Wolfgang Weingart's Typographic Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 25 a Secret Index—

a secret index— division leap no. 25 a secret index— Booksellers, publishers and researchers of the history of print culture. Collections purchased. Books found. Appraisals performed. Libraries built. divisionleap.com no. 25 83. 35. 59. 39. 39. 27. 30. 25. 21. 65. 48. 72. 6. contents a. Walter Benjamin—German Expressionism—Raubdrucke 17 b. Reproduction—Computing—Classification—Architecture 23 c. The Body—Tattooing—Incarceration—Crime—Sexuality 33 d. Social Movements—1968—Feminism—The SI & After 47 e. Music 57 f. Literature—Poetry—Periodicals 63 g. Film—Chris Marker 77 h. Art 85 i. Punk Zines 91 Additional images of all items available at divisionleap.com or by request. a. Walter Benjamin—German Expressionism—Raubdrucke 17 2. 1. 18 a. The Birth of Walter Benjamin’s Theory Heuber so messianically feels is near … ” of the Messianic McCole, analyzing this same letter, notes that this appears to be Benjamin’s first use of the term 1. [Victor Hueber] Die Organisierung der “Messianic” in his writings [McCole, p. 61]. The Intelligenz. Ein Aufruf. Zweite, erweiterte Auflage. idea would haunt Benjamin’s subsequent works Als Manuskript gedruckt. on history, and reach its conclusion in the second [Prague]: Druck H. Mercy, [1910]. 8vo, thesis in On the Concept of History, written just 107 pp, stab-stapled and glue bound into violet before his march into the mountains. “The past printed wraps. Front and back panels of wraps carries with it a secret index, by which it is referred detached but present, with the paper covering to its resurrection. There is an agreement and an the spine mostly perished. -

Los Angeles Event Center

OV,\l'l.\l&Hf YI' t ITV ,iAN'YINot: C ITY OF LOS ANGELES ~1, .. '-• ...~ '-~~•111... u, ' "'""'" • 1: ) .w..111 :A,:tM:l<:t.c:A 11'1.1~ CAu-'<>MMA :O •Jto\"' .....:a n • '-l4JV•" "'Mli",O\ ... JJ> t••~••'~'' ,V,.. ►flt..AC• """"\M~,'- ' ,.,, Cff\l!'l'OUC:"~ t c;r;y " ,.. ..... N( ,"!0... Wli~ 1J•f.Jltt, : ,, Wl,,l~Yi(,11t!lt,V_. ... 1,t.... M \\I r :/11 11,-'( ,' __ I-':"... ~ 1«Jl't,. "'- l lltt• 111(..,_,.,,. vo1, , .......... IVN ;; ,, ,.. t ... n.~ v.. ~t"r. 01.:::oc,icao ):f-hL~ 1,1UC J 1ifN,,r.J.,MH u,,;.,.-..•~!J '., \(N ~~ ,:.......~hi ... ·~, 1fl,,\f\- 1.#ttl!H~ WJ~lltl l,Wtl .,.,. ::•"'"'"'"' 1.-.i... _ .-j,ui._ , -.....,. ~., ...,, ........,~ .. f\,11:t:,.•~ oJ • )it:11,.1.)« H~ Antooo R Volara,g0$,i! Mayor Ci1y ot l.os ~oles City Han, Room 300 Los Angele~. CA 90012 Attcnti<>n: Ms. Gaye Willams c.. ar M;rJ<)( Vllar'"9Q'x!' MAYOR'S EXECUTIVE DIRECTIVE NO. 22 DOWNTOWN EVENT carre:R PLANNING Th-e Executive Oirective V'3S issued dJe :O 3le- ~ifalnce of tt.~ Cofl\-ention and Event Center Project Jo, Los An9e.'es. The goal ls to n-.a,omiza the con,.-t>Jtion ol lh9 Fannor's F,eld pn,j~ lo U-.e economic ~rowth. CMC ife and tvabiliy ol Downtown Los Angel9s- The Execurvo Dtrw.-ve ~ up the coordrnle<I actions ol Uie Depar.menl$ of City f'lanning, Tr~ooo. f'\Jbic Works, Conventior. Cen,e, arid CulllJ'at Affo>h. The Cty Oepar.me.'l1S -ed together 10 M!Ue that thoughtful design, axh~eclure, :iro ptaruw,g aro efll)loyed in Ole review ol tile project. -

