The Piper and the Physicist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Blake “The Chimney Sweeper” 1 When My Mother Died I

William Blake “The Chimney Sweeper” 1 “The Chimney Sweeper” 2 When my mother died I was very young. A little black thing among the snow: And my father sold me while yet my tongue Crying weep, weep, in notes of woe! Could scarcely cry “ ‘weep! ‘weep! ‘weep! ‘weep!” Where are thy father & mother? say? So your chimneys I sweep & in soot I sleep. They are both gone up to the church to pray. There’s little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head, Because I was happy upon the heath, That curl’d like a lamb’s back, was shav’d: so I said: And smil’d among the winters snow: “Hush, Tom! never mind it, for when your head’s bare They clothed me in the clothes of death, You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair.” And taught me to sing the notes of woe. And so he was quiet & that very night, And because I am happy, & dance & sing, As Tom was a-sleeping, he had such a sight! They think they have done me no injury: That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned & Jack, And are gone to praise God & his Priest & King Were all of them lock’d up in coffi ns of black. Who make up a heaven of our misery. And by came an Angel who had a bright key, And he open’d the coffi ns & set them all free; Then down a green plain leaping, laughing, they run, And wash in a river, and shine in the Sun. Then naked & white, all their bags left behind, They rise upon clouds and sport in the wind; And the Angel told Tom, if he’d be a good boy, 1 Songs of Innocence He’d have God for his father & never want joy. -

William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: from Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1977 William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W. Winkleblack Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Winkleblack, Robert W., "William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence" (1977). Masters Theses. 3328. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3328 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. �S"Date J /_'117 Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ��--��- Date Author pdm WILLIAM BLAKE'S SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE: - FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE TO WISE INNOCENCE (TITLE) BY Robert W . -

Inseparable Interplay Between Poetry and Picture in Blake's Multimedia Art

PETER HEATH All Text and No Image Makes Blake a Dull Artist: Inseparable Interplay Between Poetry and Picture in Blake's Multimedia Art W.J.T. Mitchell opens his book Blake's Composite Art by saying that “it has become superfluous to argue that Blake's poems need to be read with their accompanying illustrations” (3); in his mind, the fact that Blake's work consists of both text and image is obvious, and he sets out to define when and how the two media function independently of one another. However, an appraisal of prominent anthologies like The Norton Anthology of English Literature and Duncan Wu's Romanticism shows that Mitchell's sentiment is not universal, as these collections display Blake's Songs of Innocence and Experience as primarily poetic texts, and include the illuminated plates for very few of the works.1 These seldom-presented pictorial accompaniments suggests that the visual aspect is secondary; 1 The Longman Anthology of British Literature features more of Blake's illuminations than the Norton and Romanticism, including art for ten of Blake's Songs. It does not include all of the “accompanying illustrations,” however, suggesting that the Longman editors still do not see the images as essential. at the EDGE http://journals.library.mun.ca/ate Volume 1 (2010) 93 clearly anthology editors, who are at least partially responsible for constructing canons for educational institutions, do not agree with Mitchell’s notion that we obviously must (and do) read Blake’s poems and illuminations together. Mitchell rationalizes the segregated study of Blake by suggesting that his “composite art is, to some extent, not an indissoluble unity, but an interaction between two vigorously independent modes of expression” (3), a statement that in fact undoes itself. -

The Visionary Company

WILLIAM BLAKE 49 rible world offering no compensations for such denial, The] can bear reality no longer and with a shriek flees back "unhinder' d" into her paradise. It will turn in time into a dungeon of Ulro for her, by the law of Blake's dialectic, for "where man is not, nature is barren"and The] has refused to become man. The pleasures of reading The Book of Thel, once the poem is understood, are very nearly unique among the pleasures of litera ture. Though the poem ends in voluntary negation, its tone until the vehement last section is a technical triumph over the problem of depicting a Beulah world in which all contraries are equally true. Thel's world is precariously beautiful; one false phrase and its looking-glass reality would be shattered, yet Blake's diction re mains firm even as he sets forth a vision of fragility. Had Thel been able to maintain herself in Experience, she might have re covered Innocence within it. The poem's last plate shows a serpent guided by three children who ride upon him, as a final emblem of sexual Generation tamed by the Innocent vision. The mood of the poem culminates in regret, which the poem's earlier tone prophe sied. VISIONS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF ALBION The heroine of Visions of the Daughters of Albion ( 1793), Oothoon, is the redemption of the timid virgin Thel. Thel's final griefwas only pathetic, and her failure of will a doom to vegetative self-absorption. Oothoon's fate has the dignity of the tragic. -

