Page 18 Vol. 39, No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

References Please Help Making This Preliminary List As Complete As Possible!

Cypraeidae - important references Please help making this preliminary list as complete as possible! ABBOTT, R.T. (1965) Cypraea arenosa Gray, 1825. Hawaiian Shell News 14(2):8 ABREA, N.S. (1980) Strange goings on among the Cypraea ziczac. Hawaiian Shell News 28 (5):4 ADEGOKE, O.S. (1973) Paleocene mollusks from Ewekoro, southern Nigeria. Malacologia 14:19-27, figs. 1-2, pls. 1-2. ADEGOKE, O.S. (1977) Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Ewekoro Formation (Paleocene) of southeastern Nigeria. Bulletins of American Paleontology 71(295):1-379, figs. 1-6, pls. 1-50. AIKEN, R. P. (2016) Description of two undescribed subspecies and one fossil species of the Genus Cypraeovula Gray, 1824 from South Africa. Beautifulcowries Magazine 8: 14-22 AIKEN, R., JOOSTE, P. & ELS, M. (2010) Cypraeovula capensis - A specie of Diversity and Beauty. Strandloper 287 p. 16 ff AIKEN, R., JOOSTE, P. & ELS, M. (2014) Cypraeovula capensis. A species of diversity and beauty. Beautifulcowries Magazine 5: 38–44 ALLAN, J. (1956) Cowry Shells of World Seas. Georgian House, Melbourne, Australia, 170 p., pls. 1-15. AMANO, K. (1992) Cypraea ohiroi and its associated molluscan species from the Miocene Kadonosawa Formation, northeast Japan. Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum 19:405-411, figs. 1-2, pl. 57. ANCEY, C.F. (1901) Cypraea citrina Gray. The Nautilus 15(7):83. ANONOMOUS. (1971) Malacological news. La Conchiglia 13(146-147):19-20, 5 unnumbered figs. ANONYMOUS. (1925) Index and errata. The Zoological Journal. 1: [593]-[603] January. ANONYMOUS. (1889) Cypraea venusta Sowb. The Nautilus 3(5):60. ANONYMOUS. (1893) Remarks on a new species of Cypraea. -

Cypraea Clandestina Candida.Pdf

Another example of forgery in Malacology: Pease's Cypraea candida arbitrarily used to serve personal interests of 'malacologists' by MC van Veen, April 2019 In this example I would like to focus on the usage of Cypraea candida which was described by Pease in 1865 [1]. Today, WoRMS classified it as a variety of Cypraea clandestina, a species that was described by Linnaeus in 1767 Nowadays the genus has changed into Palmadusta, so officially it becomes Palmadusta clandestina. But the genus name not so important, what is important however is the classification of Pease's Cypraea candida. WoRMS shows the name Palmadusta clandestina candida (Pease, 1865). Again, here you can see it is below the species level, the third name indicates subspecies, sometimes the third name indicates a variety or a form. This is the system: Genus name – Species name – Subspecies name. Below is a copy of Pease's description: The translation is: Cypraea candida Shell elongated-oval, completely white, the somewhat thickened sides rounded, rounded at the base; the extremities scarcely produced, slightly bent; lengthwise very thinly striated; The opening slightly bent, teeth strong and somewhat spaced, interstices (between the teeth) deeply cut. Length 15 mm, width 8 mm. The question arises how malacologists were ever able to conclude that Cypraea candida should be a special variety of Palmadusta/Cypraea clandestina. There are no features in the text that set it apart from the normal clandestina because the text only describes common characteristics of the species; there isn't any comparison whatsoever. Furthermore, Pease's description isn't even conclusive regarding the species! Even though the Cypraea candida shell only measured 15 mm, it could well be that the all white Cypraea eburnea is indicated, even though eburnea is often larger than 35 mm. -

