SOAG Bulletin 65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Pages Farm House Oxfordshire Pages Farm House Oxfordshire

PAGES FARM HOUSE OXFORDSHIRE PAGES FARM HOUSE OXFORDSHIRE A charming secluded Oxfordshire farmhouse set within a cobbled courtyard in an idyllic and private valley with no through traffic and within 1.5 miles of livery yard. Reception hall • Drawing room • Sitting room • Family room • Dining room Kitchen (with Aga)/breakfast room • Walk-in larder • Utility room • Cellar Ground floor guest bedroom and shower room • Wooden and tiled floors. Master bedroom with en suite bathroom • 1 Bedroom with dressing room and bathroom 3 Further bedrooms with family bathroom Staff/guest flat with: Living room • Kitchen • 2 Bedrooms both with en-suite bathrooms Separate studio Barn Guest cottage/Home office with: Large reception room • Shower room • 2 Attic rooms Gardens and grounds with fine views from the southfacing terrace over adjoining farmland • Vegetable garden • Duck pond orchard In all about 1.1 acres (with room for tennis court and swimming pool) Knight Frank LLP Knight Frank LLP 20 Thameside 55 Baker Street Henley-on-Thames London Oxfordshire RG9 2LJ W1U 8AN +44 1491 844 900 +44 20 7629 8171 [email protected] [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation (All distances and times are approximate) • Henley-on-Thames – 5 miles • Oxford – 24 miles • Central London – 40 miles • Heathrow – 30 miles • M40 (J5) – 11 miles • M4 (J8/9) – 14 miles • Henley-on-Thames Station – 5 miles (London Paddington from 45 mins) • High Wycombe Station – 18 miles (London Marylebone 30 mins) • Rupert House School – Henley • Shiplake College • Queen Anne’s – Caversham • The Dragon School • Radley College • Wycombe Abbey • The Royal Grammar School – High Wycombe • Sir William Borlaise School – Marlow • Henley Golf Club • Badgemore Park • Huntercombe Golf Club Cellar Barn Ground Floor Barn First Floor First Floor Approximate Gross Internal Floor Area House - 591.9 sq.mts. -

The Perils of Periodization: Roman Ceramics in Britain After 400 CE KEITH J

The Perils of Periodization: Roman Ceramics in Britain after 400 CE KEITH J. FITZPATRICK-MATTHEWS North Hertfordshire Museum [email protected] ROBIN FLEMING Boston College [email protected] Abstract: The post-Roman Britons of the fifth century are a good example of people invisible to archaeologists and historians, who have not recognized a distinctive material culture for them. We propose that this material does indeed exist, but has been wrongly characterized as ‘Late Roman’ or, worse, “Anglo-Saxon.” This pottery copied late-Roman forms, often poorly or in miniature, and these pots became increasingly odd over time; local production took over, often by poorly trained potters. Occasionally, potters made pots of “Anglo-Saxon” form using techniques inherited from Romano-British traditions. It is the effect of labeling the material “Anglo-Saxon” that has rendered it, its makers, and its users invisible. Key words: pottery, Romano-British, early medieval, fifth-century, sub-Roman Archaeologists rely on the well-dated, durable material culture of past populations to “see” them. When a society exists without such a mate- rial culture or when no artifacts are dateable to a period, its population effectively vanishes. This is what happens to the indigenous people of fifth-century, lowland Britain.1 Previously detectable through their build- ings, metalwork, coinage, and especially their ceramics, these people disappear from the archaeological record c. 400 CE. Historians, for their part, depend on texts to see people in the past. Unfortunately, the texts describing Britain in the fifth-century were largely written two, three, or even four hundred years after the fact. -

