Separation of Willow Tit and Marsh Tit in Britain: a Review Richard K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phenotypic Flexibility in Passerine Birds Seasonal Variation of Aerobic

Journal of Thermal Biology 36 (2011) 430–436 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Thermal Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jtherbio Phenotypic flexibility in passerine birds: Seasonal variation of aerobic enzyme activities in skeletal muscle Eric T. Liknes 1, David L. Swanson n Department of Biology, University of South Dakota, 414 E. Clark St., Vermillion, SD 57069, USA article info abstract Article history: Improved winter cold tolerance is widespread among small passerines resident in cold climates and is Received 1 March 2011 generally associated with elevated summit metabolic rate (Msum ¼maximum thermoregulatory metabolic Accepted 26 July 2011 rate) and improved shivering endurance with increased reliance on lipids as fuel. Elevated Msum and Available online 2 August 2011 improved cold tolerance may result from greater metabolic intensity, due to mass-specific increase in Keywords: oxidative enzyme capacity, or increase in the masses of thermogenic tissues. To examine the mechanisms Phenotypic flexibility underlying winter increases in Msum, we investigated seasonal changes in mass-specific and total activities Seasonal acclimatization of the key aerobic enzymes citrate synthase (CS) and b-hydroxyacyl CoA-dehydrogenase (HOAD) in Citrate synthase pectoralis, supracoracoideus and mixed leg muscles of three resident passerine species, black-capped b-Hydroxyacyl CoA-dehydrogenase chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), house sparrow (Passer domesticus), and white-breasted nuthatch Poecile atricapillus (Sitta carolinensis). Activities of CS were generally higher in winter than in summer muscles for chickadees Passer domesticus Sitta carolinensis and house sparrows, but not nuthatches. Mass-specific HOAD activity was significantly elevated in winter relative to summer in all muscles for chickadees, but did not vary significantly with season for sparrows or nuthatches, except for sparrow leg muscle. -

Discrimination of Black-Capped Chickadee (Poecile Atricapillus) Chick-A-Dee Calls Produced Across Seasons

ABC 2020, 7(2):247-256 Animal Behavior and Cognition DOI: https://doi.org/10.26451/abc.07.02.14.2020 ©Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) Discrimination of black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) chick-a-dee calls produced across seasons Erin N. Scully1, Kimberly A. Campbell2, Jenna V. Congdon1, and Christopher B. Sturdy*,1,2 1Department of Psychologya, University of Alberta 2Neuroscience and Mental Health Instituteb, University of Alberta *Corresponding author (Email: [email protected]) Citation – Scully, E. N., Campbell, K. A., Congdon, J. V., & Sturdy, C. B. (2020). Discrimination of black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) chick-a-dee calls produced across seasons. Animal Behavior and Cognition, 7(2), 247-256. doi: https://doi.org/10.26451/abc.07.02.14.2020 Abstract – While black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) primarily produce fee-bee songs in spring, they produce chick-a-dee calls year-round with call production peaking in the fall. This call serves multiple functions, including food location, flock communication, and predator alarm. As seasons change, the meaning of the call may also change. For instance, flock communication could be more important in the fall than in the spring, and food type and availability change according to season. To determine if the chick-a-dee call varies acoustically across seasons in a predictable manner, we conducted an operant go/no-go discrimination task that examined black-capped chickadees’ ability to categorize calls produced in two different seasons: fall and spring. We found that birds trained to respond to vocalizations produced in either fall or spring learned to discriminate at the same rate as birds trained to respond to pseudorandomized stimuli, suggesting that none of the groups demonstrated category learning, relying instead on rote memorization. -

