University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

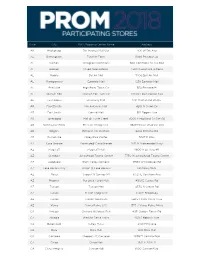

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

Dfw Toll Road Guide

DFW TOLL ROAD GUIDE OPEN TO TRAFFIC PROPOSED/IN PLANNING UNDER CONSTRUCTION Independence Title LEARN MORE IndependenceTitle.com OPEN TO TRAFFIC PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION To order a motorcycle tag, call 1-888-468-9824. A refundable deposit TxTag is required. With an electronic TxTag sticker on Bumper Tags: Bumper tags are required for vehicles with certain your windshield, you can pay tolls windshields. Because bumper tags can be reused, a refundable without stopping at a toll booth or deposit is required. If you have questions, call 1-888-468-9824. digging for change. As you enter or exit the toll road, a device above the How do I get a TxTag? road reads a signal from the microchip Online (txtag.org) inside your tag and automatically deducts the toll from Filling out an online application form takes only a few minutes. Your TxTag will be mailed to you within 3-4 business days already activated your pre-paid TxTag account. and ready for immediate installation. How does TxTag Work? By Phone TxTag makes paying tolls simple and fast. Call the TxTag Customer Service Center Monday-Friday, from 8:00 a.m. There's no stopping or slowing down to pay, no waiting in line at a toll to 7:00 p.m., toll-free at 1-888-468-9824. A representative will assist you booth and no searching for change on toll roads across Texas. The TxTag with the short application process. sticker goes on the inside of your windshield behind your rearview mirror. An electronic reader above the toll roads sends a signal to the By Mail microchip inside the sticker, and tolls are automatically deducted from You may also download and print the application for a TxTag. -

General Growth Properties, Inc. Case Number: 09-11977

General Growth Properties, Inc. Attachment 4a Case Number: 09-11977 4a. Suits and Administrative Proceedings - Debtor as Plaintiff Case Name Case Number Court Name and Location GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES, INC. V. CHICAGO DEPARTMENT OF REVENUECASE NO. 08 TX 0182 DEPARTMENT OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS, TAX SECTION OF THE CITY OF CHICAGO If a Debtor entity does not appear as a named party in a particular line item on this Statement of Financial Affairs it is because that Debtor is named under the full case name rather than the abbreviated case caption set forth on this Schedule. If multiple Debtors are parties in a given proceeding, that proceeding will be listed on Attachment 4(a) of the Statement for each Debtor named. Attachment 4(a)(i) lists those suits where the Debtor is a Plaintiff; Attachment 4(a)(ii) lists those suits where the Debtor is a Defendant. LID: 1 1 General Growth Properties, Inc. Attachment 4a(ii) Case Number: 09-11977 4a(ii). Suits and Administrative Proceedings - Debtor as Defendant Case Name Case Number Court Name and Location ACCESS FOR THE DISABLED, INC., A FLORIDA NOT FOR PROFIT CORPORATION, AND DENISE 6:08-CV-1645-ORL-31- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF PAYNE, INDIVIDUALLY, V. GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES, A FOREIGN TRUST DAB FLORIDA; FLORIDA ACCESS FOR THE DISABLED, INC., A FLORIDA NOT-FOR-PROFIT CORPORATION, AND DENISE CASE NO. 1:09-CV-43 U.S. DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PAYNE, INDIVIDUALLY V. GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES, INC., A DELAWARE CORPORATION MICHIGAN, SOUTHERN DIVISION; MICHIGAN AILEEN BETANCOURT-ESPADA V. -

