Amendments: 109Th Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Committees 2021

Key Committees 2021 Senate Committee on Appropriations Visit: appropriations.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patrick J. Leahy, VT, Chairman Richard C. Shelby, AL, Ranking Member* Patty Murray, WA* Mitch McConnell, KY Dianne Feinstein, CA Susan M. Collins, ME Richard J. Durbin, IL* Lisa Murkowski, AK Jack Reed, RI* Lindsey Graham, SC* Jon Tester, MT Roy Blunt, MO* Jeanne Shaheen, NH* Jerry Moran, KS* Jeff Merkley, OR* John Hoeven, ND Christopher Coons, DE John Boozman, AR Brian Schatz, HI* Shelley Moore Capito, WV* Tammy Baldwin, WI* John Kennedy, LA* Christopher Murphy, CT* Cindy Hyde-Smith, MS* Joe Manchin, WV* Mike Braun, IN Chris Van Hollen, MD Bill Hagerty, TN Martin Heinrich, NM Marco Rubio, FL* * Indicates member of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, which funds IMLS - Final committee membership rosters may still be being set “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Visit: help.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patty Murray, WA, Chairman Richard Burr, NC, Ranking Member Bernie Sanders, VT Rand Paul, KY Robert P. Casey, Jr PA Susan Collins, ME Tammy Baldwin, WI Bill Cassidy, M.D. LA Christopher Murphy, CT Lisa Murkowski, AK Tim Kaine, VA Mike Braun, IN Margaret Wood Hassan, NH Roger Marshall, KS Tina Smith, MN Tim Scott, SC Jacky Rosen, NV Mitt Romney, UT Ben Ray Lujan, NM Tommy Tuberville, AL John Hickenlooper, CO Jerry Moran, KS “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Finance Visit: finance.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Ron Wyden, OR, Chairman Mike Crapo, ID, Ranking Member Debbie Stabenow, MI Chuck Grassley, IA Maria Cantwell, WA John Cornyn, TX Robert Menendez, NJ John Thune, SD Thomas R. -

Senate Republican Conference John Thune

HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE JOHN THUNE 115th Congress Revised January 2017 HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE Table of Contents Preface ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 1 Rules of the Senate Republican Conference ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....2 A Service as Chairman or Ranking Minority Member ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 B Standing Committee Chair/Ranking Member Term Limits ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 C Limitations on Number of Chairmanships/ Ranking Memberships ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 D Indictment or Conviction of Committee Chair/Ranking Member ....... ....... ....... .......5 ....... E Seniority ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... 5....... ....... ....... ...... F Bumping Rights ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 G Limitation on Committee Service ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ...5 H Assignments of Newly Elected Senators ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 Supplement to the Republican Conference Rules ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 6 Waiver of seniority rights ..... -

Ranking Member John Barrasso

Senate Committee Musical Chairs August 15, 2018 Key Retiring Committee Seniority over Sitting Chair/Ranking Member Viewed as Seat Republicans Will Most Likely Retain Viewed as Potentially At Risk Republican Seat Viewed as Republican Seat at Risk Viewed as Seat Democrats Will Most Likely Retain Viewed as Potentially At Risk Democratic Seat Viewed as Democratic Seat at Risk Notes • The Senate Republican leader is not term-limited; Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY) will likely remain majority leader. The only member of Senate GOP leadership who is currently term-limited is Republican Whip John Cornyn (R-TX). • Republicans have term limits of six years as chairman and six years as ranking member. Republican members can only use seniority to bump sitting chairs/ranking members when the control of the Senate switches parties. • Committee leadership for the Senate Aging; Agriculture; Appropriations; Banking; Environment and Public Works (EPW); Health Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP); Indian Affairs; Intelligence; Rules; and Veterans Affairs Committees are unlikely to change. Notes • Current Armed Services Committee (SASC) Chairman John McCain (R-AZ) continues to receive treatment for brain cancer in Arizona. Senator James Inhofe (R-OK) has served as acting chairman and is likely to continue to do so in Senator McCain’s absence. If Republicans lose control of the Senate, Senator McCain would lose his top spot on the committee because he already has six years as ranking member. • In the unlikely scenario that Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA) does not take over the Finance Committee, Senator Mike Crapo (R-ID), who currently serves as Chairman of the Banking Committee, could take over the Finance Committee. -