The Marine Zoologist, Volume 1, Number 7, 1959

The Marine Zoologist, Volume 1, Number 7, 1959 Item Type monograph Publisher Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales Download date 23/09/2021 18:13:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32615 TI I LIBRAR THE MARINE ZOOLOGIST Vol 1. No.". Sydney, September 18, -1959 Donated by BAMFIELD MARINE STATION Dr. Ian McTaggart Cowan ~~THE some of the molluscs these were replaced as soon as the "danger" had MARINE ZOOLOGIST" passed. Owing to the darkness and depth of water it was difficult to make detailed observations of parental care. The mother used her siphon to Vol. 1. No.7. squirt water over the eggs, and her tentacles were usually weaving in and out among the egg-strings. The same thing was observed with the female in (Incorporated with the Proceedings of the Royal Zoological Society of April 1957, and Le Souef & Allan recorded the fact in some detail in New South Wales, 1957-58, published September 18, 1959.) 1933 and 1937. Unfortunately on 29th October 1957 the tank had to be emptied and cleaned and the octopus was released into the sea in a rather weak state. Her "nest" was destroyed and the eggs removed and examined. It came as a surprise to find that hatching had commenced and was progressing at a rapid rate because the eggs examined on 8th October showed little sign Some Observations on the Development of Two of development and it was believed that, as reported by Le Souef & Allan (1937), 5-6 weeks had to elapse between laying and hatching. -

THE LISTING of PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T

August 2017 Guido T. Poppe A LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS - V1.00 THE LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T. Poppe INTRODUCTION The publication of Philippine Marine Mollusks, Volumes 1 to 4 has been a revelation to the conchological community. Apart from being the delight of collectors, the PMM started a new way of layout and publishing - followed today by many authors. Internet technology has allowed more than 50 experts worldwide to work on the collection that forms the base of the 4 PMM books. This expertise, together with modern means of identification has allowed a quality in determinations which is unique in books covering a geographical area. Our Volume 1 was published only 9 years ago: in 2008. Since that time “a lot” has changed. Finally, after almost two decades, the digital world has been embraced by the scientific community, and a new generation of young scientists appeared, well acquainted with text processors, internet communication and digital photographic skills. Museums all over the planet start putting the holotypes online – a still ongoing process – which saves taxonomists from huge confusion and “guessing” about how animals look like. Initiatives as Biodiversity Heritage Library made accessible huge libraries to many thousands of biologists who, without that, were not able to publish properly. The process of all these technological revolutions is ongoing and improves taxonomy and nomenclature in a way which is unprecedented. All this caused an acceleration in the nomenclatural field: both in quantity and in quality of expertise and fieldwork. The above changes are not without huge problematics. Many studies are carried out on the wide diversity of these problems and even books are written on the subject. -

CONE SHELLS - CONIDAE MNHN Koumac 2018

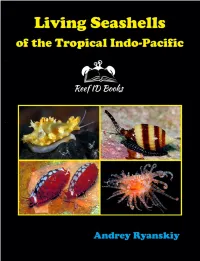

Living Seashells of the Tropical Indo-Pacific Photographic guide with 1500+ species covered Andrey Ryanskiy INTRODUCTION, COPYRIGHT, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION Seashell or sea shells are the hard exoskeleton of mollusks such as snails, clams, chitons. For most people, acquaintance with mollusks began with empty shells. These shells often delight the eye with a variety of shapes and colors. Conchology studies the mollusk shells and this science dates back to the 17th century. However, modern science - malacology is the study of mollusks as whole organisms. Today more and more people are interacting with ocean - divers, snorkelers, beach goers - all of them often find in the seas not empty shells, but live mollusks - living shells, whose appearance is significantly different from museum specimens. This book serves as a tool for identifying such animals. The book covers the region from the Red Sea to Hawaii, Marshall Islands and Guam. Inside the book: • Photographs of 1500+ species, including one hundred cowries (Cypraeidae) and more than one hundred twenty allied cowries (Ovulidae) of the region; • Live photo of hundreds of species have never before appeared in field guides or popular books; • Convenient pictorial guide at the beginning and index at the end of the book ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The significant part of photographs in this book were made by Jeanette Johnson and Scott Johnson during the decades of diving and exploring the beautiful reefs of Indo-Pacific from Indonesia and Philippines to Hawaii and Solomons. They provided to readers not only the great photos but also in-depth knowledge of the fascinating world of living seashells. Sincere thanks to Philippe Bouchet, National Museum of Natural History (Paris), for inviting the author to participate in the La Planete Revisitee expedition program and permission to use some of the NMNH photos. -

