“Bad Girls”: Transgressive Narratives and Rebellious Daughters in Contemporary British Jewish Women’S Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama Courtney Watson, Ph.D. Radford University Roanoke, Virginia, United States [email protected] ABSTRACT Cultural movements including #TimesUp and #MeToo have contributed momentum to the demand for and development of smart, justified female criminal characters in contemporary television drama. These women are representations of shifting power dynamics, and they possess agency as they channel their desires and fury into success, redemption, and revenge. Building on works including Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, dramas produced since 2016—including The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, and Killing Eve—have featured the rise of women who use rule-breaking, rebellion, and crime to enact positive change. Keywords: #TimesUp, #MeToo, crime, television, drama, power, Margaret Atwood, revenge, Gone Girl, Orange is the New Black, The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, Killing Eve Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 37 Watson From the recent popularity of the anti-heroine in novels and films like Gone Girl to the treatment of complicit women and crime-as-rebellion in Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale to the cultural watershed moments of the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, there has been a groundswell of support for women seeking justice both within and outside the law. Behavior that once may have been dismissed as madness or instability—Beyoncé laughing wildly while swinging a baseball bat in her revenge-fantasy music video “Hold Up” in the wake of Jay-Z’s indiscretions comes to mind—can be examined with new understanding. -

M E O R O T a Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (Formerly Edah Journal)

M e o r o t A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly Edah Journal) Tishrei 5770 Special Edition on Modern Orthodox Education CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction to Special Tishrei 5770 Edition Nathaniel Helfgot SYMPOSIUM On Modern Orthodox Day School Education Scot A. Berman, Todd Berman, Shlomo (Myles) Brody, Yitzchak Etshalom,Yoel Finkelman, David Flatto Zvi Grumet, Naftali Harcsztark, Rivka Kahan, Miriam Reisler, Jeremy Savitsky ARTICLES What Should a Yeshiva High School Graduate Know, Value and Be Able to Do? Moshe Sokolow Responses by Jack Bieler, Yaakov Blau, Erica Brown, Aaron Frank, Mark Gottlieb The Economics of Jewish Education The Tuition Hole: How We Dug It and How to Begin Digging Out of It Allen Friedman The Economic Crisis and Jewish Education Saul Zucker Striving for Cognitive Excellence Jack Nahmod To Teach Tsni’ut with Tsni’ut Meorot 7:2 Tishrei 5770 Tamar Biala A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah REVIEW ESSAY Rabbinical School © 2009 Life Values and Intimacy Education: Health Education for the Jewish School, Yocheved Debow and Anna Woloski-Wruble, eds. Jeffrey Kobrin STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Meorot: A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly The Edah Journal) Statement of Purpose Meorot is a forum for discussion of Orthodox Judaism’s engagement with modernity, published by Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School. It is the conviction of Meorot that this discourse is vital to nurturing the spiritual and religious experiences of Modern Orthodox Jews. Committed to the norms of halakhah and Torah, Meorot is dedicated -

A Tribu1e 10 Eslller, Mv Panner in Torah

gudath Israel of America's voice in kind of informed discussion and debate the halls of courts and the corri that leads to concrete action. dors of Congress - indeed every A But the convention is also a major where it exercises its shtadlonus on yardstick by which Agudath Israel's behalf of the Kial - is heard more loudly strength as a movement is measured. and clearly when there is widespread recognition of the vast numbers of peo So make this the year you ple who support the organization and attend an Agm:fah conventicm. share its ideals. Resente today An Agudah convention provides a forum Because your presence sends a for benefiting from the insights and powerfo! - and ultimately for choice aa:ommodotions hadracha of our leaders and fosters the empowering - message. call 111-m-nao is pleased to announce the release of the newest volume of the TlHllE RJENNlERT JED>JITJION ~7~r> lEN<ClY<ClUO>lPElOl l[}\ ~ ·.:~.~HDS. 1CA\J~YA<Gr M(][1CZ\V<Q . .:. : ;······~.·····················.-~:·:····.)·\.~~····· ~s of thousands we~ed.(>lig~!~d~ith the best-selling mi:i:m niw:.r c .THE :r~~··q<:>Jy(MANDMENTS, the inaugural volume of theEntzfl(lj)('dia (Mitzvoth 25-38). Now join us aswestartfromthebeginning. The En~yclop~dia provides yau with • , • A panciramicviewofthe entire Torah .Laws, cust9ms and details about each Mitzvah The pririlafy reasons and insights for each Mitzvah. tteas.. ury.· of Mid. ra. shim and stories from Cha. zal... and m.uc.h.. n\ ''"'''''' The Encyclopedia of the Taryag Mitzvoth The Taryag Legacy Foundation is a family treasure that is guaranteed to wishes to thank enrich, inspire, and elevate every Jewish home. -