'O Rose Thou Art Sick': Floral Symbolism in William Blake's Poetry

‘O Rose Thou Art Sick’: Floral Symbolism in William Blake’s Poetry Noelia Malla1 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Available Online March 2014 The primary aim of this paper is to analyse the symbolic implications of Key words: floral imagery in William Blake’s poetry. More specifically, this study William Blake; explores the process of floral (re)signification of William Blake’s Songs of Songs of Innocence and of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794) as case studies. Since Experience; “Without contraries [there] is no progression” (Marriage of Heaven and The Sick Rose; Hell, plate 3), it can be argued that the Songs represent contrary aspects floral imagery. of the human condition that far from contradicting each other, establish a static contrast of shifting tensions and revaluation of the flower-image not only as a perfect symbol of the “vegetable” life rooted to the Earth but also as a figure longing to be free. In some sense at some level, the poetic- prophetic voice asserts in the Songs of Experience the state of corruption where man has fallen into. Ultimately, this study will explore how the failure to overcome the contrast that is suggested in the Songs will be deepened by the tragedy of Thel, which is symbolized by all unborn forces of life, all sterile seeds as an ultimate means of metaphorical regeneration throughout Poetry which constitutes in itself the Poet Prophet’s own means of transcending through art. William Blake (1757-1827) was the first English poet to work out the revolutionary structure of imagery that (re)signifies through the Romantic poetry. -

A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 1996

ARTICLE William Blake and His Circle: A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 1996 G. E. Bentley, Jr., Keiko Aoyama Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 30, Issue 4, Spring 1997, pp. 121-152 William Blake and His Circle: In general, Keiko Aoyama is responsible for works in Japa nese, and I am greatly indebted to her for her meticulous A Checklist of Publications and accuracy and her patience in translating the words and con ventions of Japan into our very different context. Discoveries in 1996 I take Blake Books (1977) and Blake Books Supplement (1995), faute de mieux, to be the standard bibliographical authorities on Blake1 and have noted significant differences BY G. E. BENTLEY, JR. from them. With the Assistance ofKeiko Aoyama for N.b. I have made no attempt to record manuscripts, type Japanese Publications scripts, computer printouts, radio or television broadcasts, calendars, music, pillows,2 posters,3 published scores,"1 re 5 he annual checklist of scholarship and discoveries con corded readings and singings, rubber stamps, Tshirts, 6 Tcerning William Blake and his circle records publica tatoos, video recordings, or email related to Blake. tions for the current year (say, 1996) and those for previ The chief indices used to discover what relevant works ous years which are not recorded in Blake Books (1977) and have been published were (1) Annual Bibliography of En Blake Books Supplement (1995). The organization of the glish Language and Literature, LXVIII for 1993 (1995), pp. checklist is as follows: 37477 (#58165772); (2) BHA: Bibliography of the His tory of Art, Bibliographic d'Histoire de l'Art (1995); (3) Division I: William Blake Books in Print (October 1996); (4) British Humanities In dex 1995 (1996); (5) English and General Literature Index Part I: Editions, Translations, and Facsimiles of 19001933 (1934), pp. -