Cowry Shell Money and Monsoon Trade: the Maldives in Past Globalizations

Cowry Shell Money and Monsoon Trade: The Maldives in Past Globalizations Mirani Litster Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Australian National University 2016 To the best of my knowledge the research presented in this thesis is my own except where the work of others has been acknowledged. This thesis has not previously been submitted in any form for any other degree at this or any other university. Mirani Litster -CONTENTS- Contents Abstract xv Acknowledgements xvi Chapter One — Introduction and Scope 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 An Early Global Commodity: Cowry Shell Money 4 1.2.1 Extraction in the Maldives 6 1.2.2 China 8 1.2.3 India 9 1.2.4 Mainland Southeast Asia 9 1.2.5 West and East Africa 10 1.3 Previous Perspectives and Frameworks: The Indian Ocean 11 and Early Globalization 1.4 Research Aims 13 1.5 Research Background and Methodology 15 1.6 Thesis Structure 16 Chapter Two — Past Globalizations: Defining Concepts and 18 Theories 2.1 Introduction 18 2.2 Defining Globalization 19 2.3 Theories of Globalization 21 2.3.1 World Systems Theory 21 2.3.2 Theories of Global Capitalism 24 2.3.3 The Network Society 25 2.3.4 Transnationality and Transnationalism 26 2.3.5 Cultural Theories of Globalization 26 2.4 Past Globalizations and Archaeology 27 2.4.1 Globalization in the Past: Varied Approaches 28 i -CONTENTS- 2.4.2 Identifying Past Globalizations in the Archaeological 30 Record 2.5 Summary 32 Chapter Three — Periods of Indian Ocean Interaction 33 3.1 Introduction 33 3.2 Defining the Physical Parameters 34 3.2.1 -

Research Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 9, Issue, 01, pp.45366-45369, January, 2017 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE A STUDY ON DIVERSITY OF MOLLUSCS IN NEIL ISLANDS *,1Priyankadevi, 2Revathi, K., 3Senthil Kumari, S., 3Subashini, A. and 4Raghunathan, C. 1Guru Nanak College, Chennai 2Ethiraj College for Women, Chennai 3Chellammal Women’s College, Chennai 4Zoological Survey of India, A&NRC, Port Blair ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The Andaman sea Eco region is biologically rich in both diversity and abundance. The high diversity is encountered from genus to individual species, habitat and ecosystems. The coral reefs, mangroves, sea grass beds, Received 29th October, 2016 marine lakes and deep sea valleys of the region form a constellation of diverse habitat that support a spectacular Received in revised form variety of fauna. Molluscsare highly successful invertebrates in terms of ecology and adaptation and are found 28th November, 2016 nearly in all habitats ranging from deepest ocean trenches to the intertidal zones, and freshwater to land occupying Accepted 07th December, 2016 a wide range of habitats. Much of the molluscan diversity occurs in the tropical world. Despite this great diversity, Published online 31st January, 2017 very few studies on molluscs have been carried out in the tropical world. An attempt was made to study the diversity and distribution of molluscs along the intertidal regions of Neil islands. During the survey three different Key words: beaches of Neil Island were selected, named, Sitapurbeach, Laxmanpur beach and Bharatpur beach. The study area is located 37 kms to lies in the northern part of south of the Andaman Islands. -

Barycypraea Teulerei(Cazenavette, 1845

Biodiversity Journal , 2016, 7 (1): 79–88 MONOGRAPH Barycypraea teulerei (Cazenavette, 1845) (Gastropoda Cypraeidae): a successful species or an evolutionary dead-end? Marco Passamonti Dipartimento di Scienze Biologiche Geologiche e Ambientali (BiGeA), Via Selmi 3, 40126 Bologna, Italy; email: marco. [email protected] ABSTRACT Barycypraea teulerei (Cazenavette, 1845) (Gastropoda Cypraeidae) is an unusual cowrie species, showing remarkable adaptations to an uncommon environment. It lives intertidally on flat sand/mud salt marshes, in a limited range, in Oman. On Masirah Island, humans probably drove it to extinction because of shell collecting. A new population, with a limited range, has recently been discovered, and this article describes observations I made on site in 2014. Evolution shaped this species into a rather specialized and successful life, but has also put it at risk. Barycypraea teulerei is well adapted to survive in its habitat, but at the same time is easily visible and accessible to humans, and this puts it at high risk of extinction. Evolution is indeed a blind watchmaker that ‘ has no vision, no foresight, no sight at all ’. And B. teulerei was just plain unlucky to encounter our species on its journey on our planet. KEY WORDS Cypraeidae; Barycypraea teulerei ; Biology; Evolution; Blind Watchmaker. Received 23.02.2016; accepted 22.03.2016; printed 30.03.2016 Proceedings of the Ninth Malacological Pontine Meeting, October 3rd-4th, 2015 - San Felice Circeo, Italy INTRODUCTION (Sowerby III, 1899) (Fig. 2). This genus is charac - terized by squat, heavy shells with a roughly trian - “Natural selection, the blind, unconscious, auto- gular/pyriform shape. The mantle is always thin and matic process which Darwin discovered, and which almost transparent, whitish or pale brown, with we now know is the explanation for the existence little ( B. -