Expanding the Jewish Feminist Agenda Judith Plaskow

Expanding the Jewish Feminist Agenda Judith Plaskow ewish feminists have succeeded in changing the task of religious feminists in the new millennium is to face of Jewish religious life in the United States end this counterproductive division of labor. How can J beyond the wildest dreams of those of us who, in we hope to soli* the gains of the last decades with- the late 1960s, began to protest the exclusion of women out sophisticated analyses of power in the Jewish com- from Jewish religious practice. Thirty years ago, munity and in the larger society? How do we begin to who could have anticipated that, at the turn of the theorize and act on the ways in which creating a more century, there would be hundreds of female rabbis just Judaism is but a small piece of the larger task of representing three Jewish denominations, untold creating a more just world? numbers of female Torah and Haftorah readers, and Jewish feminists have diffidtytransforming Jew- female cantors and service leaders in synagogues ish liturgy and integrating the insights of feminist throughout the country? scholarship into Jewish education not simply because Who could have imagined that so many girls of religious barriers but also because of lack of access would expect a full bat mitzvah as a matter of course, to power and money. A 1998 study commissioned by or that Orthodox women would be learning Talmud, Ma’yan, The Jewish Women’s Project in New York, mastering synagogue skills, and functioning as full documented the deplorable absence of women from participants in services of their own? the boards of major Jewish organizations. -

Off the Derech: a Selected Bibliography

Off the Derech: A Selected Bibliography Books Abraham, Pearl. Giving Up America (Riverhead Books, 1998). Deena and Daniel buy a house, but soon after their relationship disintegrates and Deena questions her marriage, her job and her other relationships. Abraham, Pearl. The Romance Reader (Riverhead Books, 1995). Twelve-year-old Rachel Benjamin strains against the boundaries as the oldest daughter in a very strict Hasidic family. Alderman, Naomi. Disobedience. (Viking, 2006). Ronit Krushka never fit into her Orthodox London neighborhood or life as the daughter of its rabbinic leader. After his death, she returns to the community and re-examines her relationships, including one with another woman. Alderman presents a literary, thought-provoking journey of growth and acceptance. Auslander, Shalom. Foreskin’s Lament. (Riverhead Books, 2007). Auslander’s memoir relates the childhood experiences and interactions in the Orthodox community that led to his anger with God and to charting his own path. His caustic wit leaves the reader simultaneously hysterical and shocked. Bavati, Robyn. Dancing in the Dark. (Penguin Australia 2010; Flux (USA), 2013). Yehudit, Ditty, Cohen pursues her dreams of ballet secretly because her strictly Orthodox family would not approve of this activity. As her natural talent grows, so does her guilt at deceiving her family. Chayil, Eishes. Hush (Walker & Company; 2010). Gittel’s best friend commits suicide when they are ten-years-old, and she must come to terms with Devoiry’s death and the community’s stance on sexual abuse to move forward in her own life. Fallenberg, Evan. Light Fell (Soho Press, 2008). After a homosexual affair, Joseph leaves his wife and five sons. -

THE Private RESIDENT Governess

THE -Y OR THE TIGER?: EVOLVING VICTORIAN PERCEOTIONS OF EDUCATION AND THE PRiVATE RESIDENT GOVeRNESS Elizabeth Dana Rescher A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English The University of Toronto G Copyright by Elizabeth Dana Rescher, 1999 National Library Bibliothéque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, nie W@lliigton OttawaON KlAON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copy~@tin this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de ceNe-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. TEE LADY OR THE TI-?: EVOLVING VfCTORlAW PERCEPTIONS OF EDUCATION MD TEE PRfVATE RESIDENT GOVBRNESS A thesis smrnitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English The University of Toronto by Elizabeth Dana Rescher, 1999 --Abattact-- From the first few decades of the nineteenth century to the 1860s, the governess-figure moved steadily in public estimation from embodiment of pathos to powerful subverter of order, only to revert in the last decades of the 1800s to earlier type. -

