International Museum Day 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster-Cultural-Heritage-Strategy

Page 12 LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY REPORT FOR LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL Page 13 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................3 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................7 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................10 3 RECENT VISIONING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 24 4 HOW LANCASTER COMPARES AS A HERITAGE CITY...............28 5 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S BUILT FABRIC .....................................32 6 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S CULTURAL HERITAGE ATTRACTIONS39 7 THE MANAGEMENT OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 48 8 THE MARKETING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE.....51 9 CONCLUSIONS: SWOT ANALYSIS................................................59 10 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES FOR LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE .......................................................................................65 11 INVESTMENT OPTIONS..................................................................67 12 OUR APPROACH TO ASSESSING ECONOMIC IMPACT ..............82 13 TEN YEAR INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK .......................................88 14 ACTION PLAN ...............................................................................107 APPENDICES .......................................................................................108 2 Page 14 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lancaster is widely recognised -

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir From 1899 to 2013 this history is based on the writings of Roland Brooke and the first history contained in the original website (no longer operational). From 2013 it is the work of Dr Hugh Cutler sometime Chairman and subsequently Communications Officer and editor of the website. The Years 1899-1950 The only indication of the year of foundation is that 1899 is mentioned in an article in the Lancaster Guardian dated 13th November 1926 regarding the Golden Wedding Anniversary of Mr. & Mrs. R.T. Grosse. In this article it states that he was 'for many years the Conductor of the Lancaster Male Voice Choir which was formed at the end of 1899'. The Guardian in February 1904 reported that 'the Lancaster Male Voice Choir, a new organisation in the Borough, are to be congratulated on the success of their first public concert'. The content of the concert was extensive with many guest artistes including a well-known soprano at that time, Madame Sadler-Fogg. In the audience were many honoured guests, including Lord Ashton, Colonel Foster, and Sir Frederick Bridge. In his speech, the latter urged the Choir to 'persevere and stick together'. Records state that the Choir were 'at their zenith' in 1906! This first public concert became an annual event, at varying venues, and their Sixth Annual Concert was held in the Ashton Hall in what was then known as 'The New Town Hall' in Lancaster. This was the first-ever concert held in 'The New Town Hall', and what would R.T. -

Lancaster City Museum's Access Statement

Access Statement for Lancaster City Museum This access statement does not contain personal opinions as to our suitability for those with access needs, but aims to accurately describe the facilities and services that we offer all our visitors. Introduction Lancaster City Museum. The City Museum is prominently positioned in Market Square. It is within walking distance of both the train and bus stations. Lancaster City Museum is a VAQAS Quality Assured Visitor Attraction. It comprises both the City Museum collection, and the King’s Own Royal Regiment Museum. The ground floor is completely accessible, and can be reached via the main steps or a ramp which is accessed by the entrance to Lancaster Library. The first floor is accessed by the main staircase. There is a stair lift which is regrettably not accessible to wheelchairs which exceed the weight limit. In the event of an evacuation, wheelchair users will be evacuated using the museum evac chair, by a trained member of staff. For this reason, only one wheelchair can be permitted on the first floor at any one time. A Hearing Loop is available. Pre-Arrival Lancaster Railway station is less than 1 mile away and has a taxi rank situated outside. Both major local taxi services can provide accessible vehicles (see p.5 for details). Lancaster Bus station is less than 1 mile away and the route from the station to the museum is up a mild uphill slope. Pedestrian access to the museum is very good. Car Parking and Arrival There is no parking available on site, due to the city centre location of the museum. -

