Trajectories of Queer Politics in Contemporary India Navaneetha Mokkil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

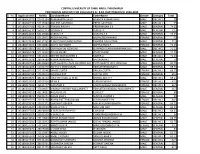

(Life Sciences) 2019-2020

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF TAMIL NADU, THIRUVARUR PROVISIONAL RANK LIST FOR Integrated M.Sc. (Life Sciences) 2019-2020 Sl. Total No. RegNo RollNo Candidate's Name Father's Name Gender Cateogry Marks 1 UI10018306 11750042 PRIYANSH CHAUDHARY NILESH CHAUDHARY MALE OBC 80 2 UI10032319 11760134 JAY VERMA PANKAJ VERMA MALE GENERAL 78.75 3 UI10008919 11590139 CHANDANA B NAIR BIJU P S FEMALE GENERAL 76.5 4 UI10017124 11600140 KARAN J GEORGE A J JOY MALE GENERAL 76.25 5 UI10001457 11240010 M M SHRIVIDHATRI M SIVARAMA KRISHNA FEMALE GENERAL 74.25 6 UI10010832 11030010 BHAVESH SUTHAR BHAGIRATH SUTHAR MALE OBC 73.5 7 UI10023562 11600988 JASEELA P SAIDALIKUTTY P FEMALE OBC 73 8 UI10012980 11990220 ASHWIN B NAIR B BIJU MALE GENERAL 73 9 UI10003184 11560116 SREDHA S SUNIL SUNIL S FEMALE OBC 72.75 10 UI10050945 11640223 SHAMIM AKHTAR MOHAMMAD PARVEZ ANWAR MALE GENERAL 72.5 11 UI10024207 11601005 BINSHAD KALLAYI ABDURAHMAN MALE OBC 71.75 12 UI10051129 11740091 RAJA BRINDHA K KRISHNAN FEMALE OBC 71.25 13 UI10058936 11730025 ANJANEYA J S JISHA E T MALE OBC 71.25 14 UI10028261 11780044 SAVIO JOHN AUGUSTINE AUGUSTHY K J MALE GENERAL 71 15 UI10010463 11990029 KARTHIK BINU KARTHIK BINU MALE GENERAL 70.75 16 UI10041232 11601286 ALKA GEORGE GEORGE JOSEPH FEMALE GENERAL 70.75 17 UI10000389 11580003 ANUBHAV JETHI ANUBHAV JETHI MALE GENERAL 70.75 18 UI10040914 11601276 MOHAMED YASEEN ABDU PALLIKKAL MALE OBC 70 19 UI10000928 11590003 ANJALI P K RAMAKRISHNAN M V FEMALE GENERAL 69.25 20 UI10061970 12070248 TRIPTI PANDEY PRADEEP KUMAR PANDEY FEMALE GENERAL 69.25 21 UI10002277 -

Malayalam - Novel

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - NOVEL SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 4000 ORU SEETHAKOODY A.A.AZIS NOVEL 4001 AADYARATHRI NASHTAPETTAVAR A.D. RAJAN NOVEL 4002 AJYA HUTHI A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4003 UPACHAPAM A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4004 ABHILASHANGELEE VIDA A.P.I. SADIQ NOVEL 4005 GREEN CARD ABRAHAM THECKEMURY NOVEL 4006 TARSANUM IRUMBU MANUSHYARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4007 TARSANUM KOLLAKKARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4008 PATHIMOONNU PRASNANGAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4009 ABC NARAHATHYAKAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4010 HARITHABHAKALKK APPURAM AKBAR KAKKATTIL NOVEL 4011 ENMAKAJE AMBIKA SUDAN MANGAD NOVEL 4012 EZHUTHATHA KADALAS AMRITA PRITAM NOVEL 4013 MARANA CERTIFICATE ANAND NOVEL 4014 AALKKOOTTAM ANAND NOVEL 4015 ABHAYARTHIKAL ANAND NOVEL 4016 MARUBHOOMIKAL UNDAKUNNATHU ANAND NOVEL 4017 MANGALAM RAHIM MUGATHALA NOVEL 4018 VARDHAKYAM ENDE DUKHAM ARAVINDAN PERAMANGALAM NOVEL 4019 CHORAKKALAM SIR ARTHAR KONAN DOYLE D.NOVEL 4020 THIRICHU VARAVU ASHTAMOORTHY NOVEL 4021 MALSARAM ASHWATHI NOVEL 4022 OTTAPETTAVARUDEY RATHRI BABU KILIROOR NOVEL 4023 THANAL BALAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4024 NINGAL ARIYUNNATHINE BALAKRISHNAN MANGAD NOVEL 4025 KADAMBARI BANABATTAN NOVEL 4026 ANANDAMADAM BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJI NOVEL 4027 MATHILUKAL VIKAM MOHAMMAD BASHEER NOVEL 4028 ATTACK BATTEN BOSE NOVEL 4029 DR.DEVIL BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4030 CHANAKYAPURI BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4031 RAKTHA RAKSHASSE BRAM STOCKER NOVEL 4032 NASHTAPETTAVARUDEY SANGAGANAM C.GOPINATH NOVEL 4033 PRAKRTHI NIYAMAM C.R.PARAMESHWARAN NOVEL 4034 CHUZHALI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4035 VERUKAL PADARUNNA VAZHIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4036 ATHIRUKAL KADAKKUNNAVAR C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4037 SAHADHARMINI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4038 KAANAL THULLIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4039 POOJYAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4040 KANGALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4041 THEVADISHI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4042 KANKALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4043 MRINALAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4044 KANNIMANGAKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4045 MALAKAMAAR CHIRAKU VEESHUMBOL C.V. -