Official Rules

OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE AN ENTRANT’S CHANCES OF WINNING. OPEN TO LEGAL RESIDENTS OF THE UNITED STATES AND THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA (EXCLUDING FLORIDA, NEW YORK AND RHODE ISLAND) WHO ARE AT LEAST 18 YEARS OF AGE AT THE TIME OF ENTRY. VOID IN FLORIDA, NEW YORK, RHODE ISLAND AND WHERE PROHIBITED OR RESTRICTED BY LAW. To Enter: NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. PURCHASE WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. To be eligible, entrant (“Entrant”) must provide the Administrator (as defined herein) of this promotion (the “Promotion”), Pro Silver Star, Ltd. (the “Administrator”) and J.C. Penney Corporation Inc. (the “Sponsor”), with its full name, email address, phone number, zip code and date of birth. Limit one (1) entry per person. Administrator will not be responsible for entries lost, delayed, incomplete or misdirected. Entries will become the sole property of Administrator and by entering, Entrant expressly consents to adding his/her name to receive future promotional offers, and using Entrant’s name for advertising, publicity or any other purposes whatsoever, as determined by Administrator in its sole discretion, without compensation and with or without attribution to Entrant, as Sponsor and/or Administrator in their sole discretion, without compensation and with Method of Entry: A. Purchase and Online Entry: Entry codes are available with the purchase of one (1) limited edition fleece bearing The Salvation Army and Dallas Cowboys trademarks (the “Fleece”) at select JCPenney stores in Texas as listed in the Appendix of these Official Rules (each a “Participating Store” and collectively the “Participating Stores”), while supplies last. -

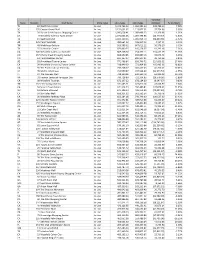

State Storeno Mall Name Store Type 2015 Sales 2014 Sales Variance

Variance State StoreNo Mall Name Store Type 2015 Sales 2014 Sales Inc/(Dec) % Inc/(Dec) TX 83 NorthPark Center In-Line 1,472,766.00 1,363,984.00 108,782.00 7.98% SC 135 Coastal Grand Mall In-Line 1,151,631.67 1,113,877.31 37,754.36 3.39% TX 20 Barton Creek Square Shopping Center In-Line 1,096,658.41 1,083,499.33 13,159.08 1.21% CA 8 Westfield Valencia Town Center In-Line 1,071,022.26 1,087,795.83 (16,773.57) -1.54% TX 19 Baybrook Mall In-Line 1,025,120.43 1,055,953.79 (30,833.36) -2.92% AZ 125 Park Place Mall In-Line 950,664.23 946,527.12 4,137.11 0.44% TN 48 Wolfchase Galleria In-Line 923,588.32 867,012.22 56,576.10 6.53% TX 55 Stonebriar Centre In-Line 876,800.55 815,558.37 61,242.18 7.51% CA 126 Westfield Galleria at Roseville In-Line 869,168.30 754,757.11 114,411.19 15.16% CO 167 Cherry Creek Shopping Center In-Line 868,959.85 835,887.13 33,072.72 3.96% CO 61 Park Meadows Center In-Line 831,157.07 800,397.91 30,759.16 3.84% AZ 28 Arrowhead Towne Center In-Line 771,406.64 656,746.72 114,659.92 17.46% CA 39 Westfield University Towne Center In-Line 738,949.33 573,464.00 165,485.33 28.86% CA 35 The Promenade at Temecula In-Line 733,268.27 666,557.65 66,710.62 10.01% KY 78 Mall St. -