(Gastropods and Bivalves) and Notes on Environmental Conditions of Two

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2014; 2 (5): 72-90 ISSN 2320-7078 The molluscan fauna (gastropods and bivalves) JEZS 2014; 2 (5): 72-90 © 2014 JEZS and notes on environmental conditions of two Received: 24-08-2014 Accepted: 19-09-2014 adjoining protected bays in Puerto Princesa City, Rafael M. Picardal Palawan, Philippines College of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, Western Philippines University Rafael M. Picardal and Roger G. Dolorosa Roger G. Dolorosa Abstract College of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, Western Philippines With the rising pressure of urbanization to biodiversity, this study aimed to obtain baseline information University on species richness of gastropods and bivalves in two protected bays (Turtle and Binunsalian) in Puerto Princesa City, Philippines before the establishment of the proposed mega resort facilities. A total of 108 species were recorded, (19 bivalves and 89 gastropods). The list includes two rare miters, seven recently described species and first record of Timoclea imbricata (Veneridae) in Palawan. Threatened species were not encountered during the survey suggesting that both bays had been overfished. Turtle Bay had very low visibility, low coral cover, substantial signs of ecosystem disturbances and shift from coral to algal communities. Although Binunsalian Bay had clearer waters and relatively high coral cover, associated fish and macrobenthic invertebrates were of low or no commercial values. Upon the establishment and operations of the resort facilities, follow-up species inventories and habitat assessment are suggested to evaluate the importance of private resorts in biodiversity restoration. Keywords: Binunsalian Bay, bivalves, gastropods, Palawan, species inventory, Turtle Bay 1. Introduction Gastropods and bivalves are among the most fascinating groups of molluscs that for centuries have attracted hobbyists, businessmen, ecologists and scientists among others from around the globe. -

![O Porcelankach Nie Z Porcelany [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8124/o-porcelankach-nie-z-porcelany-pdf-1528124.webp)

O Porcelankach Nie Z Porcelany [Pdf]

O porcelankach nie z porcelany Spośród wszystkich rodzin ślimaków morskich najbardziej popularne i cenione są porcelanki (Cypraeidae Rafinesque, 1815). Ich muszle, przypominające jajo ze spłaszczonym spodem przeciętym ząbkowanym szczelinowatym ujściem, w zależności od gatunku osiągają od 1 do 19 cm wysokości. Skrętka jest zazwyczaj niewidoczna, gdyż u dorosłych osobników obejmuje ją całkowicie ostatni skręt. Muszle porcelanek podziwiane są ze względu na gładką, błyszczącą powierzchnię, często pięknie ubarwioną i wzorzystą. Są one wytworami fałdów skórnych zwanych płaszczem, zaś ich podstawowym budulcem jest węglan wapnia w postaci aragonitu. Kiedy zwierzę jest aktywne, dwa fałdy płaszcza wysunięte z muszli całkowicie lub częściowo ją otaczają. To one wyznaczają kolorystyczny wzór muszli, reperują ją i powiększają, chronią przed przyrastaniem organizmów morskich oraz zabezpieczają jej błyszczącą powierzchnię, która staje się matowa, jeżeli pozostaje przez długi czas eksponowana w otaczającej wodzie. Od niepamiętnych czasów muszle porcelanek służą jako ozdoba i do wyrobu przedmiotów użytkowych. Były środkiem płatniczym, symbolem statusu społecznego i płodności. Znajdowane są w grobach kobiecych w Azji, Europie i w innych częściach świata. Pojedyncze egzemplarze niezwykle rzadkich gatunków, u schyłku ubiegłego wieku, miały wartość prawdziwych klejnotów. Ich cena na aukcjach światowych przekraczała 20 000 dolarów. Współcześnie rodzina porcelanek reprezentowana jest przez 251 gatunków zamieszkujących głównie morza tropikalne i subtropikalne obszaru indopacyficznego. Wiele gatunków jest powszechnie spotykanych na płytkowodnych rafach tropikalnych. Inne przystosowane są do życia w wodach umiarkowanych i/lub w środowiskach głębokowodnych (do 700 m głębokości). W Morzu Śródziemnym występuje tylko sześć gatunków. Porcelanki aktywne są głównie nocą, w dzień ukrywają się w zakamarkach skał i koralowców. Dorosłe osobniki gatunków mających duże i grube muszle 1 np. -

