The History of British Cartoons and Caricature Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Major Exhibition of Stage Designs by Celebrated Cartoonist Gerald Scarfe

Gerald Scarfe: Stage and Screen At House of Illustration’s Main Gallery 22 September 2017 – 21 January 2018 The first major exhibition of stage designs by celebrated cartoonist Gerald Scarfe “I always want to bring my creations to life – to bring them off the page and give them flesh and blood, movement and drama.” – Gerald Scarfe "There is more to him than journalism... his elegantly grotesque, ferocious style remains instantly recognisable" – Evening Standard feature 20/09/17 Critics Choice – Financial Times 16/09/17 On 22 September 2017 House of Illustration opened the first major show of Gerald Scarfe’s striking production designs for theatre, rock, opera, ballet and film, many of which are being publicly exhibited for the very first time. Gerald Scarfe is the UK’s most celebrated political cartoonist; his 50-year-long career at The Sunday Times revealed an imagination that is acerbic, explosive and unmistakable. But less well known is Scarfe’s lifelong contribution to the performing arts and his hugely significant work beyond the page, designing some of the most high-profile productions of the last 30 years. This exhibition is the first to explore Scarfe’s extraordinary work for stage and screen. It features over 100 works including preliminary sketches, storyboards, set designs, photographs, ephemera and costumes from productions including Orpheus in the Underworld at English National Opera, The Nutcracker by English National Ballet and Los Angeles Opera’s The Magic Flute. It also shows his 1994 work as the only ever external Production Designer for Disney, for their feature film Hercules, as well as his concept, character and animation designs for Pink Floyd’s 1982 film adaptation of The Wall. -

Martinrowson.Pdf

Martin Rowson on Free Speech and Cartoons Nigel Warburton: Martin Rowson is a satirical cartoonist. I asked him about free speech, cartoons, and causing offence. Don’t listen to this podcast if you are offended by swearing. Nigel Warburton: Michael Rowson, welcome to Free Speech Bites. Michael Rowson: Hello. Nigel Warburton: The topic we're going to focus on is free speech and cartoons. I wonder if you could begin by saying something about your own work as a cartoonist. Michael Rowson: I suppose I have a bit of a reputation for being one of the more hard- hitting Lefty cartoonists, and I'm very fortunate - this isn't just brown-nosing - to work for the Guardian who tolerate that kind of thing from me and Steve Bell, although sometimes I think they don't notice until it's too late. I see myself, very proudly actually, as part of a uniquely British tradition. We are, as a country, the only country in the world that has had over 300 years of tolerated visual satire, which hasn't been subjected to the kind of constraints it has in other countries around the world, which is why, since the advent of the Internet, when Steve and I have had our work available to a global audience, we have had such visceral responses from people who are just not used to this kind of thing. As soon as they started putting our work on the Guardian website and the Guardian website took off in America, the traffic of hate mail, hate email, from America, was quite extraordinary, quite deliberately targeted. -

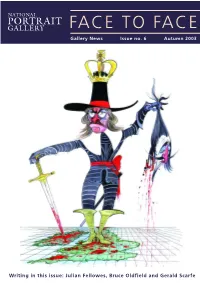

FACE to FACE Gallery News Issue No

P FACE TO FACE Gallery News Issue no. 6 Autumn 2003 Writing in this issue: Julian Fellowes, Bruce Oldfield and Gerald Scarfe FROM THE DIRECTOR The autumn exhibition Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits offers an unusual opportunity to see fascinating images of those who usually remain invisible. The exhibition offers intriguing stories of the particular individuals at the centre of great houses, colleges or business institutions and reveals the admiration and affection that caused the commissioning of a portrait or photograph. We are also celebrating the completion of the new scheme for Trafalgar Square with the young people’s education project and exhibition, Circling the Square, which features photographs that record the moments when the Square has acted as a touchstone in history – politicians, activists, philosophers and film stars have all been photographed in the Square. Photographic portraits also feature in the DJs display in the Bookshop Gallery, the Terry O’Neill display in the Balcony Gallery and the Schweppes Photographic Portrait Prize launched in November in the Porter Gallery. Gerald Scarfe’s rather particular view of the men and women selected for the Portrait Gallery is published at the end of September. Heroes & Villains, is a light hearted and occasionally outrageous view of those who have made history, from Elizabeth I and Oliver Cromwell to Delia Smith and George Best. The Gallery is very grateful for the support of all of its Patrons and Members – please do encourage others to become Members and enjoy an association with us, or consider becoming a Patron, giving significant extra help to the Gallery’s work and joining a special circle of supporters. -