2019 Dallas Cowboys Training Camp Promo

Training Camp Store Allocations Store Number Name Address 2685 The Parks Mall 3851 S Cooper St 2795 Stonebriar Mall 2607 Preston Rd 2434 Coronado Center 6600 Menaul Blvd NE Ste 3000 2939 North Star Mall 7400 San Pedro Ave 226 La Plaza 2200 S 10th St 2904 Southpark Meadows S/C 9500 S IH-35 Ste H 631 Ingram Park Mall 6301 NW Loop 410 702 Cielo Vista Mall 8401 Gateway Blvd W 1330 La Palmera Mall 5488 S Padre Island Dr Ste 4000 179 Timber Creek Crossing 6051 Skillman St 2946 Plaza at Rockwall 1015 E I 30 2877 The Rim Shopping Center 17710 La Cantera Pkwy 2338 Town East Mall 6000 Town East Mall 2055 Collin Creek Mall 821 N Central Expwy 1046 Golden Triangle Mall 2201 S Interstate 35 E Ste D 2410 Vista Ridge Mall 2401 S Stemmons Fwy Ste 4000 2884 Tech Ridge Center 12351 N IH-35 2826 Cedar Hill Village 333 N Hwy 67 2960 El Mercado Plaza 1950 Joe Battle Blvd 2969 Sherman Town Center 610 Graham Dr 2934 University Oaks Shopping Center 151 University Oaks 993 South Park Mall 2418 SW Military Dr 2982 Village at Fairview 301 Stacy Rd 2921 Robertsons Creek 5751 Long Prairie Rd 2105 Crossroads Mall 6834 Wesley St Ste C 1943 North East Mall 1101 Melbourne Dr Ste 5000 1419 Ridgmar Mall 1900 Green Oaks Rd 2093 Mesilla Valley Mall 700 Telshor Blvd Ste 2000 2021 Richland Mall 6001 W Waco Dr 579 Music City Mall 4101 E 42nd St 485 Mall of Abilene 4310 Buffalo Gap Rd 2682 Penn Square Mall 1901 NW Expwy Ste 1200 2833 Rolling Oaks Mall 6909 N Loop 1604 E 2806 Sunrise Mall 2370 N Expwy Ste 2000 712 Sikes Senter Mall 3111 Midwestern Pkwy 996 Broadway Square Mall 4401 S Broadway 450 Rio West Mall 1300 W Maloney Ave Ste A 1749 Central Mall 2400 Richmond Rd Ste 61 2905 Alliance Town Center 3001 Texas Sage Trl 658 Mall De Norte S/C 5300 San Dario 1989 Sunset Mall 6000 Sunset Mall 259 Colonial/Temple Mall 3111 S 31st St Ste 3301 1101 Valley Crossing Shopping Center 715 E Expressway 83 2036 Midland Park Mall 4511 N Midkiff Rd 304 Longview Mall 3550 McCann Rd 2110 Killeen Mall 2100 S W.S. -

Board Meeting |AGENDA 2700 W

Plano Independent School District Board Meeting |AGENDA 2700 W. 15th Street Plano, Texas 75075 May 19, 2020 Vision Mission Strategic Plan Pillars Committed to Excellence Our Plano ISD learning community will educate, Pillar 1: Learning and Teaching Dedicated to Caring inspire and empower every student to activate Pillar 2: Life Ready Powered by Learning their unique potential in a dynamic world. Pillar 3: Talent Acquisition, Support & Growth Plano ISD Proud. Pillar 4: Culture of Community Pillar 5: Strategic Resource Management The 2019 – 2023 Strategic Plan was approved by the Board of Trustees on April 9, 2019. 1. CALL TO ORDER: 6:00 P.M. Due to health and safety concerns related to the COVID-19 coronavirus, the Board Meeting will be conducted by videoconference to maintain the public health. Further, pursuant to Governor Abbott’s temporary suspension of the requirement related to the location of a quorum issued on March 16, 2020, the quorum will not be present at any one location, rather, the quorum will be participating by videoconference. The Board Meeting may be viewed via live stream at https://www.pisd.edu/pisdlive. An electronic copy of agenda materials is available at https://www.pisd.edu/Page/19763. Additionally, a recording of the meeting will be posted online as soon as possible after the conclusion of the meeting. 2. CLOSED SESSION: 6:00 P.M. In accordance with BE(LOCAL), notice of all meetings shall provide for the possibility of a closed meeting during an open meeting, in accordance with law. Closed Session will be held for the purposes authorized by the Texas Open Meetings Act, Texas Government Code Section 551.001 et seq. -

Cracking Back: the Effectiveness of Partisan Redistricting in the Texas House of Representatives