The First World War

OTHER PLACES OF INTEREST Lancaster & Event Highlights NOW AND THEN – LINKING PAST WITH THE PRESENT… Westfield War Memorial Village The First The son of the local architect, Thomas Mawson, was killed in April Morecambe District 1915 with the King’s Own. The Storey family who provided the land of World War Sat Jun 21 – Sat Oct 18 Mon Aug 4 Wed Sep 3 Sat Nov 8 the Westfield Estate and with much local fundraising the village was First World War Centenary War! 1914 – Lancaster and the Kings Own 1pm - 2pm Origins of the Great War All day ‘Britons at War 1914 – 1918’ 7:30pm - 10pm Lancaster and established in the 1920s and continued to be expanded providing go to War, Exhibition Lunchtime Talk by Paul G.Smith District Male Voice Choir Why remember? Where: Lancaster City Museum, Market Where: Lancaster City Museum, Where: Barton Road Community Centre, Where: The Chapel, University accommodation for soldiers and their families. The village has it’s Square, Lancaster Market Square, Lancaster Barton Road, Bowerham, Lancaster. of Cumbria, Lancaster own memorial, designed by Jennifer Delahunt, the art mistress at Tel: 01524 64637 T: 01524 64637 Tel: 01524 751504 Tel: 01524 582396 EVENTS, ACTIVITIES AND TRAIL GUIDE the Storey Institute, which shows one soldier providing a wounded In August 2014 the world will mark the one hundredth Sat Jun 28 Mon Aug 4 Sat Sep 6 Sun Nov 9 soldier with a drink, not the typical heroic memorial one usually anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. All day Meet the First World War Soldier 7pm - 9pm “Your Remembrances” Talk All day Centenary of the Church Parade of 11am Remembrance Sunday But why should we remember? Character at the City Museum Where: Meeting Room, King’s Own Royal the ‘Lancaster Pals’ of the 5th Battalion, Where: Garden of Remembrance, finds. -

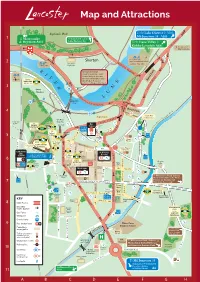

Map and Attractions

Map and Attractions 1 & Heysham to Lancaster City Park & Ride to Crook O’Lune, 2 Skerton t River Lune Millennium Park and Lune Aqueduct Bulk Stree N.B. Greyhound Bridge closed for works Jan - Sept. Skerton Bridge to become two-way. Other trac routes also aected. Please see Retail Park www.lancashire.gov.uk for details 3 Quay Meadow re Ay en re e Park G kat S 4 Retail Park Superstore Vicarage Field Buses & Taxis . only D R Escape H T Room R NO Long 5 Stay Buses & Taxis only Cinema LANCASTER VISITOR Long 6 INFORMATION CENTRE Stay e Gregson Th rket Street Centre Storey Ma Bashful Alley Sir Simons Arcade Long 7 Stay Long Stay Buses & Taxis only Magistrates 8 Court Long Stay 9 /Stop l Cruise Cana BMI Hospital University 10 Hospital of Cumbria visitors 11 AB CDEFG H ATTRACTIONS IN AND Assembly Rooms Lancaster Leisure Park Peter Wade Guided Walks AROUND LANCASTER Built in 1759, the emporium houses Wyresdale Road, Lancaster, LA1 3LA A series of interesting themed walks an eclectic mix of stalls. 01524 68444 around the district. Lancaster Castle lancasterleisurepark.com King Street, Lancaster, LA1 1LG 01524 420905 Take a guided tour and step into a 01524 414251 - GB Antiques Centre visitlancaster.org.uk/whats-on/guided- thousand years of history. lancaster.gov.uk/assemblyrooms Open 10:00 – 17:00 walks-with-peter-wade/ Adults £1.50, Children/OAP 75p, Castle Park, Lancaster, LA1 1YJ Tuesday–Saturday 10:00 - 16:30 Under 5s Free Various dates, start time 2pm. 01524 64998 Closed all Bank Holidays Trade Dealers Free Tickets £3 lancastercastle.com - Lancaster Brewery Castle Grounds open 09:30 – 17:00 daily King Street Studios Monday-Thursday 10:00 - 17:00 Lune Aqueduct Open for guided tours 10:00 – 16:00 Exhibition space and gallery showing art Friday- Sunday 10:00 – 18:00 Take a Lancaster Canal Boat Cruise (some restrictions, please check with modern and contemporary values. -

