The Ice Age in North Hertfordshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Huronian Glaciation

Brasier, A.T., Martin, A.P., Melezhik, V.A., Prave, A.R., Condon, D.J., and Fallick, A.E. (2013) Earth's earliest global glaciation? Carbonate geochemistry and geochronology of the Polisarka Sedimentary Formation, Kola Peninsula, Russia. Precambrian Research, 235 . pp. 278-294. ISSN 0301-9268 Copyright © 2013 Elsevier B.V. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/84700 Deposited on: 29 August 2013 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Earth’s earliest global glaciation? Carbonate geochemistry and geochronology of the 2 Polisarka Sedimentary Formation, Kola Peninsula, Russia 3 4 A.T. Brasier1,6*, A.P. Martin2+, V.A. Melezhik3,4, A.R. Prave5, D.J. Condon2, A.E. Fallick6 and 5 FAR-DEEP Scientists 6 7 1 Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1085, 1081HV 8 Amsterdam 9 2 NERC Isotope Geosciences Laboratory, British Geological Survey, Environmental Science 10 Centre, Keyworth, UK. NG12 5GG 11 3 Geological Survey of Norway, Postboks 6315 Slupen, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway 12 4 Centre for Geobiology, University of Bergen, Postboks 7803, NO-5020 Bergen, Norway 13 5 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of St Andrews, St Andrews KY16 14 9AL, Scotland, UK 15 6 Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre, Rankine Avenue, East Kilbride, Scotland. -

Timeline of Natural History

Timeline of natural history This timeline of natural history summarizes significant geological and Life timeline Ice Ages biological events from the formation of the 0 — Primates Quater nary Flowers ←Earliest apes Earth to the arrival of modern humans. P Birds h Mammals – Plants Dinosaurs Times are listed in millions of years, or Karo o a n ← Andean Tetrapoda megaanni (Ma). -50 0 — e Arthropods Molluscs r ←Cambrian explosion o ← Cryoge nian Ediacara biota – z ←Earliest animals o ←Earliest plants i Multicellular -1000 — c Contents life ←Sexual reproduction Dating of the Geologic record – P r The earliest Solar System -1500 — o t Precambrian Supereon – e r Eukaryotes Hadean Eon o -2000 — z o Archean Eon i Huron ian – c Eoarchean Era ←Oxygen crisis Paleoarchean Era -2500 — ←Atmospheric oxygen Mesoarchean Era – Photosynthesis Neoarchean Era Pong ola Proterozoic Eon -3000 — A r Paleoproterozoic Era c – h Siderian Period e a Rhyacian Period -3500 — n ←Earliest oxygen Orosirian Period Single-celled – life Statherian Period -4000 — ←Earliest life Mesoproterozoic Era H Calymmian Period a water – d e Ectasian Period a ←Earliest water Stenian Period -4500 — n ←Earth (−4540) (million years ago) Clickable Neoproterozoic Era ( Tonian Period Cryogenian Period Ediacaran Period Phanerozoic Eon Paleozoic Era Cambrian Period Ordovician Period Silurian Period Devonian Period Carboniferous Period Permian Period Mesozoic Era Triassic Period Jurassic Period Cretaceous Period Cenozoic Era Paleogene Period Neogene Period Quaternary Period Etymology of period names References See also External links Dating of the Geologic record The Geologic record is the strata (layers) of rock in the planet's crust and the science of geology is much concerned with the age and origin of all rocks to determine the history and formation of Earth and to understand the forces that have acted upon it. -

North Hertfordshire District Council Climate Change Strategy Completed Actions 2020

