A Counterfactual Obama Presidency: Policy Progress with Less Damage to the Democratic Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio ______) Ohio A

Case: 1:18-cv-00357-TSB Doc #: 1 Filed: 05/23/18 Page: 1 of 44 PAGEID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO __________________________________________ ) OHIO A. PHILIP RANDOLPH INSTITUTE, ) LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OF OHIO, ) LINDA GOLDENHAR, DOUGLAS BURKS, ) SARAH INSKEEP, CYNTHIA LIBSTER, ) KATHRYN DEITSCH, LUANN BOOTHE, ) MARK JOHN GRIFFITHS, LAWRENCE ) NADLER, CHITRA WALKER, RIA MEGNIN, ) ANDREW HARRIS, AARON DAGRES, ) COMPLAINT ELIZABETH MYER, ERIN MULLINS, TERESA ) THOBABEN, and CONSTANCE RUBIN, ) No. ) Plaintiffs, ) Three-Judge Court Requested ) Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2284(a) v. ) ) JOHN KASICH, Governor of Ohio, ) JON HUSTED, Secretary of State of Ohio, ) KIRK SCHURING, Speaker Pro Tempore of ) the Ohio House of Representatives, and LARRY ) OBHOF, President of the Ohio Senate, in their ) official capacities, ) ) Defendants. ) __________________________________________) Case: 1:18-cv-00357-TSB Doc #: 1 Filed: 05/23/18 Page: 2 of 44 PAGEID #: 2 INTRODUCTION 1. This case is a challenge to Ohio’s current United States congressional redistricting plan (the “plan” or “map”) as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander that violates the First Amendment, the Fourteenth Amendment, and Article I of the United States Constitution. 2. The current Ohio map is one of the most egregious gerrymanders in recent history. The map was designed to create an Ohio congressional delegation with a 12 to 4 Republican advantage—and lock it in for a decade. It has performed exactly as its architects planned, including in 2012, when President Barack Obama won the state. In statewide and national elections, Ohio typically swings from Democrats to Republicans. In this decade, Republicans have secured 51% to 59% of the total statewide vote in congressional elections. -

2016 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 A LETTER FROM LPB A LETTER FROM PRESIDENT & CEO FRIENDS OF LPB BETH COURTNEY 2016 BOARD CHAIR DAN HARE This year the people of Louisiana turned to LPB as a trust- Friends of Louisiana Public Broadcasting is a nonprofit cor- ed voice in a time of turbulence. Together we weathered the poration operating solely to support the Louisiana Educational flood waters in both North and South Louisiana. LPB shared Television Authority (LPB). Friends of LPB is organized to ad- stories of courage, collected items and delivered aid to those vance the educational and cultural enrichment of all citizens in need. More than 80 public television stations across the and to assist in making the benefits of quality public television country sent materials and supplies for us to distribute. Our available to all the people of Louisiana. The organization is on-air pledge drive included appeals for the teachers and governed by a volunteer board of directors consisting of 28 classrooms that were flooded. We distributed over 2,000 individuals from across the state, with the tremendous support books and we continue to work with early childhood centers of an amazing staff of four employees who perform the day- in the areas of most critical need. Once again LPB continues to-day and often evening operations. its mission of being a safe haven for families while also serv- At the 2016 PBS Annual Meeting, Rose Long, one of our ing as the state’s largest classroom. long-time board members, was honored with the Public In addition to our role in public safety, we remain a place Broadcasting System’s Grassroots Advocacy National Volun- for the public to have civil discourse. -

Commissioner Mcdonald Named As Delegate to 2016 Republican

244 Washington St S.W. Contact: Lauren “Bubba” McDonald Georgia Public Service Atlanta, Georgia 30334 Phone: 404-463-4260 Phone: 404-656-4501 www.psc.state.ga.us Commission Toll free:1- 800-282-5813 Fax: 404-656-2341 For Immediate Release 11-16 NEWS RELEASE FROM THE OFFICE OF COMMISSIONER LAUREN “BUBBA” MCDONALD Commissioner McDonald Selected as Delegate to Republican National Convention June 7, 2016 – (ATLANTA) – The Georgia Republican Party Convention has selected Commissioner Lauren “Bubba” McDonald as one of 31 Georgia Republican Party delegates to the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Ohio from July 18-21, 2016. McDonald will be an at-large delegate. McDonald is currently the Vice-chair of the Georgia Public Service Commission. McDonald serves as a state co-chair in the Georgians for Trump organization. As the only elected statewide constitutional officer to have endorsed Donald Trump, McDonald will use that influence with the Trump organization to benefit the Georgia Republican Party and the citizens of Georgia should Trump win the nomination and be elected President. This is Commissioner McDonald’s first ever selection as a delegate to a National Convention. “This is a great honor and I am proud to represent my state and my party at this convention,” said McDonald. “It has always been a dream of mine to someday attend the convention as a full- fledged delegate.” Since 2008 McDonald has run two successful statewide elections as a Republican representing District Four. McDonald was first appointed to the Georgia Public Service Commission in 1998 by Governor Zell Miller. Since 1992, McDonald has helped to finance and recruit Republicans for office. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Box Number: M 17 (Otw./R?C<O R 15