MORECAMBE LANCASTER City Centre

index to routes lancaster city centre stops morecambe town centre stops Destination Services Bus Station Town Centre Destination Services Bus Station Town Centre H Service Route Operator Leaflet lancaster bus station Stand Stops Stand Stops Morecambe Bus Station A Abbeystead 147 7 C, E L Lancaster Farms 18 6 C, E G 3 2 1 L O Ackenthwaite 555, 556 15 – Low Bentham 80 13 – MORECAMBE T R 2, 2A, Heysham - Morecambe - Lancaster - Hala - University STL 131 R E L D E Abraham Heights 71D M Marsh 71D A Morecambe R Q Town Hall R X2, (Serves Kingsway shops during shopping hours) T T Ambleside 555, 556 15 – Marshaw Road 28 20 C, D CENTRAL DRIVE N CE S S ET T Melling 81, 81B 13 – RE . Arkholme 81A 13 – 4 D T H A K S 3, 3A, Morecambe - Lancaster - University STL 130 Milnthorpe 555, 556 15 – O R C LA R ASDA 6A 17 – R C T C U Morecambe 40, 41, 6A 17 C, D L H X3, B Bare 3, 3A, 4 19 C, D N E A O H N R R C 3, 3A, 4 19 C, D I E . N Beaumont Bridge 55,55A,435,555,556 15 – R N D T . A M R 2, 2A 18 C, D C O F D Visitor M E N N Bilsborrow 40, 41 5 B, E J QU S TO R 4, Heysham - Morecambe - Lancaster - Hala Square - University STL 130 10 – Information E T L N E . U T O O R Blackpool 42 5 B, E Centre N P HOR N N O O Night Services Night Bus Stop M E NT O Queen T A RT S A Bolton–le–Sands 55,55A,435,555,556 15 – D WE Arndale S A R 5 Overton - Heysham - Morecambe - Carnforth STL 135 Nether Kellet 49 14 – T D RO H I Victoria U Shopping R E K Borwick 556 15 – IN P M E Centre R E S E 50 16 – A B T. -

Newsletter Issue No

LANCASHIRE LOCAL HISTORY FEDERATION NEWSLETTER ISSUE NO. 19 MAY 2017 LLHF NEWSLETTER EDITOR: MRS. M. EDWARDS Telephone: 0161 256 6585 email: [email protected] *DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: AUGUST 15th, 2017 PLEASE NOTE REMAINING DEADLINES FOR 2017: AUGUST 15th; NOVEMBER 15th Chair: Marianne Howell 01942 492855 07779677730 [email protected] Vice-Chair: Morris Garratt 0161 439 7202 [email protected] Secretary: John Wilson 03330 062270 [email protected] Treasurer: Peter Bamford 01253 796184 [email protected] Membership Secretary: Zoë Lawson 01772 865347 [email protected] Website Manager: Stephen T. Benson 01772 422808 [email protected] **************************************************************************** The Editor cordially invites you to submit your Society information and your own news, notes, reports, articles and photographs. **************************************************************************** VIEW FROM THE CHAIR By the time you read this, Stockport Historical Society will have hosted our ‘At Home’ and I can assure you it was a very successful event. These occasions are always very interesting, because the chosen speakers impart their knowledge of their own areas and cast light on often-forgotten aspects of their history. Next year we are to be hosted by Leyland Historical Society for what I am sure will be an equally varied and informative 'At Home' programme. (See date on following page. Editor) The day included our brief AGM at which we were able to report an increase in the number of member societies from across the County Palatine and even further afield, which is very encouraging. Our small but purposeful committee has already arranged events for next year, and if you feel you would like to contribute as a committee member to our growing organisation, please contact me. -

Bibliography and References 245

Bibliography and References 245 Bibliography and References Abram, Chris (2006), The Lune Valley: Our Heritage (DVD). Alston, Robert (2003), Images of England: Lancaster and the Lune Valley, Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. Ashworth, Susan and Dalziel, Nigel (1999), Britain in Old Photographs: Lancaster & District, Stroud: Budding Books. Baines, Edward (1824), History, Directory and Gazetteer of the County Palatine of Lancaster. Bentley, John and Bentley, Carol (2005), Ingleton History Trail. Bibby, Andrew (2005), Forest of Bowland (Freedom to Roam Guide), London: Francis Lincoln Ltd. Birkett, Bill (1994), Complete Lakeland Fells, London: Collins Willow. Boulton, David (1988), Discovering Upper Dentdale, Dent: Dales Historical Monographs. British Geological Survey (2002), British Regional Geology: The Pennines and Adjacent Areas, Nottingham: British Geological Survey. Bull, Stephen (2007), Triumphant Rider: The Lancaster Roman Cavalry Stone, Lancaster: Lancashire Museums. Camden, William (1610), Britannia. Carr, Joseph (1871-1897), Bygone Bentham, Blackpool: Landy. Champness, John (1993), Lancaster Castle: a Brief History, Preston: Lancashire County Books. Cockcroft, Barry (1975), The Dale that Died, London: Dent. Copeland, B.M. (1981), Whittington: the Story of a Country Estate, Leeds: W.S. Maney & Son Ltd. Cunliffe, Hugh (2004), The Story of Sunderland Point. Dalziel, Nigel and Dalziel, Phillip (2001), Britain in Old Photographs: Kirkby Lonsdale & District, Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd. Denbigh, Paul (1996), Views around Ingleton, Ingleton and District Tradespeople’s Association. Dugdale, Graham (2006), Curious Lancashire Walks, Lancaster: Palatine Books. Elder, Melinda (1992), The Slave Trade and the Economic Development of 18th Century Lancaster, Keele: Keele University Press. Garnett, Emmeline and Ogden, Bert (1997), Illustrated Wray Walk, Lancaster: Pagefast Ltd. Gibson, Leslie Irving (1977), Lancashire Castles and Towers, Skipton: Dalesman Books. -