North Hertfordshire District Council Climate Change Strategy Completed Actions 2020 REDUCING OUR CARBON FOOTPRINT ● We have engaged a consultant to help identify the Council’s current carbon footprint. ◦ We have received a report detailing the carbon emissions from our main sites and buildings, as well as energy efficiency measures and possibilities for investment in renewable energy which could help the Council reduce its carbon footprint. ◦ We have created an action tracker based on the energy efficiency measures recommended in the report. ◦ We are also having the emissions related to the Council’s vehicle fleet, grey fleet, commuting, water, and waste assessed, and expect to receive similar reports for these elements which lay out the opportunities for carbon reduction. ● The Council has made the switch to renewable electricity and green gas to power and heat our buildings. ● The Council has worked with Stevenage Leisure Limited (SLL) to eliminate single use plastics from Leisure Centres and Swimming Pools. ◦ Blue plastic overshoes were removed from Royston Leisure Centre and Hitchin Swim Centre on 13/12/2019 and 24/02/2020 respectively. REDUCING OUR CARBON FOOTPRINT ● Changes to the Taxi and Private Hire Licensing Policy were approved to limit emissions. These changes included: ◦ No idling points system introduced to enforce against drivers who do not comply. ◦ Restricted use taxi ranks - when the infrastructure is in ` place, it is intended to restrict use of prime location taxi ranks to environmentally friendly vehicles. This serves both as an incentive for licence holders to purchase environmentally friendly vehicles and addresses the issue of vehicle emissions in residential areas such as town centres. -

Rpt Global Changes Report to Draft 3

Changes Report - lists projects whose statuses have changed during the entire process Broxbourne ┌ count of other Divisions for project 2017-2018 County Council Division Drafts / Sub Area / Town Project Name IWP Number 2 3 Current Reason for change 01 Cheshunt Central Cheshunt 1 Crossbrook Street Major Patching CWY161104 C C Deferred from 16/17 to 17/18 to avoid other works Cheshunt 1 Great Cambridge Road Major Patching ARP15247 C Deferred from 16/17 to 17/18 due to constructability issues Cheshunt Landmead Footway Reconstruction MEM17061 M M Added due to 17/18 Member HLB funding Cheshunt Roundmoor Drive Footway Reconstruction MEM17062 M M Added due to 17/18 Member HLB funding Turnford 1 Benedictine Gate Thin Surfacing MEM17047 M M Added due to 17/18 Member HLB funding Turnford 1 Willowdene Thin Surfacing MEM17048 M M Added due to 17/18 Member HLB funding Waltham Cross 1 High Street Resurfacing MEM17042 M M Added due to 17/18 Member HLB funding 02 Flamstead End And Turnford Cheshunt Appleby Street Surface Dressing CWY15300 W W Deferred from 16/17 to 17/18 due to works in progress Cheshunt Beaumont Road Surface Dressing CWY151808 W W Deferred from 16/17 to 17/18 due to works in progress Cheshunt Southview Close Thin Surfacing CWY17941 S X Removed 17/18 as duplicate with scheme CWY17977 Cheshunt 1 Whitefields Footway Reconstruction MEM17051 M M Added due to 17/18 Member HLB funding Hammond Street, Cheshunt 1 Hammond Street Road Drainage DRN13034 W Deferred from 12/13 to 17/18 due to works in Investigation progress Rosedale, Cheshunt Lavender -

The History of Ice on Earth by Michael Marshall

The history of ice on Earth By Michael Marshall Primitive humans, clad in animal skins, trekking across vast expanses of ice in a desperate search to find food. That’s the image that comes to mind when most of us think about an ice age. But in fact there have been many ice ages, most of them long before humans made their first appearance. And the familiar picture of an ice age is of a comparatively mild one: others were so severe that the entire Earth froze over, for tens or even hundreds of millions of years. In fact, the planet seems to have three main settings: “greenhouse”, when tropical temperatures extend to the polesand there are no ice sheets at all; “icehouse”, when there is some permanent ice, although its extent varies greatly; and “snowball”, in which the planet’s entire surface is frozen over. Why the ice periodically advances – and why it retreats again – is a mystery that glaciologists have only just started to unravel. Here’s our recap of all the back and forth they’re trying to explain. Snowball Earth 2.4 to 2.1 billion years ago The Huronian glaciation is the oldest ice age we know about. The Earth was just over 2 billion years old, and home only to unicellular life-forms. The early stages of the Huronian, from 2.4 to 2.3 billion years ago, seem to have been particularly severe, with the entire planet frozen over in the first “snowball Earth”. This may have been triggered by a 250-million-year lull in volcanic activity, which would have meant less carbon dioxide being pumped into the atmosphere, and a reduced greenhouse effect. -