Eigible Candidates List for Stray Vacancy Ug 2020 Bds

EIGIBLE CANDIDATES LIST FOR STRAY VACANCY UG 2020 BDS (ESI IP) Sno NEETRank Rollno AppNO Name FatherName Category Mobile Email Nationality Name 1 4684 2808109311 200410880954 HARSHA SURENDRAN SURENDRAN A BC 919496714331 [email protected] Indian 2 4967 2804015172 200410051749 SANGEERTH K SAJEEVAN SAJEEVAN A GN 919645774466 [email protected] Indian 3 7567 2807018129 200411096332 ARDRA SATHEESH SATHEESH L R EW 919400130982 ardrasatheesh2018@gmail. Indian com 4 11695 2802006264 200410117669 ABIN NIRAJ NIRAJ ABRAHAM GN 919349944361 [email protected] Indian 5 13427 2803106101 200410521386 ANASWARA P R RAJEEVKUMAR P N EW 919656635591 [email protected] Indian om 6 14021 2808207153 200410000944 ASHIKA T JAYAPALAN K T GN 919947377015 [email protected] Indian om 7 16000 2802005020 200410877179 DONY ELDHOSE ELDHOSE P A EW 919447253510 [email protected] Indian m 8 16298 2802003258 200410297048 ARCHANA S SUDHEER G NAIR GN 919745195986 [email protected] Indian 9 17455 2807001097 200410619122 GAUTHAM KRISHNA S B SURESH KUMAR GN 919847869754 [email protected] Indian 10 20949 2811207349 200410521726 SANJITHA PRINCE R K PRINCE BC 919995433824 [email protected] Indian 11 27920 3111217326 200410028009 RITIK MOTIRAMSINGH BAT MOTIRAMSINGH EW 917420831618 [email protected] Indian LAXMANSINGH BAT 12 29936 4608131039 200410415417 SNEHASIS BERA SWAPAN BERA EW 919153316151 [email protected] Indian om 13 32893 1202005771 200410406993 LAGISETTY BALA YASASWI LAGISETTY CHANDRA GN 919492406557 lagisettychandrasekhar@g -

Prominent Alumni

Just like moons and like suns, With the certainty of tides, Just like hopes springing high, Still I rise.” _ Maya Angelou The alumni of Mahatma Gandhi college has a rich legacy onto which new feathers of excellence are being added, every year. With a potential for excellence, Mahatma Gandhi college has produced some of the most revered personalities whose excellence in their respective fields is a matter of pride for the college. JUSTICE PARIPOORNAN Krishnaswami Sundara Paripoornan(1932-2016) was a justice of the Supreme court of India. He is known for his landmark judgements regarding the Devaswom boards in Kerala.He had also served as the chief Chief Justice of Patna high court. JUSTICE M.R. HARIHARAN NAIR MR Hariharan Nair served the judiciary in various positions ranging from Munsiff to District judge. He was also appointed as a judge in the high court of Kerala. He has also served as the chairman of the Kerala State Prisons Review Committee of the Govt. of Kerala during 2004-2006, Ombudsman for Local Self Govt. Institutions, Chairman of the Institutional Ethics Committees of the Sree Chithira Thirunal Institute of Medical Sciences, Trivandrum, Chairman of the University Ethics Committee of the Kerala University of Health Sciences and Chairman of the Kerala State Fishermen’s Debt Relief Commission. Dr. S. NARAYANA KALKURA Dr. S. Narayana Kalkura is the Director and Professor of Crystal Growth Centre, Anna University,Chennai.He worked as a researcher and Professor in acclaimed institutions including Anna university. He is also the -