Map, Attractions & Accommodation

Map, Attractions & Accommodation 111 & Heysham to Lancaster City Park & Ride 10 to Crook O’Lune, 2 Skerton t River Lune Millennium Park and Lune Aqueduct Bulk Stree 9 Retail Park 3 Quay Meadow re Ay en re e Park G kat S 8 4 Retail Park Superstore Vicarage Field Buses & Taxis . only D R 7 Escape H Room RT NO Long 5 Stay Buses & Taxis only Kanteena 6 Cinema LANCASTER VISITOR Long INFORMATION CENTRE Moor 6 Space Stay e Gregson Th rket Street Centre Storey Ma Bashful Alley Sir Simons Arcade 5 Long 7 Stay Long Stay Buses & Taxis 4 only Magistrates Court and 8 County Court Long Stay 3 9 /Stop l Cruise Cana 2 BMI Hospital University 10 Hospital of Cumbria visitors 1 11 A B C D E F G H AB CDEFG H ATTRACTIONS IN AND Assembly Rooms The Storey Salt Ayre Leisure Centre AROUND LANCASTER Built in 1759, the emporium houses Home to Lancaster Visitor Information Swimming pool, Energy soft play, an eclectic mix of stalls and a café. Centre and Printroom Café & Bar plus X-Height climbing, sports hall, Gravity Lancaster Castle event programme, gallery, workspaces flight tower, Tranquil Spa, Refuel Café. King Street, Lancaster, LA1 1LG and rooms for hire, garden and orchard. Take a guided tour and step into a 01524 414251 Doris Henderson Way, Lancaster, thousand years of history. www.lancaster.gov.uk/assemblyrooms Meeting House Lane, Lancaster, LA1 1TH LA1 5JS, 01524 847540 www.lancaster.gov.uk/saltayre Castle Park, Lancaster, LA1 1YJ Tuesday–Saturday 10:00 - 17:30 - The Storey 01524 64998 Sundays & Easter, May and August Bank 01524 582392, thestorey.co.uk Monday–Friday 06:00 - 21:30 www.lancastercastle.com Holidays 11:30 - 16:00 Monday–Saturday 08:30 – 21:00 Saturday 08:00 - 19:00 Sunday 08:00 - 18:30 Castle Grounds open 09:30 – 17:00 daily - Printroom Café & Bar Guided tours 10:00 – 15:15/15:45 King Street Studios Monday-Friday 08:30 - 18:00 Tour times/routes subject to change. -