Year 8 Spring Term English School Booklet

Module 2 Year 8: Romantic Poetry Songs of Innocence and Experience, William Blake Name: Teacher: 1 The Industrial Revolution Industrial An industrial system or product is one that He rejected all items made using industrial (adjective) uses machinery, usually on a large scale. methods. Natural Natural things exist or occur in nature and She appreciated the natural world when she left (adjective) are not made or caused by people. the chaos of London. William Blake lived from 28 November 1757 until 12 August 1827. At this time, Britain was undergoing huge change, mainly because of the growth of the British Empire and the start of the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution was a time when factories began to be built and the country changed forever. The countryside, natural and rural settings were particularly threatened and many people did not believe they were important anymore because they wanted the money and the jobs in the city. The population of Britain grew rapidly during this period, from around 5 million people in 1700 to nearly 9 million by 1801. Many people left the countryside to seek out new job opportunities in nearby towns and cities. Others arrived from further away: from rural areas in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, for example, and from across large areas of continental Europe. As cities expanded, they grew into centres of pollution and poverty. There were good things about the Industrial Revolution, but not for the average person – the rich factory owners and international traders began to make huge sums of money, and the gap between rich and poor began to widen as a result. -

Autoeroticism and Blake : O Rose Art Thou Sick!?

Title Autoeroticism and Blake : O Rose Art Thou Sick!? Author(s) 瀬名波, 栄潤 Citation 北海道大學文學部紀要, 46(1), 85-109 Issue Date 1997-09-30 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/33690 Type bulletin (article) File Information 46(1)_PL85-109.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Autoeroticism and Blake: o Rose Art Thou Sick !? ::t-l'xU5--1v7:'At7"Y1.1 : jO J:, jOM ~i~f1g Iv "[·v) ~ Q):iJ'o I William Blake's "The Sick Rose" in Songs of Experience has provoked various interpretations since its publication in 1794, but, when it comes to woman's pain and woman's pleasure, the poem stilI has plenty of room for further analysis. A woman is symbolically presented, as Rose, in the caged situation and, being unable to free herself, finds an alternative pleasure. In this article, I will closely examine the poem and its relation to the plate and verify that Blake's reference to a woman's masturbation produces multitudinous interpre tations representing his ideas, society, man, and woman. The poem has endured various interpretations due to its brief eight-line length (which makes the poem symbolic and suggestive), Blake's complicated ideas about the individual and society, and the relation of the poem to the plate. As Leopold Damrosch, Jr. says, H The poem can be read in at least four ways -naturalistic (roses do decay), psychosexual, sociopolitical, and metaphysical- and while one is not obliged to read it in all of these ways, the poem is richer and -85 more interesting (and certainly more Blakean) if one does so" (80). -

A Poetic Sense of Evil Xiao-Xuan DU

2020 2nd International Conference on Arts, Humanity and Economics, Management (AHEM 2020) ISBN: 978-1-60595-685-5 A Poetic Sense of Evil 1,a,* Xiao-xuan DU 1School of Foreign Languages, Dalian Neusoft University of Information, Dalian, Liaoning, China [email protected] *corresponding author Keywords: Evil, Good, Natural state. Abstract. This paper is intended to analyze the theme of William Blake’s poem The Tyger in the perspective of “evil”. The interpretation comprises of three sections, namely a brief introduction to the author—William Blake, analysis of this poem and comparisons with the other two poems written by Blake, reaching to the conclusion that “evil” is a natural state and an inseparable part of social progress. 1. Introduction The Tyger was first published in William Blake’s first volume of Songs of Experience in 1794. The Songs of Experience was written to complement Blake’s earlier collection, Songs of Innocence (1789). The Tyger could be seen as the later volume’s answer to The Lamb, the “innocent” poem in the earlier volume. The Tyger is the best known of all William Blake’s poems and is known as the most cryptic lyrical poem of English literature. The poem’s opening line, ‘Tyger Tyger, burning bright’ is one of the most famous opening lines in English poetry. The poem expresses great astonishment about the creation of a fiery tiger. There is limitless depth in the poem, for with every subsequent reading, it can conjure fresh images in the mind of the receptive readers. There are many interpretations of this poem. -

Critical Discourse Analysis of Blake's “AH SUN-FLOWER!”