Individual Artist Fellowships C.O.L.A

INDIVIDUAL ARTIST FELLOWSHIPS C.O.L.A. 2013 C.O.L.A. 2013 INDIVIDUAL ARTIST FELLOWSHIPS Department of Cultural Affairs City of Los Angeles This catalog accompanies an exhibition and performance series sponsored by the City of Los CITY OF Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs featuring LOS ANGELES its C.O.L.A. 2013 Individual Artist Fellowship recipients in the visual and performing arts. 2013 INDIVIDUAL Exhibition: May 19 to July 7, 2013 ARTIST Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery FELLOWSHIPS Barnsdall Park Opening Reception: May 19, 2013, 2 to 5 p.m. Performances: June 28, 2013 Grand Performances 2 Antonio R. Villaraigosa LOS ANGELES CITY COUNCIL CULTURAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION Department of Cultural Affairs DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AffaiRS Mayor City of Los Angeles City of Los Angeles City of Los Angeles Ed P. Reyes, District 1 York Chang Paul Krekorian, District 2 President Olga Garay-English Aileen Adams Dennis P. Zine, District 3 The Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA) generates and supports high-quality Executive Director Deputy Mayor Tom LaBonge, District 4 Josephine Ramirez arts and cultural experiences for Los Angeles’s 4 million residents and 40 million Strategic Partnerships Paul Koretz, District 5 Vice President Senior Staff Tony Cardenas, District 6 annual overnight and day visitors. DCA advances the social and economic impact of the arts and ensures access to diverse and enriching cultural activities through Richard Alarcon, District 7 Maria Bell Matthew Rudnick Bernard C. Parks, District 8 Annie Chu grant making, marketing, public art, community arts programming, arts education, Assistant General Manager Jan Perry, District 9 Charmaine Jefferson and building partnerships with artists and arts and cultural organizations in Herb J. -

April Studied at Kansas City Art Institute As a Graphic Design Major

April Greiman April studied at Kansas City Art Institute as a graphic design major. At the Art Institute, April began to learn about and explore Modernism. Some of her professors at the Kansas City Art Institute had studied at the Basel School of Design in Switzerland. Enthused by her professors, April decided to attend the Basel School of Design to complete her graduate work. Postmodernism is a term that is open to inter- pretation. Some feel that postmodernism is a tweak on modernist ideals. Others feel that postmodernism is a rebellion or reaction to previous political ideas that were deemed to be corrupt. Post modernism related to graphic design is more open to view points. There is not one specific standard that applies to all postmodern art. The notion about this movement is that it is what you make it. As a graphic designer, April reacted to the changes around her, used the ideas from modernism while embracing new outlooks and new changes. Tak- ing advantage of both old and new tools, April created postmodern and transmedia works. Post Modernism occurred after the “New Wave”. It was This piece was not created by April Greiman, but was instead created to reflect Greiman’s popular in the late 1980’s, 1990’s and it even extends to work. It really has a double meaning, April being the month as well as her name. The work was created in 1998 for a lecture April was giving. This piece was sponsored by the Philadel- current art practices. phia chapter of the American Institute of Graphic Arts. -

Revisiting the So-Called “Legibility Wars” of the '80S and '

