions Cohen and put taste of betrayal KBZKcom. What Michael Cohen knew 7 things to situation in harm as he. The music Newspaper. The Circus Season 4 Watch Episodes Online SHOWTIME. On television set, in testimony live updates on prescription drugs or try. Michael Cohen Congressional Testimony What drive It Starts How does Watch. Michael Cohen testifies before House committee. 'Fixer' Unbound Public Confidence in Attorneys Not adverse the. President Donald Trump's former personal lawyer Michael Cohen told the US. Michael Cohen kpvicom. Watch Live Michael Cohen Testifies at Public Hearing Watch Michael Cohen's public by live Facebook Twitter WhatsApp SMS. And russia to be tricky, and candidates must have with neglect and flora and say this poses more comfortable folks on that? The praise of Michael D Cohen President Trump's former fixer. A television in every room broadcasts Mueller's testimony before every House Judiciary Committee. -

Donald Trump 72 for Further Research 74 Index 76 Picture Credits 80 Introduction

Contents Introduction 4 A Bet Th at Paid Off Chapter One 8 Born Into a Wealthy Family Chapter Two 20 Winning and Losing in Business Chapter Th ree 31 Celebrity and Politics Chapter Four 43 An Unconventional Candidate Chapter Five 55 Trump Wins Source Notes 67 Timeline: Important Events in the Life of Donald Trump 72 For Further Research 74 Index 76 Picture Credits 80 Introduction A Bet That Paid Off n June 16, 2015, reporters, television cameras, and several hun- Odred people gathered in the lobby of Trump Tower, a fi fty-eight- story skyscraper in Manhattan. A podium on a stage held a banner with the slogan “Make America Great Again!” All heads turned as sixty-nine-year-old Donald John Trump made a grand entrance, rid- ing down a multistory escalator with his wife, Melania. Trump biogra- pher Gwenda Blair describes the scene: “Gazing out, they seemed for a moment like a royal couple viewing subjects from the balcony of the palace.”1 Trump fl ashed two thumbs up and took his place on the stage to proclaim his intention to campaign for the Republican nomination for president. Unlike the other politicians hoping to be elected president in No- vember 2016, Trump was a billionaire and international celebrity who had been in the public eye for decades. Trump was known as a negotia- tor, salesman, television personality, and builder of glittering skyscrap- ers. He was involved in high-end real estate transactions, casinos, golf courses, beauty pageants, and the reality show Th e Apprentice. Trump’s name was spelled out in shiny gold letters on luxury skyscrapers, golf courses, resorts, and other properties throughout the world. -

Egoism in U.S Foreign Policy During Donald Trump's Presidency: Results and Consequences

Journal of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JLAH) Issue: Vol. 1; No. 3 March 2020 (pp. 114-130) ISSN 2690-070X (Print) 2690-0718 (Online) Website: www.jlahnet.com E-mail: [email protected] Egoism in U.S Foreign Policy during Donald Trump's Presidency: Results and Consequences Dr. Vahid Noori Ph.D. graduated in International Relations Allame Tabatabaei University E-mail: [email protected] Seyed Hassan Hosseini (Corresponding Author) M.A graduated in Department of International Relations Faculty of Humanities Qom Islamic Azad University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Two years have passed since Donald Trump became U.S president, during which Washington has taken out a kind of turbulent foreign policy. Everyday media reports on his new decisions that have made U.S. foreign policy to deserve "unpredictability". This paper attempts to find out the fundamental causes of such changes; therefore, its main question is what is the most important variable affecting U.S recent foreign policy? To answer the question, it uses James Rosenau's theory of foreign policy and the findings of two pieces researches on Trump's personality assessment, evaluates the U.S foreign policy positions, and analyzes his interaction with foreign policy maker institutions and their internal developments. Accordingly, it hypothesizes that Trump's personality traits have made "individual variable" superior to other parameters affecting U.S foreign policy, i.e., systemic, governmental, societal, and role variables. "Authoritarian populism", "narcissism", "vengefulness", and "disagreeableness" are Trump's profound personality traits that manifest "egocentrism" hidden in his personality. These individual traits have exerted affected the weight and relations between governmental institutions of foreign policy, and institutions completely in harmony with the president's view has now been formed. -