Senator John Cornyn

Please Join JAMES DICKEY Chairman of the Republican Party of Texas With Honored Guest Senator John Cornyn For a conversation and luncheon benefitting the Republican Party of Texas Friday, September 28th, 2018 11:30 AM – 1:00 PM La Griglia 2002 W. Gray St. Houston, TX 77019 Kindly RSVP to Marissa Vredeveld at [email protected] or 616.481.1186 Senator John Cornyn is appearing at this event as a special guest. Any funds solicited in connection with this event are by the Republican Party of Texas and not by Senator Cornyn. Paid for by the Republican Party of Texas and not authorized by any candidate or candidate’s committee. www.texasgop.org REPUBLICAN PARTY OF TEXAS RECEPTION FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 11:30 AM – 1:00 PM 2002 W. GRAY ST. HOUSTON, TX 77019 ____ I/we will attend: ______________________________________________________________________ Host: $10,000 (6 tickets and recognition at the event) Sponsor: $5,000 (4 tickets and recognition at the event) Attendee: $1,000 (1 ticket) Young Professional (40 and under): $500 (1 ticket) ____ I am unable to attend the reception but have enclosed a contribution in the amount of: $_________. ________________________________________________________________________________________ Full Name ________________________________________________________________________________________ Address City State Zip Code ________________________________________________________________________________________ Home Phone Work Phone E-Mail ________________________________________________________________________________________ Employer Occupation Please mail and make checks payable to: Republican Party of Texas P.O. Box 2206 Austin, TX 78768 Credit Card Contributions: This contribution to the Republican Party of Texas is drawn on my personal credit card, represents my personal funds, and is not drawn on an account maintained by an incorporated entity. -

Senator Cory Gardner, Colorado - NRSC Chairman Mrs

NRSC FALL DONOR RETREAT FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2018 – SUNDAY, DECEMBER 2, 2018 SEA ISLAND, GEORGIA ATTENDING U.S. SENATORS AND SPOUSES: Senator Cory Gardner, Colorado - NRSC Chairman Mrs. Jaime Gardner Senator Shelley Moore Capito, West Virginia Mr. Charlie Capito Senator David Perdue, Georgia Mrs. Bonnie Perdue Senator Roger F. Wicker, Mississippi Mrs. Gayle Wicker Senator Todd Young, Indiana – Incoming NRSC Chairman ATTENDEES As of 11/27/2018 Jon Adams, NRSC Michael Adams, MLM Group Tom Adams, Targeted Victory Tessa Adams, NRSC Rachel Africk Mark Alagna, UPS Joshua Alderman, Accenture Katie Allen, AHIP Bryan Anderson, Southern Company Brandon Audap Amy Barrera, Office of Senator Cory Gardner Dan Barron, Alliance Resource Partners Kate Beaulieu, NBWA Megan Becker, NRSC Katie Behnke, NRSC Ryan Berger, NRSC Jonathan Bergner, NAMIC Brianna Bergner, Equinix Kristine Blackwood, Arnold & Porter, LLC Denise Bode, Michael Best Strategies John Bode, Corn Refiners Association Doyce Boesch, Boesch and Company Jacqueline Boesch Dave Boyer, BGR Group Claire Brandewie, McKesson Drew Brandewie, U.S. Senator John Cornyn Mimi Braniff, Delta Air Lines Andy Braniff William Burton, Sagat Burton LLP Michele Burton Cort Bush, Comcast NBCUniversal Frank Cavaliere, Microsoft Corporation Rob Chamberlin, Signal Group Cindy Chetti, National Multifamily Housing Council Jolyn Cikanek, Genworth Financial David Cobb, HDR Aaron Cohen, Capitol Counsel James Comerford, 1908 CAPITAL Camilla Comerford John Connell, Office of Senator Todd Young Tim Constantine, Constantine -

Biden 48, Trump 44 in Texas, Quinnipiac University Poll Finds; Democrats Say 2-1 O’Rourke Should Challenge Cornyn