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics REMOVAL NOTICE Removed from: S\>QQClt\es, j'Ot1Lt Mc..C.luv\Uj I ( 1 'f<-f Accession: Box Number: m17 (otw./r?C<O r 15 z,cr ~ fftt«r Rt (Jub/t'c CV1 Removed to: Oversized Photographs Box I (Circle one) Oversized Publications Box Campaign Material Box Oversized Newsprint Box Personal Effects Box Mem~rabilia Btm- _:£__ Oversized Flats [Posters, Handbills, etc] Box Political Cartoons Box -- Textiles Box Photograph Collection Box \ ,,,,,,,.... 4" Size: X , 2 5 >< • 7J Format: Pi v'\ Description: Ret k~v\o.>1 Dat~: rn4 > ol ""'~\ t ~', Subject Terms (ifanyJ. Restrictions: none Remarks: Place one copy with removed item Place one copy in original folder File one copy in file Page 1 of 188 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics REMOVAL NOTICE Date: from: ~pe (!c_~J Jt:'~C. e rf)c C..lun ji l'7°1 Accession: Box Number: B 0 ~ \ t ro 'I"' l'l • l 5 6L/ /;;Ff So'"":t-h.v\V"'\ 'R-e._plA l; co-"' ~~~~ Removed to: Oversized Photographs Box C.O~t-('U"UL.. ( C ircle one) Oversized Publications Box Campaign Material Box Oversized Newsprint Box Personal Effects Box Memorabilia -:tJ1f X Oversized Flats [Posters, Handbills, etc] Box __ Political Cartoons Box Textiles Box Photograph Collection Box Restrictions: none Remarks: Place one copy with removed item Place one copy in original folder File one copy in file Page 2 of 188 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu WH"A T , S .INN AT ENGL ..ISH MANOR AND LA.KE .RA.BUN .INNS ..IN 1 994 FOR THOSE OF YOU #HO HAVEN'T BEEN OUR t;UESTS IN THE PAST OR HAVEN'T VISITED US RECENTLY, ENt;LISH ANO I #OULO LIKE TO ACQUAINT YOU ANO BRINE; YOU UP TO DATE. -

Sexual Assault in the Political Sphere Robert Larsen University of Nebraska-Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Spring 3-12-2018 Sexual Assault in the Political Sphere Robert Larsen University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Larsen, Robert, "Sexual Assault in the Political Sphere" (2018). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 46. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/46 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SEXUAL ASSAULT IN THE POLITICAL SPHERE An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln by Robert E. Larsen, BA Political Science College of Arts and Sciences March 12, 2018 Faculty Mentors: John Gruhl, PhD, Political Science 1 Abstract This project sought to analyze how sexual assault in the political sphere is perceived and treated in contemporary society in the United States of America. The thesis analyzed eight cases of sexual misconduct, including six from the past thirty years. In each case, the reaction of party and social leaders, of the politician’s constituents and of the politician himself were looked at, as well as the consequences the politician faced. The results were then analyzed side-by-side to discover similarities and differences between ho cases of sexual assault allegations were treated and in terms of what happened to the politician after the allegations came out. -

How an Outdated Electoral Structure Has Led to Political Polarization in the United States

