ANNUAL REPORT 1 APRIL 2018 to 31 MARCH 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

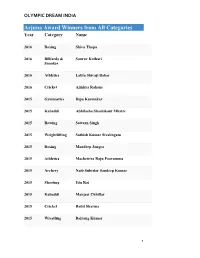

Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name

OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name 2016 Boxing Shiva Thapa 2016 Billiards & Sourav Kothari Snooker 2016 Athletics Lalita Shivaji Babar 2016 Cricket Ajinkya Rahane 2015 Gymnastics Dipa Karmakar 2015 Kabaddi Abhilasha Shashikant Mhatre 2015 Rowing Sawarn Singh 2015 Weightlifting Sathish Kumar Sivalingam 2015 Boxing Mandeep Jangra 2015 Athletics Machettira Raju Poovamma 2015 Archery Naib Subedar Sandeep Kumar 2015 Shooting Jitu Rai 2015 Kabaddi Manjeet Chhillar 2015 Cricket Rohit Sharma 2015 Wrestling Bajrang Kumar 1 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2015 Wrestling Babita Kumari 2015 Wushu Yumnam Sanathoi Devi 2015 Swimming Sharath M. Gayakwad (Paralympic Swimming) 2015 RollerSkating Anup Kumar Yama 2015 Badminton Kidambi Srikanth Nammalwar 2015 Hockey Parattu Raveendran Sreejesh 2014 Weightlifting Renubala Chanu 2014 Archery Abhishek Verma 2014 Athletics Tintu Luka 2014 Cricket Ravichandran Ashwin 2014 Kabaddi Mamta Pujari 2014 Shooting Heena Sidhu 2014 Rowing Saji Thomas 2014 Wrestling Sunil Kumar Rana 2014 Volleyball Tom Joseph 2014 Squash Anaka Alankamony 2014 Basketball Geetu Anna Jose 2 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2014 Badminton Valiyaveetil Diju 2013 Hockey Saba Anjum 2013 Golf Gaganjeet Bhullar 2013 Athletics Ranjith Maheshwari (Athlete) 2013 Cricket Virat Kohli 2013 Archery Chekrovolu Swuro 2013 Badminton Pusarla Venkata Sindhu 2013 Billiards & Rupesh Shah Snooker 2013 Boxing Kavita Chahal 2013 Chess Abhijeet Gupta 2013 Shooting Rajkumari Rathore 2013 Squash Joshna Chinappa 2013 Wrestling Neha Rathi 2013 Wrestling Dharmender Dalal 2013 Athletics Amit Kumar Saroha 2012 Wrestling Narsingh Yadav 2012 Cricket Yuvraj Singh 3 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2012 Swimming Sandeep Sejwal 2012 Billiards & Aditya S. Mehta Snooker 2012 Judo Yashpal Solanki 2012 Boxing Vikas Krishan 2012 Badminton Ashwini Ponnappa 2012 Polo Samir Suhag 2012 Badminton Parupalli Kashyap 2012 Hockey Sardar Singh 2012 Kabaddi Anup Kumar 2012 Wrestling Rajinder Kumar 2012 Wrestling Geeta Phogat 2012 Wushu M. -

Progressive Role of Women in Indian Economy

© 2019 JETIR May 2019, Volume 6, Issue 5 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) PROGRESSIVE ROLE OF WOMEN IN INDIAN ECONOMY D.MAHESWARI , ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, ADITYA ENGINEERING COLLEGE,EAST GODAVARI(Dt) ABSTRACT Present paper aims to draw the attention and emphasize the important role of women in economic development of India. Development alone can play a major role in driving down inequality between men and women; in the other direction, empowering women may promote development. Development policies and programs tend not to view women as integral to the economic development process. This is reflected in the higher investments in women's reproductive rather than their productive roles, mainly in population programs. Yet women throughout the developing world engage in economically productive work and earn incomes. They work primarily in agriculture and in the informal sector and increasingly, in formal wage employment. Their earnings, however, are generally low. Since the 1950s, development agencies have responded to the need for poor women to earn incomes by making relatively small investments in income-generating projects. Often such projects fail because they are motivated by welfare and not development concerns, offering women temporary and part-time employment in traditionally feminine skills such as knitting and sewing that have limited markets. By contrast, over the past twenty years, some non-governmental organizations, such as the Self-help groups in India, have been effective in improving women's economic status by extending loan facilities that are fundamental to the process of economic development. What are the current constraints on realising the full potential of women in the process of economic development intervention necessary to unblock these constraints? It is focussed on women and on economic development, rather than on the wider issue of discrimination between genders. -