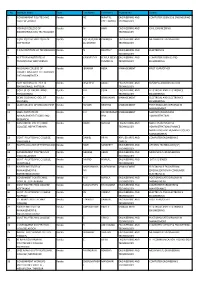

Sl. No. Applicationid Rollno Candidatename Fathername

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF TAMIL NADU, THIRUVARUR PROVISIONAL RANK LIST FOR Integrated B.Sc. B.Ed. (MATHEMATICS) 2018-2019 Sl. No. ApplicationID RollNo CandidateName FatherName Gender Cateogry Total 1 UG180041775 22102194 RAMAKANTA SAHU ANANTA KUMAR SAHU MALE OBC-NCL 79 2 UG180046739 52116340 KAILASH GADHWAL PREM GADHWAL MALE OBC-NCL 75 3 UG180007406 46114414 PRANAV RAJ M V PREMARAJAN E K MALE GENERAL 74.25 4 UG180056130 16101373 SOURAV S SURESH C MALE GENERAL 73.5 5 UG180014460 66119948 VARUN C P VIJAYAN A P MALE GENERAL 73.25 6 UG180099681 66119971 ARDRA MURALI MURALEEDHARAN D FEMALE GENERAL 73 7 UG180137036 89131265 K SANTOSH KUMAR KOTHA ESWARA RAO KOTHA MALE GENERAL 72.5 8 UG180072301 53116681 KAVYA GOPINATH GOPINATHAN P FEMALE GENERAL 72.25 9 UG180033665 89131200 DUPPADA SAI KOWSHIK DUPPADA SURYA NARAYANA LATE MALE OBC-NCL 71.25 10 UG180045578 52116339 AYUSH KHARE ANJAY KHARE MALE GENERAL 71.25 11 UG180007950 53116521 NIDHIN MOHAMMED S SAJEEB A MALE OBC-NCL 71.25 12 UG180061628 28104589 VENKATARAMAN N NAGARAJAN T MALE GENERAL 70 13 UG180130953 88130660 PUTTAGUNTA YASAS CHANDRA SAI PUTTAGUNTA JAYA PRAKASH MALE GENERAL 69.75 14 UG180126289 16101570 ADITYA V SRINIVASAN VENKATESHWARAN S MALE GENERAL 69.75 15 UG180008155 52116246 MANSI GUPTA SANJAY GUPTA FEMALE OBC-NCL 69.75 16 UG180000498 14100210 ADHISHA ROY KUNTAL ROY FEMALE GENERAL 69.5 17 UG180004920 48114534 IBRAHIM KHALEEL M M MOIDEENKUTTY MALE OBC-NCL 69.25 18 UG180023359 26103326 NEHA P SUDHAKARAN P FEMALE OBC-NCL 67.5 19 UG180027592 46114447 GAYATHRI K LOHITHAKSHAN KIZHAKKAYIL FEMALE -