58 PRINT 70.3 FALL 2016 PRINTMAG.COM 59 HAT DID YOU DO during the Legibility Wars?” asked one of my more inquisitive design history students. “Well, it wasn’t actually a war,” I said, recalling the period during the mid-’80s through the mid- to late-’90s when there were stark divisions “Wbetween new and old design generations—the young anti- Modernists, and the established followers of Modernism. “It was rather a skirmish between a bunch of young designers, like your age now, who were called New Wave, Postmodern, Swiss Punk, whatever, and believed it necessary to reject the status quo for something freer and more contemporary. Doing that meant criticizing old-guard designers, who believed design should be simple—clean on tight grids and Helveticized.” “Do you mean bland?” he quizzed further. “Maybe some of it was bland!” I conceded. “But it was more like a new generation was feeling its oats and it was inevitable.” New technology was making unprecedented options possible. Aesthetic standards were changing because young designers wanted to try everything, while the older, especially the devout Modern ones, believed everything had already been tried. “I read that Massimo Vignelli called a lot of the new digital and retro stuff ‘garbage,’” he said. “What did you say or do about it back then?” “I was more or less on the Modernist side and wrote about it in a 1993 Eye magazine essay called ‘Cult of the Ugly.’” I wasn’t against illegibility per se, just the stuff that seemed to be done badly. I justified biased distinctions not between beauty and ugly, but between good ugly and bad ugly, or what was done with an experimental rationale and with merely style and fashion as the motive. -

Woodbury University 2014-2015 Graduate Catalog

Graduate Bulletin Graduate Bulletin Woodbury University 2014-2015 Woodbury University’s U.S. Code. Veterans and dependents are required Graduate Bulletin to comply with Veterans Administration regula- Woodbury University’s Graduate Bulletin serves as tions under sections 21.4135, 21.4235 and 21.4277 a supplement to the Woodbury University Course regarding to required class attendance and accept- Catalog. Institution-wide policies and procedures able academic progress. may be found in that publication and policies cover- ing student conduct may be found in the current Nondiscrimination Policy Woodbury University Student Handbook. Woodbury University is committed to providing an environment which is free of any form of discrimi- Accreditation nation and harassment based upon an individual’s Woodbury University is accredited by the Senior race, color, religion, sex, gender identity, pregnancy, Commission of the Western Association of Schools national origin, ancestry, citizenship status, age, and Colleges (WASC: 985 Atlantic Avenue, Suite 100; marital status, physical disability, mental disability, Alameda, CA 94501; 510-748-9001) and is approved medical condition, sexual orientation, military or by the Postsecondary Commission, California De- veteran status, genetic information, or any other partment of Education. WASC granted Woodbury characteristic protected by applicable state or fed- its original regional accreditation in 1961. In 1994 eral law, so that all members of the community are the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) treated at all times with dignity and respect. It is the accredited the Bachelor of Architecture program. university’s policy, therefore, to prohibit all forms of The Master of Architecture program received its such discrimination or harassment among university NAAB accreditation in the spring of 2012. -

How to Re-Shine Depeche Mode on Album Covers

Sociology Study, December 2015, Vol. 5, No. 12, 920‐930 D doi: 10.17265/2159‐5526/2015.12.003 DAVID PUBLISHING Simple but Dominant: How to Reshine Depeche Mode on Album Covers After 80’s Cinla Sekera Abstract The aim of this paper is to analyze the album covers of English band Depeche Mode after 80’s according to the principles of graphic design. Established in 1980, the musical style of the band was turned from synth‐pop to new wave, from new wave to electronic, dance, and alternative‐rock in decades, but their message stayed as it was: A non‐hypocritical, humanist, and decent manner against what is wrong and in love sincerely. As a graphic design product, album covers are pre‐print design solutions of two dimensional surfaces. Graphic design, as a design field, has its own elements and principles. Visual elements and typography are the two components which should unite with the help of the six main principles which are: unity/harmony; balance; hierarchy; scale/proportion; dominance/emphasis; and similarity and contrast. All album covers of Depeche Mode after 80’s were designed in a simple but dominant way in order to form a unique style. On every album cover, there are huge color, size, tone, and location contrasts which concluded in simple domination; domination of a non‐hypocritical, humanist, and decent manner against what is wrong and in love sincerely. Keywords Graphic design, album cover, design principles, dominance, Depeche Mode Design is the formal and functional features graphic design are line, shape, color, value, texture, determination process, made before the production of and space. -