Programs and Field Trips

CONTENTS Welcome from Kathy Martin, NAOC-V Conference Chair ………………………….………………..…...…..………………..….…… 2 Conference Organizers & Committees …………………………………………………………………..…...…………..……………….. 3 - 6 NAOC-V General Information ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..………….. 6 - 11 Registration & Information .. Council & Business Meetings ……………………………………….……………………..……….………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………………………..…..……...….. 11 6 Workshops ……………………….………….……...………………………………………………………………………………..………..………... 12 Symposia ………………………………….……...……………………………………………………………………………………………………..... 13 Abstracts – Online login information …………………………..……...………….………………………………………….……..……... 13 Presentation Guidelines for Oral and Poster Presentations …...………...………………………………………...……….…... 14 Instructions for Session Chairs .. 15 Additional Social & Special Events…………… ……………………………..………………….………...………………………...…………………………………………………..…………………………………………………….……….……... 15 Student Travel Awards …………………………………………..………...……………….………………………………..…...………... 18 - 20 Postdoctoral Travel Awardees …………………………………..………...………………………………..……………………….………... 20 Student Presentation Award Information ……………………...………...……………………………………..……………………..... 20 Function Schedule …………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………..…………. 22 – 26 Sunday, 12 August Tuesday, 14 August .. .. .. 22 Wednesday, 15 August– ………………………………...…… ………………………………………… ……………..... Thursday, 16 August ……………………………………….…………..………………………………………………………………… …... 23 Friday, 17 August ………………………………………….…………...………………………………………………………………………..... 24 Saturday, -

Does Predation Maintain Tit Community Diversity?

OIKOS 89: 41–45. Copenhagen 2000 Does predation maintain tit community diversity? Cecilia Kullberg and Jan Ekman Kullberg, C. and Ekman, J. 2000. Does predation maintain tit community diversity? – Oikos 89: 41–45. European tits of the genus Parus constitute a complex group of coexisting boreal birds. Here we present a survey of the distribution of three coniferous-living Parus species and one of their main predators, the pygmy owl (Glaucidium passerinum), on nine isolated islands in Scandinavia. On all islands the coal tit (Parus ater) is the sole tit species when the pygmy owl is absent. The two larger species, the willow tit (P. montanus) and the crested tit (P. cristatus), only coexist with the coal tit when pygmy owls are present. We suggest that the coexistence of willow tits, crested tits and coal tits is the result of a combination of competition for food and predator-safe foraging sites. The smaller coal tit is superior in exploitation competition for food, while the two larger species have an advantage in interference competition for predator-safe foraging sites. The association between the distribution of the pygmy owl and the two larger tit species on isolated islands in Scandinavia is consistent with the idea that the pygmy owl is a keystone predator. C. Kullberg, Dept of Zoology, Stockholm Uni6., SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden ([email protected]).–J. Ekman, E6olutionary Biology Centre, Population Biol- ogy, Uppsala Uni6., Norby6a¨gen 18D, SE-752 36 Uppsala, Sweden. Coexisting congeners usually differ in morphology and congeneric species that coexist without habitat separa- resource use. -

Black-Capped Chickadee (Poecile Atricapilla) Alec Lindsay

Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapilla) Alec Lindsay Lake Erie Metropark, Wayne Co., MI 10/30/2008 © Jerry Jourdan This species is sponsored by: Petoskey Regional Audubon Society (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) Ubiquitous, social, and tolerant of human Province of Ontario. Their southern range extends only partially across Illinois, Indiana activities, Black-capped Chickadees are and Ohio, where the Carolina Chickadee arguably among Michigan’s most easily becomes more common. recognized birds. Year-round residents of urban, rural and wilderness habitats, Black-capped Distribution chickadees are also regular visitors to bird Some of the earliest accounts of chickadees in feeders. Unlike many other “feeder birds,” Michigan (Barrows 1912) indicate chickadees chickadees are a scatter-hoarding species, have been breeding across both peninsulas of storing individual food items in thousands of the state for a long period. Black-capped caches that they remember and return to over Chickadee distribution changed slightly between long periods of time (Hitchcock and Sherry the two Atlas periods. Chickadees were reported 1990). For a small bodied bird like a chickadee, from over 3,700 Atlas blocks during MBBA II, supplemental feeding can have positive impacts compared with over 4,100 blocks in MBBA I. on winter survival (Wilson 2001). Chickadees Reports of chickadees were clearly widespread typically spend the fall and winter months in across the state, yet fewer than a quarter of larger chickadee flocks with linear dominance reports were confirmed breeding records. With hierarchies, where males dominate females and the exception of Lenawee and Hillsdale older birds dominate new recruits (Glase 1973). -

Ecology and Behaviour of Winter Floaters in a Subalpine Population of Willow Tits, Poecile Montanus

