Lancaster District Heritage Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster-Cultural-Heritage-Strategy

Page 12 LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY REPORT FOR LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL Page 13 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................3 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................7 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................10 3 RECENT VISIONING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 24 4 HOW LANCASTER COMPARES AS A HERITAGE CITY...............28 5 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S BUILT FABRIC .....................................32 6 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S CULTURAL HERITAGE ATTRACTIONS39 7 THE MANAGEMENT OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 48 8 THE MARKETING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE.....51 9 CONCLUSIONS: SWOT ANALYSIS................................................59 10 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES FOR LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE .......................................................................................65 11 INVESTMENT OPTIONS..................................................................67 12 OUR APPROACH TO ASSESSING ECONOMIC IMPACT ..............82 13 TEN YEAR INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK .......................................88 14 ACTION PLAN ...............................................................................107 APPENDICES .......................................................................................108 2 Page 14 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lancaster is widely recognised -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

An Award Winning, Executive Development of 3, 4 and 5 Bedroom Properties from Story Homes

HIGH WOOD lancaster An award winning, executive development of 3, 4 and 5 bedroom properties from Story Homes. HIGH WOOD lancaster Welcome to Some images are courtesy of www.golakes.co.uk High Wood High Wood is an award winning development, having recently won a prestigious 5 star award for ‘Best Residential development in Lancashire’. This popular development boasts a stylish mix of 3, 4 and 5 bedroom family homes in a scenic and peaceful setting and features a network of cyclepaths and footpaths. High Wood has been designed with the outdoors in mind, making use of the vast open space and established greenery in the surrounding area, and offers seclusion and an element of countryside living while remaining close enough to the hub of the city. HIGH WOOD lancaster High Wood is set in a beautiful location, approached by it’s own tree lined avenue HIGH WOOD lancaster HIGH WOOD lancaster A charming city The charming city of Lancaster is the ideal place for Story Homes’ development of high quality and high specification, executive homes. As well as boasting beautiful scenery and stunning views, Lancaster offers the perfect environment for family living. Although only a small city, it is big on history and the cathedral, castle and cobbled streets certainly add to its beauty. The city’s past comes to life through these historic landmarks where you can explore the history of the city and its rich industrial and cultural past. HIGH WOOD lancaster Time to relax It’s easy to relax in Lancaster.... a pedestrianised centre offers boutique shops to browse, high street stores aplenty and quirky ‘off the beaten track’ coffee shops, which are ideal for enjoying local homemade cakes and other foody delights. -

The First 40 Years

A HISTORY OF LANCASTER CIVIC SOCIETY THE FIRST 40 YEARS 1967 – 2007 By Malcolm B Taylor 2009 Serialization – part 7 Territorial Boundaries This may seem a superfluous title for an eponymous society, so a few words of explanation are thought necessary. The Society’s sometime reluctance to expand its interests beyond the city boundary has not prevented a more elastic approach when the situation demands it. Indeed it is not true that the Society has never been prepared to look beyond the City boundary. As early as 1971 the committee expressed a wish that the Society might be a pivotal player in the formation of amenity bodies in the surrounding districts. It was resolved to ask Sir Frank Pearson to address the Society on the issue, although there is no record that he did so. When the Society was formed, and, even before that for its predecessor, there would have been no reason to doubt that the then City boundary would also be the Society’s boundary. It was to be an urban society with urban values about an urban environment. However, such an obvious logic cannot entirely define the part of the city which over the years has dominated the Society’s attentions. This, in simple terms might be described as the city’s historic centre – comprising largely the present Conservation Areas. But the boundaries of this area must be more fluid than a simple local government boundary or the Civic Amenities Act. We may perhaps start to come to terms with definitions by mentioning some buildings of great importance to Lancaster both visually and strategically which have largely escaped the Society’s attentions. -

The Story of a Man Called Daltone

- The Story of a Man called Daltone - “A semi-fictional tale about my Dalton family, with history and some true facts told; or what may have been” This story starts out as a fictional piece that tries to tell about the beginnings of my Dalton family. We can never know how far back in time this Dalton line started, but I have started this when the Celtic tribes inhabited Britain many yeas ago. Later on in the narrative, you will read factual information I and other Dalton researchers have found and published with much embellishment. There also is a lot of old English history that I have copied that are in the public domain. From this fictional tale we continue down to a man by the name of le Sieur de Dalton, who is my first documented ancestor, then there is a short history about each successive descendant of my Dalton direct line, with others, down to myself, Garth Rodney Dalton; (my birth name) Most of this later material was copied from my research of my Dalton roots. If you like to read about early British history; Celtic, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Normans, Knight's, Kings, English, American and family history, then this is the book for you! Some of you will say i am full of it but remember this, “What may have been!” Give it up you knaves! Researched, complied, formated, indexed, wrote, edited, copied, copy-written, misspelled and filed by Rodney G. Dalton in the comfort of his easy chair at 1111 N – 2000 W Farr West, Utah in the United States of America in the Twenty First-Century A.D. -