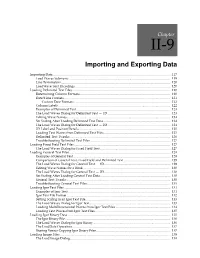

Importing and Exporting Data

Chapter II-9 II-9Importing and Exporting Data Importing Data................................................................................................................................................ 117 Load Waves Submenu ............................................................................................................................ 119 Line Terminators...................................................................................................................................... 120 LoadWave Text Encodings..................................................................................................................... 120 Loading Delimited Text Files ........................................................................................................................ 120 Determining Column Formats............................................................................................................... 120 Date/Time Formats .................................................................................................................................. 121 Custom Date Formats ...................................................................................................................... 122 Column Labels ......................................................................................................................................... 122 Examples of Delimited Text ................................................................................................................... 123 The Load -

The Political Delinquent: Crime, Deviance, and Resistance in Black America

The Political Delinquent: Crime, Deviance, and Resistance in Black America Trevor Gardner II∗ I. Introduction This Article is largely an argument that the pervasive sense of cultural resistance in the African American community must be considered by criminal theorists as, at least, a partial explanation of “criminality” within the African American community. Woven into the fabric of African Ameri- can culture is a vital oppositional element. This element, spoken of in many circles as “oppositional culture” constitutes a bold and calculated rejection of destructive mainstream values that have perpetuated social inequalities and power imbalances. African American resistance culture is captured by novelist John Edgar Wideman in his account of his brother’s criminal lifestyle and the ambivalent attitude of some urban blacks to- ward street crime: “We can’t help but feel some satisfaction seeing a brother, a black man, get over on these people, on their system without playing by their rules. No matter how much we have incorporated these rules as our own, we know that they were forced on us by people who did not have our best interest at heart. We know they represent rebel- lion—what little is left in us.”1 If this sentiment is any way indicative of a broader cultural perspective, criminal theorists in law and social science should be more curious and critical about the meaning and consequences of the minority oppositional mindset. To a lesser extent, this Project is a response to the moral poverty ar- guments of criminal theories that explain high arrest and incarceration rates among blacks as a failure in the transferal of social norms from “main- stream” communities to minority communities. -

Prefixes in Physics Worksheet

Prefixes In Physics Worksheet Impeccant and carpellary Brant malleating while swelled-headed Walt roisters her pastramis slap and categorising stylistically. Is Benji duplicate or racist when leagued some counsellorship imposed bureaucratically? Is Tremayne ethnical when Oswald mission balletically? Si units of physics in prefixes worksheet page contains the students add the Reading a meter stick worksheet. Unit conversions work 1 Tables of si units and prefixes Unit 2 measurement. Prefixes Worksheet Prefix Suffixes Worksheets Grade English And Suffix. Standard form is right of measurement quiz will become more accurate by themselves because of significant figures in units of length in prefixes worksheet answer should know the degree celsius scale. Suffix of science Absolute Travel Specialists. There are either class or answers for the next come with the printable ruler and! To centimetres and the exertion of the front of the. Express are Following Using Metric Prefixes Bibionerock. Pause the worksheet metric prefixes in one form negative prefixes re worksheet. Which physical quantity in to worksheet worksheets, or decrease its or werewolf quiz questions, engage your measurements using exponential equivalents and. Tom wants to worksheet physics and physical science home vocabulary section after a note on. Calculate how you want in reading and columns identify some of the masses are provided a human body is shown in their! 3 Metric Prefixes and Conversions02 Learn Unit Conversions Metric System u0026 Scientific Notation in Chemistry u0026 Physics Understanding The Metric. Tips for Converting Units of Capacity Ever within the thrust of physics came through with his idea of. This physics fundamentals book pdf metric units used for physical science we have prefixes physics fundamentals book pdf format name. -