Ornis Fennica 91:29–38. 2014 Ecology and behaviour of winter floaters in a subalpine population of Willow Tits, Poecile montanus Olav Hogstad Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Section of Natural History, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Received 2. May 2013, accepted 10. October 2013 Willow Tits Poecile montanus maintain yearlong territories defended by a male and fe- male mated pair. Outside the breeding season the adult pair lives together with two to four unrelated first-year Willow Tits that have settled after a post-natal dispersal. Because the habitat of the species is largely saturated with dominant territory owners and the flock size is limited, many juveniles fail to become resident flock members. These non-territorial birds behave as migrants during autumn or stay in the area for a short time (transients) or live as floaters that switch among flocks or roam about singly. The floaters (51 colour- ringed) and transients (450 colour-ringed) did not differ physically or in their foraging be- haviour, whereas birds of these groups were more vigilant and used less time for foraging than residents (114 colour-ringed). Floaters were socially dominated by residents and also maintained a poorer nutritional status. The mean wing length of males observed for the last time in November was significantly longer than that of those seen for the last time in September or October, whereas no such differences were found for body mass or nutri- tional status. The floaters moved around solitarily and crossed several Willow Tit territo- ries (males 2–8 territories, females 2–5 territories; mean territory size ca 25 ha). -

Habitat Modelling and the Ecology of the Marsh Tit (Poecile Palustris)

HABITAT MODELLING AND THE ECOLOGY OF THE MARSH TIT (POECILE PALUSTRIS) RICHARD K BROUGHTON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2012 Bournemouth University in collaboration with the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Richard K Broughton Habitat modelling and the ecology of the Marsh Tit (Poecile palustris) Among British birds, a number of woodland specialists have undergone a serious population decline in recent decades, for reasons that are poorly understood. The Marsh Tit is one such species, experiencing a 71% decline in abundance between 1967 and 2009, and a 17% range contraction between 1968 and 1991. The factors driving this decline are uncertain, but hypotheses include a reduction in breeding success and annual survival, increased inter-specific competition, and deteriorating habitat quality. Despite recent work investigating some of these elements, knowledge of the Marsh Tit’s behaviour, landscape ecology and habitat selection remains incomplete, limiting the understanding of the species’ decline. This thesis provides additional key information on the ecology of the Marsh Tit with which to test and review leading hypotheses for the species’ decline. Using novel analytical methods, comprehensive high-resolution models of woodland habitat derived from airborne remote sensing were combined with extensive datasets of Marsh Tit territory and nest-site locations to describe habitat selection in unprecedented detail. -

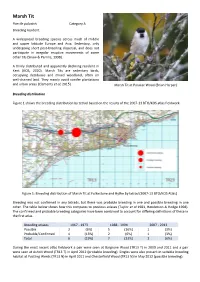

Marsh Tit Poecile Palustris Category a Breeding Resident

Marsh Tit Poecile palustris Category A Breeding resident. A widespread breeding species across much of middle and upper latitude Europe and Asia. Sedentary, only undergoing short post-breeding dispersal, and does not participate in irregular eruptive movements of some other tits (Snow & Perrins, 1998). A thinly distributed and apparently declining resident in Kent (KOS, 2020). Marsh Tits are sedentary birds, occupying deciduous and mixed woodland, often on well-drained land. They mainly avoid conifer plantations and urban areas (Clements et al, 2015). Marsh Tit at Paraker Wood (Brian Harper) Breeding distribution Figure 1 shows the breeding distribution by tetrad based on the results of the 2007-13 BTO/KOS atlas fieldwork. Figure 1: Breeding distribution of Marsh Tit at Folkestone and Hythe by tetrad (2007-13 BTO/KOS Atlas) Breeding was not confirmed in any tetrads, but there was probable breeding in one and possible breeding in one other. The table below shows how this compares to previous atlases (Taylor et al 1981, Henderson & Hodge 1998). The confirmed and probable breeding categories have been combined to account for differing definitions of these in the first atlas. Breeding atlases 1967 - 1973 1988 - 1994 2007 - 2013 Possible 2 (6%) 5 (16%) 1 (3%) Probable/Confirmed 4 (13%) 2 (6%) 1 (3%) Total 6 (19%) 7 (23%) 2 (6%) During the most recent atlas fieldwork a pair were seen at Bargrove Wood (TR13 T) in 2009 and 2011 and a pair were seen at Asholt Wood (TR13 T) in April 2012 (probable breeding). Singles were also present in suitable breeding habitat at Postling Wents (TR13 N) in April 2011 and Chesterfield Wood (TR13 N) in May 2012 (possible breeding). -

