Lessons Learned While Protecting Wild Chimpanzees in West Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sapo National Park in West Africa: Liberia's First

362 Environmental Conservation Sapo National Park in West Africa: Liberia's First Sapo National Park is the first to be established of three proposed national parks and four nature reserves that were selected in late 1978 and early 1979 with the assistance of IUCN and the World Wildlife Fund. The Park is situated in southeastern Liberia and covers a total land area of 505 sq. miles (1,308 sq. km) of primary lowland rain-forest (Fig. 1). Sapo is 440 miles (704 km) by road from Monrovia, Liberia's capital city. There are regular local air services from Monrovia to Greenville (lying to the South-West of the Park) and Zwedru to its North. The new National Park supports many species of large and small mammals which are also distributed through- out the forested regions of the country. Among these are FIG. 1. Aerial view of Sapo National Park, Liberia, showing the seven species of duikers including rare ones such as undulating terrain and covering of rain-forest. Jentink's Duiker {Cephalophus jentinki), Ogilby's Duiker (C. ogilbyi), and the Zebra Duiker (C. zebra). Other others are ex-hunters or farmers who are well-acquainted mammals include the Bongo (Boccerns euryceros), Pygmy with the forest environment in that part of the country. Hippopotamus {Choeropsis liberiensis), Forest Buffalo The official establishment of Sapo National Park in {Syncerus coffer nanus), and the Forest Elephant May 1983 was a major breakthrough for wildlife {Loxodonta africana cyclotis). More than ten species of conservation practices in Liberia, and its development primates are found in Sapo: these include Chimpanzee may stimulate the creation of the other national parks and {Pan troglodytes), Western Black and White Colobus nature reserves. -

An Act for the Extension of Ti1e Sapo National Park

AN ACT FOR THE EXTENSION OF TI1E SAPO NATIONAL PARK APPROVED: OCTOBER 10,2003 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS ,OCTOBER 24, 2003 MONROVIA, LIBERIA AN ACT FOR THE EXTENSION OF THE SAPO NATIONAL PARK WHEREAS, it has been the policy of the Government of the Republic of Liberia to adopt such measures as deemed conducive in the interest of the State; and WHEREAS, our forests are among our greatest natural resources and may be made to contribute greatly to the socio economic, scientific and educational welfare of Liberia by being managed in such a manner as to ensure their sustainable use; and WHEREAS, the protection, conservation and sustainable utilization of these resources must be carried out promptly, efficiently and wisely, under such conditions as will ensure continued benefits to present and future generations of Liberia; and WHEREAS, 'Sapo National Park, establlsheo in 1983, is recognized as being at the core of an immense forests block of the Upper Guinea Forest Ecosystem that is important to the conservation of the biodiversity of Liberia and of West Africa as a whole; and WHEREAS, it has been determined by socio-economic and biological surveys and with consultation of the local community that the integrity of the Sapo National Park consisting of 323,075 acres requires that its boundaries be extended; NOW THEREFORE it is enacted by the Senate and the House at Representatives ofthe Republic ofUberia, in Legislative Assembled: Section 1.1 Title: An Act for the Extension of the Sapo National Park to Embrace 445,677 Acres of Forest Land Section 1. -

Panthera Pardus) Range Countries

Profiles for Leopard (Panthera pardus) Range Countries Supplemental Document 1 to Jacobson et al. 2016 Profiles for Leopard Range Countries TABLE OF CONTENTS African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)...................................................... 4 North Africa .................................................................................................. 5 West Africa ................................................................................................... 6 Central Africa ............................................................................................. 15 East Africa .................................................................................................. 20 Southern Africa ........................................................................................... 26 Arabian Leopard (P. p. nimr) ......................................................................... 36 Persian Leopard (P. p. saxicolor) ................................................................... 42 Indian Leopard (P. p. fusca) ........................................................................... 53 Sri Lankan Leopard (P. p. kotiya) ................................................................... 58 Indochinese Leopard (P. p. delacouri) .......................................................... 60 North Chinese Leopard (P. p. japonensis) ..................................................... 65 Amur Leopard (P. p. orientalis) ..................................................................... 67 Javan Leopard -