Cracking Back: The Effectiveness of Partisan Redistricting in the Texas House of Representatives Brian K. Arbour and Seth C. McKee We assess the partisan consequences of alternative redistricting plans in 2001 for the Texas House of Representatives. In the paper, we combine a methodological tool (the JudgeIt program) that allows us to examine both enacted and proposed redistricting maps with data from not only the districts used in the 2002 and 2004 Texas House elections, but also from districts that existed only in proposed plans. We find that each redistricting plan benefited their sponsor’s party. In fact, a plan supported and advocated by Democratic Speaker Pete Laney is projected to have kept a Democratic majority in the Texas House after the 2002 elections. Our data also demonstrate that rules matter in redistricting, especially in the context of substantial party system change shown by the growth of the Republican Party in Texas. In 2003, the redistricting battle in Texas played out in dramatic fashion, as Democrats in the Texas House and Texas Senate both left the state at different times in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to stop the majority in the Legislature from implementing a congressional redistricting plan that greatly favored Republicans. In this paper, we show that the drama provided by the escapes to Ardmore, Oklahoma and Albuquerque, New Mexico are the result of a previous redistricting—the 2001 redrawing of lines for the Texas House of Representatives. Those new lines allowed Republicans to take the majority in that body in the 2002 elections and complete the first sweep of Texas government by Republicans since Reconstruction. -

Plano City Council Will Convene Into Executive

PLANO CITY COUNCIL WILL CONVENE INTO EXECUTIVE SESSION AT 5:00 P.M. ON OCTOBER 13, 2008, FOLLOWED BY PRELIMINARY OPEN MEETING IN THE PLANO MUNICIPAL BUILDING, 1520 K AVENUE, IN COMPLIANCE WITH VERNON'S TEXAS CODES ANNOTATED, GOVERNMENT CODE CHAPTER 551 (OPEN MEETINGS ACT), AS FOLLOWS: Mission Statement: The mission of the City of Plano is to provide outstanding services and facilities, through cooperative efforts with our citizens, that contribute to the quality of life in our community. EXECUTIVE SESSION I. Legal Advice Wetherbee 5 min. A. Respond to questions and receive legal advice on agenda items B. Regarding City participation in a W. Christopher Schaeper 60 min. long term power supply contract for its City facilities and services II. Personnel Council 15 min. A. Evaluation of Council Appointees B. Re-Appointments/Appointm ents to Boards and Commissions Heritage Commission Planning and Zoning Commission Plano Housing Authority Retirement Security Plan Committee PRELIMINARY OPEN MEETING I. Consideration and action resulting from Council 5 min. Executive Session discussion: Personnel: A. Re-appointments/Appointm ents to Boards and Commissions Heritage Commission Planning and Zoning Commission Plano Housing Authority Retirement Security Plan Committee II. Personnel Council 15 min. A. Re-Appointments/Appointments to Boards and Commissions Parks and Recreation Planning Board Library Advisory Board Community Relations Commission Cultural Affairs Commission Animal Shelter Advisory Committee Public Arts Committee Self Sufficiency Committee Senior Citizens Advisory Board TIF Zone No.1 Board III. Discussion re Chisholm Trail South Master Plan Zimmerman 10 min. IV. Discussion re Valet Parking Turner 10 min. V. Council items for discussion/action on future agendas Council 5 min. -

John Ben Shepperd, Jr. Memorial Library Catalog

John Ben Shepperd, Jr. Memorial Library Catalog Author Other Authors Title Call Letter Call number Volume Closed shelf Notes Donated By In Memory Of (unkown) (unknown) history of the presidents for children E 176.1 .Un4 Closed shelf 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) Ruth Goree and Jane Brown 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) Anonymous 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) Bobbie Meadows Beulah Hodges 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1977 Inaugural Committee A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America F 200 .A17 (1977) 1981 Presidential Inaugural Committee (U.S.) A Great New Beginning: the 1981 Inaugural Story E 877.2 .G73 A Citizen of Western New York Bancroft, George Memoirs of General Andrew Jackson, Seventh President of the United States E 382 .M53 Closed shelf John Ben Shepperd A.P.F., Inc. A Catalogue of Frames, Fifteenth Century to Present N 8550 .A2 (1973) A.P.F. Inc. Aaron, Ira E. Carter, Sylvia Take a Bow PZ 8.9 .A135 Abbott, David W. Political Parties: Leadership, Organization, Linkage JK 2265 .A6 Abbott, John S.C. Conwell, Russell H. Lives of the Presidents of the United States of America E 176.1 .A249 Closed shelf Ector County Library Abbott, John S.C. -

