Old Strathcona: Building Character and Commerce in a Preservation District Karen L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheppard Block 10314 - 82 Ave, Edmonton, Ab

FOR LEASE SHEPPARD BLOCK 10314 - 82 AVE, EDMONTON, AB 544 - 1,900 SF OPPORTUNITY OFFICE SPACE Rare opportunity to lease within an iconic character building located in the heart of Whyte Avenue, which is one of Edmonton’s most iconic districts. Whyte Avenue is one of the highest pedestrian traffic areas and enjoys a unique mix of local boutique and regional and national tenant. Casey McClelland Casey.McClelland@ HIGHLIGHTS MarcusmMillichap.com +1 (587) 756 1560 • Vacancy 1: 1,900 SF, entire second floor office space with direct access, via stairwell, from Whyte Avenue • Vacancy 2: 544 SF office space on the 3rd floor Mike Hoffert • Elevator & stairwell access to all floors Mike.Hoffert@ MarcusMillichap.com • Located in the heart of Whyte Avenue +1 (587) 756 1550 • Area retailers include El Cortez restaurant, Starbucks, Hudson’s Pub, Dorinku Restaurant, and The Strathcona Hotel redevelopment (The Strathcona) • Building tenants include Craft & Cork Pub, Old Strathcona Business Association, Kevin Glass and Merchant Hospitality Group Kevin.Glass@ • Prime exposure commercial space in character building on Whyte Avenue MarcusMillichap.com • Building substantially renovated in 1995 to include elevator, sprinklers, new +1 (587) 756 1570 mechanical, etc. • Exposure to over 24,685 vehicles per day along Whyte Avenue web: MarcusMillichap.ca/MGHretail email: [email protected] TENANT LIST + STATS / SHEPPARD BLOCK 10314 - 82 AVE, EDMONTON, AB FLOOR UNIT SIZE TENANT U of A 5 minutes Basement BSMT 1,754 SF Craft & Cork Main Floor 100 2,150 -

WINTER 2015/2016! This Guide Gets Bigger and Better Every Year! We’Ve Packed This Year’S Winter Excitement Guide with Even More Events and Festivals

WELCOME TO WINTER 2015/2016! This guide gets bigger and better every year! We’ve packed this year’s Winter Excitement Guide with even more events and festivals. But keep your toque-covered ear to the ground for the spontaneous events that happen, like last year’s awesome #yegsnowfight We’re all working together, as a community, to think differently, to embrace the beauty of our snowy season, and to make Edmonton a great winter city. Edmonton’s community-led, award-winning WinterCity Strategy is our roadmap for reaching greatness. We are truly proud to say that we are on our way to realizing all the great potential our winters have to offer. New for this winter, we’ve got a blog for sharing ideas and experiences! Check it out at www.wintercityedmonton.ca If you haven’t joined us on Facebook and Twitter yet, we invite you to join the conversation. Let us know how you celebrate winter and be a part of the growing community that’s making Edmonton a great place to live, work and play in the wintertime. Now get out there and have some wintry fun! www.edmonton.ca/wintercitystrategy Facebook.com/WinterCityEdmonton @WinterCityYEG / #wintercityyeg Edmonton Ski Club Winter Warm-up Fundraiser Saturday, Oct 3, 2015 Edmonton Ski Club (9613 – 96 Avenue) www.edmontonskiclub.com Start winter with the ESC Winter Warm-up Fundraiser! Join us for a pig roast and family games. Visit our website for more details. International Walk to School Week (iWALK) Oct 5 – 9, 2015 www.shapeab.com iWALK is part of the Active & Safe Routes to School Program, promoting active travel to school! You can register online. -

