Creating the Miss Porter's School Digital Archive Deborah Smith Kent State University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King's Academy

KING’S ACADEMY Madaba, Jordan Associate Head of School for Advancement August 2018 www.kingsacademy.edu.jo/ The Position King’s Academy in Jordan is the realization of King Abdullah’s vision to bring quality independent boarding school education to the Levant as a means of educating the next generation of regional and global leaders and building international collaboration, peace, and understanding. Enrolling 670 students in grades 7-12, King’s Academy offers an educational experience unique in the Middle East—one that emulates the college-preparatory model of American boarding schools while at the same time upholding and honoring a distinctive MISSION Middle Eastern identity. Since the School’s founding in 2007, students from Jordan, throughout the Middle East, and other In a setting that is rich in history nations from around the world have found academic challenge and tradition, King’s Academy and holistic development through King’s Academy’s ambitious is committed to providing academic and co-curricular program, which balances their a comprehensive college- intellectual, physical, creative, and social development. preparatory education through a challenging curriculum in the arts and sciences; an integrated From the outset, King’s Academy embraced a commitment co-curricular program of athletics, to educational accessibility, need-based financial aid, and activities and community service; diversity. Over 40 countries are represented at King’s, and and a nurturing residential approximately 74% of students reside on campus. More than environment. Our students 45% of the student body receives financial aid at King’s, and the will learn to be independent, School offers enrichment programs to reach underprivileged creative and responsible thinkers youth in Jordan (see Signature Programs). -

The E Book 2021–2022 the E Book

THE E BOOK 2021–2022 THE E BOOK This book is a guide that sets the standard for what is expected of you as an Exonian. You will find in these pages information about Academy life, rules and policies. Please take the time to read this handbook carefully. You will find yourself referring to it when you have questions about issues ranging from the out-of-town procedure to the community conduct system to laundry services. The rules and policies of Phillips Exeter Academy are set by the Trustees, faculty and administration, and may be revised during the school year. If changes occur during the school year, the Academy will notify students and their families. All students are expected to follow the most recent rules and policies. Procedures outlined in this book apply under normal circumstances. On occasion, however, a situation may require an immediate, nonstandard response. In such circumstances, the Academy reserves the right to take actions deemed to be in the best interest of the Academy, its employees and its students. This document as written does not limit the authority of the Academy to alter its rules and procedures to accommodate any unusual or changed circumstances. If you have any questions about the contents of this book or anything else about life at Phillips Exeter Academy, please feel free to ask. Your teachers, your dorm proctors, Student Listeners, and members of the Dean of Students Office all are here to help you. Phillips Exeter Academy 20 Main Street, Exeter, New Hampshire Tel 603-772-4311 • www.exeter.edu 2021 by the Trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy HISTORY OF THE ACADEMY Phillips Exeter Academy was founded in 1781 A gift from industrialist and philanthropist by Dr. -

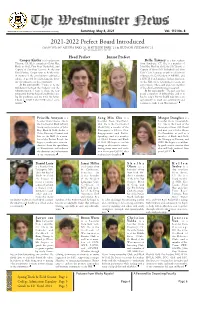

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

School Brochure

Bring Global Diversity to Your Campus with ASSIST 52 COUNTRIES · 5,210 ALUMNI · ONE FAMILY OUR MISSION ASSIST creates life-changing opportunities for outstanding international scholars to learn from and contribute to the finest American independent secondary schools. Our Vision WE BELIEVE that connecting future American leaders with future “Honestly, she made me think leaders of other nations makes a substantial contribution toward about the majority of our texts in brand new ways, and increasing understanding and respect. International outreach I constantly found myself begins with individual relationships—relationships born taking notes on what she through a year of academic and cultural immersion designed would say, knowing that I to affect peers, teachers, friends, family members and business would use these notes in my teaching of the course associates for a lifetime. next year.” WE BELIEVE that now, more than ever, nurturing humane leaders “Every time I teach this course, there is at least one student through cross-cultural interchange affords a unique opportunity in my class who keeps me to influence the course of future world events in a positive honest. This year, it’s Carlota.” direction. “Truly, Carlota ranks among the very best of all of the students I have had the opportunity to work with during my nearly 20 years at Hotchkiss.” ASSIST is a nonprofit organization that works closely with American independent secondary Faculty members schools to achieve their global education and diversity objectives. We identify, match The Hotchkiss School and support academically talented, multilingual international students with our member Connecticut schools. During a one-year school stay, an ASSIST scholar-leader serves as a cultural ambassador actively participating in classes and extracurricular activities. -

