UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title Robert B. Stevens: UCSC Chancellorship, 1987-1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/95h8k9w0 Authors Stevens, Robert Jarrell, Randall Regional History Project, UCSC Library Publication Date 1999-05-21 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/95h8k9w0#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction The Regional History Project conducted six interviews with UCSC Chancellor Robert B. Stevens during June and July, 1991, as part of its University History series. Stevens was appointed the campus’s fifth chancellor by UC President David P. Gardner in July, 1987, and served until July, 1991. He was the second UCSC chancellor (following Chancellor Emeritus Robert L. Sinsheimer) recruited from a private institution. Stevens was born in England in 1933 and first came to the United States when he was 23. He was educated at Oxford University (B.A., M.A., B.C.L., and D.C.L.) and at Yale University (L.L.M.) and became an American citizen in 1971. An English barrister, Stevens has strong research interests in legal history and education in the United States and England. He served as chairman of the Research Advisory Committee of the American Bar Foundation, has written a half dozen books on legal history and social legislation, and numerous papers on American legal scholarship and comparative Anglo-American legal history. Prior to his appointment at UCSC he served for almost a decade as president of Haverford College from 1978 until 1987. From 1959 to 1976 he was a professor of law at Yale University. -

Visionaries of the Visual

UC SANTA CRUZ Winter 2001 R E V I E W Visionaries ofthe Visual Ada Takahashi is one of the many UCSC alumni working as museum and gallery curators and directors Plus: Filling the teacher gap; Measuring mercury contamination CONTENTS FROM THE CHANCELLOR By M.R.C. Greenwood UC Santa Cruz Features Visionaries of the visual n my position as chancellor, challenge, launching a 15-month Review As curators or directors at I am fortunate indeed to come in program that provides our students Chancellor some of the country’s most contact with many of the people with both a teaching credential and M.R.C. Greenwood Visionaries of the Visual 8 respected art museums that make the UC Santa Cruz master’s degree in education. and galleries, a number of II Vice Chancellor, University Relations community so special: our students, Our faculty and students are Ronald P. Suduiko UCSC graduates are helping whose thirst for knowledge is only achieving distinction in a variety of decide which works their Associate Vice Chancellor, Meeting the Need 14 exceeded by their commitment to other ways. Research that is revealing Communications institutions buy or borrow— improve society; our faculty and staff, important information about mercury Elizabeth Irwin and ultimately bring to who diligently see to it that our students contamination in San Francisco Bay Editor freidman/losgary angeles times the public’s attention. 8 receive a world-class education at the waters is one example of that excel- Mercury: A Toxic Legacy 18 Jim Burns Meeting the need same time that UCSC produces impres- lence (page 18). -

The UC Santa Cruz Budget – a Bird's Eye View

Office of Planning and Budget 2012-13 Edition The UC Santa Cruz Budget – A Bird’s Eye View Message from Office of Planning and Budget… December 2012 On behalf of the staff in Planning and Budget, I am happy to provide you with the 2012-13 edition of The Those birds have a good view of the budget. Birds Eye View. This document provides a unique look at the permanent operating budget for the campus and each of its major units. It includes recent data on the degrees conferred, the majors of our students, the number of faculty budgeted in each department, enrollments by department, and extramural awards. You can find it on the web at http://planning.ucsc.edu/budget/reports/birdseye. UCSC has implemented cuts in each of the past five years. While the cuts have been primarily in the core-funded areas, the impact has been felt throughout the campus. The passage of Proposition 30—and steps taken by the UC Office of the President to renew discussions with the State concerning the longer term funding needs of the University—represents the prospect for California to put public higher education back on a pathway toward fiscal stability. If the State and the UC Regents each agree on a multi-year financial plan for UC, this will create an opportunity for UCSC to create our own multi-year path. While additional cuts will be needed in 2013-14 to address the budget shortfall from 2012-13, we are cautiously optimistic that we can begin to plan for more budget stability. -