826 INDEX 1066 Country Walk 195 AA La Ronde

© Lonely Planet Publications 826 Index 1066 Country Walk 195 animals 85-7, see also birds, individual Cecil Higgins Art Gallery 266 ABBREVIATIONS animals Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum A ACT Australian Capital books 86 256 A La RondeTerritory 378 internet resources 85 City Museum & Art Gallery 332 abbeys,NSW see New churches South & cathedrals Wales aquariums Dali Universe 127 Abbotsbury,NT Northern 311 Territory Aquarium of the Lakes 709 FACT 680 accommodationQld Queensland 787-90, 791, see Blue Planet Aquarium 674 Ferens Art Gallery 616 alsoSA individualSouth locations Australia Blue Reef Aquarium (Newquay) Graves Gallery 590 activitiesTas 790-2,Tasmania see also individual 401 Guildhall Art Gallery 123 activitiesVic Victoria Blue Reef Aquarium (Portsmouth) Hayward Gallery 127 AintreeWA FestivalWestern 683 Australia INDEX 286 Hereford Museum & Art Gallery 563 air travel Brighton Sea Life Centre 207 Hove Museum & Art Gallery 207 airlines 804 Deep, The 615 Ikon Gallery 534 airports 803-4 London Aquarium 127 Institute of Contemporary Art 118 tickets 804 National Marine Aquarium 384 Keswick Museum & Art Gallery 726 to/from England 803-5 National Sea Life Centre 534 Kettle’s Yard 433 within England 806 Oceanarium 299 Lady Lever Art Gallery 689 Albert Dock 680-1 Sea Life Centre & Marine Laing Art Gallery 749 Aldeburgh 453-5 Sanctuary 638 Leeds Art Gallery 594-5 Alfred the Great 37 archaeological sites, see also Roman Lowry 660 statues 239, 279 sites Manchester Art Gallery 658 All Souls College 228-9 Avebury 326-9, 327, 9 Mercer Art Gallery -

Download Map (PDF)

How to get there Driving: Postcode is RG8 0JS and a car park for customers. Nearest station: Goring & Streatley station is 2.1 miles away. Local bus services: Go Ride route 134 stops just outside the pub. We’re delighted to present three circular walks all starting and ending at the Perch & Pike. The Brakspear Pub Trails are a series of circular walks. Brakspear would like to thank the Trust for We thought the idea of a variety of circular country walks Oxfordshire’s Environment all starting and ending at our pubs was a guaranteed and the volunteers who winner. We have fantastic pubs nestled in the countryside, helped make these walks possible. As a result of these and we hope our maps are a great way for you to get walks, Brakspear has invested in TOE2 to help maintain out and enjoy some fresh air and a gentle walk, with a and improve Oxfordshire’s footpaths. guaranteed drink at the end – perfect! Reg. charity no. 1140563 Our pubs have always welcomed walkers (and almost all of them welcome dogs too), so we’re making it even easier with plenty of free maps. You can pick up copies in the pubs taking part or go to brakspearaletrails.co.uk Respect - Protect - Enjoy to download them. We’re planning to add new pubs onto Respect other people: them, so the best place to check for the latest maps • Consider the local community and other people available is always our website. enjoying the outdoors We absolutely recommend you book a table so that when • Leave gates and property as you find them and follow paths unless wider access is available you finish your walk you can enjoy a much needed bite to eat too. -

Time for a New Approach

Henley & Wallingford Artist Trail 19-27 May 2012 Time for a new approach. We believe that it’s through taking time to understand each individual, their likes and dislikes and their life stories, we can provide personal care with a real difference. Acacia Lodge Care Home, in Henley-on-Thames is a purpose built home offering exceptional nursing, residential and dementia care in beautiful and comfortable surroundings. Beyond the 55 spacious en-suite rooms are a host of social facilities, including a bar, library, hair salon, and treatment room. For further information please call 01491 430 093 Acacia Lodge Nursing, Residential & Dementia Care or email [email protected] Care Home Quebec Road, Henley-on-Thames Oxfordshire, RG9 1EY www.acacialodgecarehome.co.uk Acacia Lodge_Oxfordshire_Artworks_Guide_210x148.indd 1 29/02/2012 09:36 Each venue is open on the highlighted dates between 19th - 27th May. Most open 12-6pm. Refer to the Artweeks Festival Guide or www.artweeks.org for further details. 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 Grant Waters OAS Ken Messer, Anna Dillon OAS, Jenny Fay, Jacqueline Fitzjohn Janet Callender Alan Wilson Painting Susanna Brunskill Melita Kyle Roberta Tetzner Painting Painting, Sculpture Unit 8, Hall Farm, Painting JewelleryMixed Media, Painting Mixed Media, Painting CeramicsPottery Gardener’s Cottage, Greys Court Farm, South Moreton Twitten, Aston Street, Heathersage, Free Church Hall, Gor- Charity Farm Barns, Shepherd’s Green, Rotherfield Greys, OX11 9FD Aston Tirrold, Aston Street, ing Free Church, High Goring Heath RG8 7RR Henley-on-Thames Henley-on-Thames nr Didcot OX11 9DQ Aston Tirrold OX11 9DJ Street, RG8 9AT RG9 4QL RG9 4PG 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 Hamptons Artways Art Club Acacia Lodge Artspace Anne Arlidge OCG Jane White Braziers Park International Various Drawing, Painting Glass Ceramics presents.. -