Avon, Connecticut

AVON OLD FARMS SCHOOL AVON, CONNECTICUT HEAD OF SCHOOL POSITION START DATE: JULY 1, 2019 www.avonoldfarms.com Mission Avon Old Farms School strives to be the best college preparatory school for boys by cultivating young men of integrity who honor wisdom, justice, inclusion, service, and the pursuit of truth. OVERVIEW Avon Old Farms School, an independent boarding school for boys in grades 9-12, seeks a Headmaster who will embrace the school’s mission of educating young men and exemplify the school’s core values. In a spirited community of learners, Avon offers students unwavering support and fraternal bonds that last a lifetime. The school strives to be the top college prep boys boarding school in the country, inspiring boys and helping them along the road to self-discovery, independence, and manhood. The school knows and understands boys and has created an educational and social environment where boys can thrive, learn, and explore in an atmosphere of brotherhood. The school’s founder, Theodate Pope Riddle, one of America’s first licensed female architects, designed the school and its early curriculum and approach to learning. Her personal fortitude and educational vision in 1927 created the groundwork for an institution that continues to challenge boys in the pursuit of knowledge and self-improvement. In January, Ken LaRocque announced his retirement, effective at the end of the 2019 school year, representing 38 years at the school, 21 of them as Headmaster. The Board of Directors, together with a Search Committee, is seeking a new Headmaster who will be responsible for leading Avon as it continues its mission of leading boys on the journey to becoming men. -

Mindingbusiness the 4 ALUMNI-RUN COMPANIES

BULLETIN MindingBusiness the 4 ALUMNI-RUN COMPANIES WINTER 2018 In this ISSUE WINTER 2018 40 38 Minding the Business How Charlie Albert ’69, JJ Rademaekers ’89, AK Kennedy L’Heureux ’90, and James McKinnon ’87 achieved entrepreneurial success—and DEPARTMENTS became their own bosses 3 On Main Hall By Neil Vigdor ’95 8 Alumni Spotlight 16 Around the Pond 32 Sports 38 Larry Stone Tribute 66 Alumni Notes 58 106 Milestones How to Work Smarter, Not Harder The Moorhead Academic Center and Jon Willson ’82 in action By Julie Reiff 58 40 m Taft varsity football celebrates their 41–23 victory over Hotchkiss School on November 11. ROBERT FALCETTI Taft Bulletin / WINTER 2018 1 On Main Hall A WORD FROM HEADMASTER WILLY MACMULLEN ’78 WINTER 2018 Volume 88, Number 2 EDITOR Linda Hedman Beyus DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kaitlin Thomas Orfitelli THE RIGORS AND REWARDS OF ACCREDITATION ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Debra Meyers There are lots of ways schools improve. Boards plan strategically, heads and “We have hard ON THE COVER administrative teams examine and change practices, and faculty experiment PHOTOGRAPHY work to do, but it’s A model of a Chuggington® train—inspired by the Robert Falcetti and innovate. But for schools like Taft, there’s another critical way: the New children’s animated show of the same name—greets England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) Accreditation Process. It’s a the glorious work readers on this issue’s cover! Read the feature on ALUMNI NOTES EDITOR pages 40–57 about four alumni who create and make really rigorous methodology that ensures accredited schools regularly reflect, Hillary Dooley on challenges different products, including toy/games designer plan, and innovate; and it’s this process Taft just finished. -