OMC | Data Export

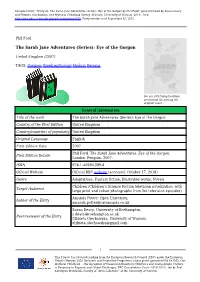

Amanda Potter, "Entry on: The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon by Phil Ford", peer-reviewed by Susan Deacy and Elżbieta Olechowska. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/550. Entry version as of September 25, 2021. Phil Ford The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon United Kingdom (2007) TAGS: Gorgons Greek mythology Medusa Perseus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon Country of the First Edition United Kingdom Country/countries of popularity United Kingdom Original Language English First Edition Date 2007 Phil Ford. The Sarah Jane Adventures: Eye of the Gorgon. First Edition Details London: Penguin, 2007. ISBN 978-1-40590-399-8 Official Website Official BBC website (accessed: October 17, 2018) Genre Adaptations, Fantasy fiction, Illustrated works, Novels Children (Children’s Science Fiction television novelization, with Target Audience large print and colour photographs from the television episodes) Amanda Potter, Open University, Author of the Entry [email protected] Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, [email protected] Peer-reviewer of the Entry Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. -

![Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4839/sexuality-is-fluid-1-a-close-reading-of-the-first-two-seasons-of-the-series-analysing-them-from-the-perspectives-of-both-feminist-theory-and-queer-theory-264839.webp)

Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory

''Sexuality is fluid''[1] a close reading of the first two seasons of the series, analysing them from the perspectives of both feminist theory and queer theory. It or is it? An analysis of television's The L Word from the demonstrates that even though the series deconstructs the perspectives of gender and sexuality normative boundaries of both gender and sexuality, it can also be said to maintain the ideals of a heteronormative society. The [1]Niina Kuorikoski argument is explored by paying attention to several aspects of the series. These include the series' advertising both in Finland and the ("Seksualność jest płynna" - czy rzeczywiście? Analiza United States and the normative femininity of the lesbian telewizyjnego "The L Word" z perspektywy płci i seksualności) characters. In addition, the article aims to highlight the manner in which the series depicts certain characters which can be said to STRESZCZENIE : Amerykański serial telewizyjny The L Word stretch the normative boundaries of gender and sexuality. Through (USA, emitowany od 2004) opowiada historię grupy lesbijek this, the article strives to give a diverse account of the series' first two i biseksualnych kobiet mieszkających w Los Angeles. Artykuł seasons and further critical discussion of The L Word and its analizuje pierwsze dwa sezony serialu z perspektywy teorii representations. feministycznej i teorii queer. Chociaż serial dekonstruuje normatywne kategorie płci kulturowej i seksualności, można ______________________ również twierdzić, że podtrzymuje on ideały heteronormatywnego The analysis in the article is grounded in feminist thinking and queer społeczeństwa. Przedstawiona argumentacja opiera się m. in. na theory. These theoretical disciplines provide it with two central analizie takich aspektów, jak promocja serialu w Finlandii i w USA concepts that are at the background of the analysis, namely those of oraz normatywna kobiecość postaci lesbijek. -

The Tifereth Israel

THE TIFERETH ISRAEL January/FebruaryFORUM 2019 | Teiveit/Sh’vat/Adar I 5779 Tu Bishvat: The Birthday of the Trees Monday, January 21, 2019 Inclusion Shabbat Shabbat Service Schedule Jan. 4 & Feb. 1 I 7:30 pm I Katz Chapel Va’era January 4-5/28 Teiveit A warm and meaningful Kabbalat Friday Evening Service 6:00 pm Shabbat for people and families with Inclusion Shabbat 7:30 pm special needs. All are welcome. For more Shabbat Warmup – ShabbaTunes 9:00 am information, contact Helen Miller at Shabbat Morning Service 9:30 am 614-236-4764. Young Peoples’ Synagogue 10:30 am Boker Tov Shabbat 11:00 am Bo January 11-12/6 Sh’vat Boker Tov Shabbat Friday Evening Service 6:00 pm Jan. 5 & Feb. 2 I 11:00 am I Katz Chapel Shabbat Warmup – Torah Talks Parsha Study 9:00 am A special Shabbat celebration for children Shabbat Morning Service - Gabrielle Schiff, bat mitzvah 9:30 am up to age 5 and their grown-ups. For more Young Peoples’ Synagogue 10:30 am information, contact Morgan at 614-928- 3286 or [email protected]. B’shalach - Anniversary Shabbat January 18-19/13 Sh’vat Wine & Cheese Oneg 5:30 pm Shabbat Neshamah: Friday Evening Musical Mindfulness Service 6:00 pm Shabbat Neshamah Shabbat Warmup – Shabbat Stretch: Light Yoga & Mindfulness 9:00 am Shabbat Morning Service - Shabbat Shira & Chelsea Wasserstrom, 9:30 am Jan. 18 & Feb. 15 I 6:00 pm I Katz Chapel bat mitzvah Nurture your spirit with Kabbalat Young Peoples’ Synagogue 10:30 am Shabbat. We start getting in the Shabbat mood in the Atrium at 5:30 pm with some Yitro - Scholar-in-Residence Shabbat January 25-26/20 Sh’vat wine and cheese, generously sponsored Friday Evening Service 6:00 pm by Fran & Steve Lesser, before moving Shabbat Dinner - by reservation 7:15 pm into the chapel for a service filled with Shabbat Warmup – Mah Chadash: What's News in Israel 9:00 am Shabbat Morning Service - sermon by Scholar in Residence 9:30 am singing, poetry, prayer, and meditation. -