Team Profile for the Appointment of a House for Duty Team Vicar to Serve the Villages of Ipsden and North Stoke Within the Langtree Team Ministry

TEAM PROFILE FOR THE APPOINTMENT OF A HOUSE FOR DUTY TEAM VICAR TO SERVE THE VILLAGES OF IPSDEN AND NORTH STOKE WITHIN THE LANGTREE TEAM MINISTRY The Appointment The Bishop of Dorchester and the Team Rector are seeking to appoint a Team Vicar to serve two of the rural parishes which make up the Langtree Team Ministry. The Langtree Team is in a large area of outstanding natural beauty and lies at the southern end of the Chilterns. It is in the Henley Deanery and the Dorchester Archdeaconry of the Diocese of Oxford. The villages lie in an ancient woodland area once known as Langtree, with Reading to the south (about 12 miles), Henley-on-Thames to the east (about 10 miles) and Wallingford to the northwest (about 3 miles). The Team was formed in 1981 with Checkendon, Stoke Row and Woodcote. In 1993 it was enlarged to include the parishes of Ipsden and North Stoke with Mongewell. The Team was further enlarged in 2003 to include the parish of Whitchurch and Whitchurch Hill. The combined electoral roll (2019) for our parishes was 308. The Team’s complete ministerial staff has the Team Rector serving Checkendon and Stoke Row, a stipendiary Team Vicar at Woodcote and non-stipendiary Team Vicars on a house- for-duty basis serving (a) Ipsden and North Stoke and (b) Whitchurch and Whitchurch Hill. There is a licensed Reader, a non-stipendiary Team Pastor and a part time Administrator. The Langtree Team staff provide support for the parishes in developing their response to local ministry needs. -

Castle Studies Group Bibliography No. 23 2010 CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 23 (2010)

Castle Studies Group Bibliography No. 23 2010 CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 23 (2010) By John R. Kenyon Introduction This is advance notice that I plan to take the recent publications compilation to a quarter century and then call it a day, as I mentioned at the AGM in Taunton last April. So, two more issues after this one! After that, it may be that I will pass on details of major books and articles for a mention in the Journal or Bulletin, but I think that twenty-five issues is a good milestone to reach, and to draw this service to members to a close, or possibly hand on the reins, if there is anyone out there! No sooner had I sent the corrected proof of last year’s Bibliography to Peter Burton when a number of Irish items appeared in print. These included material in Archaeology Ireland, the visitors’ guide to castles in that country, and then the book on Dublin from Four Court Press, a collection of essays in honour of Howard Clarke, which includes an essay on Dublin Castle. At the same time, I noted that a book on medieval travel had a paper by David Kennett on Caister Castle and the transport of brick, and this in turn led me to a paper, published in 2005, that has gone into Part B, Alasdair Hawkyard’s important piece on Caister. Wayne Cocroft of English Heritage contacted me in July 2009, and I quote: - “I have just received the latest CSG Bibliography, which has prompted me to draw the EH internal report series to your attention. -

Excavations at Dover 1945-1947 Threipland

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society EXCAVATIONS AT DOVER, 1945-1947 By LESLIE MURRAY TBREEPLAND , B.A., F.S.A., and K. A. STEER, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. DURING the 1939-45 war, the town of Dover, lying between the chalk downs at the mouth of the River Dour, twenty miles from the French coast, suffered severely from bombing and cross-Channel shelling. Towards the end of the war a Committee was formed under the Presidency of the Lord Bishop of Dover, with the object of examining some of the razed sites (Fig. 1) before they were rebuilt, to find out more of the history of the town in the Roman period. DOVER . PLAN SHEW1NG WAR DAMAGED AREAS IN THE CENTRE OF TOWN AND EXCAVATIONS 19451 7 pit 7 Fie. 1 130 DOVER, SHOWING ROMAN SITES, APPROXIMATE EXTENT OP ROMAN FOR TRE.5.5(snADED)AN -0 PROBABLE LINE Or ME D1AEVAL TOWN WALLS. fOuNORTIONI FOUNO I int Match t,..11e4 EXCAVATIONS AT DOVER, 1945-7 Dover is mentioned by the Notitia Dignitatum as the site of a Saxon shore fort,' but was probably one of the ports of the Classis Britannica at a much earlier date. Professor R. E. M. Wheeler, writing in 1929,2 gave an account of the Roman remains found there by chance discoveries and observation of building operations. He suggested, tentatively, on the available evidence, a position for the Roman fort on the west side of the Dour and in the north-west corner of the medieval fortifications (Fig. -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