Bus Network Route 008 Schedule

SUNDAY schedule guide information 8 Reading the Schedule ETS Real-Time To find the estimated times that a bus stops Track your bus anywhere anytime from your UNIVERSITY TO UNIVERSITY TO at a particular location, read down the column phone or computer using these recommended SERVICE FREQUENT ABBOTTSFIELD ABBOTTSFIELD under that location. real-time tools: edmonton.ca/realtime, To find the estimated times that a particular Google Maps, Transit App University 104 St & 101 St & 106 St & Coliseum Abbottsfield University 104 St & 101 St & 106 St & Coliseum Abbottsfield bus will stop at other locations, read across the TC 82 Ave Jasper Ave 118 Ave TC TC TC 82 Ave Jasper Ave 118 Ave TC TC row (left to right). F E D C B A F E D C B A Reading across the row tells you the time ETS Text & Ride TIMING POINTS TIMING required for the bus to travel between Text the bus stop number to 31100 or 2021 14, May Revised: timing points. 5:33 5:40 5:49 6:08 6:17 6:28 5:06 5:15 5:25 5:44 5:55 6:08 bus stop # [space] bus route # to receive 8ABBOTTSFIELD DOWNTOWN 5:53 6:00 6:09 6:28 6:37 6:48 5:21 5:30 5:40 5:59 6:10 6:23 your bus schedule by text message. 6:13 6:20 6:29 6:48 6:57 7:08 5:36 5:45 5:55 6:14 6:25 6:38 Example COLISEUM WHYTE AVE 6:33 6:40 6:49 7:08 7:17 7:28 5:51 6:00 6:10 6:29 6:40 6:53 For the schedule below, to arrive at 102 St & ETS BusLink NAIT UNIVERSITY 6:53 7:00 7:09 7:28 7:37 7:48 6:06 6:15 6:25 6:44 6:55 7:08 MacDonald Drive for 7:56 a.m., you will need Call 780-496-1600 for information about MACEWAN 7:13 7:20 7:29 7:48 7:57 8:08 6:21 6:30 6:40 6:59 7:10 7:23 to board the bus at Capilano Transit Centre when the next bus orLRT is scheduled to arrive. -

Duggan Volunteer Opportunities

Issue No. 319 FREE newsletter to all Duggan residents Compliments of the July/August Duggan Community League 2007 Duggan Details www.duggancommunity.ab.ca Pooling Resources and Pulling Together. One of the major problems with a volunteer along her block to inform everyone of some policies/procedures/resources, I’ve tried to share organization is the sheer amount of work it suspicious activity taking place along the street. the vision of where this all could lead, it’s up to entails. The funny thing is, in my exerience The effort, while a good start, unfortunately them to give just a little bit more of themselves probably 90% of the time is spent reinventing won’t have much effect unless we are willing to to benefit the whole. The DCL will act as a the wheel. pool our resources and start pulling together. central repository for ANY useful information (of course we could use some help to organize it Case in point…we have a very active soccer All this effort has wonderful short term effects, if it comes in). council which puts on an unbeatable tournament unfortunately I, like a majority of residents here, every year. To do this, they have to call volunteers, are probably planning on being here for the long A community league is about bringing people train people, arrange sponsors, purchase supplies haul. And over the long haul, I find that few together, for sharing, for empowering our and equipment, and a whole list of other things. people are willing to keep up the solitary work community. -

Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-Speaking Community in Alberta: 1882-2000

Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-speaking Community in Alberta Fifth Up-Date: 2008-2009 A project of the German-Canadian Association of Alberta © 2010 Compiler: Manfred Prokop Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-speaking Community in Alberta: 1882-2000. Fifth Up-Date: 2008-2009 In collaboration with the German-Canadian Association of Alberta German-Canadian Cultural Center, 8310 Roper Road, Edmonton, AB, Canada T6E 6E3 Compiler: Manfred Prokop 209 Tucker Boulevard, Okotoks, AB, Canada T1S 2K1 Phone/Fax: (403) 995-0321. E-Mail: [email protected] ISBN 0-9687876-0-6 © Manfred Prokop 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Quickstart ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Description of the Database ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Brief history of the project .................................................................................................................................... 2 Materials ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Sources ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Resources for Youth and Young Adults at Risk November 2019