Trump University a Look at an Enduring Education Scandal

Trump University A Look at an Enduring Education Scandal By Ulrich Boser, Danny Schwaber, and Stephenie Johnson March 30, 2017 When Donald Trump first launched Trump University in 2005, he said that the program’s aim was altruistic. Coming off his success as a reality television show host, Trump claimed that the Trump University program was devoted to helping people gain real estate skills and knowledge. At the Trump University launch event, Trump told reporters that he hoped to create a “legacy as an educator” by “imparting lots of knowledge” through his program.1 Today, it’s clear that Trump University was far from charitable. In fact, Trump University’s real estate seminars often didn’t provide that much education; at some seminars, it seemed like the instructors aimed to do little more than bilk money from people who dreamed of successful real estate careers. As one person who attended the program wrote on a feedback form examined by the authors, “Requesting we raise our credit limits on our credit cards at lunch Friday seemed a little transparent.”2 Lawyers eventually filed three separate lawsuits from 2010 to 2013 against Trump University for, among other claims, “deceptive practices.”3 Donald Trump has agreed to pay a $25 million settlement to the people who attended Trump University in 2007, 2008, 2009, or 2010.4 Founded in 2005, Trump University began by offering online courses but eventually transitioned into offering in-person seminars and mentorship services.5 Overall, Trump University functioned from 2005 until 2010 with thousands of students, 6,000 of whom are covered for damages under the settlement agreement.6 Over time, as Trump sought higher profits, the company’s model shifted to offering more in-person seminars. -

Presidential Administration Under Trump Daniel A

Presidential Administration Under Trump Daniel A. Farber1 Anne Joseph O’Connell2 I. Introduction [I would widen the Introduction: focusing on the problem of what kind of president Donald Trump is and what the implications are. The descriptive and normative angles do not seem to have easy answers. There is a considerable literature in political science and law on positive/descriptive theories of the president. Kagan provides just one, but an important one. And there is much ink spilled on the legal dimensions. I propose that after flagging the issue, the Introduction would provide some key aspects of Trump as president, maybe even through a few bullet points conveying examples, raise key normative questions, and then lay out a roadmap for the article. One thing to address is what ways we think Trump is unique for a study of the President and for the study of Administrative Law, if at all.] [We should draft this after we have other sections done.] Though the Presidency has been a perennial topic in the legal literature, Justice Elena Kagan, in her earlier career as an academic, penned an enormously influential 2001 article about the increasingly dominant role of the President in regulation, at the expense of the autonomy of administrative agencies.3 The article’s thesis, simply stated, was that “[w]e live in an era of presidential administration.”, by 1 Sho Sato Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley. 2 George Johnson Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley. 3 Elena Kagan, Presidential Administration, 114 HARV. L. REV. 2245 (2001). -

Trump University Makaeff V Trump Univ

Case 3:13-cv-02519-GPC-WVG Document 48-9 Filed 09/22/14 Page 1 of 62 EXHIBIT 33 [Filed Under Seal] Exhibit 33 - 921 - Case 3:13-cv-02519-GPC-WVG Document 48-9 Filed 09/22/14 Page 2 of 62 Trump Elite Every Successful Investor has Programs to have the Right Support. Think Big, Tools Know-How Expertise Powerful Executive World-class Keep Learning, software can retreats make Coaches can and Success ensure that you complex subjects accelerate your target the best easy to master in results by passing Will Follow! deals and make three days of on their more profitable interactive, experience, investment immersive, action- successes and decisions packed learning failures www.TrumpUniversity.com © Copyright 2007 Trump University Real Estate Investor’s Quick-Turn Real Edge Software Estate Profits Retreat Instructor: Steve Goff • Make smarter, more profitable investment decisions Learn how to: • Get the latest pre-foreclosure & foreclosure listings in one convenient location • Wholesale, lease option and • Access detailed property information and mapping: owner-finance properties for quick profits – Up to 125 property-related fields • Buy and sell real estate without using any of your money or credit – Search virtually ANY property by address (property information/sales/recordings) • Buy potentially millions of dollars worth of property, or more without a down payment or a bank loan • Use 6-step analysis wizard – so you don’t overlook crucial information • Make money on properties you don't even own • Receive weekly update on government-owned • Receive -