2000 Through 2009)

TRITON No 19 March 2009 Supplement 4 CONCHOLOGICAL INFORMATION PUBLISHED IN TRITON 1-19 (2000 THROUGH 2009) 2. AUTHOR INDEX This index is arranged in the alphabetical order. If there are several authors of a publication their names are listed exactly as in their works published. Prepared by E.L. Heiman 1 TRITON No 19 March 2009 Supplement 4 2. AUTHOR INDEX authors year article issue Bar Zeev, U & THE MICRO-SHELL COLLECTION OF KALMAN HERTZ IS DONATED TO 2006 14:6 Singer, S. TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY Bonomolo, G. & DESCRIPTION OF A NEW MURICID FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA: 2006 OCINEBRINA PADDEUI 13:1-4 Buzzurro G. (MOLLUSCA, GASTROPODA, MURICIDAE, OCENEBRINAE) Buzzurro, G. & 2008 UNCOMMON FORM OF EROSARIA TURDUS (LAMARCK, 1810) 17:24 Heiman, E.L. Buzzurro, G. 2005 FUSINUS ROLANI: A NEW MEDITERRANEAN SPECIES 11:1-3 & Ovalis, P. Buzzurro, G. & A NEW SPECIES OF ALVANIA 2007 (GASTROPODA:PROSOBRANCHIA:RISSOIDAE) FROM CROATIAN 15:5-9 Prkić, J. COASTS OF DALMATIA 2001 FUSINUS DALPIAZI (COEN, 1918), A CONTROVERSIAL SPECIES 4:1-3 NOTES AND COMMENTS ON THE MEDITERRANEAN SPECIES OF THE Buzzurro, G. GENUS DIODORA GRAY, 1821 2004 10:1-9 & Russo, P. (ARCHEOGASTROPODA:FISSURELLIDAE) WITH A DESCRIPTION OF A NEW SPECIES 2008 A NEW REPLACEMENT NAME FOR FUSUS CRASSUS PALARY, 1901 17:7 Chadad, H., Heiman, E.L. & 2007 A GIANT SHELLS OF MAURITIA ARABICA GRAYANA 15:10 M. Kovalis Charter M. & SNAILS IN PELLETS AND PREY REMAINS OF KESTRE (FALCO 2005 12:31-32 Mienis H.K. TINNUNCULUS) IN ISRAEL ADDITIONS TO THE KNOWLEDGE OF IACRA (BIVALVIA; SEMELIDAE) Dekker, H. -

The Cowries of the East African Coasts: Supplement II

The Cowries of the East African coasts: Supplement II. Item Type Journal Contribution Authors Verdcourt, B. Download date 02/10/2021 17:47:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/7224 "C" Page 130 Vol. XXIII. No; 3(100) THE COWRIES OF THE EAST AFRICAN COASTS SUPPLEMENT II By BERNARD VERDCOUR.T, B.SC., PH.D. (PLATE I opposite page 134) This supplement is based entirely on information supplied to me by various collectors. Since my paper· was published many persons have started collecting and have shown many of my original remarks concerning distribution and rarity to be completely erroneous. This is to be expected since my remarks were based entirely on the collections at my disposal; I have never collected at the coast myself. Additional comments are listed in the order of my original paper. Authorities for the names have been omitted save in cases where the species is new to the Kenya list. I have kept to the names used in my original paper and not followed recent changes. I am pleased to say that there is a distinct move towards dispensing with the large number of genera used in recent works. Miss Alison Kay of the University of Hawaii has found the evidence of anatomy to be directly opposed to the recognition of these genera and has proposed the return to Cypraea for all the members of the subfamily Cypraeinae (see Nature 180: 1436-1437 (1957). I have kept the nomenclature used in my original pamphlet merely to avoid confusion but recommend that we sholud return to using Cypraea and, for general collector's use, specific names alone will, of course, suffice.