23 July 2021

NORTH HERTFORDSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL WEEK ENDING 23 JULY 2021 MEMBERS’ INFORMATION Topic Page News and information 1-4 CCTV Reports - Pre-Agenda, Agenda and Decision sheets 5-16 Planning consultations - Planning applications received & decisions 17-33 Press releases 34-35 Produced by the Communications Team. Any comments, suggestions or contributions should be sent to the Communications Team at [email protected] Page 1 of 35 NEWS AND INFORMATION AGENDA & REPORTS PUBLISHED WEEK COMMENCING 19 JULY 2021 None FORTHCOMING MEETINGS WEEK COMMENCING 26 JULY 2021 None CHAIR’S ENGAGEMENTS WEEK COMMENCING 24 JULY 2021 Date Event Location None VICE-CHAIR’S ENGAGEMENTS WEEK COMMENCING 24 JULY 2021 Date Event Location None OTHER EVENTS WEEK COMMENCING 24 JULY 2021 Date Event Location None Page 2 of 35 REGULATORY SERVICES MEMBERS INFORMATION NOTE North Hertfordshire Local Plan Examination Update The latest consultation on the new Local Plan for the District closed in June 2021. Members of the public and other interested parties were invited to comment upon the latest proposed changes to the Plan and a number of supporting documents. The consultation followed the further hearing public sessions held by the Inspector between November 2020 and February 2021. The Council received approximately 670 responses to the consultation. These contained approximately 1,500 distinct representations on the documents and detailed proposed changes that were consulted upon. The Inspector has now given the go-ahead for the responses to be made public. The independent Programme Officer, who helps administer the Examination, has asked for the website to be updated so that people know that the representations are available to view and to add the following text: The Inspector will be reading and considering all the representations that have been submitted. -

Timing and Tempo of the Great Oxidation Event

Timing and tempo of the Great Oxidation Event Ashley P. Gumsleya,1, Kevin R. Chamberlainb,c, Wouter Bleekerd, Ulf Söderlunda,e, Michiel O. de Kockf, Emilie R. Larssona, and Andrey Bekkerg,f aDepartment of Geology, Lund University, Lund 223 62, Sweden; bDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071; cFaculty of Geology and Geography, Tomsk State University, Tomsk 634050, Russia; dGeological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, ON K1A 0E8, Canada; eDepartment of Geosciences, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm 104 05, Sweden; fDepartment of Geology, University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park 2006, South Africa; and gDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521 Edited by Mark H. Thiemens, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved December 27, 2016 (received for review June 11, 2016) The first significant buildup in atmospheric oxygen, the Great situ secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) on microbaddeleyite Oxidation Event (GOE), began in the early Paleoproterozoic in grains coupled with precise isotope dilution thermal ionization association with global glaciations and continued until the end of mass spectrometry (ID-TIMS) and paleomagnetic studies, we re- the Lomagundi carbon isotope excursion ca. 2,060 Ma. The exact solve these uncertainties by obtaining accurate and precise ages timing of and relationships among these events are debated for the volcanic Ongeluk Formation and related intrusions in because of poor age constraints and contradictory stratigraphic South Africa. These ages lead to a more coherent global per- correlations. Here, we show that the first Paleoproterozoic global spective on the timing and tempo of the GOE and associated glaciation and the onset of the GOE occurred between ca. -

Internal Migration, England and Wales: Year Ending June 2015

Statistical bulletin Internal migration, England and Wales: Year Ending June 2015 Residential moves between local authorities and regions in England and Wales, as well as moves to or from the rest of the UK (Scotland and Northern Ireland). Contact: Release date: Next release: Nicola J White 23 June 2016 June 2017 [email protected] +44 (0)1329 444647 Notice 22 June 2017 From mid-2016 Population Estimates and Internal Migration were combined in one Statistical Bulletin. Page 1 of 16 Table of contents 1. Main points 2. Things you need to know 3. Tell us what you think 4. Moves between local authorities in England and Wales 5. Cross-border moves 6. Characteristics of movers 7. Area 8. International comparisons 9. Where can I find more information? 10. References 11. Background notes Page 2 of 16 1 . Main points There were an estimated 2.85 million residents moving between local authorities in England and Wales between July 2014 and June 2015. This is the same level shown in the previous 12-month period. There were 53,200 moves from England and Wales to Northern Ireland and Scotland, compared with 45,600 from Northern Ireland and Scotland to England and Wales. This means there was a net internal migration loss for England and Wales of 7,600 people. For the total number of internal migration moves the sex ratio is fairly neutral; in the year to June 2015, 1.4 million (48%) of moves were males and 1.5 million (52%) were females. Young adults were most likely to move, with the biggest single peak (those aged 19) reflecting moves to start higher education. -