UA 128 Inventory Photographer Neg Slide Cs Series 8 16

Inventory: UA 128, Public Information Office Records: Photographs. Photographer negatives, slides, contact sheets, 1980-2005 Format(s): negs, slides, transparencies (trn), contact sheets Box Binder Title/Description Date Photographer (cs) 39 1 Campus, faculty and students. Marketing firm: Barton and Gillet. 1980 Robert Llewellyn negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Paul Schraub negatives, cs 39 2 Set construction; untitled Porter sculpture (aka"Wave"); computer lab; "Flying Weenies"poster 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Tennis, fencing; classroom 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Bike path; computers; costumes; sound system; 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Admissions special programs (2 pages) 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown family housing 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Student family apartments 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown Santa Cruz 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Special Collections, UCSC Library 1984 Lucas Stang negatives, cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Childcare center 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 East Field House; Crown College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Performing Arts; Oakes; Porter sculpture (The Wave) 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs Jack Schaar, professor of politics; Elena Baskin Visual Arts, printmaking studio; undergrad 39 3 chemistry; Computer engineering lab -

COLLEGE EIGHT FROSH WELCOME to UCSC Welcome to UC Santa Cruz and Congratulations! This Is a Very Exciting Time in Your Life As You Begin a New Phase of Learning

ENVIRONMENT SOCIETY COLLEGE EIGHT FROSH Welcome Week Guide 2014 Week Welcome COLLEGE EIGHT WELCOME TO UCSC Welcome to UC Santa Cruz and congratulations! This is a very exciting time in your life as you begin a new phase of learning. Every year students tell us that a key factor to their success is getting involved on campus and making a difference in their community. We hope you take advantage of this week to learn as much as possible about your new environment. Fall Welcome Week has been planned for you to learn about the academic resources, to become familiar with the campus, and to learn about the Santa Cruz community. Use this guide to learn about the many workshops/events taking place campus-wide during Fall Welcome Week. Notice that some events are MANDATORY. Your academic and social transition to UC Santa Cruz is extremely important to us. We consider you a partner in your academic and social success here. Therefore we expect you to actively participate in the many programs and services this first week and well beyond. So, start now and begin making connections! 1 WELCOME TO COLLEGE EIGHT Welcome to College Eight and UC Santa Cruz! There are a number of things you’ll need to accomplish during your first several days on campus. This Orientation Schedule is designed to help guide you. Use it to learn about the many workshops, orientations, office hours and events across campus during Welcome Week. If you need more information ask an Orientation Leader (OL), Programs Assistant (PA), Resident Assistant (RA) or a member of our college staff. -

Inauguration of George Blumenthal Set for June 6 Tablished Jean H

Botanist’s $350,000 gift establishes endowed chair Dinner raises funds for students in need Ca m p u s update C Santa Cruz has appoint- cludes investigations of invasive Ued Ingrid Parker, associate plant species and the evolution- matt fitt matt professor of ecology and evolu- ary interactions of plants and tionary biology, to the newly es- plant pathogens. Inauguration of George Blumenthal set for June 6 tablished Jean H. Langenheim “It is such an honor to be eorge Blumenthal, culture of excellence, inquiry, Endowed Chair in Plant associated with Jean, who is a a professor of astronomy creativity, diversity, and public Ecology and Evolution. Parker real pioneer in plant ecology G is the first faculty and astrophysics at UCSC service while developing solu- member to hold the since 1972, was named tions to the world’s most criti- endowed chair, es- tim stephens permanent chancellor cal challenges.” He pledged to tablished by a gift September 19, 2007, after work with staff, alumni, com- of $350,000 from serving as acting chancellor munity members, government Langenheim, profes- for 14 months. In his first officials, and campus sup- sor emerita of ecolo- gy and evolutionary address to the campus after porters to “accelerate UCSC’s Alumna and scholarship recipient Precious Ward (above) spoke biology. being appointed by the upward trajectory.” at UCSC’s Scholarship Benefit Dinner on February 9 about the The endowment UC Regents, he pledged to In a recent interview,* important role individual contributions play in the education of provides funds to “plan strategically and act Blumenthal recalled coming UCSC students. -

2020-21 DOMESTIC EXCHANGE PROGRAM APPLICATION Note: the Last Day to Submit This Application to the Office of the Registrar Is Feb