Rajan Amin Zsl Camera Trapping

ZSL CAMERA TRAP ANALYSIS PACKAGE RAJAN AMIN ZSL CAMERA TRAPPING • BIODIVERSITY SURVEY AND MONITORING • RESEARCH IN ANALYTICAL METHODS • TRAINING IN FIELD IMPLEMENTATION • ANALYTICAL PROCESSING TOOLS • RANGE OF SPECIES, HABITATS & CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES ZSL CAMERA TRAPPING • ALGERIA • MONGOLIA • KENYA • NEPAL • TANZANIA • THAILAND • LIBERIA • INDONESIA • GUINEA • RUSSIA • NIGER • SAUDI ARABIA • Et al. KENYA: ADERS’ DUIKER COASTAL FOREST • Critically endangered species • Poor knowledge of wildlife in the area MONGOLIA: GOBI BEAR DESERT • Highly threatened flagship species • Very little known about it NEPAL: TIGER GRASSLAND AND FORESTS • National level surveys, highly threatened flagship species SAUDI ARABIA: ARABIAN GAZELLE • Highly threatened species • Monitoring reintroduction efforts ZSL CAMERA TRAP ANALYSIS PACKAGE OCCUPANCY SPECIES RICHNESS TRAPPING RATE & LOCATION ACTIVITY Why is an analysis tool needed? MANUAL PROCESSING: MULTI-SPECIES STUDIES 45 cameras x 150days x c.30sp 30 25 20 15 Observed Discovery Rate N SpeciesN Minus 1 sd 10 Plus 1 sd Diversity estimate (Jacknife 1) 5 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Days of Camera trapping WA Large-spotted Genet Bourlon's Genet 7 8 6 7 5 6 5 4 4 3 Events Events 3 2 2 1 1 0 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 Hr. Hr. MANUAL PROCESSING: MULTI-SPECIES STUDIES 80 Camera sites x 100 days x c.30sp Amin, R., Andanje, S., Ogwonka, B., Ali A. H., Bowkett, A., Omar, M. & Wacher, T. 2014 The northern coast forests of Kenya are nationally and globally important for the conservation of Aders’ duiker Cephalophus adersi and other antelope species. -

Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK

Technical Assistance Report Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK - Sapo National Park -Vision Statement By the year 2010, a fully restored biodiversity, and well-maintained, properly managed Sapo National Park, with increased public understanding and acceptance, and improved quality of life in communities surrounding the Park. A Cooperative Accomplishment of USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon- USDA Forest Service May 29, 2005 to June 17, 2005 - 1 - USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Protected Area Development Management Plan Development Technical Assistance Report Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon 17 June 2005 Goal Provide support to the FDA, CI and FFI to review and update the Sapo NP management plan, establish a management plan template, develop a program of activities for implementing the plan, and train FDA staff in developing future management plans. Summary Week 1 – Arrived in Monrovia on 29 May and met with Forestry Development Authority (FDA) staff and our two counterpart hosts, Theo Freeman and Morris Kamara, heads of the Wildlife Conservation and Protected Area Management and Protected Area Management respectively. We decided to concentrate on the immediate implementation needs for Sapo NP rather than a revision of existing management plan. The four of us, along with Tyler Christie of Conservation International (CI), worked in the CI office on the following topics: FDA Immediate -

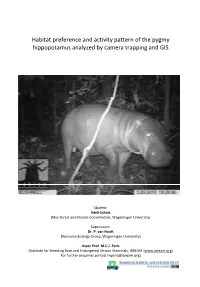

Habitat Preference and Activity Pattern of the Pygmy Hippopotamus Analyzed by Camera Trapping and GIS

Habitat preference and activity pattern of the pygmy hippopotamus analyzed by camera trapping and GIS Student: Henk Eshuis (Msc Forest and Nature Conservation, Wageningen University) Supervisors: Dr. P. van Hooft (Resource Ecology Group, Wageningen University) Assoc Prof. M.C.J. Paris (Institute for Breeding Rare and Endangered African Mammals; IBREAM (www.ibream.org) For further enquiries contact [email protected]) Habitat preference and activity pattern of the pygmy hippopotamus analyzed by camera trapping and GIS Submitted: 03-11-2011 REG-80439 Student: Henk Eshuis (Msc Forest and Nature Conservation, Wageningen University) 850406229010 Supervisors: Dr. P. van Hooft (Resource Ecology Group, Wageningen University) Assoc prof. M.C.J. Paris (Institute for Breeding Rare and Endangered African Mammals; IBREAM, www.ibream.org) Abstract The pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis) is an elusive and endangered species that only occurs in West Africa. Not much is known about the habitat preference and activity pattern of this species. We performed a camera trapping study and collected locations of pygmy hippo tracks in Taï National Park, Ivory Coast, to determine this more in detail. In total 1785 trap nights were performed with thirteen recordings of pygmy hippo on ten locations. In total 159 signs of pygmy hippo were found. We analyzed the habitat preferences with a normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) from satellite images, distance to rivers and clustering using GIS. The NDVI indicates that pygmy hippos are mostly found in a wetter vegetation type. Most tracks we found in the first 250 m from a river and the tracks show significant clustering. These observations indicate that the pygmy hippopotamus prefers relatively wet vegetation close to rivers. -