Page 2 of 24

“B.a.c.l.” Concert List for Choral and Orchestral Events in the Bay Region. “B.a.c.l.” Issue 48 (North Lancashire – Westmorland - Furness) Issue 47 winter 2018 - 19 “Bay area Early winter 2018 Anti Clash List” Welcome Concert Listing for Choral and Orchestral Concerts in the Bay Region Hi everyone , and welcome to the 4 8 issue of B.a.c.l. for winter of 20 18 /19 covering 11/11/2018 bookings received up to end of October . T his issue is a full issue and brings you up to date as at 1 st of November 2018. The “Spotlight” is on “ Lancaster Priory Music Events ” for which I would like to thank This quarter the Spotlight is on the “ Lancaster Priory Music Events ” Stephanie Edwards. Please refer to Page six which has two forms that could be run off and used for applying to sing in the Cumbria Festival Chorus on New Year’s Eve at Carver Uniting Church, Lake Road, Windermere at 7:00 p.m. and the Mary Wakefield Festival Opening concert on 23rd March 2019. “ A Little Taste of Sing Joyfully! ” You are invited to “ Come and enjoy singing ” with a lovely, welcoming choir ” , Sing Joyfully!” Music from the English Renaissance and well - loved British Folk Songs this term ; r ehearsals Tuesday January 8th (and subsequent Tuesdays until late March) 7:30 - 9pm Holy Trinity Church, Casterton . Sounds inviting! For more details please email [email protected] or telephone 07952 601568 . If anyone would like to publicize concerts by use of their poster, in jpeg format , please forward them to me and I’ll set up a facility on the B.a.c.l. -

FOB Walking Maps 2007.Qxd

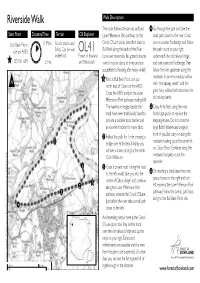

Riverside Walk Walk Description The route follows the tarmac surfaced 4 Go through the gate and take the Start Point Distance/Time Terrain OS Explorer Lune Millennium Park pathway to the small path down to the river. Cross Bull Beck Picnic 5 Miles Roads, tracks and Crook O’Lune picnic area, then back to over a wooden footbridge and follow site on A683 fields. Can be wet OL41 Bull Beck along the bank of the River the path round to your right underfoot. ‘Forest of Bowland Lune over reasonably flat grazed pastures underneath the old railway bridge, SD 541 649 2 Hrs and Ribblesdale’ (which may be damp at times and are and over a second footbridge.Then susceptible to flooding after heavy rainfall). follow the river upstream along the 1 Park at Bull Beck Picnic site, just riverbank. In summer, rosebay willow N north east of Caton on the A683. herb (the ‘railway weed’) and the Cross the A683 and join the Lune great hairy willow herb dominate the Millennium Park pathway, heading left. old railway banks. The hawthorn hedges beside the 5 Cross Artle Beck using the new track have been traditionally ‘layed’ to footbridge, put in to replace the provide a durable stock barrier and stepping-stones. Do not cross the an excellent habitat for many birds. large British Waterways bridge in 2 Follow this path for 1 mile crossing a front of you, but carry on along the 5 bridge over Artle Beck. Nearby you riverbank looking up at the windmills will see a stone carving by the artist on Caton Moor. -

Log of Hornby School 1900-87

Hornby School Log-Books 1900-94 The following are extracts from the school log books of Hornby, Lancs., between 1900 and 1994. They are a selection of the most interesting entries over those years. The log books were written by the Headteacher and there are four of them covering this period. The original log books are kept at the school. I am very grateful to Mr.B.G.Wood, Headteacher 1983-94, for allowing me to borrow and make extracts from them. 1900 19th November The Thermometer at 9 o'clock this morning registered only 42 degrees. Fire was lighted at 7 but during the night there had been a very severe frost. Florence Goth who has been suffering for the last few day from earache was not able to attend to her duties. The New Time Table as approved by J.G.IIes HMI was brought into use this morning. 20th November There are still 15 children absent from School on account of Whooping Cough. 26th November Florence Goth has not yet returned to her duties, and it is now known that earache referred to on the opposite page is more correctly described as Mumps. This morning I find several cases of Mumps in the School, and some are absent on that account. Jane Smith is also beginning in the Mumps and ought not to be among the children. She will report herself to Mr Kay at the Central Classes this afternoon. Dr Bone the Medical Officer of Health recommends the closing of the School again indefinitely to stamp out the Mumps and the Whooping Cough. -