William Hulme's Grammar School

WILLIAM HULME’S GRAMMAR SCHOOL Activities Room Entrance Disabled parking overflow Science Building Lift Music Entrance Room Entrance Stairs School from Hall Car Park Manchester Main Entrance Pedestrian Entrance Registration k s Day Limmud e Dining Room D p l S e p H r STAIRS TO i n g D ROOMS B STAIRS TO r i d D ROOMS 2019 g e Shuk t n R t i r o Lift o u a Donner P o d c Sunday 30 June 2019 y l l l Building b a b m t William Hulme’s Grammar School e e n s s d A n Spring Bridge Road, Blue Badge Entrance u y o c Car Park Entrance r n G Whalley Range e g Young Limmud d r r a and crèche e Manchester M16 8PR H m B Performing E l u e Entrance Arts Centre B Zochonis a Entrance d g PAC Rooms Building e p a r Stairs k i n g Name To parking at Whalley Range High School Session Four 13:40 – 14:40 Session Five 15:00 – 16:00 Session Six 16:20 – 17:20 Who is a Jew in Africa? Extremism and Antisemitism Balloon Debate WHERE DO I GO FOR MY SESSION? Clive Lawton Louise Ellman Panel session Jews in American Sixties Culture Churchill and the Jews David Benkof Richard Cohen Ground Floor Dining Hall – Registration, Grab & Go Lunch, Tea and Coffee stations Entrance Hall – Helpdesk Is there such a thing as a really Palestinians or Jews? Whose land is it? good Kosher Wine? Geoffrey Ben-Nathan Shuk Jon Sussman Tea and Coffee station Creating Community through The Rosenbergs – A Tragedy Main Male, Female and Accessible Toilets What is Limmud Anyway? Common Values of the Cold War DONNER David Hoffman Eli Ovits Matthew Suher BUILDING First Floor m o The Myth of Jewish -

Is Judaism 'Sex Positive?'

Is Judaism ‘Sex Positive?’ Understanding Trends in Recent Jewish Sexual Ethics Rebecca Epstein-Levi Introduction hen I tell people that I am a scholar of Jewish sexual eth- Wics, I am sometimes asked just what Judaism has to say about the matter. I usually give the unhelpful academic refrain of “well, it’s complicated…” or I tell the well-worn joke about “two Jews, three opinions.” The fact of the matter is that Jewish thinking on sexual ethics, as with most other things, is conten- tious, multivocal, and often contradictory. However, there are actually two levels on which this question operates. The first level is what the multiplicity of classical Jewish traditions have offered directly on matters of sexual conduct—what “Judaism says about sex.” The second level is the way modern and con- temporary thinkers have presented classical sources on sex and sexuality—what “Jewish thinkers say Judaism says about sex.” In the past seventy years or so, as the academic study of Jewish ethics has gained an institutional foothold and as rab- bis and Jewish public intellectuals have had to grapple with changes in public sexual mores and with the increasing reach of popular media, both of these levels of the question have, at least in Jewish thought in the U.S. and Canada, exhibited some clear trends. Here, I offer an analysis and a critique of these trends, especially in academic Jewish sexual ethics as it cur- rently stands, and suggest some directions for its future growth. I organize literature in modern and contemporary Jewish sexual ethics according to a typology of “cautious” versus “ex- pansive,” a typology which does not fall neatly along denomi- 14 Is Judaism ‘Sex Positive?’ national lines. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES English Department Hasidic Judaism in American Literature by Eva van Loenen Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF YOUR HUMANITIES English Department Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy HASIDIC JUDAISM IN AMERICAN LITERATURE Eva Maria van Loenen This thesis brings together literary texts that portray Hasidic Judaism in Jewish-American literature, predominantly of the 20th and 21st centuries. Although other scholars may have studied Rabbi Nachman, I.B. Singer, Chaim Potok and Pearl Abraham individually, no one has combined their works and examined the depiction of Hasidism through the codes and conventions of different literary genres. Additionally, my research on Judy Brown and Frieda Vizel raises urgent questions about the gendered foundations of Hasidism that are largely elided in the earlier texts.