Resources for Youth and Young Adults at Risk November 2019 Visit www.edmonton.cmha.ca to obtain a new copy if more than 6 months old. Accommodation / Basic Needs (also see Basic Needs list) Life Skills / Education / Employment Boyle Street Community Services Boyle Street Education Centre (Charter School) ..... 780-428-1420 Housing First (chronically homeless) ............... 780-424-4106 E4C - Hallway Cafe (16-24yrs) .................................. 780-619-5502 E4C - Inner City Youth Housing Project (14-17yrs) .. 780-479-7075 Edmonton John Howard Society Government of Alberta REE*START (15-22yrs) .................................. 780-428-7590 Emergency Income Support (24/7) ................ 780-644-5135 Edmonton’s Food Bank - Beyond Food ................... 780-425-2133 Hope Mission Edmonton - Youth Shelter (16-24yrs) The Elizabeth Fry Society of Edmonton (EFry) Herb Jamieson Centre (men; 18-60yrs) .......... 780-422-2018 Girls Empowered and Strong (12-17yrs) ........ 780-784-2200 Youth Empowerment & Support Services (YESS) YESS - Resource Centre (FKA: BEST) (15-24yrs) ... 780-468-7070 Nexus (15-21yrs) Bridging the Gap (employment; 15-30yrs) .......................................... 780-468-7070 YMCA - ..... 780-429-9622 Community Supports Legal / Advocacy Boyle McCauley Health Centre - Kindred House .... 780-424-4091 EFry - Courtworks - Adult, Youth, and Family .......... 780-422-4775 Outreach project for women and transgender individuals involved Legal Aid Alberta ................................................. 1-866-845-3425 in sex work; 18+yrs Youth Criminal Defence Office (24/7; 12-18yrs) 780-422-8383 Boyle Street Community Services .......................... 780-424-4106 Legislative Assembly of Alberta Boys and Girls Clubs Big Brothers Big Sisters ........ 780-424-8181 Child and Youth Advocate (CFSA status) ....... 780-422-6056 Crystal Kids Youth Centre - Drop-In Centre ........... -

Community Walking

WALK EDMONTON Walk Edmonton The Benefits of Walking Local Contacts Weather 780-468-4940 Walk Edmonton is an initiative bringing Edmontonians Strathcona Centre Walking… a healthy journey! City Information COMMUNITY WALKING MAP together to build a more walkable community by providing Community League Ranked the number one activity of choice among Canadians, Call 311 grass roots resources and building civic support. Check out walking is a prescription for improved health and wellness. 10139 – 87 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T6E 2P3 our website for links to other walking resources, maps, Walk briskly for 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week, and walking groups and places to walk in Edmonton. minimize your risk for cardiovascular disease, stroke, Type 2 780-439-1501 Emergency Strathcona [email protected] diabetes and some types of cancer. Additional benefits include edmonton.ca/walkedmonton strathconacommunity.ca Contacts 780-944-5339 weight management, blood pressure control and boosting good cholesterol (HDLs). Old Strathcona Foundation Police/Ambulance/Fire 780-433-5866 911 Other Walking Resources Other benefits of walking: [email protected] Police Complaint Line Releases the body’s tension and stress. Alberta Centre for Active Living • oldstrathconafoundation.ca 780-423-4567 centre4activeliving.ca • Refreshes the mind and body, especially when walking outdoors. Old Strathcona Business 780-427-6949 Association • Allows you to connect with your community. Canada Walks 780-437-4182 Offers an excellent way to socialize with -

WHERE Edmonton Magazine Media

MEDIA KIT 2019 WHAT IS WHERE Simply put, WHERE Edmonton is your best source of timely visitor information. Published locally since 1994, WHERE provides local information on the hottest and most essential shopping, dining, cultural attractions, and entertainment. WHERE IS WHERE WHERE Edmonton magazine is found in over 80 hotels and 250 pick-up locations throughout Edmonton and Greater Edmonton area. WHERE Magazine is found in 72 cities worldwide covering Asia, Europe, Australia, USA, and Canada. WHO IS WHERE The power of WHERE is its local depth. WHERE Edmonton’s magazine and online properties are created by local editors and staff who are passionate and knowledgeable about Edmonton and area. They know the best Edmonton has to offer, as they live it every day, not just on a one-week junket. We are proud to work in cooperation with all tourism organizations, hotel and concierge associations, and Chamber of Commerces in the promotion of our city. whereedmonton.com | infoedmonton.com The Strength of a Global Brand For 80+ years WHERE Magazine has been the go-to resource for authentic information that helps discerning travellers make the most of their trips. UNITED STATES Alaska New Orleans With over 100 million Atlanta *New York City Baltimore Northern Arizona readers globally, Boston Oahu WHERE Magazine is Charleston Orange County AUSTRALIA CANADA Charlotte Orlando Brisbane the largest and one of Calgary Chicago Palm Beach EUROPE Gold Coast the most recognized Canadian Rockies Colorado Philadelphia Melbourne Dallas/Fort Phoenix- Berlin Edmonton *Sydney travel media outlets. Worth Scottsdale Budapest Halifax Daytona Beach Reno-Tahoe Istanbul WHERE Canada and Muskoka Ft. -