Treasure Houses of Southern England

TREASURE HOUSES OF SOUTHERN ENGLAND BEHIND THE SCENES OF THE STATELY HOMES OF ENGLAND MAY 6TH - 15TH 2018 We are pleased to present the fi rst in a two-part series that delves into the tales and traditions of the English aristocracy in the 20th century. The English class system really exists nowhere else in the world, mainly because England has never had the kind of violent social revolution that has taken away the ownership of the land from the families that have ruled it since medieval times. Vast areas of the country are still owned by families that can trace their heritage back to the Norman knights who accompanied William the Conqueror. Here is our invitation to discover how this system has come about and to experience the fabulous legacy that it has BLENHEIM PALACE bequeathed to the nation. We have included a fascinating array of visits, to houses both great and small, private and public, spanning the centuries from the Norman invasion to the Victorian era. This spring, join Discover Europe, and like-minded friends, for a look behind the scenes of TREASURE HOUSES OF SOUTHERN ENGLAND. (Note: Part II, The Treasure Houses of Northern England is scheduled to run in September.) THE COST OF THIS ITINERARY, PER PERSON, DOUBLE OCCUPANCY IS: LAND ONLY (NO AIRFARE INCLUDED): $4580 SINGLE SUPPLEMENT: $ 960 Airfares are available from many U.S. cities. Please call for details. THE FOLLOWING SERVICES ARE INCLUDED: HOTELS: 8 nights’ accommodation in fi rst-class hotels All hotel taxes and service charges included COACHING: All ground transportation as detailed in the itinerary MEALS: Full breakfast daily, 4 dinners GUIDES: Discover Europe tour guide throughout BAGGAGE: Porterage of one large suitcase per person ENTRANCES: Entrance fees to all sites included in the itinerary, including private tours of Waddesdon Manor, Blenheim Palace and Stonor Park (all subject to fi nal availability) Please note that travel insurance is not included on this tour. -

Martin G Hoffman ASHWELL Mark Noble Westbrook

ABCDEFGHIJ Any employment, office, Any payment or A description of any Any land in the Council’s Any land in the Council’s Any tenancy where to The name of any person Any other types of interest (other 1 Councillor Parish trade, profession or provision of any other contract for goods, area in which you have area for which you or the your knowledge the or body in which you than Disclosable Pecuniary Spire Furlong 3 Newnham Way Trustee - Ashwell Village Hall Ashwell Trustee - Ashwell Village Museum 2 Martin G Hoffman ASHWELL Retired NONE NONE Herts NONE NONE NONE Vide President - Ashwell Show 33 West End Mark Noble Ashwell 3 Westbrook - White ASHWELL Ambit Projects Limited NONE NONE Herts SG7 5PM NONE NONE NONE 41 Club 3 Orchard View Sunnymead 4 Bridget Macey ASHWELL NONE NONE NONE Ashwell NONE NONE NONE NONE 92 Station Road Ashwell 5 David R Sims ASHWELL NONE NONE NONE Herts SG7 5LT NONE NONE NONE NONE British Association of Counselling & Psychotherapy Foundation for Psychotherapy & Counselling British Psychoanalytical Council Rare Breeds Survival Hebridean Sheep Society Ashwell Housing Association National Sheep Association Guild of Weavers, Spinners and Dyers Member of Green Party Husband: British Association for Local History Hertfordshire Association for Local 59 High Street, Ashwell History (Home) Hertfordshire Record Scoiety Farm fields at: Westbury, Farm fields at: Westbury, Rare Breeds Survival Trust Self-employed Shepherd, Hunts Close, Townsend, Hunts Close, Townsend, Hebridean Sheep Society teacher, landlord Baldwins Corner, -