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR Registrar, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Phone (831) 459-4412 • FAX (831) 459-5051 [email protected] 2020-21 DOMESTIC EXCHANGE PROGRAM APPLICATION Note: The last day to submit this application to the Office of the Registrar is Feb. 22, 2020. After Feb. 22, 2020, contact [email protected] for assistance. For more information, see the Domestic Exchange Programs webpage. REQUESTOR Name (Last, First, Middle) _____________________________________________________________________________ Student ID __________________________________________ Birthdate ______________________________________ College ___________________________________________ Major ___________________________________________ Total credits (including this quarter) _____________________ ACADEMIC LEVEL Frosh Sophomore Junior Senior FINANCIAL AID I expect to receive UCSC financial aid during the exchange period. Yes No PREFERENCES University University of New Hampshire University of New Mexico Period 202020-21 Academic Year 202020 Fall Semester Only 202021 Spring Semester Only Please complete page 2 and the Proposed Course Study Plan beginning on page 3. Page 1 of 5 Revised: 11/27/2019 DIVISION OF UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION Rachel Carson College • Cowell College • Crown College • Kresge College • Merrill College • Oakes College • Porter College • Stevenson College Campus Orientation • Enrollment Management • Financial Aid and Scholarships • Office of the Registrar • Undergraduate Admissions Campus Advising Coordination • Educational Partnership Center • Office of the Vice Provost and Dean • Summer Session UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR Registrar, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Phone (831) 459-4412 • FAX (831) 459-5051 [email protected] 2020-21 DOMESTIC EXCHANGE PROGRAM APPLICATION Note: The last day to submit this application to the Office of the Registrar is Feb. 22, 2020. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Introduction i Early History 1 Studying Chemistry at Rutgers University 3 Graduate Studies and Political Activism at Cornell University 6 Postdoctoral Work at Harvard University 10 Applying to UC Santa Cruz 11 Arriving at UC Santa Cruz in 1971 14 Chemistry Board of Studies 16 The Early Years of Kresge College 18 Transferring to Oakes College 25 Chancellor Robert Sinsheimer 28 Chair of the Chemistry Department at UC Santa Cruz, 1985‐1988 32 Chancellor Robert Stevens 34 The Loma Prieta Earthquake of 1989 36 Chair of the Academic Senate, 1988‐1990 37 Dean of Natural Sciences, 1990‐2005 40 Planning an Engineering School 47 Other Accomplishments as Dean 51 Campus Provost/Executive Vice Chancellor, 2005‐2010 56 Campus Provost and Executive Vice Chancellor, David Kliger page 1 Establishing Six Priorities for the CP/EVC 57 The Long Range Development Plan of 2005 62 Working with Chancellor Denice Denton 63 Student Protests during the UC Regents’ Meeting at UCSC in 2006 66 Campus Academic Plan 67 Budget Crisis 74 Delivering the Bad News: The Challenges of Being CP/EVC 76 Key Colleagues 78 Chancellor George Blumenthal 81 UCSC’s Silicon Valley Research Efforts 82 Chancellor MRC Greenwood 85 Rebenching 86 More on Student Protests 90 Reflections on Serving as CP/EVC 99 Reflections on UC Santa Cruz 103 The Kliger Research Group 107 Early History Reti: Today is April 25, 2011, and this is Irene Reti of the Regional History Project at the library. I’m here with David Kliger, retired CP/EVC, and we’re going to start Dave’s oral history today. -

College Eight Environment Society

ENVIRONMENT SOCIETY Welcome Week Guide 2013 Week Welcome COLLEGE EIGHT COLLEGE EIGHT WELCOME TO UCSC WELCOME TO COLLEGE EIGHT Welcome and Congratulations! This is a very exciting time in your life Welcome to College Eight and UC Santa Cruz! as you begin your new journey learning more about yourself and the There are a number of things you’ll need to accomplish during your first world around you. Every year students tell us that a key factor to their several days on campus. This Welcome Week Schedule is designed to success is getting involved on campus and making a difference in their help guide you. Use it to learn about the many workshops, orientations, community. We expect you to take advantage of this week to learn as office hours and events across campus during Welcome Week. If much as possible about your new environment. you need more information ask an Orientation Leader (OL), Resident Assistant (RA), Programs Assistant (PA) or a member of our college Fall Welcome Week has been planned for you to learn about the staff. We’re excited to have you here in your new home! academic resources available, to become familiar with the campus, and For More College Eight Information to learn about the Santa Cruz community. Use this guide to learn about In Person the many workshops/events taking place campus-wide during Fall Student Life Office Welcome Week. Room 204 Student Commons Building Website Notice that some academic and college workshops are MANDATORY eight.ucsc.edu/activities Facebook Your academic and social transition to UC Santa Cruz is extremely facebook.com/UCSCCollege8StudentLifePrograms important to us. -