Peter A. Brown, Assistant Director (203) 535-6203 Rubenstein Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR RELEASE: JUNE 5, 2019 BIDEN 48, TRUMP 44 IN TEXAS, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY POLL FINDS; DEMOCRATS SAY 2-1 O’ROURKE SHOULD CHALLENGE CORNYN President Donald Trump is locked in too-close-to-call races with any one of seven top Democratic challengers in the 2020 presidential race in Texas, where former Vice President Joseph Biden has 48 percent to President Trump with 44 percent, according to a Quinnipiac University poll released today. Other matchups by the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University Poll show: President Trump at 46 percent to Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren at 45 percent; Trump at 47 percent to Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders at 44 percent; Trump at 48 percent to former U.S. Rep. Beto O’Rourke with 45 percent; Trump with 46 percent to South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s 44 percent; Trump at 47 percent to California Sen. Kamala Harris at 43 percent; Trump with 46 percent and former San Antonio Mayor Julian Castro at 43 percent. In the Trump-Biden matchup, women back Biden 54 – 39 percent as men back Trump 50 – 42 percent. White voters back Trump 60 – 33 percent. Biden leads 86 – 7 percent among black voters and 59 – 33 percent among Hispanic voters. Republicans back Trump 90 – 8 percent. Biden leads 94 – 4 percent among Democrats and 55 – 33 percent among independent voters. “The numbers are good for Vice President Joseph Biden who dominates the field in a Democratic primary and has the best showing in a head-to-head match-up against President Donald Trump,” said Peter A. -

List of Government Officials (May 2020)

Updated 12/07/2020 GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS PRESIDENT President Donald John Trump VICE PRESIDENT Vice President Michael Richard Pence HEADS OF EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTS Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar II Attorney General William Barr Secretary of Interior David Bernhardt Secretary of Energy Danny Ray Brouillette Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Benjamin Carson Sr. Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao Secretary of Education Elisabeth DeVos (Acting) Secretary of Defense Christopher D. Miller Secretary of Treasury Steven Mnuchin Secretary of Agriculture George “Sonny” Perdue III Secretary of State Michael Pompeo Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross Jr. Secretary of Labor Eugene Scalia Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert Wilkie Jr. (Acting) Secretary of Homeland Security Chad Wolf MEMBERS OF CONGRESS Ralph Abraham Jr. Alma Adams Robert Aderholt Peter Aguilar Andrew Lamar Alexander Jr. Richard “Rick” Allen Colin Allred Justin Amash Mark Amodei Kelly Armstrong Jodey Arrington Cynthia “Cindy” Axne Brian Babin Donald Bacon James “Jim” Baird William Troy Balderson Tammy Baldwin James “Jim” Edward Banks Garland Hale “Andy” Barr Nanette Barragán John Barrasso III Karen Bass Joyce Beatty Michael Bennet Amerish Babulal “Ami” Bera John Warren “Jack” Bergman Donald Sternoff Beyer Jr. Andrew Steven “Andy” Biggs Gus M. Bilirakis James Daniel Bishop Robert Bishop Sanford Bishop Jr. Marsha Blackburn Earl Blumenauer Richard Blumenthal Roy Blunt Lisa Blunt Rochester Suzanne Bonamici Cory Booker John Boozman Michael Bost Brendan Boyle Kevin Brady Michael K. Braun Anthony Brindisi Morris Jackson “Mo” Brooks Jr. Susan Brooks Anthony G. Brown Sherrod Brown Julia Brownley Vernon G. Buchanan Kenneth Buck Larry Bucshon Theodore “Ted” Budd Timothy Burchett Michael C. -

Senate Judiciary Liability Protection Letter

July 30, 2020 The Honorable Lindsey Graham The Honorable Dianne Feinstein Chairman, Judiciary Committee Ranking Member, Judiciary Committee United States Senate United States Senate 290 Russell Senate Office Building 331 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Dear Chairman Graham and Ranking Member Feinstein: On behalf of our 163,000 dentist members, the American Dental Association (ADA) would like to thank the Senate Judiciary Committee for reviewing and hopefully advancing the Safeguarding America’s Frontline Employees to Offer Work Opportunities Required to Kickstart the Economy, or SAFE TO WORK Act (S. 4317). The health care liability protections in this bill provide small business dental owners with safeguards against coronavirus-based claims that could derail the progress made in reopening their practices. Additionally, the bill highlights Congress’ strong commitment to small health care businesses by granting temporary labor and employment law protection and clarifying already existing product liability protections. After closing completely or limiting their practices to emergency-only dental care at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, dentists across the country have reopened their practices. While safeguarding their patients, their staff, and themselves from the spread of COVID-19, dental practices must also safeguard their businesses from bad-faith actors pursuing frivolous financial gain for coronavirus-related injuries. The exclusive federal clause of action in the SAFE TO WORK Act provides dentists with comfort and protection from unsubstantiated medical liability claims. As you are aware, this clause of action is the exclusive remedy for personal injury caused by the treatment, diagnosis, or care of coronavirus, or care directly affected by the coronavirus. -

