Place Meanings in the Broughton Archipelago By: Matthew Bowes Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Master I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Community Plan Bylaw 15-2011

PLAN THE ADVENTURE AHEAD THE DISTRICT OF PORT HARDY OFFICIAL COMMUNITY PLAN BYLAW No. 15-2011 AS AMENDED Consolidation: May 27, 2014 CONSOLIDATED COPY FOR CONVENIENCE ONLY Amending Bylaws: Bylaw 1025-2014 · Text Amendment: Sec 7.10.3 Development Permit Exemptions · Map 1 Land Use: Changing the land use designation of a portion of the property which is legally described as Northwest ¼ of Section 25, Township 9, Rupert District, Except Part in Plan 49088, from Rural Resource to Industrial and Comprehensive Development A BYLAW TO ADOPT THE DISTRICT OF PORT HARDY OFFICIAL COMMUNITY PLAN DISTRICT OF PORT HARDY BYLAW No. 15-2011 GIVEN THAT the District of Port Hardy wishes to adopt an Official Community Plan; The Council of the District of Port Hardy in open meeting assembled ENACTS as follows: 1. This bylaw may be cited as the "Official Community Plan Bylaw No. 15-2011". 2. The plan titled District of Port Hardy Official Community Plan set out in Schedule A to this bylaw is adopted and designated as the Official Community Plan for the District of Port Hardy. 3. Bylaw No. 18-99, 1999, Official Community Plan for the District of Port Hardy, as amended is repealed. Read a first time the 13th day of September, 2011. Read a second time the 13th day of September, 2011. Read a third time the 11th day of October, 2011. Adopted the 11th day of October, 2011. ORIGINAL SIGNED BY: ______________________________ ______________________________ Director of Corporate Services Mayor Certified to be a true copy of District of Port Hardy Official Community Plan Bylaw No. -

Pre-Hospital Triage and Transport Guidelines for Adult and Pediatric Major Trauma in British Columbia

2019 PROVINCIAL GUIDELINE Pre-hospital Triage and Transport Guidelines for Adult and Pediatric Major Trauma in British Columbia Trauma Services BC A service of the Provincial Health Services Authority Contents Foreword ..........................................................................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................................4 Adult and Pediatric Pre-hospital Trauma Triage Guidelines – Principles .........................................................................5 Step One – Physiological ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Step Two – Anatomical ........................................................................................................................................................7 Step Three – Mechanism ................................................................................................................................................... 8 Step Four – Special Considerations .................................................................................................................................. 8 Pre-hospital Trauma Triage Standard – British Columbia .....................................................................................................9 -

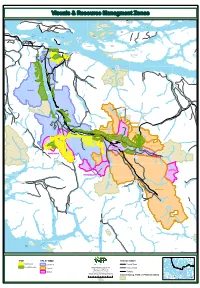

Visuals & Resource Managment Zones

Visuals & Resource Managment Zones Port Elizabeth Trinity G I L F O R D I S L A N D Bay BROUGHTON ARCHIPELAGO Single Tree CONSERVANCY Pt. SUQUASH Lady Islands BROUGHTON ARCHIPELAGO Knight Inlet Sointula MARINE " PARK Mitchell Village Bay Island BROUGHTON Swanson CORMORANT CHANNEL Island Ledge Pt. CORMORANT Cluxewe STRAIT CHANNEL Port McNeill Harbour MARINE Turnour Island PARK Port McNeill Alert Bay " " Clio Channel Harbledown Island Flagstaff Is. Hanson Island WHITE DUCK LAKE Telegraph Cove " LOWER NIMPKISH Beaver Cove QWIQUALLAAQ/BOAT West Cracroft Island PARK BAY CONSERVANCY Cub Lake J O H N S T O N E ROBSON BIGHT (MICHAEL Robson BIGG) ECOLOGICAL Bight RESERVE LOWER TSITIKA RIVER PARK TSITIKA MOUNT MOUNTAIN DERBY ECOLOGICAL ECOLOGICAL RESERVE RESERVE Nimpkish Nimpkish Lake Bonanza Lake Tsitika NIMPKISH Nimpkish LAKE " PARK CLAUDE ELLIOTT ECOLOGICAL RESERVE TSITIKA RIVER ECOLOGICAL MOUNT RESERVE ELLIOTT ECOLOGICAL RESERVE CROSS LAKE Woss-Vernon Highway 19 Woss-Vernon Tsitika Atluck Lake Woss " TAHSISH Woss-Vernon KWOIS PARK TSITIKA-WOSS SCHOEN LAKE PINDER-ATLUCK PARK Woss-Vernon Lower Schoen Klaklakama Lake TAHSISH Lake RIVER ECOLOGICAL RESERVE ARTLISH CAVES PARK Woss Lake SCHOEN- STRATHCONA Tahsish Inlet WOSS-ZEBELLOS . Moketas Island WOSS LAKE PARK NIMPKISH RIVER ECOLOGICAL Fair Harbour RESERVE " DIXIE COVE MARINE PARK Woss-Vernon Vernon Lake Zeballos " Zeballos Inlet Espinosa Inlet Tahsis " Port Eliza WEYMER CREEK PARK TAHSIS INLET Muchalat Lake GOLD MUCHALAT PARK CATALA ISLAND MARINE PARK Catala ESPERANZA INLET Island NUCHATLITZ PARK "" VQO TFL37 RMZ Transportation Sayward " Modification Enhanced Paved Road Partial Retention Tree Farm Licence 37 General Gravel Road " Management Plan 10 Woss Special Overview Map - Jan. -