List of Qualified Candidates for B.Sc. (Hons.) Exam 2014 ALL INDIA REG

List of Qualified Candidates for B.Sc. (Hons.) Exam 2014 ALL INDIA REG. NO NAME FATHER'S NAME MOTHER'S NAME ROLL NO. CATEGORY RANK 1731009420 RAJSHREE NARENDER GUPTA DEEPA GUPTA 4504987 UR 1 1731000582 ANU NARWAL SUBHASH NARWAL RAJPATI NARWAL 4504986 UR 2 1731008448 SRISHTI DABAS VIJENDER SINGH SANTOSH 4505428 OBC(NCL) 3 1731006200 SHAGUN THAKUR VINOD THAKUR KUSUM THAKUR 4502979 UR 4 1731004743 SANGEETA VISHNOI JIWANRAM SINWARI DEVI 4503622 UR 5 1731006235 MONIKA NEGI GAJPAL SINGH NEGI SAROJ NEGI 4504606 UR 6 1731001406 ANISHA SUSAN MATHEW MATHEW P JACOB SHEEBA MATHEW 4503381 UR 7 1731003594 VANDANA YADAV DHARMVEERYADAV SUSHIL YADAV 4503321 OBC(NCL) 8 1731006390 SREELAKSHMI S SATHISHKUMAR G BINDU 4504260 UR 9 1731001390 GLORIYA RACHEL THOMAS THOMAS CHERIAN BLESSY K THOMAS 4505355 UR 10 1731004633 RASHMI KUMARI NEELAMBAR PRASAD YADAV NEELAM YADAV 4502294 OBC(NCL) 11 1731008898 RUBY KUMARI SADANAND MANDAL REKHA DEVI 4505252 OBC(NCL) 12 1731004472 ESHA SAINI MUKHTIAR SINGH NISHA SINGH 4505144 UR 13 1731006138 MADHU KAJAL PARDEEP KAJAL MUNNI KAJAL 4503766 OBC(NCL) 14 1731002666 VARSHA SEHRAWAT YOGENDER KUMAR BABITA 4503337 UR 15 1731006526 MONIKA RAJBIR SARLA 4502782 UR 16 1731000883 LINTA THOMAS THOMAS MATHEW ELIZABETH THOMAS 4502693 UR 17 1731000103 LUXMI SHARMA RADHEY SHYAM SHARMA DARSHNA DEVI 4505001 UR 18 1731009360 KANIKA UPRETI HANSA DUTT HANSI UPRETI 4504097 UR 19 1731008875 KOMAL BAGHAIL AMAR SINGH SUMAN 4504146 OBC(NCL) 20 1731007978 DIPALI RAWAL CHANDU LAL SHOBHA 4503522 UR 21 1731004570 POOJA UMESH CHANDRA BAGESHWARI 4503001 UR -