Central Library Monthly Arrivals May 2015, Amritapuri Campus

Sl.NoAcc. No Title Author Subject 1 44697 A Bad Character Kapoor,Deepti English - Fiction 2 45287 A Basic Course in Real Analysis Kumar, Ajit Mathematics 3 44920 A Collection of Interesting General ChemistryElias, AnilExper J iments Chemistry 4 45293 A Complex Analysis Problem Book Alpay, Daniel Mathematics 5 44798 A Concise History of SCience in India Bose, D M Science 6 44799 A Course in Approximation Theory Light, Will Mathematics 7 45286 A Course in Mathematical Analysis Garling, D J H Mathematics 8 45285 A Couse in Mathemtaical Analysis Garling, D J H Mathematics 9 45284 A Couse in Mathemtaical Analysis Garling, D J H Mathematics 10 44762 A Dictionary of Business and ManagementOxford University Press Dictionary 11 45283 A First Course in Harmonic Analysis Deitmar, Anton Mathematics 12 44800 A Hot Story Venkataraman,G Physics 13 45012 A Introduction to the Upanishads Pruthi, Raj Kumar Spritual 14 44698 A Little Mayhem Dhar,Mainak English - Novel 15 44699 A Mid Summer Night's Dream: The New Shakespeare English - Play 16 44700 A School Counsellor's Diary Agarwala,Loya Self - Help 17 44759 A Short at History : My Obessive JourneyBindra,Abhinav to Olympic Gold Sports 18 44801 A Student's Guide to Maxwell's EquationsFleisch, Daniel Physics 19 44921 A Textbook of Organic Chemistry Bansal, Raj K Chemistry 20 44802 A Voyage Through Turbulence Physics 21 45307 A+ English Carri, E J English 22 45306 A+ English Carri, E J English 23 45002 Aaranyakam Bandyopadhyaya, Bibhoothibhoosanmalayalam - Novel 24 45001 Aarogyanikethanam Bandyopadhyaya, Tarasankarmalayalam -

Malayalam-Ug.Pdf

I Year BA/Bsc/BSW/BPA/Bsc (Fc Sc) I Semester 2016-17 I Poetry : MAGNALANA Mariyam By Vallathol Narayana Menon II Prose : Collection of Essays 1. GANDHI – KALAYUM SAHITHYAVUM KARMA YOGIYUDE KANNIL By THAYATTU SANKARA N 2. KAALIFORNIYAN SKECHUKAL By Sugatha Kumari 3. SREE NARAYANAN AAR By Sukumar Azhikodu 4. YUDDHATHINTE PARINAMAM By KuttiKrishna Marar 5. AASAN VIPLAVATHINTE SUKRANAKSHATHRAM By Joseph Mundessery III Precise Writing : No Prescribed Text Book. A passage of reasonable length should be précised, preferably on third of its length. II Semester 2016-17 I Poetry : ‘SURYAKANTHI” By G. Shankara Kurup Only the following poems should be taught 1. SURYAKANTHI 2. ENTE VELI 3. INNU NJAM, NAALE NEE 4. NISAA GEETHAM 5. PREMA PIPAASA II Prose : ’15 STORIES’ Compiled by M.V AKBAR Only the following stories are presecribed. 1. MOTHIRAM - KAAROOR NEELAKANDA PILLA. 2. ORU MANUSHYAN - BASHEER 3. RAACHIYAMMA - OROOB 4. KATTHUNNA ORU TATHA CHAKRAM - T. PADMANABHAN 5. PERUMAZHAYUDE PITTENNU - M.T VASUDEVAN NAIR III Translation : No Prescribed Text Book. An English passage of reasonable length and difficulty to be translated into malayalam. II Year BA/Bsc/BSW/BPA/Bsc (Fc Sc) III Semester 2017-18 I Poetry : Collection of Poetry 1. KOCHUTHOMMAN – ORU VIDYARTHI – PURAANAM By N.V Krishna Variar 2. MANINAADAM By Edappally Raghvan Pilla 3. MALA THURAKKAL By Vailoppilly 4. MAZHUVINTE KATHA By BAALAMANIYAMMA 5. KOTHAMPU MANIKAL By O.N.V KURUP II Prose : ‘SAAKETHAM’ (DRAMA) By C.N Sreekandan Nair III PARAAVARTHANAM : No Prescribed Text Book. A few lines of poetry, either from the prescribed text or from any other Book, to be expanded and write in proses order. -