Map, Attractions & Accommodation

Map, Attractions & Accommodation 111 & Heysham to Lancaster City Park & Ride 10 to Crook O’Lune, 2 Skerton t River Lune Millennium Park and Lune Aqueduct Bulk Stree 9 Retail Park 3 Quay Meadow re Ay en re e Park G kat S 8 4 Retail Park Superstore Vicarage Field Buses & Taxis . only D R 7 Escape H Room RT NO Long 5 Stay Buses & Taxis only Kanteena 6 Cinema LANCASTER VISITOR Long INFORMATION CENTRE Moor 6 Space Stay e Gregson Th rket Street Centre Storey Ma Bashful Alley Sir Simons Arcade 5 Charter Market Assembly Rooms Emporium Long 7 Stay Long Stay Buses & Taxis 4 only Magistrates Court and 8 County Court Long Stay 3 9 /Stop l Cruise Cana 2 BMI Hospital University 10 Hospital of Cumbria visitors 1 11 A B C D E F G H AB CDEFG H ATTRACTIONS IN AND Assembly Rooms Emporium The Storey Lancaster Arts at AROUND LANCASTER Built in 1759, this Emporium houses Home to Lancaster Visitor Information Lancaster University an eclectic mix of stalls. Centre and Printroom Café & Bar plus Exhibitions, music, theatre, dance, Lancaster Castle event programme, gallery, workspaces comedy, workshops, talks and more. King Street, Lancaster, LA1 1JN and rooms for hire, garden and orchard. Take a guided tour and step into a 01524 414251 Bailrigg, Lancaster University, LA1 4YW thousand years of history. www.lancaster.gov.uk/assemblyrooms Meeting House Lane, Lancaster, LA1 1TH 01524 594151, www.lancasterarts.org Castle Park, Lancaster, LA1 1YJ Monday: Closed - The Storey - Peter Scott Gallery 01524 64998 Tuesday–Saturday 10:00 - 17:30 01524 582392, thestorey.co.uk Mon-Fri 12:00 - 17:00 during exhibitions www.lancastercastle.com Sundays & Bank Holidays Easter-August Monday–Saturday 08:30 – 19:00 11:00 - 16:00 - Nuffield Theatre and Great Hall Castle Grounds open 09:30 – 17:00 daily - Printroom Café & Bar For event times please see website. -

Collections Development Policy Lancaster City Museums

Accreditation Scheme for Museums and Galleries in the United Kingdom Collections development policy Lancaster City Museums 2014 Reprinted November 2018 Name of museum: Lancaster City Museums (Lancaster City Museum, Maritime Museum, Cottage Museum) Name of governing body: Lancaster City Council Date on which this policy was approved by governing body: Insert date. Policy review procedure: The collections development policy will be published and reviewed from time to time, at least once every five years. Date at which this policy is due for review: July 2024 Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the collections development policy, and the implications of any such changes for the future of collections. 1 Relationship to other relevant policies/ plans of the organisation: 1.1 The museum’s statement of purpose is: Vision This is a place where the past is part of a thriving future Mission We will employ an entrepreneurial approach to our museums, to promote our rich heritage. We will be at the heart of the District’s cultural offering and we will inspire a feeling of ownership amongst our local communities. 1.2 The governing body will ensure that both acquisition and disposal are carried out openly and with transparency. 1.3 By definition, the museum has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. The governing body therefore accepts the principle that sound curatorial reasons must be established before consideration is given to any acquisition to the collection, or the disposal of any items in the museum’s collection. -

Quarter Sessions Building in Lancashire, 1770‒1830

Christopher Chalklin, ‘Quarter Sessions building in Lancashire, 1770–1830’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. X, 2000, pp. 92–121 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2000 QUARTER SESSIONS BUILDING IN LANCASHIRE, – CHRISTOPHER CHALKLIN etween about and expenditure on THE JUSTICES AT Bbuilding and construction by Lancashire was QUARTER SESSIONS among the largest for any English county. In the Until nearly the end of the eighteenth century only previous century there had been a steadily rising the gaol at Lancaster (used as in other counties to hold outlay, entirely on bridges apart from occasional prison debtors, those awaiting trial, and convicts) and at first repairs. Although Lancashire is the sixth largest three, later five bridges, and a raised roadway, were English county, the great growth of expenditure from the financial responsibility of the county. The number the s was particularly the result of the increase of of its bridges then rose, reaching by the early s. population. It more than trebled between and The two bridewells, or houses of correction, holding , and grew more than four times between and minor offenders and vagrants who were expected to . The estimated population of Lancashire between work for up to a few months, were financed separately . and was as follows. : ,; : The Preston bridewell was paid for by the five , or , ; : ,; : ,, . hundreds of Lonsdale, Amounderness, Blackburn, While population was growing all over Lancashire , Leyland and West Derby, and the Manchester prison the increase was especially great in the part of the by the other hundred, Salford. The six hundreds county from Preston and Blackburn southwards on were also responsible for about bridges, the account of the expansion of the cotton industry.