Hertfordshire County Council

Index of Sites in Stevenage Borough Map Number Site Inset Map 033 ELAS037 Gunnelswood Road Employment Area Inset Map 034 ELAS211 Pin Green Employment Area -90- 522000 522500 523000 523500 524000 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 5 2 2 2 °N 2 0 0 0 0 5 5 4 ELAS037 4 2 2 2 Gunnelswood Road 2 Employment Area (3/4/5) 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 4 2 2 2 2 Stevenage District (B) Size Access Groundwater 0 0 0 0 5 5 3 3 2 2 2 2 0 ELAS037 0 0 0 0 Gunnelswood Road 0 3 3 2 Employment Area (3/5) 2 2 2 0 North Hertfordshire District 0 0 0 5 5 2 2 2 2 2 2 © Crown copyright and database rights 2014 Ordnance Survey 100019606. You are not permitted to copy, sub-licence, distribute or sell any of this data to third parties in any form. 522000 522500 523000 523500 524000 Inset Map 033 Key Allocated Site Existing Safeguarded Strategic Site ELAS 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 Scale 1:12,500 Meters Waste Site Allocations Adopted July 2014 - Stevenage District 525500 526000 526500 North Hertfordshire District °N 0 0 0 0 5 5 7 7 2 2 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 7 2 2 2 2 Size ELAS211 Access Pin Green Employment Area Groundwater 0 0 0 0 5 5 6 6 2 2 2 Stevenage District (B) 2 East Herts District 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 6 2 2 2 2 © Crown copyright and database rights 2014 Ordnance Survey 100019606. -

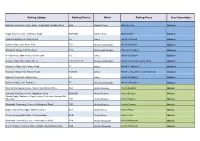

Polling Station List

Polling Station Polling District Ward Polling Place Area Committee Baldock Community Centre, Large / Small Halls, Simpson Drive AAA Baldock Town Baldock Town Baldock Tapps Garden Centre, Wallington Road ABA,ABB Baldock East Baldock East Baldock Ashwell Parish Room, Swan Street FA Arbury Parish of Ashwell Baldock Sandon Village Hall, Payne End FAA Weston and Sandon Parish of Sandon Baldock Wallington Village Hall, The Street FCC Weston and Sandon Paish of Wallington Baldock The Old Forge, Manor Farm, Church Lane FD Arbury Parish of Bygrave Baldock Weston Village Hall, Maiden Street FDD, FDD1, FE Weston and Sandon Parishes of Weston and Clothall Baldock Hinxworth Village Hall, Francis Road FI Arbury Parish of Hinxworth Baldock Newnham Village Hall, Ashwell Road FS1,FS2 Arbury Parishes of Caldecote and Newnham Baldock Radwell Village Hall, Radwell Lane FX Arbury Parish of Radwell Baldock Rushden Village Hall, Rushden FZ Weston and Sandon Parish of Rushden Baldock Westmill Community Centre, Rear of John Barker Place BAA Hitchin Oughton Hitchin Oughton Hitchin Catholic Parish Church Hall, Nightingale Road BBA,BBD Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Hitchin Rugby Clubhouse, King Georges Recreation Ground, Old Hale Way BBB Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Walsworth Community Centre, 88 Woolgrove Road BBC Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Bearton Hitchin Baptist Church Hall, Upper Tilehouse Street BCA Hitchin Priory Hitchin Priory Hitchin St Johns Community Centre, St Johns Road BCB Hitchin Priory Hitchin Priory Hitchin Walsworth Community Centre, 88 Woolgrove Road BDA Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin New Testament Church of God, Hampden Road/Willian Road BDB Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Polling Station Polling District Ward Polling Place Area Committee St Michaels Community Centre, St Michaels Road BDC,BDD Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Walsworth Hitchin Benslow Music Trust- Fieldfares, Benslow Lane BEA Hitchin Highbury Hitchin Highbury Hitchin Whitehill J.M.