The United States Election System: How an Outdated Electoral Structure has led to Political Polarization in the United States by Jake Fitzharris A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Political Science and Psychology (Honors Associate) Presented January 24, 2019 Commencement June 2019 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jake Fitzharris for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Political Science and Psychology presented on January 24, 2019. Title: The United States Election System: How an Outdated Electoral Structure has led to Political Polarization in the United States. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Christopher Nichols Political Polarization in the United States is at a level higher today than at any point in the past few decades. Possible causes of this rise in polarization have been provided from various sources, including explanations such as mass media and income inequality. Through historical analysis and a wide literature review, this thesis explores a major factor in political polarization, the United States election system. The thesis argues that the election system in the United States exacerbates the intensely polarized political climate of the modern day United States in three main ways: the electoral college, which produces the persisting two party system, primary elections, which reinforce extreme candidate views, and districting, which tends to increase politically uniform districts and lead candidates to position themselves at the poles rather than in the center. The thesis concludes that the only way to eliminate political polarization stemming from all of these sources would be to implement a unique proportional representation system for the United States. -

The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network

PLATFORMS AND OUTSIDERS IN PARTY NETWORKS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE DIGITAL POLITICAL ADVERTISING NETWORK Bridget Barrett A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Daniel Kreiss Adam Saffer Adam Sheingate © 2020 Bridget Barrett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bridget Barrett: Platforms and Outsiders in Party Networks: The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network (Under the direction of Daniel Kreiss) Scholars seldom examine the companies that campaigns hire to run digital advertising. This thesis presents the first network analysis of relationships between federal political committees (n = 2,077) and the companies they hired for electoral digital political advertising services (n = 1,034) across 13 years (2003–2016) and three election cycles (2008, 2012, and 2016). The network expanded from 333 nodes in 2008 to 2,202 nodes in 2016. In 2012 and 2016, Facebook and Google had the highest normalized betweenness centrality (.34 and .27 in 2012 and .55 and .24 in 2016 respectively). Given their positions in the network, Facebook and Google should be considered consequential members of party networks. Of advertising agencies hired in the 2016 electoral cycle, 23% had no declared political specialization and were hired disproportionately by non-incumbents. The thesis argues their motivations may not be as well-aligned with party goals as those of established political professionals. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................................... V POLITICAL CONSULTING AND PARTY NETWORKS ............................................................................... -

PATRIOTS for TRUMP DINNER October 9Th, 2020 Tommy Gun Warehouse at the Rod of Iron Freedom Festival Grounds 105 Kahr Ave

PATRIOTS FOR TRUMP DINNER October 9th, 2020 Tommy Gun Warehouse at the Rod of Iron Freedom Festival Grounds 105 Kahr Ave. Greeley, PA 18425 $5,000 - Diamond Sponsor: Table for 10, VIP access for 4. $150 – Patriot: Per Person ☐ ☐ $3,000 - Gold: Table for 10, VIP access for 2. $75 – Supporter: Per Person ☐ ☐ $2,000 - Silver: Table for 10, VIP access for 1. No, I cannot attend, but would like to contribute $_____________. ☐ ☐ $1,000 - Bronze: Table for 10. ☐ For information on joining the Trump Victory Finance Committee contact [email protected] CONTRIBUTOR INFORMATION Please fill out every field. This information is required to contribute. Prefix First Name Last Name Preferred Name Employer (Required) Occupation (Required) Address City State Zip Cell Phone Work Phone Home Phone Email Signature (Required) JOINT CONTRIBUTOR INFORMATION (If applicable) Please fill out every field if you are giving from a joint account. Prefix First Name Last Name Preferred Name Employer (Required) Occupation (Required) Cell Phone Work Phone Home Phone Email Joint Contributor Signature (Required if Joint) PAYMENT INFORMATION ☐ Pay by personal check. Please make personal checks payable to Trump Victory, ☐ Pay by personal credit card *All credit cards processed by WinRed. ☐ Visa ☐ MasterCard ☐ American Express ☐ Discover Name on personal credit card Card Number Contribution Amount: $ Expiration Date Security Code TRACKING & RETURN INFORMATION Fundraiser ID (if applicable) 4683 Event Code (if applicable) E20PA006 Please send completed contribution forms and checks to Trump Victory: 310 First Street, SE; Washington, DC 20003. Paid for by Trump Victory, a joint fundraising committee authorized by and composed of Donald J. -