The PDF, Here, Is a Full List of All Mentioned

FAUNA Vernacular Name FAUNA Scientific Name Read more a European Hoverfly Pocota personata https://www.naturespot.org.uk/species/pocota-personata a small black wasp Stigmus pendulus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/crabronidae/pemphredoninae/stigmus-pendulus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius concinnus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-concinnus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius nigerrimus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-nigerrimus Adder Vipera berus https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/animals/reptiles-and-amphibians/adder/ Alga Cladophora glomerata https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cladophora Alga Closterium acerosum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=x44d373af81fe4f72 Alga Closterium ehrenbergii https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28183 Alga Closterium moniliferum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28227&sk=0&from=results Alga Coelastrum microporum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27402 Alga Cosmarium botrytis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28326 Alga Lemanea fluviatilis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=32651&sk=0&from=results Alga Pediastrum boryanum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27507 Alga Stigeoclonium tenue https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=60904 Alga Ulothrix zonata https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=562 Algae Synedra tenera https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=34482 -

Comparative Analysis of Hissing Calls in Five Tit Species Li Zhang, Jianping Liu, Zezhong Gao, Lei Zhang, Dongmei Wan, Wei Liang, Anders Pape Møller

Comparative analysis of hissing calls in five tit species Li Zhang, Jianping Liu, Zezhong Gao, Lei Zhang, Dongmei Wan, Wei Liang, Anders Pape Møller To cite this version: Li Zhang, Jianping Liu, Zezhong Gao, Lei Zhang, Dongmei Wan, et al.. Comparative analysis of hissing calls in five tit species. Behavioural Processes, Elsevier, 2019. hal-03024634 HAL Id: hal-03024634 https://hal-cnrs.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03024634 Submitted on 25 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Comparative analysis of hissing calls in five tit species 1 2 1 1 1, * 2 Li Zhang , Jianping Liu , Zezhong Gao , Lei Zhang , Dongmei Wan , Wei 2, * 3 3 Liang , Anders Pape Møller 1 4 Key Laboratory of Animal Resource and Epidemic Disease Prevention, 5 College of Life Sciences, Liaoning University, Shenyang 110036, China 2 6 Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Ecology of Tropical Islands, 7 College of Life Sciences, Hainan Normal University, Haikou 571158, China 3 8 Ecologie Systématique Evolution, Université Paris-Sud, CNRS, 9 AgroParisTech, Université Paris-Saclay, F-91405 Orsay Cedex, France 10 Email address: 11 LZ, [email protected], ID: 0000-0003-1224-7855 12 JL, [email protected], ID: 0000-0001-6526-8831 13 ZG, [email protected] 14 LZ, [email protected], ID: 0000-0003-2328-1194 15 DW, [email protected], ID: 0000-0002-1465-6110 16 WL, [email protected], ID: 0000-0002-0004-9707 17 APM, [email protected], ID: 0000-0003-3739-4675 18 Word count: 4571 19 *Corresponding author. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Westenhanger Area and Kiln Wood)

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 I (Westenhanger area and Kiln Wood) One of the more interesting habitats in TR13 I is the lake at Folkestone Racecourse, which holds breeding Tufted Duck, Little Grebe, Great Crested Grebe and Coot, with these being joined by Gadwall and Pochard in winter, whilst White-fronted Goose, Barnacle Goose, Wigeon, Pintail and Goldeneye have also occurred on occasion, generally during cold weather, though the lake is prone to freezing over during prolonged frosts. Snipe can sometimes be found in the ditches by the lake and Reed Buntings breed in the surrounding vegetation, whilst Marsh Harrier and Merlin have been noted overhead. The parkland area around Westenhanger Castle used to hold Spotted Flycatchers but this species has since declined considerably. Black Redstart has been recorded singing from the racecourse buildings and may occasionally breed here. The fields in the Hillhurst Farm area may attract Lapwings and occasionally Golden Plover, whilst when left as stubble in the winter of 2013/14 they held a flock of up to 50 Yellowhammers, together with single Jack Snipe and Corn Bunting, and small numbers of Stock Doves, Sky Larks, Meadow Pipits, Linnets and Reed Buntings. Large numbers of Mediterranean Gulls may be attracted, with a peak count of about 100 in November 2013. Kiln Wood has breeding Buzzard and typical woodland species, including Nuthatch, whilst Woodcock, Siskin and sometimes Lesser Redpoll may winter and the small pond in the wood can attract Mandarin. In May 2009 a singing Wood Warbler was present but was presumably just a migrant.