PLANNING and HIGHWAYS REGULATORY COMMITTEE Date

Committee: PLANNING AND HIGHWAYS REGULATORY COMMITTEE Date: MONDAY, 13 DECEMBER 2010 Venue: LANCASTER TOWN HALL Time: 10.30 A.M. A G E N D A 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Minutes of the Meeting held on 15 November 2010 (previously circulated) 3 Items of Urgent Business authorised by the Chairman 4 Declarations of Interest Planning Applications for Decision Community Safety Implications In preparing the reports for this agenda, regard has been paid to the implications of the proposed developments on Community Safety issues. Where it is considered the proposed development has particular implications for Community Safety, this issue is fully considered within the main body of the report on that specific application. Category A Applications Applications to be dealt with by the District Council without formal consultation with the County Council. 5 A5 10/00456/CU Court View House, Aalborg Place, Duke's (Pages 1 - 5) Lancaster Ward Change of use of ground floor and first floor to further education college for EMBA College 6 A6 10/00610/FUL The Old Vicarage Retirement Upper Lune (Pages 6 - Home, 56 Main Street, Hornby Valley 23) Ward Erection of an extension to provide 15 new bedrooms, change of access and erection of new boundary wall for Forrester Retirement Home 7 A7 10/00611/LB The Old Vicarage Retirement Upper Lune (Pages 24 - Home, 56 Main Street, Hornby Valley 31) Ward Listed building consent for the erection of an extension to provide 15 new bedrooms, change of access and erection of new boundary wall for Forrester Retirement Home 8 A8 10/01012/VCN -

Overtown Cable, Overtown, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire

Overtown Cable, Overtown, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire Archaeological Watching Brief Report Oxford Archaeology North May 2016 Electricity North West Issue No: 2016-17/1737 OA North Job No: L10606 NGR: SD 62944 76236 to SD 63004 76293 Overtown Cable, Overtown, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire: Archaeological Watching Brief 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Circumstances of Project .................................................................................... 4 1.2 Location, Topography and Geology ................................................................... 4 1.3 Historical and Archaeological Background ........................................................ 4 2. METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Project Design ..................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Watching Brief .................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Archive ................................................................................................................ 6 3. WATCHING BRIEF RESULTS ..................................................................................... -

Good News for You and Your Family

A 4-star council Awarded top marks by the Audit Commission August 2007 DOG DAY SUMMERSSTUDENT FINANCE UP YOUR STREET Children rise to Kipper Visit our helpful Detectives’ hit the dog’s challenge roadshow this month and run case Page 8 Page 3 page 7 County steps up to new fight LANCASHIRE County Council has welcomed moves to extend economic opportunity for all. New responsibilities for councils were announced by Whitehall recently. Future prosperity depends on a reinvigora- tion of the area’s economy. And that means there 50,000 jobs • support for a high-tech future must be an effective way of working with business to • transforming East Lancashire • tourism and better support future busi- ness growth. rural development • new business parks County Councillor Hazel Harding, Lancashire County Council leader, said: “We believe that Lancashire’s local authori- Good news for you ties have the working knowledge to empower businesses and communi- ties in regeneration from a and your family grassroots level. “The county council has this theme at the heart of its Corporate Strategy and economy of our area to grow identified six key A NEW blueprint for its role in the Lancashire Lancashire has been even further.” priorities: I Partnerships’ Local Area unveiled which aims The Lancashire The redevelop- Agreement.” to create 50,000 jobs Economic Strategy aims to ment of Preston The review will require in just three years. regenerate deprived areas, as the North all councils in Lancashire establish new business West’s third city to look at the way they The plan aims to make parks, boost higher educa- I Transforming Preston into the North work together to support tion and training; and East Lancashire economic growth. -

Riverside Walk OL41 Start Point Distance/Time Terrain Public Transport Key to Facilities Bull Beck Picnic Site on A683 4 Miles Roads, Tracks and Fields

OS Explorer Riverside Walk OL41 Start Point Distance/Time Terrain Public transport Key to Facilities Bull Beck Picnic site on A683 4 Miles Roads, tracks and fields. Bus Services 80, 81, 81A, 81B Post Office, Toilets, Can be wet underfoot. (Lancaster to Kirkby Pub, Shop SD 541 649 2 Hrs Lonsdale/Ingleton) GPS Waypoints (OS grid refs) N 1 SD 541 649 2 SD 538 649 3 SD 534 648 4 SD 522 647 5 SD 532 655 6 SD 539 652 5 6 1 2 3 4 © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved (100023320) (2010) © Copyright. Crown 0 Miles 0.5 Mile 0 Km 1 Km www.forestofbowland.com Riverside Walk Walk Description About This Walk The route follows the tarmac surfaced 3 GPS: SD 534 648 5 GPS: SD 532 655 Caton and Brookhouse are situated on Lune Millennium Park pathway to the Cross a private road (taking the road to Cross Artle Beck using the new the north-facing slope of the Lune Crook O’Lune picnic area, then back to the left would take you into the centre footbridge, put in to replace the Valley. The villages lie in a scenic area Bull Beck along the bank of the River of Caton village) and continue along the stepping-stones. Do not cross the large near the celebrated Crook O’Lune - Lune over reasonably flat grazed Lune Millennium Park pathway towards British Waterways bridge in front of you, painted by Turner, praised by the poets pastures (which may be damp at times the Crook O’Lune. Just before the river but carry on along the riverbank looking Thomas Gray and William and are susceptible to flooding after take a small path down to the left.