Community & Collaborations

e4c Make Tax Time Pay Tax Filing boosts incomes “Many people simply don’t realize what is available and strengthens connections or what they are eligible for,” explains Lucas Stone, Financial Empowerment Coordinator,e4c. “MTTP It may be hard to see the connection between simply helps them access the things they are entitled to preparing taxes and strengthening communities, but receive.” envoySummer 2017 for the past 12 years, e4c Make Tax Time Pay (MTTP) has been doing exactly that. MTTP recruits volunteers Make Tax Time Pay’s tax season campaign is a team to work with low-income individuals and families to effort that includes partners such as 2-1-1 The Support provide free tax preparation and access to various Network, The United Way, Prosper Canada and the City benefits they may be eligible for. of Edmonton, who work together throughout the year to plan and prepare for tax season. The program arose out of the realization that one of the most effective ways to boost the income of low- Each MTTP site is designed to meet the unique needs income individuals and families is through tax filing of the community. Many of the volunteers are program and connecting them to benefits. alumni who consider working with MTTP a way to give back and make a tangible difference. Their efforts not MTTP directly addresses one of the core issues of only help people access much needed benefits and poverty – lack of income. refunds, but demonstrate what can be accomplished when communities work together. This past year, MTTP highlights included, Volunteers are • Individuals served 4,212 critical to the • Tax returns filed 4,567 success of the program, and in • Benefit applications completed 1,061 2017, more than and the program provided access to: 250 volunteers • Anticipated refunds totalling $1,785,466 donated their time at 25 community • GST rebates totalling $1,512,627 locations. -

Mccauley Neighbourhood

A HISTORY AND CONTEMPORARY INDIGENOUSOVERVIEW OF FIRST NATIONS AND MÉTIS LIFE IN THE MCCAULEY NEIGHBOURHOOD MCCAULEY WRITTEN BY MARILYN DUMONT EDITED AND PHOTOGRAPHED BY PAULA E. KIRMAN AboriginalBooklet_v9.indd 1 2016-11-07 9:59 AM INTRODUCTION “It’s important for people to learn about Indigenous history in Edmonton because they were not taught our history in schools so there is a vacuum and dearth of history in Edmonton . People need to learn about the Treaties that were signed and how those agreements were supposed to govern rela- tions between First Nations and Canada plus the settlers who came to live on our lands. People need to know that if not for our con- tributions, Canada would look much differ- ent today and the relationship between us would probably be further strained.” CHIEF CALVIN BRUNEAU, PAPASCHASE CREE NATION SOCIETY 2 AboriginalBooklet_v9.indd 2 2016-11-07 9:59 AM McCauley is a central Edmonton three generations, Fort Edmonton neighbourhood that is bordered was a place where Métis culture in the north by 111 Avenue/ would thrive and their religious Norwood Boulevard, to the west beliefs, culture and traditions by 101 Street, and in the south would dominate the Alberta land- east by the LRT line and the Com- scape. oday, the Métis settlements monwealth Stadium. that evolved at Fort Edmonton, Lac Ste. Anne, and Ste. Albert are Before discussing the Indigenous distant reminders of their [The history of McCauley, it is import- Métis’] central role in the founding ant to recognize a general history of our province.” 1 of Indigenous settlement in the Edmonton area. -