Nari Shakti E Book

NARI SHAKTI PURASKAR, 2016 MINISTRY OF WOMEN AND CHILD DEVELOPMENT GOVERNMENT OF INDIA u, lekt dh vksj Towards a new dawn The Government of India has decided to confer “Nari Shakti Puruskar” on eminent women and institutions rendering distinguished service to the cause of NARI SHAKTI PURASKAR women especially belonging to the vulnerable and marginalized sections of the society. These include institutional and individual awards for making outstanding contributions to women’s endeavor/community work/making a difference/women rom time immemorial, women in India have excelled in diverse fields. The empowerment. Fcontributions made by women saints, philosophers like Meera Bai, Gargi and Maitreyi, theologists like Anupama and Lopamudra, poetesses like Reva and Mahadevi, Nari Shakti Puruskar would carry a cash award of Rs. 1 lakh and a certificate for scientists like Leelavati in ancient and medival India are recorded in golden letters in individuals and Institutions. the annals of Indian history. This year Ministry of Women & Child Development sought nominations from the In modern India, and more particularly since Independence, more and more State Governments, Union Territory Administrations, concerned Central Ministries, women have come forward to shoulder responsibilities with men in various walks of Non-Governmental Organizations, Universities, Institutions, Private and Public life. Sarojini Naidu and Kasturba Gandhi were at the forefront of our freedom struggle. sector undertakings (PSUs) working for empowerment of women for consideration Indira Gandhi, the longest serving woman head of Government in the world. Vijaya of Selection Committee under the Chairpersonship of the Minister, Ministry of Laxmi Pandit became the first woman President of the General Assembly of the United Women and Child Development. -

Nari Shakti Puraskar" Guidelines

DEPARTMENT OF WOMEN & CHILD DEVELOPMENT GOVT. OF NCT OF DELHI (WOMEN EMPOWERMENT CELL) IIND FLOOR, ISBT BUILDING, KASHMERE GATE, DELHI-110006 email id- [email protected] F. No. 60(456)/DWCD/WEC/Misc./2016 Date: )A1 To, The Data Processing Analyst DWCD, GNCTD 2nd floor, Kashmere Gate Delhi-110006 Subject: Regarding the uploading of "Nari Shakti Puraskar" Guidelines Sir, In reference to the subject captioned above, you are requested to upload the guidelines of "Nari Shakti Puraskar" on the website of Department of Women and Child Development, Govt. of NCT of Delhi at the earliest. For more details about the "Nari Shakti Puraskar" the aspirants may visit the website http ://www. wcd.nic. in. Encl: Guidelines of Nari Shakti Puraskar Assistant Director (WEC) ftvg tivcm kr4 41(4 fkWiii uflIrdff,T Iec4l — 110 001 RAM MOHAN MISHRA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Secretary MINISTRY OF WOMEN & CHILD DEVELOPMENT SHASTRI BHAWAN, NEW DELHI-110 001 Web:311e : http://www.wed-nlc.In D.O. No. 21/1/2018- D/IC(e-58090) Dated: 22nd January, 2021 Dear Chief Secretary, As you would be aware, 8th March is celebrated all over world as International Women's Day. Being the nodal Ministry for welfare of women, Ministry of Women and Child Development has been celebrating International Women's Day every year by felicitating eminent individuals, organizations, groups, NGOs and institutions with National awards called 'Nari Shakti Puraskar' in recognition of their exceptional contribution towards women's empowerment. Accordingly, this year also the Nari Shakti Puraskar for the year 2020 will be awarded on International Women's Day i.e. -

MARCH 3RD WEEK CURRENT AFFAIRS TAMILNADU EDUCATION Planys Technologies an IIT Madras Incubated Start Up