Guinean Forests of West Africa Biodiversity Hotspot Small Grants Key Information 1

Call for Letters of Inquiry (LOI) Guinean Forests of West Africa Biodiversity Hotspot Small Grants Key information 1. Eligible Countries: Benin, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, Sao Tome & Principe, Sierra Leone and Togo Deadline: August 14, 2017 Eligible Strategic Directions: 1, 2 and 3 (you must choose only one) Eligible Applicants: This call is open to community groups and associations, non-governmental organizations, private enterprises, universities, research institutes and other civil society organizations. Small Grants (up to US$50,000): Submit letters of Inquiry (LOIs) by email to [email protected]. The LOI application template for small grants can be found in English here. Table of Contents 1. Background……………………….................................................................................................2 2. Ecosystem Profile Summary………………………………………………………………………….2 3. Eligible Applicants………………………………………………………………………………………3 4. Eligible Geographies……………………………………………………………………………………3 5. Eligible Strategic Directions…………………………………………………………………………..4 6. How to Apply……………………………………………………………………………………………..5 7. Closing Date……………………………………………………………………………………………...5 8. Contacts…………………………………………………………………………………………………...6 Annex…………………………………………………………………………………………………………...7 1 1. Background The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is designed to safeguard Earth’s biologically richest and most threatened regions, known as biodiversity hotspots. CEPF is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de -

FINAL REPORT: Survey of Wildlife and Anthropogenic Threats in the Grebo-Sapo Corridor, South-Eastern Liberia

FINAL REPORT: Survey of Wildlife and Anthropogenic threats in the Grebo-Sapo Corridor, South-eastern Liberia (May-July 2015) Prepared by Wild Chimpanzee Foundation In collaboration with Forestry Development Authority, Liberia December 2015 FURNELL Simon DOWD Dervla TWEH Clement ZORO GONE BI Irie Berenger VERGNES Virginie NORMAND Emmanuelle BOESCH Christophe Wild Chimpanzee Foundation [email protected] Tel: +231(0) 880 533 495 Final Report: Survey of Wildlife and Anthropogenic threats in the Grebo-Sapo Corridor, 2014, WCF/FDA Executive summary A- Generalities and Survey Methodology In 2013, a corridor linking Proposed Grebo-Krahn National Park(PGKNP) with the Sapo National Park (SNP) was identified, under the Taï-Grebo-Sapo Transboundary Corridor Initiative, a scheme led by the Governments of Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia. The corridor runs through a major logging concession (FMC ‘F’) and community land (Putu and Chedepo Districts of Grand Gedeh and River Gee counties respectively). To evaluate the feasibility and potential impact of creating the corridor, a survey was led to measure the presence of both wildlife and anthropogenic threats inside the corridor. The survey would also provide a first idea of the potential boundary lines of the corridor. Supervised by trained WCF staff and FDA rangers, 3 teams of trained FDA rangers, auxiliaries and community members walked 103.17 km across two systematic transect designs (1 for the concession, 1 for the community land) between the 28th of May 2015 and the 15th of July 2015. Data was collected on the presence of large mammal and anthropogenic activities. Data was collected following IUCN Standards for Great Ape Surveys (Kühl et al., 2008). -

Choeropsis Liberiensis ) in and Around the Gola Rainforest National Park

Studying the distribution and abundance of the Endangered pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis ) in and around the Gola Rainforest National Park in southeastern Sierra Leone by Jerry C. Garteh A Dissertation in the Department of Biological Sciences submitted to the School of Environmental Sciences of Njala University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Award of Degree of Master of Science in Biodiversity Conservation December 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ i List of Tables ................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures ................................................................................................................ v List of Appendices ......................................................................................................... vi Abstract ......................................................................................................................... vii Dedication ..................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgement ......................................................................................................... ix Certification ................................................................................................................... xi CHAPTER ONE 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................ -