LOG17 Issue 1 Merged 9/20.Indd

Loomis Chaffee Log SEPTEMBER 26, 2016 Issue 101, No. 1 thelclog.org M I N D OVER MATTER Graphic by Anh Nguyen ’17 How should we navigate this year’s vague all-school theme, “MIND OVER MATTER?” very year, the all-school theme encourages students to stretch the “Loomis bubble” and think critically about day to day oc- currences — from the environmental implications of fl ipping a light switch to the media we consume on Twitter. This year, the schoolE theme was fi rst alluded to in our puzzling all-school read, The Little Prince. During the fi rst weeks of school, the administration has presented the theme in a narrow sense, raising eyebrows. Is it really that effective to have the junior class do yoga in the quad? Are the talks on de-stressing stressful? Is mindfulness limited to stress relief? Given the emphasis on alleviating the stress we cannot eliminate, it is too easy to dismiss the mantra rather than seriously investing in it. (continued on page 8) NEWS: SEPTEMBER WRITING CENTER TO OPEN PELICAN VACATION IN EARLY OCTOBER EDITORS’ OP-ED: Akash Chadalavada ’18 | News Editor SENIORITY SPIRIT riting, the bane of many a Loomis student, is a fi ery crucible PICKS that can either make or break a grade. For that exact reason, a newW studio designed to help students with all forms of writing is in SPORTS: the works. The new Writing Studio, which will share a space with what is currently the Kravis Center for Excellence in Teaching, has been THE NFL PREVIEW specifi cally designed to help students with writing assignments for any department. -

2021 Semifinalists for the U.S. Presidential Scholars Program

Semifinalists for the U.S. Presidential Scholars Program April 2021 * Semifinalist for U.S. Presidential Scholar in Arts. ** Semifinalist for U.S Presidential Scholar in Career and Technical Education. *** Semifinalist for U.S. Presidential Scholar and U.S. Presidential Scholar in the Arts. **** Semifinalist for U.S. Presidential Scholar and U.S. Presidential Scholar in Career and Technical Education. Alabama AL - Gabriel Au, Auburn - Auburn High School AL - Gregory T. Li, Spanish Fort - Alabama School of Mathematics and Science AL - Joshua Hugh Lin, Madison - Bob Jones High School AL - Josie McGuire, Leeds - Leeds High School AL - Nikhita Sainaga Mudium, Madison - James Clemens High School AL - Soojin Park, Auburn - Auburn High School **AL - Brannan Cade Tisdale, Saraland - Saraland High School AL - Cary Xiao, Tuscaloosa - Alabama School of Math & Science AL - Ariel Zhou, Vestavia Hills - Vestavia Hills High School Alaska AK - Ezra Adasiak, Fairbanks - Austin E. Lathrop High School AK - Margaret Louise Ludwig, Wasilla - Mat-Su Career and Technical High School AK - Evelyn Alexandra Nutt, Ketchikan - Ketchikan High School AK - Alex Prayner, Wasilla - Mat-Su Career and Technical High School AK - Parker Emma Rabinowitz, Girdwood - Hawaii Preparatory Academy AK - Sawyer Zane Sands, Dillingham - Dillingham High School Americans Abroad AA - Haddy Elie Alchaer, Maumelle - International College AA - Sebastian L. Castro, Tamuning - Harvest Christian Academy AA - Victoria M. Geehreng, Brussels - Brussels American School AA - Andrew Woo-jong Lee, Hong Kong - Choate Rosemary Hall AA - Emily Patrick, APO - Ramstein American High School AA - Victoria Nicole Maniego Santos, Saipan - Mount Carmel High School Arizona AZ - Gabriel Zhu Adams, Mesa - BASIS Mesa AZ - Jonny Auh, Scottsdale - Desert Mountain High School *AZ - Yuqi Bian, Cave Creek - Interlochen Arts Academy AZ - Manvi Harde, Chandler - Hamilton High School AZ - Viraj Mehta, Scottsdale - BASIS Scottsdale Charter AZ - Alexandra R. -