MARCH 3RD WEEK CURRENT AFFAIRS TAMILNADU EDUCATION Planys Technologies An IIT madras incubated start up – develops ‘Mikros’, an underwater Remotely operated vehicle (ROV) for Oil & Gas industries. Solar-powered desalination plant IIT, Madras sets up country’s first solar-powered desalination plant near Vivekananda Memorial at Kanyakumari. NATIONAL India was ranked 16th in the world in terms of highest number of impacted species in biodiversity-rich zones (also known as hotspots). Malaysia ranks first among countries with highest number of impacted species (on an average 125 species). INTERNATIONAL The African Development Bank (AfDB) would provide 5 trillion shillings ($25 billion) over the next 5 years to help in the global fight against climate change. The fourth session of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA-4) took place in Nairobi, Kenya, as agreed during UNEA-3 in December 2017. Under the overall theme, ‘Innovative Solutions for Environmental Challenges and Sustainable Consumption and Production’. Kazakhstan renames its capital Astana as Nursultan after ex-president. ECONOMY World Bank to provide a $250-million loan for the National Rural Economic Transformation Project (NRETP). SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY A man-portable anti-tank guided missile (MPATGM) was successfully test- fired in Rajasthan and developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO). Astronomers have discovered 83 quasars powered by supermassive black holes 13 billion light-years away from the Earth, from a time. APPOINTMENTS NAME APPOINTED BY Gauri Sawant first transgender election ambassador by The Election Commission of India. Pramod Sawant (BJP MLA and Former 13th Chief Minister of Goa succeeding Speaker of Goa legislative assembly) Manohar Parrikar, who died due to Cancer. -

Jun,2013.Pdf

Peshi Report in Period From 01-08-2013 To 30-08-2013 S.No Sl.No Reg No First Party 2nd Party Type of Deed Address Value Stamp Paid Book No. Basai Darapur , House No. B- 268-267 Basai darapur ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 200, Area2 0, Area3 0 1 15541 Balwinder Kaur Sachin Nayyar SALE , SALE WITHIN MC AREA Basai Darapur 3950000 237000 1 Basai Darapur , House No. WZ- 56 ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 216, Area2 0, 2 15978 BHAGIRATI TYAGI ABDUL WASI SALE , SALE WITHIN MC AREA Area3 0 Basai Darapur 2100000 126000 1 Basai Darapur , House No. WZ- 56 ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 142, Area2 0, 3 15984 BHAGIRATI TYAGI PARVEEN AKHTAR SALE , SALE WITHIN MC AREA Area3 0 Basai Darapur 2910000 116400 1 Basai Darapur , House No. WZ- 56 SF BASAI DARAPUR ND ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 SMT BHAGIRATI 0, Area2 0, Area3 0 Basai 4 15977 TYAGI SHRI ABDUL WAHAB SALE , SALE WITHIN MC AREA Darapur 2910000 174600 1 Basai Darapur , House No. WZ- 56 GF ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra 722/2, Area1 216, Area2 0, Area3 0 Basai 5 15982 Smt Bhagirati tyagi Sh Abdul Samad SALE , SALE WITHIN MC AREA Darapur 2910000 174600 1 Basai Darapur , House No. B- 268-267 Basai darapur ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 200, Area2 0, Area3 0 6 15539 Balwinder Kaur Sakshi SALE , SALE WITHIN MC AREA Basai Darapur 3950000 158000 1 East Patel Nagar , House No. 7/28 shop no-3 GF ,Road No. , Mustail No. -

Current Affairs of March 2020

www.leadthecompetition.in CURRENT AFFAIRS FOR THE MONTH OF MARCH 2020 Awards The Indian-origin American author who has been chosen to be awarded the PEN/Hemingway Award 2020 for her first novel A Prayer for Travelers – Ruchika Tomar Persons The renowned Indian painter, sculptor, muralist and writer, (Padma Vibhushan awardee and brother of former PM IK Gujral) who passed away on 26 March 2020 – Satish Gujral The former Indian footballer, Padmashree and Arjuna awardee, who passed away on 20 March 2020 – PK Banerjee The high level technical committee of 21 Public Health Experts constituted by Govt of India for preventing and controlling COVID-19 in the country is headed by – Dr V K Paul The former Chief Justice of India who has been nominated to the Rajya Sabha by the Indian President Shri Ram Nath Kovind – Shri Ranjan Gogoi The former chief financial officer and deputy managing director of State Bank of India who has been appointed the MD and CEO of Yes Bank – Prashant Kumar The team which has won the 2019-20 Ranji Trophy title defeating Bengal in the finals at Rajkot – Saurashtra The former Secretary General of the United Nations Organisation who passed away on 04 March 2020 – Javier Perez de Cuellar The new Finance Secretary of India replacing Shri Rajiv Kumar – Ajay Bhushan Pandey The new Prime Minister of Malaysia appointed after the resignation of Mr. Mahathir Mohammed – Muhyiddin Yassin Places The venue of Wings-2020 the biennial civil aviation and aerospace event organised by Ministry of Civil Aviation, Airports Authority of India -