Where to See Red Kites in the Chilterns AREA of OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY

For further information on the 8 best locations 1 RED l Watlington Hill (Oxfordshire) KITES The Red Kite - Tel: 01494 528 051 (National Trust) i Web: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/regions/thameschilterns in the l2 Cowleaze Wood (Oxfordshire) Where to Chilterns i Tel: 01296 625 825 (Forest Enterprise) Red kites are magnificent birds of prey with a distinctive l3 Stokenchurch (Buckinghamshire) forked tail, russet plumage and a five to six foot wing span. i Tel: 01494 485 129 (Parish Council Office limited hours) see Red Kites l4 Aston Rowant National Nature Reserve (Oxfordshire) i Tel: 01844 351 833 (English Nature Reserve Office) in the Chilterns l5 Chinnor (Oxfordshire) 60 - 65cm Russet body, grey / white head, red wings i Tel: 01844 351 443 (Mike Turton Chinnor Hill Nature Reserve) with white patches on underside, tail Tel: 01844 353 267 (Parish Council Clerk mornings only) reddish above and grey / white below, 6 West Wycombe Hill (Buckinghamshire) tipped with black and deeply forked. l i Tel: 01494 528 051 (National Trust) Seen flying over open country, above Web: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/regions/thameschilterns woods and over towns and villages. 7 The Bradenham Estate (Buckinghamshire) m l c Tel: 01494 528 051 (National Trust) 5 9 Nests in tall trees within woods, i 1 Web: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/regions/thameschilterns - sometimes on top of squirrel’s dreys or 5 8 The Warburg Reserve (Oxfordshire) 7 using old crow's nests. l 1 i Tel: 01491 642001 (BBOWT Reserve Office) Scavenges mainly on dead animals Email:[email protected] (carrion), but also takes insects, Web: www.wildlifetrust.org.uk/berksbucksoxon earthworms, young birds, such as crows, weight 0.7 - 1 kg and small mammals. -

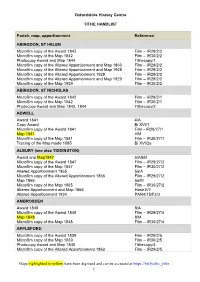

Oxfordshire Tithe Map Handlist

Oxfordshire History Centre TITHE HANDLIST Parish, map, apportionment Reference ABINGDON, ST HELEN Microfilm copy of the Award 1842 Film – IR29/2/2 Microfilm copy of the Map 1842 Film – IR30/2/2 Photocopy Award and Map 1844 Tithecopy/1 Microfilm copy of the Altered Apportionment and Map 1860 Film – IR29/2/2 Microfilm copy of the Altered Apportionment and Map 1928 Film – IR29/2/2 Microfilm copy of the Altered Apportionment 1929 Film – IR29/2/2 Microfilm copy of the Altered Apportionment and Map 1929 Film – IR29/2/2 Microfilm copy of the Map 1929 Film – IR30/2/2 ABINGDON, ST NICHOLAS Microfilm copy of the Award 1842 Film – IR29/2/1 Microfilm copy of the Map 1842 Film – IR30/2/1 Photocopy Award and Map 1842, 1844 Tithecopy/2 ADWELL Award 1841 4/A Copy Award Bi XVI/1 Microfilm copy of the Award 1841 Film - IR29/27/1 Map 1841 4/M Microfilm copy of the Map 1841 Film – IR30/27/1 Tracing of the Map made 1885 Bi XVI/2a ALBURY (see also TIDDINGTON) Award and Map1847 5/A&M Microfilm copy of the Award 1847 Film – IR29/27/2 Microfilm copy of the Map 1847 Film – IR30/27/2 Altered Apportionment 1865 5a/A Microfilm copy of the Altered Apportionment 1865 Film – IR29/27/2 Map 1865 5a/M Microfilm copy of the Map 1865 Film – IR30/27/2 Altered Apportionment and Map 1865 Hase II/2 Altered Apportionment 1934 PAR4/15/F3/3 AMBROSDEN Award 1848 8/A Microfilm copy of the Award 1848 Film – IR29/27/4 Map 1848 8/M Microfilm copy of the Map 1848 Film – IR30/27/4 APPLEFORD Microfilm copy of the Award 1839 Film – IR29/2/5 Microfilm copy of the Map 1839 Film – IR30/2/5