Alberta Canada – Travel Trade Snapshot of Top Things to Do & Places to Stay

ALBERTA CANADA – TRAVEL TRADE SNAPSHOT OF TOP THINGS TO DO & PLACES TO STAY LOCATION SUMMER THINGS TO DO WINTER THINGS TO DO PLACES TO STAY BANFF NATIONAL PARK WILDLIFE SUMMER WILDLIFE WINTER LUXURY ACCOMMODATION (Canadian Rockies) Discover Banff & It’s Wildlife Tour Discover Banff & It’s Wildlife Tour Fairmont Banff Springs Lake Louise Grizzly Bear Sightseeing Gondola & Yamnuska Wolfdog Sanctuary Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise Airport gateway = Calgary Trail of The Great Bear Hike Moraine Lake Lodge Lake Louise International Yamnuska Wolfdog Sanctuary LOCAL ATTRACTIONS & ACTIVITIES Rimrock Resort & Spa Banff WINTER The Post Hotel Lake Louise Distance from Calgary = 2 hours LOCAL ATTRACTIONS & ACTIVITIES drive Banff Upper Hot Springs WILDERNESS LODGES & CABINS SUMMER Cave & Basin Tour Rail access = Rocky Banff Sightseeing Gondola Dogsledding with Kingmik Baker Creek Chalets Lake Louise Mountaineer summer only Banff Upper Hot Springs Soak Fairmont White Christmas festivities - Dec Deer Lodge Lake Louise Bow River Rafting & Float Tour Horse Sleigh Rides Lake Louise Num-Ti-Jar (summer only) LL banfflakelouise.com Bow River Walking Trails Ice Magic – Ice Carving Festival – Jan Paradise Lodge & Bungalows Canoe on Lake Louise & Moraine Lake Ice skate on Lake Louise Shadow Lake Lodge (hike in only) Canoe on Vermillion Lakes Johnston Canyon Icewalk Skoki Lodge (hike in only) LL Cave & Basin Tour Lake Louise High Tea Storm Mountain Lodge & Cabins Golf at Banff Springs Golf Course Shopping Banff Avenue Heli Hiking -

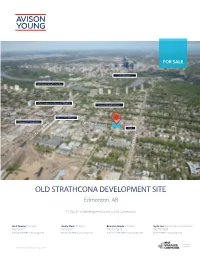

OLD STRATHCONA DEVELOPMENT SITE Edmonton, AB

FOR SALE Downtown Kinsmen Sports Centre Old Strathcona Farmers’ Market King Edward School Roots On Whyte Shoppers Drug Mart Whyte Avenue CIBC Gateway Blvd 99 Street OLD STRATHCONA DEVELOPMENT SITE Edmonton, AB 21,764 SF of development land in Old Strathcona Amit Grover, Principal Jandip Deol, Principal Brandon Imada, Associate Jayde Lee, Administrative Coordinator 780.540.5421 780.540.5422 780.702.5826 780.758.9655 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.avisonyoung.com OPPORTUNITY Old Strathcona remains as one of the most popular infill developments neighbourhoods across the city, with numerous residential and commercial developments underway along Whyte Avenue. The Old Strathcona Development 99 Street Site presents an excellent opportunity to differentiate by developing a unique mixed use project along one of Edmonton’s most lively streets. Several very successful new developments have recently been complete or are in development including: Raymond Block, Strathcona Hotel, Southpark On Whyte, The Mezzo, The Trax, Peli at Scona, and more, further proving the viability of this neighbourhood for increased rental density. With the close proximity to the University of Alberta, and a plethora of retail amenities, Strathcona proves to be one of Edmonton’s most resilient rental markets. Whyte Avenue Former Shell Gas Station site that was decommissioned in 2009 (tanks removed). Brownfield Redevelopment Grant Program approved for the site remediation. PROPERTY SUMMARY MUNICIPAL ADDRESS 9950 - 82 Avenue Old Strathcona Development Land LEGAL ADDRESS Plan I, Block 71, Lot 1-5 HIGHLIGHTS Edmonton, AB NEIGHBOURHOOD Old Strathcona Close to the River Valley and LOCATION ZONING Millcreek Ravine CB2 Old Strathcona is one of Edmonton’s liveliest neighbourhoods and SITE SIZE is home to numerous arts and entertainment facilities, as well as Future LRT local shopping options for residents and nearby University of Alberta 21,764 SF Walking distance to numerous restaurants, boutique clothing store students.