Copyrighted Material

CONTENTS LIST OF MAPS vii 1 THE BEST OF BRITISH COLUMBIA & THE CANADIAN ROCKIES 1 1 The Best Travel Experiences . .1 8 The Most Dramatic Drives. .8 2 The Best Active Vacations . .2 9 The Best Walks & Rambles. .8 3 The Best Nature- & 10 The Best Luxury Hotels & Resorts. .9 Wildlife-Viewing . .3 11 The Best B&Bs & Country Inns . .10 4 The Best Family-Vacation 12 The Best Rustic Accommodations: Experiences. .4 Lodges, Wilderness Retreats & 5 Native Canadian Culture & Log-Cabin Resorts . .11 History. .5 13 The Best Northwest Regional 6 The Best Museums & Cuisine . .12 Historic Sites . .6 14 The Best Festivals & Special 7 The Most Scenic Views . .7 Events . .14 2 BRITISH COLUMBIA & THE CANADIAN ROCKIES IN DEPTH 15 1 British Columbia & the Canadian 4 Books, Film & Music: British Rockies Today. .15 Columbia & the Canadian 2 Looking Back at British Columbia Rockies in Popular Culture . .23 & the Canadian Rockies . .16 5 A Taste of British Columbia & 3 The Lay of the Land . .21 the Canadian Rockies . .26 3 PLANNINGCOPYRIGHTED YOUR TRIP TO BRITISH MATERIAL COLUMBIA & THE CANADIAN ROCKIES 29 1 When to Go. .29 3 Getting There & Getting Around. .36 Calendar of Events . .33 4 Money & Costs. .39 2 Entry Requirements . .34 5 Health . .40 Bringing Children into Canada . .35 6 Safety . .41 002_591536-ftoc.indd2_591536-ftoc.indd iiiiii 44/28/10/28/10 110:510:51 AAMM iv 7 Specialized Travel Resources . .41 10 Escorted General-Interest Tours . .45 8 Sustainable Tourism. .43 11 Staying Connected. .46 9 Active Vacation Planner . .43 4 SUGGESTED ITINERARIES IN BRITISH COLUMBIA & THE CANADIAN ROCKIES 48 1 The Canadian Rockies in 1 3 The Wild & the Sophisticated on Week. -