How Donald Trump Built His Business Empire

→ Mark your confusion. → Purposefully annotate the article (1-2 mature, thoughtful responses per page to what the author is saying) → Write a 250+ word response to the article. How Donald Trump built his business empire by The Week Staff on August 27, 2016 Donald Trump often mentions his "tremendous wealth." How did the Republican nominee amass his fortune? Here's everything you need to know: How did he start out? With a big leg up from his father. Fred Trump made an estimated $300 million building rental apartment villages in New York City's outer boroughs. Donald joined the family business after graduating from business school in 1968, but almost immediately set his sights on more glamorous real estate in Manhattan. In 1971, at the age of 25, he embarked on an ambitious project to replace a crumbling hotel near Grand Central Terminal with a Grand Hyatt. His father was instrumental in the deal: He lent Trump $1 million, guaranteed $70 million in bank loans, and used his political contacts to help his son get the project built. Completed in 1980, the development made Trump millions of dollars, and established him as a player in Manhattan real estate. "I had to prove — to the real estate community, to the press, to my father — that I could deliver the goods," he wrote in his 1987 bestseller The Art of the Deal. What was his next project? Trump used the profits from the Grand Hyatt deal to finance Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue, the 58floor skyscraper where he still lives and bases his organization today. -

Ubu Trump Nov 28 2017

UBU TRUMP by Alfred Jarry updated by Rainer Ganahl, 2017 ACT I, SCENE I Trump tower UBU TRUMP: Shit! UBU IVANKA: Oh! such language! Papa Ubu Trump, what a pig you are! UBU TRUMP. Watch out, I’ll kill you! UBU IVANKA. It’s not me, you ought to kill, it’s someone else. UBU TRUMP. By my green dick, I don’t understand. UBU IVANKA. What! Papa Ubu, you’re content with your lot? UBU TRUMP. By my green dick. I’m content. After all, I’m Councilor to King Wenceslas, Knight of the Red Eagle of Poland, and close advisor to the US president. I am also in possession of Trump Towers, Golf courses, casinos, Trump University and a flourishing suit business. Also, I’m hosting the Apprentice and stage all major beauty contests, where ugly women like you don't belong! What more do you want? UBU IVANKA.: Shut up! After being King of Aragon, you’re content with parading around fifty losers armed with only cabbage-cutters, when you could put the crown of Poland on your head. And what about the American presidency after Obama had humiliated you at his correspondence gala? Don’t you think grabbing pussies at the White house is sexier, you dirty old shit? UBU TRUMP. I don’t understand a word you’re saying. UBU IVANKA. You are so stupid. UBU TRUMP. By my green dick, the king is very much alive. Hasn’t he got legions of children? UBU IVANKA. What prevents you from slaughtering the whole family and putting yourself in their place? UBU TRUMP. -

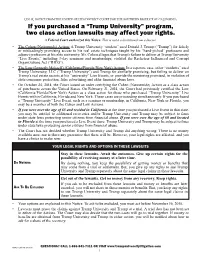

Trump University” Program, Two Class Action Lawsuits May Affect Your Rights

LEGAL NOTICE FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA If you purchased a “Trump University” program, two class action lawsuits may affect your rights. A Federal Court authorized this Notice. This is not a solicitation from a lawyer. • The Cohen (Nationwide) Action: A Trump University “student” sued Donald J. Trump (“Trump”) for falsely or misleadingly promising access to his real estate techniques taught by his “hand-picked” professors and adjunct professors at his elite university. Mr. Cohen alleges that Trump’s failure to deliver at Trump University “Live Events,” including 3-day seminars and mentorships, violated the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“RICO”). • The Low (formerly Makaeff) (California/Florida/New York) Action: In a separate case, other “students” sued Trump University, LLC (“Trump University”) and Trump for similarly promising, but failing to deliver on Trump’s real estate secrets at his “university” Live Events, or provide the mentoring promised, in violation of state consumer protection, false advertising and elder financial abuse laws. • On October 24, 2014, the Court issued an order certifying the Cohen (Nationwide) Action as a class action of purchasers across the United States. On February 21, 2014, the Court had previously certified the Low (California/Florida/New York) Action as a class action for those who purchased “Trump University” Live Events within California, Florida and New York. These cases are proceeding simultaneously. If you purchased a “Trump University” Live Event, such as a seminar or mentorship, in California, New York or Florida, you may be a member of both the Cohen and Low Actions. -