Voters' Pamphlet Primary Election 2020 for Lane County

Voters’ Pamphlet Oregon Primary Election May 19, 2020 Certificate of Correctness I, Bev Clarno, Secretary of State of the State of Oregon, do hereby certify that this guide has been correctly prepared in accordance with the law in order to assist electors in voting at the Primary Election to be held throughout the State on May 19, 2020. Witness my hand and the Seal of the State of Oregon in Salem, Oregon, this 6th day of April, 2020. Bev Clarno Oregon Secretary of State Oregon votes by mail. Ballots will be mailed to registered voters beginning April 29. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE ELECTIONS DIVISION STEPHEN N. TROUT BEV CLARNO DIRECTOR SECRETARY OF STATE 255 CAPITOL ST NE, SUITE 501 SALEM, OREGON 97310 (503) 986-1518 Dear Oregon Voter, The information this Voters’ Pamphlet provides is designed to assist you in participating in the May 19, 2020, Primary Election. Primary elections serve two main purposes. The first is for all voters to be able to cast ballots for candidates for nonpartisan offices like judges and some county and other local offices. The second is for the voters registered with a major political party to select their nominees for partisan office like US President. Those registered as not affiliated with a political party, or registered with a minor party (Constitution, Independent, Libertarian, Pacific Green, Progressive, Working Families) will receive a ballot that includes only nonpartisan offices. The US Supreme Court has ruled that political parties get to decide who votes in their primaries so unless you are registered as a Republican or Democrat you will not have candidates for President or any partisan office on your May Primary ballot. -

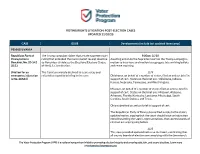

Voting Rights Litigation: Post-Election Cases Updated 11/10/20

VOTING RIGHTS LITIGATION: POST-ELECTION CASES UPDATED 11/10/20 CASE ISSUE Developments (include last updated timestamp) PENNSYLVANIA Republican Party of The Trump campaign claims that a state supreme court 9:00am 11/10 Pennsylvania v. ruling that extended the mail-in ballot receipt deadline Awaiting action by the Supreme Court on the Trump campaign’s Boockvar, No. 20-542 to November 6 violates the Elections/Electors Clause motion to intervene and motion to segregate late-arriving ballots (U.S.) of the U.S. Constitution. and cease counting. (Motion for an The Court previously declined to issue a stay and 11/9 emergency injunction refused to expedite briefing in the case. Oklahoma, on behalf of a number of states, filed an amicus brief in is No. 20A84) support of cert. States on the brief are: Oklahoma, Indiana, Kansas, Nebraska, Tennessee, and West Virginia. Missouri, on behalf of a number of states, filed an amicus brief in support of cert. States on the brief are: Missouri, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Texas. Ohio submitted an amicus brief in support of cert. The Republican Party of Pennsylvania filed a reply to the state’s updated notice, arguing that the court should issue an injunction notwithstanding the state’s representations that county boards of election are segregating ballots. 11/8 The state provided updated notice to the Court, confirming that all county boards of election are complying with the Secretary’s The Voter Protection Program (VPP) is a national nonpartisan initiative promoting election integrity and ensuring safe, fair, and secure elections. -

Volume 8 Issue 3 8 Issue Volume 2019 Fall

Birmingham City School of Law BritishBritish JoJournalurnal ofof British Journal of American Legal Studies | Volume 7 Issue 1 7 Issue Legal Studies | Volume British Journal of American British Journal of American Legal Studies | Volume 8 Issue 3 8 Issue Legal Studies | Volume British Journal of American AmericanAmerican LegalLegal StudiesStudies VolumeVolume 87 IssueIssue 31 FallSpring 2019 2018 ARTICLES SPECIAL ISSUE MERICAN OLITICS ISTORY AND AW ROSS ISCIPLINARY IALOGUE AFounding-Era P Socialism:, H The Original L Meaning: A C of the -Constitution’sD Postal D Clause Robert G. Natelson PapersToward presentedNatural Born to a Derivative conference Citizenship hosted by the Centre for American Legal Studies, BirminghamJohn Vlahoplus City University and the Monroe Centre, Reading University with the support of the Political Studies Association (PSA) ECN NetworkFelix Frankfurter and the American and the Law Politics Group and held at Birmingham City University on Monday,Thomas 30th HalperJuly 2018. SpecialFundamental Issue Editor:Rights Drin EarlyIlaria AmericanDi-Gioia, BirminghamCase Law: 1789-1859 City University Nicholas P. Zinos The Holmes Truth: Toward a Pragmatic, Holmes-Influenced Conceptualization of the Nature of Truth Jared Schroeder Politics and Constitutional Law: A Distinction Without a Difference Robert J. McKeever Acts of State, State Immunity, and Judicial Review in the United States Zia Akthar A Legacy Diminished: President Obama and the Courts Clodagh Harrington & Alex Waddan A Template for Enhancing the Impact of the