Request for Bids (RFB) for Sam Rayburn Tollway Segment

Request for Bids (RFB) for Sam Rayburn Tollway Segment 3 Frontage Roads (SH 121) Restriping Solicitation Number: 05261-SRT-00-CN-PD Date Issued December 18, 2020 Date Revised Pre-Bid Conference January 12, 2021 at 3:00 p.m. CT Microsoft Teams Virtual Meeting Details: Virtual Pre-Bid Conference Request meeting presentation from: Join Microsoft Teams Meeting Reginald Valentine, Sr. Procurement Specialist +1 469-214-9499 United States, Dallas (Toll) [email protected] Conference ID: 108 781 198# Bid Question Deadline January 14, 2021 at 5:00 p.m. CT Submit Questions via www.nttamarketplace.org January 21, 2021 at 11:00 a.m. CT NTTA Bid Due Date 5900 West Plano Parkway, Suite 100, Submit Bids via www.nttamarketplace.org Customer Service Center, Plano, Texas 75093 January 21, 2021 at 3:00 p.m. CT Bid Opening Date Virtual Bid Opening Microsoft Teams Virtual Meeting Details: Join Microsoft Teams Meeting +1 469-214-9499 United States, Dallas (Toll) Conference ID: 313 699 906# Solicitation Contact Person Reginald Valentine, Sr. Procurement Specialist [email protected] Contract Term 5 Months Project Description: Removal and installation of new thermoplastic pavement markings along the SH-121 Frontage Road and all intersections from south of Dallas North Tollway to north of Medical Center Drive. Work includes long lines, skips, graphics and raised pavement markers as well as the installation of delineators on the MBGF and concrete rail along the SH-121 Frontage Roads. NOTE: To be considered for this procurement, each Bidder MUST include with their Bid Sheet, and all REQUIRED documents. Bidders are encouraged to upload their bids to NTTA’s Marketplace (https://www.nttamarketplace.org), no later than the date and time identified above as the “Bid Due Date”. -

1. Follow Dallas North Tollway N 2. Take the Exit Towards Warren Pkwy/Gaylord Pkwy 3

DIRECTIONS FROM DOWNTOWN DALLAS: 1. Follow Dallas North Tollway N 2. Take the exit towards Warren Pkwy/Gaylord Pkwy 3. Use the 2nd from the left lane to turn LEFT onto Warren Pkwy 4. Turn Right onto Gaylord Pkwy 5. Turn left to enter the Omni Frisco Hotel. DIRECTIONS FROM DFW: 1. Take TX-121 N and Sam Rayburn Tollway to Frisco and follow signs for Dallas North Tollway N. 2. Using the 2nd from the right lane to take the exit. 3. Keep left at the fork, and merge onto Dallas North Tollway N. 4. Take the exit for Lebanon Rd, make a U-turn to cross under the Dallas North Tollway and continue on Dallas Pkwy S frontage road. 5. Turn right onto Cowboys Way and right onto Gaylord Pkwy 6. Turn left to enter the Omni Frisco Hotel. DIRECTIONS FROM OKLAHOMA: 1. Take I-35E S Towards Denton to TX-121N and Sam Rayburn Tollway to Frisco 2. Using the 2nd from the right lane to take the exit 3. Keep left at the fork, and merge onto Dallas North Tollway N. 4. Take the exit for Lebanon Rd, make a U-turn to cross under the Dallas North Tollway and continue on Dallas Pkwy S frontage road 5. Turn right onto Cowboys Way and right onto Gaylord Pkwy 6. Turn left to enter the Omni Frisco Hotel. DIRECTIONS FROM EAST TEXAS: 1. Take I-30 W towards Dallas 2. Take exit 96 for TX-302 Spur W in Greenville. 3. Keep right to continue on Lee St.