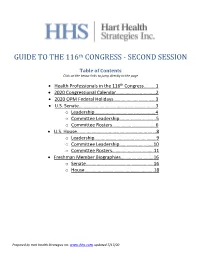

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

Falsities on the Senate Floor John Cornyn United States Senator

University of Richmond Law Review Volume 39 Issue 3 Allen Chair Symposium 2004 Federal Judicial Article 13 Selection 3-2005 Falsities on the Senate Floor John Cornyn United States Senator Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview Part of the American Politics Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation John Cornyn, Falsities on the Senate Floor, 39 U. Rich. L. Rev. 963 (2005). Available at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol39/iss3/13 This Letter is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Richmond Law Review by an authorized editor of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALSITIES ON THE SENATE FLOOR * The Honorable John Cornyn ** Throughout last night's historic round-the-clock session of the United States Senate, a partisan minority of senators defended their filibusters against the President's judicial nominees by mak- ing two basic arguments. Both were false. First, they claim that the Senate's record of "168-4"-168 judges confirmed, 4 filibustered (so far)-somehow proves that the cur- rent filibuster crisis is mere politics as usual.1 But, as I explained in an op-ed yesterday, this is not politics as usual; it is politics at its worst.2 * An earlier version of this Article was originally published on the National Review Online website on November 13, 2003. John Cornyn, Falsities on the Senate Floor, NAT'L REV. ONLINE, Nov. -

Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress

Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION AND FORESTRY BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Pat Roberts, Kansas Debbie Stabenow, Michigan Mike Crapo, Idaho Sherrod Brown, Ohio Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont Richard Shelby, Alabama Jack Reed, Rhode Island Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Sherrod Brown, Ohio Bob Corker, Tennessee Bob Menendez, New Jersey John Boozman, Arkansas Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota Pat Toomey, Pennsylvania Jon Tester, Montana John Hoeven, North Dakota Michael Bennet, Colorado Dean Heller, Nevada Mark Warner, Virginia Joni Ernst, Iowa Kirsten Gillibrand, New York Tim Scott, South Carolina Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts Chuck Grassley, Iowa Joe Donnelly, Indiana Ben Sasse, Nebraska Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota John Thune, South Dakota Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota Tom Cotton, Arkansas Joe Donnelly, Indiana Steve Daines, Montana Bob Casey, Pennsylvania Mike Rounds, South Dakota Brian Schatz, Hawaii David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland Luther Strange, Alabama Thom Tillis, North Carolina Catherine Cortez Masto, Nevada APPROPRIATIONS John Kennedy, Louisiana REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC BUDGET Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Mitch McConnell, Patty Murray, Kentucky Washington Mike Enzi, Wyoming Bernie Sanders, Vermont Richard Shelby, Dianne Feinstein, Alabama California Chuck Grassley, Iowa Patty Murray, -

Developments That Matter

Developments That Matter Chamber Rolls Out Senate Endorsements It’s been a busy stretch for the U.S. Chamber’s political program as we’ve rolled out nine United States Senate campaign endorsements in the last three weeks. As shared in our previous update, the pandemic has disrupted the normal cadence of a typical campaign calendar. As a result, the manner in which we are releasing endorsements, and the timing itself, are slightly different than in cycles past. We’ve been very pleased with the positive news coverage and local earned media garnered for the Chamber-backed candidates we are supporting. Here are a few notable endorsements. More can be found on our website. • On June 22, the Chamber endorsed Bill Hagerty in the open U.S. Senate seat in Tennessee. A former Ambassador to Japan and business leader, Hagerty’s endorsement by the Chamber was covered in the Tennessean for this multi-candidate primary race. • The Chamber announced the endorsement of U.S. Representative, Dr. Roger Marshall (KS-Sen) on June 23. The Kansas City Star reported on the Marshall endorsement, and noted his 90% cumulative score in the latest U.S. Chamber’s “How They Voted” scorecard. Marshall is running in a multi-candidate primary contest in an open seat. Marshall also has been endorsed by the Wichita Regional Chamber of Commerce. • On June 25, the Chamber announced an endorsement for Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) who is running for his first re-election after defeating an incumbent in 2014. The North State Journal covered the endorsement and noted Sen.