Journal Vol 2 Issue 2

a transdisciplinary biannual research journal Vol. 2 Issue 2 July 2015 Postgraduate Department of English Manjeri, Malappuram, Kerala. www.kahmunityenglish.in/journals/singularities/ Chief Editor P. K. Babu., Ph. D Associate Professor & Head Postgraduate Dept. of English KAHM Unity Women's College, Manjeri. Members: Dr. K. K. Kunhammad, Asst. Professor, Dept. of Studies in English, Kannur University Mammad. N, Asst. Professor, Dept of English, Govt. College, Malappuram. Dr. Priya. K. Nair, Asst. Professor, Dept. of English, St. Teresa's College, Eranakulam. Aswathi. M . P., Asst. Professor, Dept of English, KAHM Unity Women's College, Manjeri. Advisory Editors: Dr. V. C. Haris School of Letters, M.G. University Kottayam Dr. M. V. Narayanan, Assoc. Professor, Dept of English, University of Calicut. Editor's Note The Singularities is into its fourth issue since it was launched in the January 2014 as a transdisciplinary biannual research Journal. The team of teachers at the English Department of KAHM Unity Women's College, Manjeri, has ensured that the Journal is issued promptly within the time frame we have set for the Journal. Not only have we stuck to the mission, but we have contributed to building writing skill and awareness to Research Writing organising workshops and training sessions in quality writing. The current issue with its core on Film, Women and Literature, carries a range of articles connecting the theme at various nodes. The surge of interest in Films and Women seems to offer a lot to complement each other. There appears to be a lot of interest in Cinema but it seems this is slow in getting translated fully into quality writing from the youngsters. -

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL)

(RJELAL) Research Journal of English Language and Literature Vol.4.Issue 3. 2016 A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal (July-Sept.) http://www.rjelal.com; Email:[email protected] RESEARCH ARTICLE GUARDIANS OF SACRED GLASS BOWL: WOMEN AND CONCEPT OF CHASTITY WITH REFERENCE TO MALAYALAM NOVELS CHEMMEEN, RATHI NIRVEDAM, SUGANDI ENNA AANDAAL DEVANAYAKI AND KHASAKKINTE ITHIHAASAM AMEERA. V.U Assistant Professor Department of English, MES Ponnani College, Ponnani, Kerala ABSTRACT Chastity and Virginity have restricted their meaning on gender basis and these words have come to be used only in relation with women. This hackneyed notion has crossed all linguistic, cultural, communal and religious boundaries and is harbored by all male dominated society. No myth is there to protect the chastity of men, only female sexuality is ‘sheltered’ by these virginity/chastity myths, definitely a construction of androcentric culture, and often powerless women become a prey to so called protectionism. Women are trained to internalize the double standard of morality for men and women by the constant interference of media, family, society, religious organizations and other all that are driven craze by this virginity fetish. Keywords Chastity Myth, patriarchy, virginity fetish ©KY PUBLICATIONS My chastity's the jewel of our house, realm. Here the study focuses on four novel classics Bequeathed down from many ancestors. of Malayalam literature which betrays this dominant William Shakespeare, All's Well That Ends male ideology. Well Chemmeen tells the story of fishermen Though the term chastity is used in relation to the community and a myth that is much prevalent sexual behavior of men and women, somehow it among them, according to which the life of husband limited its meaning in due course to the sexual is dependent on the chastity of his woman sitting at manners of women or rather became a term to home. -

Sl. No. Applicationid Rollno Candidatename Fathername

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF TAMIL NADU, THIRUVARUR PROVISIONAL RANK LIST FOR Integrated M.Sc. (PHYSICS) 2018-2019 Sl. No. ApplicationID RollNo CandidateName FatherName Gender Cateogry Total 1 UG180059355 41112014 SNEHIL KHAJURIA SATISH KHAJURIA MALE GENERAL 85 2 UG180065457 26103116 SHILPA S SASEENDRAN VP FEMALE GENERAL 83 3 UG180071898 83129112 SHIJIN P P RADHAKRISHNAN P P MALE OBC-NCL 82 4 UG180129431 37108060 YENNAM AKSHAY YENNAM VASUDEV MALE GENERAL 80.75 5 UG180071371 17101732 SAKSHI GOYAL SANJEEV GOYAL FEMALE GENERAL 80.25 6 UG180010423 28104812 S NIKHIL VISWANATH V SIVAKUMAR MALE GENERAL 79.5 7 UG180007979 53116522 BENSON VARGHESE VARGHESE S MALE GENERAL 79.25 8 UG180128370 37108055 KARTHEEK SIVAVARMA NADIMPALLI SIVARAMA RAJU NADIMPALLI MALE GENERAL 79.25 9 UG180041775 22102194 RAMAKANTA SAHU ANANTA KUMAR SAHU MALE OBC-NCL 79 10 UG180041677 89131203 PORANA RAJIV P CH SRINIVASARAO MALE OBC-NCL 79 11 UG180047552 48114701 HRUDYA LAKSHMI BOSE T P BOSE FEMALE OBC-NCL 77 12 UG180043819 26103505 MOHAMED BADUSHA SAIDALAVI C C MALE OBC-NCL 77 13 UG180089823 68120877 SHIVESH KUMAR KOHINOOR PRASAD MALE OBC-NCL 77 14 UG180014510 60118336 RADHIKA RAO VENKATESH RAO FEMALE GENERAL 76.75 15 UG180075595 37108560 DAMERLA ADITYA DAMERLA RAMA MURTHY MALE GENERAL 76.75 16 UG180080023 52116079 SRAJAN GUPTA ANJESH KUMAR GUPTA MALE GENERAL 76.25 17 UG180074193 37107883 KAVETI MARUTHI ABHIRAM KAVETI VENU MALE OBC-NCL 75.25 18 UG180071840 16101509 SWARUP PACKIRISAMY S PACKIRISAMY MALE GENERAL 75 19 UG180046739 52116340 KAILASH GADHWAL PREM GADHWAL MALE OBC-NCL -