The Illustrated Winespeak Free

FREE THE ILLUSTRATED WINESPEAK PDF Ronald Searle | 104 pages | 01 Jun 1994 | Souvenir Press Ltd | 9780285625921 | English | London, United Kingdom The Illustrated Winespeak: Ronald Searle's Wicked World of Winetasting by Ronald Searle Please sign in to write a review. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will update your details. Would you like to proceed to the App store to download the Waterstones App? We have recently updated our Privacy Policy. The Illustrated Winespeak site uses cookies The Illustrated Winespeak offer you a better experience. By continuing to browse the site you accept our Cookie Policy, you can change your settings at any time. In stock Usually dispatched within 24 hours. Quantity Add to basket. This item has been added to your basket View basket Checkout. Your local Waterstones may have stock of this item. On The Illustrated Winespeak's first publication inthis hilarious send-up of winetaster's jargon was hailed by 'The Financial Times' as "one of this year's bubbling successes". It has since been constantly reprinted to meet demand and has become a classic of The Illustrated Winespeak kind. For all those mystified by the strange pontifications of wine-buffs, Ronald Searle's The Illustrated Winespeak is the perfect guide to the meaning behind "distinctive nose", "full bodied" and "elegant but lacks backbone". The book is an onslaught on the pretentious nonsense written and spoken about wine. His interpretations of such apparently innocent phrases as 'full bodied' and 'distinctive nose' The Illustrated Winespeak certainly make you laugh aloud, and in all probability splutter in your wine glass. -

British Library Conference Centre

The Fifth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference 18 – 20 July 2014 British Library Conference Centre In partnership with Studies in Comics and the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics Production and Institution (Friday 18 July 2014) Opening address from British Library exhibition curator Paul Gravett (Escape, Comica) Keynote talk from Pascal Lefèvre (LUCA School of Arts, Belgium): The Gatekeeping at Two Main Belgian Comics Publishers, Dupuis and Lombard, at a Time of Transition Evening event with Posy Simmonds (Tamara Drewe, Gemma Bovary) and Steve Bell (Maggie’s Farm, Lord God Almighty) Sedition and Anarchy (Saturday 19 July 2014) Keynote talk from Scott Bukatman (Stanford University, USA): The Problem of Appearance in Goya’s Los Capichos, and Mignola’s Hellboy Guest speakers Mike Carey (Lucifer, The Unwritten, The Girl With All The Gifts), David Baillie (2000AD, Judge Dredd, Portal666) and Mike Perkins (Captain America, The Stand) Comics, Culture and Education (Sunday 20 July 2014) Talk from Ariel Kahn (Roehampton University, London): Sex, Death and Surrealism: A Lacanian Reading of the Short Fiction of Koren Shadmi and Rutu Modan Roundtable discussion on the future of comics scholarship and institutional support 2 SCHEDULE 3 FRIDAY 18 JULY 2014 PRODUCTION AND INSTITUTION 09.00-09.30 Registration 09.30-10.00 Welcome (Auditorium) Kristian Jensen and Adrian Edwards, British Library 10.00-10.30 Opening Speech (Auditorium) Paul Gravett, Comica 10.30-11.30 Keynote Address (Auditorium) Pascal Lefèvre – The Gatekeeping at -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 92 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #376 ORIGINAL ART BY GISELLA LOEFFLER #115 - 1826 Anti-Slavery #289 - Paul Hosch (Swiss) Picture Books #386 - Little Nemo in Slumberland Printer Proof #291 - German Art Nouveau Picture Book Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON TUCK CLOTH BIRD ABC OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. THIS IS TO 5. ABC. (BIRDS) BIRDS ABC [ABC OF BIRDS on title]. London: Raphael Tuck 1899. 160 (4 1/2 x 6 3/4”), pictorial cloth, light shelf wear, VG+. -