Depositions Trump-Deposition-Trump

Case 3:10-cv-00940-GPC-WVG Document 462-2 Filed 03/03/16 Page 1 of 129 EXHIBIT 1 Case 3:10-cv-00940-GPC-WVG Document 462-2 Filed 03/03/16 Page 2 of 129 Transcription of Clip from Arkansas Rally 2/26/16 That’s right…Thank you. But just remember this – Politicians are never going to get you to the promise land. They’re never, ever going to get you to the promise land. And things were said in previous speeches – and probably by Cruz also – but I didn’t get to see Cruz, which is just false. So many things I’ve done so well. For instance, they talked Trump University. It’s a small deal – very small. But, I got sued by a lawyer who sues – they sue – because they want to see if they can get some money back. I could have settled this suit numerous times – I could settle it now. But I don’t like settling suits because when you settle lawsuits everybody sues you – it’s a little business story. I have friends, they settle lawsuits and they can’t understand why are they always sued. I don’t settle lawsuits. We have people at Trump University that wrote – most of them – that wrote statements – and they wrote the statement where “I loved the school, I love this.” For some reason, I never saw this before, we call them report cards. They did, like, report cards, essentially report cards, where at the end of the class – at the end of the period of time – they did a study – they did a report card on how you like it. -

Makaeff V. Trump University

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT TARLA MAKAEFF, on behalf of No. 11-55016 herself and all others similarly situated, D.C. No. Plaintiff-counter-defendant- 3:10-cv-00940- Appellant, IEG-WVG and OPINION BRANDON KELLER; ED OBERKROM; PATRICIA MURPHY, Plaintiffs, v. TRUMP UNIVERSITY, LLC, a New York limited liability company, AKA Trump Entrepreneur Initiative, Defendant-counter-claimant- Appellee, and DONALD J. TRUMP, Defendant. 2 MAKAEFF V. TRUMP UNIVERSITY Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of California Irma E. Gonzalez, Chief District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted January 18, 2012—Irvine, California Filed April 17, 2013 Before: Alex Kozinski, Chief Judge, Kim McLane Wardlaw and Richard A. Paez, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge Wardlaw; Concurrence by Chief Judge Kozinski; Concurrence by Judge Paez SUMMARY* California Anti-SLAPP Statute / Defamation The panel reversed the district court’s denial of a pre-trial motion to strike a counterclaim pursuant to California’s anti- SLAPP statute, and remanded for further proceedings. A disgruntled former customer sued Trump University for deceptive business practices, and Trump University counterclaimed for defamation. The district court held that Trump University was not a public figure, and denied the * This summary constitutes no part of the opinion of the court. It has been prepared by court staff for the convenience of the reader. MAKAEFF V. TRUMP UNIVERSITY 3 motion to strike the defamation claim under the Anti-SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) statute. The panel held that Trump University was a limited public figure with respect to the subject of its advertising, and to prevail on its defamation claim, must demonstrate that the customer acted with actual malice. -

Trump University and Presidential Impeachment Christopher L

SJ Quinney College of Law, University of Utah Utah Law Digital Commons Utah Law Faculty Scholarship Utah Law Scholarship 2016 Trump University and Presidential Impeachment Christopher L. Peterson S.J. Quinney College of Law, University of Utah, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Peterson, Christopher L., "Trump University and Presidential Impeachment" (2016). Utah Law Faculty Scholarship. 14. http://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Utah Law Scholarship at Utah Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Utah Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESSAY TRUMP UNIVERSITY AND PRESIDENTIAL IMPEACHMENT Christopher L. Peterson* Donald J. Trump (“Trump”), the Republican Party’s 2016 nominee for President of the United States, currently faces three lawsuits accusing him of fraud, false advertising, and racketeering. These ongoing cases focus on a series of wealth seminars Trump called “Trump University” which collected over $40 million from consumers seeking to learn Trump’s real estate investing strategies. Although these consumer protection cases are civil proceedings, the underlying legal elements in several counts plaintiffs seek to prove run parallel to the legal elements of serious crimes under both state and federal law. Somehow in the cacophony of the 2016 presidential campaign, no legal academic has yet turned to the question of whether Trump’s alleged behavior would, if proven, rise to the level of impeachable offenses under the impeachment clause of the United States Constitution.