Portrayal of Women in P. Padmarajan's Cinema

Educational Research International Vol.9(2) August-November 2020 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PORTRAYAL OF WOMEN IN P. PADMARAJAN’S CINEMA:WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO NOVEMBERINTE NASHTAM Sreedevi T. ; B. K. Ravi Department of Communication, Bangalore University, INDIA. [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Indian cinema has been considered as an intimate medium of communication. Being a strong audio-visual platform, it is a suitable canvas for storytelling to a mass audience. Malayalam cinema as a widely accepted film industry in Indian cinema claims to undergo changes since its inception subjectively and technically. P. Padmarajan a renowned Malayalam author, script writer and director had immensely contributed to Malayalam literature and cinema during the seventies and eighties. The detailing in his screenplays had enriched films as mirrors of society representing various social changes at major times. The women in Padmarajan films have always been a subject of discussion and have led to numerous critical studies. The outline of women characters in his films have always stayed ahead of those times. Hence, this study aims to do a detailed analysis of ‘Meera’, a central character of the film ‘Novemberinte Nashtam’ released in the year 1982. This -

S. No. Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme Course 1

S. No. Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme Course 1 GOVERNMENT POLYTECHNIC Kerala NC NIRAPPIL ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE & ENGINEERING COLLEGE,ADOOR CHELLAMMA TECHNOLOGY 2 YOUNUS COLLEGE OF Kerala M HARI ENGINEERING AND CIVIL ENGINEERING ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY 3 GOVT POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE Kerala KOCHUPURACK CINIMOLE ENGINEERING AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERING KOTTAYAM AL GEORGE TECHNOLOGY 4 T.K.M INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Kerala N REVATHY ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS TECHNOLOGY 5 KOTTAYAM INSTITUTE OF Kerala GANAPATHY KOKILA SELVA ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY AND SCIENCE KUMARI.G TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING 6 MUSALIAR COLLEGE OF Kerala IBRAHIM HEBA MANAGEMENT FIRST YEAR/OTHER ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY PATHANAMTHITTA 7 SREE BUDDHA COLLEGE OF Kerala RISA DEVI ANJALI ENGINEERING AND BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION ENGINEERING, PATTOOR TECHNOLOGY 8 COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING Kerala V R JISHA ENGINEERING AND ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS TRIVANDRUM TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING 9 SCMS COCHIN SCHOOL OF Kerala V. SRINIVASAN MANAGEMENT ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS BUSINESS ENGINEERING 10 LEAD COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT Kerala KUMAR KRISHNA MANAGEMENT POST GRADUATE DIPLOMA IN MANAGEMENT 11 SNES INSTITUTE OF Kerala C.K RAVINDRANAT MANAGEMENT MASTERS IN BUSINESS MANAGEMENT STUDIES AND HAN ADMINISTRATION RESEARCH 12 GOVERMENT POLYTECHNIC Kerala KNOX SMITHA ENGINEERING AND MASTERS IN BUSINESS COLLEGE, NEYYATTINKARA TECHNOLOGY ADMINISTRATION (FINANCE MARKETING AND HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT) 13 GOVT. POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE, Kerala DANIEL PRIYA