UCSC's 40Th Anniversary

UCUCREVIEW SANTASANTA CRUZCRUZFall 2005 UCSC’s 40th Anniversary: Also in this Issue: Chancellor Denton’s Investiture How today’s students are preparing Lost History to make a world of difference Hot Tech Memories of War ...and more UC SANTA CRUZ REVIEW UC Santa Cruz 40 Years of Review 8 Excellence jim mackenzie Chancellor In this anniversary year, actress Denice D. Denton Elise Youssef is one of five Vice Chancellors, University Relations students profiled whose achieve- Elizabeth Irwin (Interim) ments are cause for celebration. Thomas Vani (Interim) Associate Vice Chancellor, Communications Elizabeth Irwin Lost History Editor 14 Community studies professor jim mackenzie Jim Burns Paul Ortiz tells the little-known Art Director but powerful story of black Jim MacKenzie resistence to white supremacy Associate Editors Mary Ann Dewey in post-Reconstruction Florida. Jeanne Lance Writers Louise Gilmore Donahue Hot Tech Ann M. Gibb 16 Graduate student Javad Shabani jim mackenzie Jennifer McNulty Scott Rappaport is part of a team engineering Doreen Schack new technologies that could Adilah Barnes (Cowell ’72) and Paul Mixon (Stevenson ’71) attended Tim Stephens convert heat—often wasted— the 2005 African American Alumni Reunion—one of 37 reunion Cover Photography into electricity. events that took place during Banana Slug Spring Fair 2005. r. r. jones Office of University Relations Carriage House Memories University of California Your Reunion is April 22. Be there. 1156 High Street 18 of War jim mackenzie Santa Cruz, CA 95064-1077 Historian Alice Yang Murray Voice: 831.459.2501 Come to Banana Slug Spring Fair 2006 Go to alumni.ucsc.edu/reunions to: Fax: 831.459.5795 coteaches a course that considers R The All-Alumni Reunion Luncheon, with special recogni- R Reconnect with your E-mail: [email protected] how perceptions of World Web: review.ucsc.edu tion for 1971, 1976, 1981, 1986, 1991, 1996, and 2001 grads classmates online War II have changed over time. -

Printable Fall 2011 Schedule of Classes

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to the Schedule Keep Records ............................................................................... 1 Keep Records! Table of Contents ........................................................................ 1 Online Resources ......................................................................... 1 In order to fulfill your responsibility for planning your edu- Calendar Information cation, you should keep an up-to-date academic portfolio Academic and Administrative Calendar 2011–12 ..................... 2–3 containing the following kinds of information: Key Dates for Undergraduate Registration and Enrollment .......... 4 • transcripts from all schools attended; Registration • test results from entrance exams, language exams, Breakdown of Registration Fees.................................................... 4 placement exams, and advanced placement; Registration Payment Information ............................................... 5 • copies of communications to and from the university; Schedule Planner • contact information for your advisers and faculty Schedule Planner ......................................................................... 6 members; • statements of account showing registration, housing, Enrollment Information and other charges and payments. General Enrollment Information ............................................. 7–8 Graduate, Undergraduate Enrollment Appointment Schedule 9-10 You are responsible for responding to all communications Placement Exams ...................................................................... -

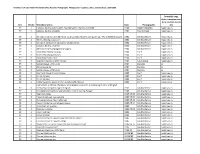

UA 50 UCSC Photography Services Inventory For

UA 50 UCSC Photography Services - Photographic Materials Job Number Date Description Negatives Contact Sheets Prints Photographer 18 1965 Long Range Development Plan (LRDP) Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 20 1965 College III (Crown College) renderings of residence halls. Box 1: partial Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 24 1965 Library - renderings of University Library: 45-12; architectural plans of University Library Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 27 1965 Campus buildings, forest Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 30 12/1/1965 Field house, interior Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 34 1966 Central Services Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 37 1966 Sorensen Portrait Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 40 1966 Madrigal singers, student musicians Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 45 1966 Graduate students, scientific equipment Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 47 1966 Jasper Rose, professor of art history, provost of Cowell College Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 50 1966 Kenneth V. Thimann, professor of biology, provost of Crown College Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 54 1966 Audiovisual staff Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 58 1966 Faculty lounge Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 61 1966 Construction progress, Stevenson College Box 1 Box 16, binder 1 no prints Al Lowry, probably 65 1966 Security, fingerprints,