Ethel Walker School

Ethel Walker School The Ethel Walker School Location Information A private, college preparatory, boarding and day school for girls in grades 6 through Type 12 plus postgraduate located in Simsbury, Connecticut. Nullas Horas Nisi Aureas Motto "Nothing But Golden Hours" Established 1911 by Ethel Walker Head of Dr. Meera Viswanathan School Grades 6-12 plus postgraduate Gender Girls Number of 250 students Average class 12 size Student to 1:7 teacher ratio Campus size 175 acres School Purple and Yellow color(s) Website www.ethelwalker.org The Ethel Walker School, also commonly referred to as “Walker’s”, is a private, college preparatory, boarding and day school for girls in grades 6 through 12 plus postgraduate located in Simsbury, Connecticut. Main academic building, Beaver Brook, at The Ethel Walker School Chapel at The Ethel Walker School Notable alumnae Ethel du Pont, heiress and socialite[1] Notes 1. ^ "SON OF PRESIDENT TO WED MISS DUPONT Troth of Ethel, Wilmington Heiress, to Franklin Jr. Is Made Known. WEDDING SET FOR JUNE 2. Fiance, Student at Harvard, to Remain There Until After His Graduation. THE PRESIDENT'S SON AND HIS FIANCEE ROOSEVELT JR. WINS MISS ETHEL DU PONT". The New York Times. November 15, 1936. Retrieved 14 August 2016. External links Ethel Walker School Website The Association of Boarding Schools profile Brunswick School (Greenwich) Fairfield College Preparatory School (Fairfield) Private boys' schools Notre Dame High School (West Haven) Xavier High School (Middletown) Academy of the Holy Family (Baltic) Academy -

The Loomis Chaffee School 2010 Fall Athletic Awards Ceremony Sunday, December 5, 2010

The Loomis Chaffee School 2010 Fall Athletic Awards Ceremony Sunday, December 5, 2010 Boys Cross Country Girls Cross Country Football Field Hockey Boys Soccer Girls Soccer Volleyball Water Polo Loomis Chaffee Athletic Awards Tea Fall 2010 Season Sunday, December 5 2010 Program Introduction: Bob Howe ’80, Athletic Director Boys Water Polo: Bob Howe Girls Cross Country: Bobbi D. Moran Football: Bob Howe Boys Cross Country: Bobbi D. Moran Girls Soccer: Bob Howe Field Hockey: Bobbi D. Moran Boys Soccer: Bob Howe Girls Volleyball: Bob Howe Closing Remarks: Bob Howe LOOMIS CHAFFEE BOYS WATER POLO 2010 TEAM HISTORY Water Polo at Loomis Chaffee dates back to the late-70's when Coach Bob Hartman created one of the first high school programs in New England. This co-ed team eventually split into girls and boys varsity programs in the mid -90's with both teams having consistent success in their respective leagues. The Pelican's won the New England Prep School Championship Tournament in 1994 and 1996, finished second in 1999, 2002, and 2003 and third in 2001. 2010 STATISTICS Overall Record: 6-10 Goals – A. Wright 40, R. Carroll 28, W. DeLaMater 19 Assists – A. Wright 33, W. DeLaMater 28, S. Broda 12 Steals – A.Wright 55, S. Broda 37, W. DeLaMater 34 2010 SEASON Coming off of a 2009 campaign that ended with at 1-15 record, the Pelicans had reason to be optimistic for a more competitive 2010 season. Key returning players from last year’s team, juniors Addison Wright and Sam Broda along with captain Rob Carroll and a large group of seniors including Will DeLaMater, Dan Kang, Nick Fainlight and Kyle Ruddock formed the nucleus for the varsity. -