Issue 04 | 2019

SHOOTING FOR THE STARS Four inspirational tales THE MASKETEERS OF MAJULI Maskmaking at India’s largest riverine island THE GREEN RESPONSIBILITY Trekking and sustainability Volume 33 | Issue 04 | 2019 HANDS OF FRIENDSHIP PM Narendra Modi’s successful visit to the United States of America POTPOURRI Potpourri Events of the season OCTOBER, 2019 TO 23 FEBRUARY, 2020 RANN UTSAV This annual festival offers visitors a true blue experience of the unique culture and traditional lifestyle of the Great Rann of Kutch. The event also showcases the handicrafts 28 and artistic heritage of the region through carefully- curated events and fairs. 8NOVEMBER, 2019 WHERE: Great Rann of Kutch, Gujarat WANGALA FESTIVAL 8-12NOVEMBER, 2019 This festival, also known as the 100-drum PUSHKAR CAMEL FAIR festival, is celebrated by the Garo tribes of the hills of Meghalaya. Villagers from A highly recommended travel experience, the Pushkar the area come together to celebrate this festival, which marks a bountiful harvest. camel fair is a vibrant livestock and cultural festival held Musical performances and dances mark on the banks of the sacred Pushkar lake in Rajasthan. With the festival, where the focus is on the numerous friendly competitions and cultural evenings, the traditional drums of the region. festival is quite a lively affair. WHERE: Garo Hills, Meghalaya WHERE: Pushkar, Rajasthan INDIA PERSPECTIVES | 2 | DECEMBER, 2019 TO 28 NOVEMBER, 2019 1-10 20 HORNBILL FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL One of the biggest annual events in the Northeast, the Started in 1952, the International Film Hornbill Festival celebrates the vibrant cultural mosaic of Festival of India (IFFI) has grown to become Nagaland. -

June 11, 2021

www.tiryimyim.in Regd. No. RNI. NAGAAO/ 2004 / 13113. Postal-NE/RN-717. e-mail : [email protected] TAPAK 8 Yangia anidakangma : Tir Yimyim tiryimyim@aolima tir yimyim TAPAK 10 Myanmar nung Aung San Suu Kyi Asian Games nung gold medal takok anema ken o tasen benoker angusang Dingko Singh süogo VOL. XVIII NO. 237 (ADOK 237) DIMAPUR ROGONÜ (FRIDAY) AAMI (JUNE) 11, 2021 ` 5.00 Nagaland COVID-19: Tasen puteter CM Neiphiu Rio-i Nagaland COVID Information App amenoktsü case jenjang, ICU yipden kwi dang taneptsü angur timba tazüng lir, Oxygen aser Ventilator Kohima, Aami/June 10 inoker lir aser nisung 11 kwi lir, sorkari agütsüba tetuyuba (TYO): Nagaland nung anogo ventilator nung lir, aser nisung aser osang balala, jongdak pongububa atonga nisung tasen 3,591 temang nung iba tashidak mapang tongteprateptsü atema dak COVID-19 tashidak putetba agi timtem agütsüba mali, ta pai contact, COVID-19 tashidak dang iba tashidak nungi taneptsü ashi. tendangba tesemtem indang angur timba liasü. Brehostibarnü Brehostibarnü Dimapur aser osang, COVID-19 vaccine agiba state nung nisung 117 Phek nung nisung ana-na, tesem osang densema lir aser coronavirus nungi taneptsü angu Kohima aser Mokokchung nung Hospital help desk den mobile app aser nisung 113 dak iba tashidak ka-ka asüba ajanga state nung iba nungi indang indanga jembitettsü puteta caseload 23,350 alitsü. tashidak agi meneper asür nisung atema-a mongka agütsür. Iba "Tanü nisung 113 dak 441 kumogo aser item rongnung Nagaland Chief Minister, Neiphiu Rio-i Nagaland COVID Information App yagi tamshirtem indang data COVID-19 positive liasü - nisung 14 bo danga tashidak agi App tenzüktsüba noksa nung angur. -