Large Mammal Rapid Biodiversity Assessment

LARGE MAMMAL RAPID BIODIVERSITY ASSESSMENT in the Wonegizi REDD+ Project Site prepared for Fauna and Flora International by ELRECO February 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A large mammal survey was carried out in Wonegizi from 21.11.-10.12.19 under FFI’s Wonegizi REDD+ Project in order to provide baseline data against which biodiversity objectives may be monitored, as well as to inform the project on the connectivity between Ziama, Wonegizi and Wologizi PPAs for large mammals to understand how such species are moving through the landscape and to provide recommendations for the establishment and management of wildlife corridors. The survey focused on 31 medium to large sized mammal species with an emphasis on indicator species of global conservation concern. A combination of data collection methods was used, including desk review, interview surveys, reconnaissance surveys, HCV-species targeted surveys, as well as Forest Elephant and Pygmy Hippo dung sample collection. Field surveys were carried out in two different study areas, one in central Wonegizi and one in the northern part of the PPA. For the corridor assessment potential sites were identified per satellite imagery and evaluated in the field through local information and ground-truthing of forest cover, connectivity, extent of human impact and forest degradation. The resident large mammal fauna of Wonegizi consists of 24 species, including the Western Chimpanzee, seven monkey species, the Forest Elephant, Pygmy Hippo, Leopard, African Golden Cat, Bongo, Bushbuck, five duiker species, the Water Chevrotain, Red River Hog, Giant Ground Pangolin, Black-bellied and White-bellied Pangolin. Another four species, i.e. the Putty-nosed Monkey, Green Monkey, Forest Buffalo and Zebra Duiker might be present as well, but uncommon, i.e. -

RSPO NOTIFICATION of PROPOSED NEW PLANTING This

RSPO NOTIFICATION OF PROPOSED NEW PLANTING This notification shall be on the RSPO website f`or 30 days as required by the RSPO procedures for new plantings (http://www.rspo.org/?q=page/53). It has also been posted on local on-site notice boards. Date of notification: Tick whichever is appropriate √ This is a completely new development and stakeholders may submit comments. This is part of an ongoing planting and is meant for notification only. Location of proposed new Tarjuowon District, Sinoe County, Republic of Liberia planting: Company Name Golden Veroleum (Liberia) Inc. Address 17th Street, Villa Samantha ( Beach Side), Sinkor, Monrovia, Liberia Phone +44 7780- 662 800 Contact David Rothschild (Director) E-mail [email protected] Contact Matt Karinen (Director) E-mail [email protected] RSPO Membership No.: 1-0102-11-000-00 Ordinary member Approved 29/08/2011, 1 Figure 1: Location Map of project Area in Tarjuowon District, Sinoe County, Republic of Liberia Figure 2: Location of the proposed Tarjuowon development area and protected areas in Liberia 2 Figure 3: Map of concession showing towns and villages and HCV set-asides in the area 3 1.0 Summary from SEI Assessments In 2010 an oil palm plantation concession agreement was signed between the Government of Liberia and GOLDEN VEROLEUM (LIBERIA) covering five (5) counties in Liberia: Grand Kru, Sinoe, Maryland, Rivercess and Grand Kru for a period of 65 years with an option for renewal. This agreement covers a total of approximately 500,000 acres (220,000 hectares). The concession agreement amongst other things provides for the implementation of a social and community development program, which includes the creation of about 35,000 jobs in 5 counties within a 15 year period, construction of employee housing, education, medical care, a Liberian smallholder program and the construction of about 16 mills and 2 sea ports within 15 years. -

Poaching Empties Critical Central African Wilderness of Forest Elephants

Current Biology Magazine Correspondence A 40 Poaching empties critical Central 30 African wilderness 20 of forest elephants John R. Poulsen1,2,*, Sally E. Koerner1,3, 10 Sarah Moore1, Vincent P. Medjibe1,2, 4 1,2 Stephen Blake , Connie J. Clark , Number of elephants (in thousands) 0 Mark Ella Akou5, Michael Fay2, 2004 2014 Amelia Meier1, Joseph Okouyi2,6, Years Cooper Rosin1, and Lee J. T. White2,6,7 B 2.0 Elephant populations are in peril everywhere, but forest elephants in Survey 2004 2014 Central Africa have sustained alarming 1.5 losses in the last decade [1]. Large, remote protected areas are thought 1.0 Density to best safeguard forest elephants by supporting large populations buffered 0.5 from habitat fragmentation, edge effects and human pressures. One such area, the Minkébé National Park 00 (MNP), Gabon, was created chiefl y 0 2 4 6 8 Elephant density, km-2 for its reputation of harboring a large C elephant population. MNP held the Cameroon highest densities of elephants in Central Africa at the turn of the century, and was considered a critical sanctuary for forest elephants because of its relatively large size and isolation. We assessed Republic population change in the park and of the congo its surroundings between 2004 and Dung abundance 2014. Using two independent modeling 20 approaches, we estimated a 78–81% 0 decline in elephant numbers over ten Transect National park years — a loss of more than 25,000 Major road elephants. While poaching occurs from 50 km within Gabon, cross-border poaching largely drove the precipitous drop in elephant numbers.