Telegraph Cove & Zeballos Cruise

Telegraph Cove Whale watching TELEGRAPH COVE & Activity Level: 2 ZEBALLOS CRUISE September 18, 2021 – 4 Days All Meals Included (10): 3 breakfasts, 4 lunches, 3 dinners Whale watching at Telegraph Cove & Fares per person: private charter cruise on MV Uchuck $1,490 double/twin; $1,825 single; $1,420 triple Please add 5% GST. Vancouver Island is the 11th largest island in Early Bookers: $80 discount on first 12 seats; $40 on next 8 Canada, stretching 460 km from the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Queen Charlotte Experience Points: Sound. Named for Captain George Earn 34 points on this tour. Vancouver who explored B.C.’s coast in Redeem 34 points if you book by July 29, 2021. 1792, the island has great diversity ranging from the capital city of Victoria to remote mountain peaks in Strathcona Park, and from narrow fjords that slice into the west coast to secluded harbours like Telegraph Cove. To explore northern Vancouver Island properly, you have to get out of your car (or coach) and head out on the water. You could add another photo here This tour features a whale-watching excursion at Telegraph Cove and a private Whale Centre cruise on the MV Uchuck III from Zeballos to Gold River through several scenic waterways. ITINERARY Day 1: Saturday, September 18 Day 3: Monday, September 20 After pickups around Greater Victoria, we drive This morning, we drive to Zeballos, a tiny com- north on the Island Highway with a stop for lunch munity at the end of a fjord on the west coast of in Parksville. -

Partnerschulen in Kanada British Columbia – Vancouver Island

PARTNERSCHULEN IN KANADA BRITISH COLUMBIA – VANCOUVER ISLAND Türkenstraße 104 80799 München Telefon 089 / 35 73 79 77 [email protected] www.map-highschoolyear.com MAP MUNICH ACADEMIC PROGRAM GMBH [email protected] HIGH SCHOOLS IN KANADA (BRITISH COLUMBIA – VANCOUVER ISLAND) Schuldistrikt Schule Ort Seite Campbell River Carihi Secondary School Campbell River 1 Timberline Secondary School Campbell River 1 Comox Valley G.P. Vanier Secondary School Courtenay 3 Highland Secondary School Comox 4 Mark Isfeld Secondary School Courtenay 4 Cowichan Valley Chemainus Secondary Chemainus 5 Cowichan Secondary Duncan 5 Frances Kelsey Secondary Mill Bay 6 Lake Cowichan Secondary Lake Cowichan 6 Gulf Islands Gulf Islands Secondary School Ganges, Saltspring Island 7 Nanaimo Ladysmith Dover Bay Secondary School Nanaimo 8 John Barsby Secondary School Nanaimo 8 Ladysmith Secondary School Ladysmith 9 Nanaimo District Secondary School Nanaimo 9 Wellington Secondary School Nanaimo 10 Pacific Rim Alberni District Secondary School Port Alberni 11 Ucluelet Secondary School Ucluelet 11 Qualicum Ballenas Secondary School Parksville 13 Kwalikum Secondary School Qualicum Beach 13 Saanich Claremont Secondary School Cordova Bay (Victoria) 14 Parkland Secondary School Sidney 14 Stelly's Secondary School Saanichton 15 Sooke Belmont Secondary School Langford 16 Edward Milne Community School Sooke 17 Royal Bay Secondary School Sooke 17 Victoria Esquimalt High School Victoria 18 Lambrick Park Secondary School Victoria 18 Mount Douglas Secondary School Victoria 19 Oak Bay High School Victoria 19 Reynolds Secondary School Victoria 20 Spectrum Community School Victoria 20 Victoria High School Victoria 21 Privatschule Glenlyon Norfolk School (GNS) Victoria 22 Shawnigan Lake School (Internat) Shawnigan Lake 23 MAP MUNICH ACADEMIC PROGRAM GMBH [email protected] HIGH SCHOOLS IN KANADA (BRITISH COLUMBIA – VANCOUVER ISLAND) BRITISH COLUMBIA / VANCOUVER ISLAND Die Provinz British Columbia liegt im Westen Kanadas an der Küste des Pazifischen Ozeans. -

P a C I F I C R E G I

PACIFIC REGION INTEGRATED FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PLAN SALMON SOUTHERN B.C. JUNE 1, 2005 - MAY 31, 2006 Oncorhynchus spp This Integrated Fisheries Management Plan is intended for general purposes only. Where there is a discrepancy between the Plan and the Fisheries Act and Regulations, the Act and Regulations are the final authority. A description of Areas and Subareas referenced in this Plan can be found in the Pacific Fishery Management Area Regulations. TABLE OF CONTENTS DEPARTMENT CONTACTS INDEX OF INTERNET-BASED INFORMATION GLOSSARY 1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................11 2. GENERAL CONTEXT .............................................................................................................12 2.1. Background.................................................................................................................12 2.2. New Directions ...........................................................................................................12 2.3. Species at Risk Act .....................................................................................................15 2.4. First Nations and Canada’s Fisheries Framework ......................................................16 2.5. Pacific Salmon Treaty.................................................................................................17 2.6. Research......................................................................................................................17 -