Humour and Caricature Teachers Notes Humour and Caricature

Humour and Caricature Teachers Notes Humour and Caricature “We all love a good political cartoon. Whether we agree with the underlying sentiment or not, the biting wit and the sharp insight of a well-crafted caricature and its punch line are always deeply satisfying.” Peter Greste, Australian Journalist, Behind the Lines 2015 Foreward POINTS FOR DISCUSSION: Consider the meaning of the phrases “biting wit”, “sharp insight”, “well-crafted caricature”. Look up definitions if required. Do you agree with Peter Greste that people find political cartoons “deeply satisfying” even if they don’t agree with the cartoons underlying sentiment? Why/why not? 2 Humour and Caricature What’s so funny? Humour is an important part of most political cartoons. It’s a very effective way for The joke cartoonists to communicate their message to their audience can be simple or — and thereby help shape public opinion. multi-layered and complex. POINTS FOR DISCUSSION: “By distilling political arguments and criticisms into Do a quick exercise with your classmates — share a couple clear, easily digestible (and at times grossly caricatured) of jokes. Does everyone understand them? Why/why not? statements, they have oiled our political debate and What does this tell us about humour? helped shape public opinion”. Peter Greste, Australian Journalist, Behind the Lines foreward, http://behindthelines.moadoph.gov.au/2015/foreword. Why do you believe it’s important for cartoonists to make their cartoons easy to understand? What are some limitations readers could encounter which may hinder their understanding of the overall message? 3 Humour and Caricature Types of humour Cartoonists use different kinds of humour to communicate their message — the most common are irony, satire and sarcasm. -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Adam Dant 'The Government Stable'

ADAM DANT ‘THE GOVERNMENT STABLE’ 2015 GENERAL ELECTION ARTWORK – A KEY TO THE DRAWING ADAM DANT ‘THE GOVERNMENT STABLE’ 2015 GENERAL ELECTION ARTWORK Places: 1. Leeds Town Hall: The Victorian Civic architectural splendor of Leeds Town Hall was the venue for the BBC’s final leadership orations. The ceiling and arches are decorated with the logos of the UK political parties. 2. Central Methodist Hall, Westminster: The clock and pipe organ are from the Central Methodist Hall where the BBC’s ‘Challengers’ Debate’ took place. At 10pm the clock marks the time that polling stations across the UK closed and voting ended. 3. Swindon University Technical College Water Tower and Courtyard Pavement: Venue for The Conservative Party Manifesto Launch; the college occupies Swindon’s former Railway Village. 4. Testbed 1 Nightclub Battersea: Hanging from the ceiling are glow-stick lights from the trendy, power-cut-hit, Liberal Democrat Manifesto launch venue. Panels on the ceiling are decorated with the Lib Dem’s backdrop of children’s hand prints. 5. Arcellor Mittal Tower, Queen Elizabeth ll Olympic Park: The Labour Party Election Campaign launch took place in the viewing gallery of the Mittal tower. The party leader was introduced by an NHS nurse entering through a receiving line of cheering Labour Student activists. 6. Escalators from UKIP’s poster on immigration policy. 7. Rahere Climbing Centre, Edinburgh: Vertiginous, hand hold studded climbing walls provided the backdrop to the Scottish National party Manifesto launch. 8. The White Cliffs of Dover: The United Kingdom Independence Party unveiled a campaign poster depicting three escalators traveling up the White Cliffs of Dover at The Coastguard Inn, St Margaret’s with the cliffs the English Channel and France Telecom on everyone’s mobile phones as a backdrop. -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

Copyright Acknowledgement Booklet

Copyright Acknowledgement Booklet For the January 2013 exam series This booklet contains the acknowledgements for third-party copyright material used in OCR assessment materials for 14 – 19 Qualifications. www.ocr.org.uk About the Copyright Acknowledgement Booklet Prior to the June 2009 examination series, acknowledgements for third-party copyright material were printed on the back page of the relevant exam papers and associated assessment materials. For security purposes, from that series onwards, OCR has created this separate booklet to put all of the acknowledgements, rather than including them in the exam papers or associated assessment materials. The booklet is published after each examination series, as soon as the assessment materials become available to the public. It is available online from the OCR website at: http://www.ocr.org.uk/i-want-to/prepare-and-practise/past-papers-finder/ The OCR Copyright Team can be contacted by post at 1 Hills Road, Cambridge, CB1 2EU, or by email at [email protected]. Where possible, OCR has sought and cleared permission to reproduce items of third-party owned copyright material. Every reasonable effort has been made by OCR to trace copyright holders, but if any items requiring clearance have unwittingly been included, please contact the Copyright Team at the addresses above and OCR will be pleased to make amends at the earliest possible opportunity. How to find an acknowledgement Each acknowledgement is filed firstly by subject and then under the unit number of the exam paper in which the copyright material appears. Where an exam paper has more than one document associated with it, each document is identified with its separate acknowledgements. -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body.