New Horizons, Vol.12, No.2, 2018, pp 59-75 DOI:10.2.9270/NH.12.2(18).05 FaircLOuGh’s three-DiMensiOnaL MODeL: criticaL DiscOurse anaLYsis OF bLake’s “AH SUN-FLOWER!” Prof. shahbaz afzal bezar, Dr. Mahmood ahmad azhar, and Dr. Muhammad saeed akhter abstract Discourse is language in use, or language used for communicative purposes. It relates to social structures, practices, and social change. In Critical Discourse Analyses (CDA), the link between discourse and society/context is mediated. There is a dialectical relationship between discourse and ideology. Ideology is a system of ideas especially social, political or religious views shared by a social group or movement. This study is qualitative in nature, rooted in critical discourse analysis, especially, Fairclough’s three-dimensional model- ‘Description’ (lexical, graphological, grammatical, and phonological level) and ‘Interpretation’ of Blake’s “Ah Sun-flower!” which lead towards ‘Explanation’ that explores the relation of this poem with social structures of authority and unequal power relations of Blake contemporary society. The authoritative, repressive and patriarchal ideology of the 18 th century has been explored from this poem. The concept of the Golden Age of this poem is linked with CDA’s dream of problem-free society; ‘Youth’ and ‘Virgin’ have been analyzed in the context of the institution of the love of 18 th century. Keywords: Critical Discourse Analyses, Ideology, Social Change, Description, Interpretation, Power Relations. intrODuctiOn The beauty of literature lies in the fact that the readers interpret it in the perspective of the social, political, and religious condition of the period in which it is produced. -

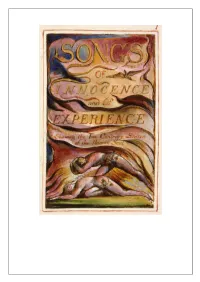

Songs of Innocence and of Experience by William Blake

SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE BY WILLIAM BLAKE 1789-1794 Songs Of Innocence And Of Experience By William Blake. This edition was created and published by Global Grey 2014. ©GlobalGrey 2014 Get more free eBooks at: www.globalgrey.co.uk No account needed, no registration, no payment 1 SONGS OF INNOCENCE INTRODUCTION Piping down the valleys wild Piping songs of pleasant glee On a cloud I saw a child. And he laughing said to me. Pipe a song about a Lamb: So I piped with merry chear, Piper pipe that song again— So I piped, he wept to hear. Drop thy pipe thy happy pipe Sing thy songs of happy chear, 2 So I sung the same again While he wept with joy to hear. Piper sit thee down and write In a book that all may read— So he vanish’d from my sight, And I pluck’d a hollow reed. And I made a rural pen, And I stain’d the water clear, And I wrote my happy songs, Every child may joy to hear 3 THE SHEPHERD How sweet is the Shepherds sweet lot, From the morn to the evening he strays: He shall follow his sheep all the day And his tongue shall be filled with praise. For he hears the lambs innocent call. And he hears the ewes tender reply. He is watchful while they are in peace, For they know when their Shepherd is nigh. 4 THE ECCHOING GREEN The Sun does arise, And make happy the skies. The merry bells ring, To welcome the Spring. -

William Blake ( 1757-1827)

William Blake ( 1757-1827) "And I made a rural pen, " "0 Earth. 0 Earth, returnl And I stained the water clear, "Arise from out the dewy grass. And J wrote my happy songs "Night is worn. Every child may joy to hear." "And the mom ("Introduction". Songs of Innocence) "Rises from the slumberous mass." ("Introduction''. Songs of Experience! 19 Chapter- 2 WILLIAM BLAKE "And I made a rural pen, And I stain'd the water clear, And I wrote my happy songs Every child may joy to hear. "1 "Then come home, my children, the sun is gone down, And the dews of night arise; Your spring and your day are wasted in play, · And your winter and night in disguise. "1 Recent researches have shown the special importance and significance of childhood in romantic poetry. Blake, being a harbinger of romanticism, had engraved childhood as a state of unalloyed joy in his Songs of Innocence. And among the romantics, be was perhaps the first to have discovered childhood. His inspiration was of course the Bible where he had seen the image of the innocent, its joy and all pure image of little, gentle Jesus. That image ignited the very ·imagination of Blake, the painter and engraver. And with his illuntined mind, he translated that image once more in his poetry, Songs of Innocence. Among the records of an early meeting of the Blake Society on 12th August, 1912 there occurs the following passage : 20 "A pleasing incident of the occasion was the presence of a very pretty robin, which hopped about unconcernedly on the terrace in front of the house and among the members while the papers were being read..