“Spring Break” in BC

We take ordinary and m ake it Extraordinary “Spring Break” in BC Orca, Vancouver Island 10 Day Whales, Bears & Vancouver Island BRITISH COLUMBIA SELF DRIVE HOLIDAY 10 days/ 9 nights Victoria to Port Hardy (or in reverse) Port Hardy Telegraph Cove Highlights: Sightseeing on Vancouver Island’s many scenic drives, Whale & Bear watching excursions from Victoria and Tofino staying in comfortable Inns & B&B’s. Campbell River Departs: Daily from April to October Tono Pacic Rim NP Day 1: Victoria Check into your hotel and spend the day Victoria discovering the capital of British Columbia with it’s turn of the century architecture. Day 2: Victoria Grizzly Bear Safaris by boat and visit Knight Enjoy an included 2 hour food/history tour of Inlet and the Great Bear Rainforest. During your Victoria, learn about the history of Chinatown, Olde stay we have included a full day Grizzly Bear Town and the Inner Harbour as you taste your way Exploration which includes lunch. along the route. This afternoon we recommend a Day 8: Telegraph Cove visit to the world famous Butchart Gardens. Black Bear At leisure to Explore the historic village of Telegraph Cove, take a whale watching kayak Day 6: Campbell River to Telegraph Cove tour, go looking for Bears, or spend the day with There is time this morning to discover the islands a First Nations Guide discovering the Kingcome and waterways around Campbell River, try your Valley by jet boat. hand at fishing, enjoy a wildlife viewing cruise, visit Elk Falls Provincial Park where you can view Day 9: Telegraph Cove to Port Hardy salmon spawning, walk along the many forest A short drive brings you to Port Hardy, visit Cape trails. -

Broughton Group

Kayak Destinations Broughton Group Queen Charlotte Strait/Johnstone Strait, BC Paddling Notes West side of Johnstone Strait without crossing to archipelago Water Taxi to Echo Bay and return paddle to Port McNeil or Telegraph Cove Water taxi to Mound Island from Telegraph Cove Trip Options Extensive Day Paddles from Paddler’s Inn, near Echo Bay Guided trips in area, mostly Johnstone Strait and Blakney Passage General Exposed and Sheltered options July and August, are best times, not overly crowded in archipelago Wilderness camping - tend to be for small groups of 3-4 tents Carry at least 4 days of water in archipelago. Reliable water only on Vancouver I. side of Johnstone Strait, such as at Kaikash Creek. Killer whales follow migratory salmon runs in late July, and often are easily viewed - observe proper viewing guidelines. Humpback whales also in area. First Nations sites of interest, especially at Village Island and Alert Bay Good fishing in archipelago Cautions Fog, wind, currents, tides, cruise ships, rip tides. Blakney passage/Johnstone Strait/Cracroft Point area Cold Water in Q. Charlotte Strait - wet/dry suits + dress for warmth Observe current and tide tables, incl. secondary stations Trip Basics No. of Days 3-8 days Paddle Distance 20-50 nm SKGBC Water Class. Map (I-IV) Class II – Among inner island groups Class III - Johnstone Strait and Queen Charlotte Strait Recommended Launch Site: Telegraph Cove - Launch Fee, kayak rentals, parking, camping, restaurants Port McNeil – Water Taxi to Echo Bay area. Getting -