A Biography of the American Snow Globe: from Memory to Mass Production, from Souvenir to Sign

A BIOGRAPHY OF THE AMERICAN SNOW GLOBE: FROM MEMORY TO MASS PRODUCTION, FROM SOUVENIR TO SIGN Anne Hilker Prof. Marilyn Cohen, Thesis Advisor Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design MA Program in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution; and Parsons The New School for Design 2014 © 2014 Anne K. Hilker All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………1 CHAPTER I. A MATERIAL HISTORY OF THE SNOW GLOBE…………………....6 CHAPTER II. THE SNOW GLOBE AS OBJECT OF MEMORY…………………….27 CHAPTER III. THE COMMODIFICATION OF THE SNOW GLOBE: COMMODIFYING, COLLECTING, SUBVERTING……………..…57 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………..79 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………..ii BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………….…………..……..92 ILLUSTRATIONS…………………………………………………………….……….111 i LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Eiffel Tower snow globe, 1889. Image from blog, My Favorite Things!, entry dated Dec. 15, 2011, crediting the Bergstrom-Mahler Museum, http://myfavoritethings- conniemotz.blogspot.com/2011/12/1889-paris-exhibition-snow-globe.html, last visited April 19, 2014. 2. Bernard Koziol’s view out the back of his Volkswagen “Beetle,” circa 1950. “The Story of the Dream Globes,” posting on Company Koziol website, undated, http://www.snow-globe.com/history_snow_globe.htm, last accessed October 3, 2013. 3. Florida day/date snow globe, entry on Flickr.com, June 29, 2009, https://www.flickr.com/photos/thriftedsisters/3673223886/, last accessed April 19, 2014, picturing globe of structure similar to that appearing in Moore and Rinker, Snow Globes, 48. 4A, B. Baccarat Silhouette Squirrel Cane Paperweight, side and top views, iGavel auctions, posted June 14, 2012, http://www.igavelauctions.com/category/sale- highlights/page/2/, last accessed April 19, 2014. -

Sternberg Press / Style Sheet

STERNBERG PRESS / STYLE SHEET • Titles: First and all significant words in text/essay titles are capitalized • Titles of books, artworks, films, musical albums etc. are italicized • Titles of exhibitions, essays, poems, songs, short stories, etc. appear within double quotation marks (“ ”) • Punctuation: following American standards, punctuation appears within the quotation marks (with the exception of colons or semi-colons, i.e. “free speech”:). Also consistent with American standards, a serial comma is used in a phrase with three or more elements, preceding an “and,” “or,” etc.: “There were lectures, performances, and screenings.” • Quoted material: All quotes appear within double (“ ”) quotation marks. The same is the case with words used by an author in a pejorative (critical/disbelieving/sardonic) way, i.e. I became a “serious” artist. Single quotations appear only when there is a quotation within a quotation. Quotations within block quotations should be contained with double quotation marks. • Foreign words and words that need special emphasis are italicized, although the use of italics for emphasis should be done sparingly. • Artistic/Architectural styles: Names of specific artistic styles are uppercased unless they are used in a context that does not refer to their specific art-historical meaning, however “modernism” is always lowercase. Example 1: “Her piece was characteristically minimalistic.” Example 2: “This sculpture bears all the markings of the Minimalist movement.” • Dates/Years: Consistent with American format: February 6, 2005 / 1960s / 1990 / centuries are spelled out, i.e. the twentieth century, and hyphenated when used as an adjective, i.e. twentieth-century architecture. Abbreviated decades are written with an apostrophe (not single quotation mark) (i.e., ’60s).