Choate @ Deerfield 1-25-2020 Event 1 Girls 200 Yard Medley Relay 1 CHOATE ROSE

Deerfield Academy HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 6:02 PM 1/25/2020 Page 1 Choate@Deerfield 1-25-2020 - 1/25/2020 Results - Choate @ Deerfield 1-25-2020 Event 1 Girls 200 Yard Medley Relay Team Relay Seed Time Finals Time Points 1 CHOATE ROSEMARY HALL A NT 1:50.47 8 1) Cronin, Mealy 2) Tray, Zoe 3) So, Isabelle 4) Scott, Samantha 2 DEERFIELD ACADEMY A NT 1:53.85 4 1) Hamlen, Izzy 2) Mark, Rachel 3) del Real, Darcy 4) Pelletier, Niki 3 CHOATE ROSEMARY HALL B NT 1:58.64 2 1) Gazda, Laryssa 2) McAndrew, Sarah 3) Solano-Florez, Laura 4) Xiao, Tiffany 4 DEERFIELD ACADEMY B NT 2:01.55 1) Hamlen, Sophia 2) Otis, Charlotte 3) Mahony, Caroline 4) Poonsonsornsiri, Aim 5 CHOATE ROSEMARY HALL C NT x2:09.30 1) O'Leary, Kaleigh 2) Moh, Charlotte 3) Furtado, Grace 4) Bohan, Grace 6 DEERFIELD ACADEMY C NT x2:24.72 1) Howe, Cam 2) He, Jing 3) Sall, Nafi 4) Lawrence, Katie --- DEERFIELD ACADEMY D NT X2:24.99 1) Cui, Angela 2) Konar, Olivia 3) Tydings, Maggie 4) Klem, Lourdes Event 2 Boys 200 Yard Medley Relay Team Relay Seed Time Finals Time Points 1 CHOATE ROSEMARY HALL A NT 1:40.75 8 1) Xu, Max 2) Sun, Jack 3) Kwan, Adrian 4) Scott, Parker 2 DEERFIELD ACADEMY A NT 1:42.64 4 1) Smith, Thatcher 2) Cai, Mark 3) Zhao, Mason 4) O'Loughlin, John 3 DEERFIELD ACADEMY B NT 1:48.76 2 1) Huang, Jerry 2) Salmassi, Cyrus 3) Kim, Sean 4) McCarthy, Teddy 4 CHOATE ROSEMARY HALL B NT 1:51.99 1) Chang, Kevin 2) Bershtein, Hunter 3) Alataris, Priam 4) Son, Derek 5 DEERFIELD ACADEMY C NT x1:57.99 1) McGuinness, Hudson 2) Osbourne, Peter 3) Cullinane, Declan 4) Barrett, Erol -

The Official Boarding Prep School Directory Schools a to Z

2020-2021 DIRECTORY THE OFFICIAL BOARDING PREP SCHOOL DIRECTORY SCHOOLS A TO Z Albert College ON .................................................23 Fay School MA ......................................................... 12 Appleby College ON ..............................................23 Forest Ridge School WA ......................................... 21 Archbishop Riordan High School CA ..................... 4 Fork Union Military Academy VA ..........................20 Ashbury College ON ..............................................23 Fountain Valley School of Colorado CO ................ 6 Asheville School NC ................................................ 16 Foxcroft School VA ..................................................20 Asia Pacific International School HI ......................... 9 Garrison Forest School MD ................................... 10 The Athenian School CA .......................................... 4 George School PA ................................................... 17 Avon Old Farms School CT ...................................... 6 Georgetown Preparatory School MD ................... 10 Balmoral Hall School MB .......................................22 The Governor’s Academy MA ................................ 12 Bard Academy at Simon's Rock MA ...................... 11 Groton School MA ................................................... 12 Baylor School TN ..................................................... 18 The Gunnery CT ........................................................ 7 Bement School MA.................................................