Full, the Contractors Have No Right to Claim for Compensation

th 24 Friday 11 June | 30 Shawwal | 1442 Hijri | Vol:24 | Issue: 136 | Pages:08 | Price: `3 www.kashmirobserver.net twitter.com / kashmirobserver facebook.com/kashmirobserver Postal Regn: L/159/KO/SK/2014-2016 3 CITY 6 OVERCOMING THE 5 STATE PANDEMIC CRISIS MASKS MANDATORY IN SRINAGAR WILL TO SURVIVE: NONAGENARIAN Even as much as we may wear masks, BEATS CORONAVIRUS CITY, VIOLATORS TO BE FINED wash our hands repeatedly, maintain In a significant development, the Food Safety and Standards social distancing, boost our immunity The Covid-19 pandemic has caused innumerable deaths Authority of India (FSSAI) has authorised the Food Testing THINK and may even get vaccinated, as human across the world and it could easily be considered one of Laboratory (FTL) Dalgate, Srinagar to perform the testing/analysis beings we need the oxygen of hope to the worst events in modern history. Despite all, the... Widom J&K Logs 25 Corona Assembly Polls To Be You do not find the happy life. Held Next Year: Report You make it. Deaths, 1117 New Cases — Camilla Eyring Kimball Prepare In Advance Against Third Wave, HC To Govt Dr Aviral Vatsa NHS Scotland, UK Agencies remained unvaccinated Gas Leak Sparks he is also covered. Massive Fire SRINAGAR: Jammu and “The Government SRINAGAR: Several houses on Kashmir High Court has may also ensure estab- Third wave is inevitable, expressed hope that lishment of oxygen gen- unless vaccination is done Thursday were damaged in Noor- for > 40-50% people bagh area of Baramulla town after a the government would eration plants in every gas leak triggered a massive fire in a advance itself to face Government and al- Agencies complete its mandate of Which new variant will cause havoc remains unknown residential colony. -

Hindu Mahasabha to Organise 'Gaumutra Party'

Home / National / Hindu Mahasabha to organise 'gaumutra party' to fight coronavirus in India: Report The Mahasabha president Chakrapani Maharaj said a ‘gaumutra party’ on the lines of tea parties will be held DH Web Desk, MAR 04 2020, 19:41PM IST UPDATED: MAR 05 2020, 03:24AM IST Representative image (DH Photo) While the world is looking for ways and means to control the spread of the novel coronavirus, the Hindu Mahasabha has now popped up a new idea to contain the disease. Coronaviru… Total Confirmed 109.835 Confirmed Cases by Country/Regi on 80.699 Ma The Mahasabha president Chakrapani Maharaj said a ‘gaumutra party’ on the lines of tea parties will be held, according to a report by ThePrint. “Just like we organise tea parties, we have decided to organise a gaumutra party, wherein we will inform people about what is coronavirus and how, by consuming cow-related products, people can be saved from it,” Maharaj told the online news channel. Follow DH live coverage of coronavirus here “The event will have counters that will provide gaumutra for people to consume. At the same time, we will also put cow products like cow-dung cakes and agarbatti made from that. Upon using these, the virus will die immediately.” The Mahasabha president further told ThePrint that a big event will be organised in Delhi just past Holi to raise awareness among people as they believe the killing of animals was the cause of the spread of the disease. “We want to create awareness about jeev hatya (killing of beings), which is the main cause of coronavirus.