Regional Visitors Map

Regional Visitors Map www.vancouverislandnorth.ca Boomer Jerritt - Sandy beach at San Josef Bay BC Ferries Discovery Coast Port Hardy - Prince RupertBC Ferries Inside Passage Port Hardy - Bella Coola Wakeman Sound www.bcbudget.com Mahpahkum-Ahkwuna Nimmo Bay Kingcome Deserters-Walker Kingcome Inlet 1-888-368-7368 Hope Is. Conservancy Drury Inlet Mackenzie Sound Upper Blundon Sullivan Kakwelken Harbour Bay Lake Cape Sutil Nigei Is. Shuttleworth Shushartie North Kakwelken Bight Bay Goletas Channel Balaclava Is. Broughton Island God’s Pocket River Christensen Pt. Nahwitti River Water Taxi Access (privately operated) Wishart Kwatsi Bay 24 Provincial Park Greenway Sound Peninsula Strandby River Strandby Shushartie Saddle Hurst Is. Bond Sd Nissen 49 Nels Bight Queen Charlotte Strait Lewis Broughton Island Knob Hill Duncan Is. Cove Tribune Channel Mount Cape Scott Bight Doyle Is. Hooper Viner Sound Hansen Duval Is. Lagoon Numas Is. Echo Bay Guise Georgie L. Bay Eden Is. Baker Is. Marine Provincial Thompson Sound Cape Scott Hardy William L. 23 Bay 20 Provincial Park PORT Peel Is. Brink L. HARDY 65 Deer Is. 15 Nahwitti L. Kains L. 22 Beaver Lowrie Bay 46 Harbour 64 Bonwick Is. 59 Broughton Gilford Island Tribune ChannelMount Cape 58 Woodward 53 Archipelago Antony 54 Fort Rupert Health Russell Nahwitti Peak Provincial Park Bay Mountain Trinity Bay 6 8 San Josef Bay Pemberton 12 Midusmmer Is. HOLBERG Hills Knight Inlet Quatse L. Misty Lake Malcolm Is. Cape 19 SOINTULA Lady Is. Ecological 52 Rough Bay 40 Blackfish Sound Palmerston Village Is. 14 COAL Reserve Broughton Strait Mitchell Macjack R. 17 Cormorant Bay Swanson Is. Mount HARBOUR Frances L. -

Connected Coast Communities Prince Rupert North Coast Regional District Regional District of Alberni-Clayoquot

Connected Coast Communities Prince Rupert North Coast Regional District Regional District of Alberni-Clayoquot Dodge Cove Ahousaht Hartley Bay (Gitga'at First Nation) Bamfield Kitkatla (Gitxaala Nation) Hesquiaht O l d M a s s e t Lax Kw'alaams Hesquiat Metlakatla First Nation Huu-ay-aht Old Massett (Old Massett Village Council) Huu-ay-aht First Nations Oona River Marktosis Kitimat-Stikine Regional District Opitsat (Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations) Klemtu (Kitasoo) Tla-o-qui-aht Central Coast Regional District Tofino Bella Bella (Heiltsuk) Toquaht Bella Coola Uchucklesaht Duncanby Landing Ucluelet Martin Valley Capital Regional District Ocean Falls Beecher Bay Oweekeno (Wuikinuxv Nation) Fernwood Denny Island-Shearwater Fulford Harbour Mount Waddington Regional District Ganges Alert Bay Musgrave Landing Bull Harbour (Tlatlasikwala) Pacheedaht First Nation Coal Harbour Port Renfrew Da'naxda'xw First Nation Port Washington Echo Bay River jordan Gwa'Sala-Nakwaxda'xw Saturna Bella Coola Gwawaenuk Tribe Shirley Health Bay (Kwikwasut'inuxw Haxwa'mis) Sidney Holberg T'Sou-ke Hyde Creek Victoria Kingcome (Dzawada'enuxw First Nation) Cowichan Valley Regional District Kwakiutl Chemainus (Stz'uminus First Nation) Mahatta River Ditidaht Mamalilikulla-Qwe'Qwa'Sot'Em (First Nation) Lyackson Mitchell Bay Penelakut (Penelakut Tribe) Namgis First Nation Regional District of Nanaimo Port Hardy Bowser Port McNeill Nanaimo Quatsino Nanoose First Nation Quatsino First Nation Qualicum Beach Rumble Beach Comox Valley Regional District Shawl Bay Comox Sointula Williams -

Regional Report on the Status of Pacific Salmon

The status of Pacific salmon in the Broughton Archipelago, northeast Vancouver Island, and mainland inlets A report from © Salmon Coast Field Station 2020 Salmon Coast Field Station is a charitable society and remote hub for coastal research. Established in 2001, the Station supports innovative research, public education, community outreach, and ecosystem awareness to achieve lasting conservation measures for the lands and waters of the Broughton Archipelago and surrounding areas. General Delivery, Simoom Sound, BC V0P 1S0 Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw territory [email protected] | www.salmoncoast.org Station Coordinators: Amy Kamarainen & Nico Preston Board of Directors: Andrew Bateman, Martin Krkošek, Alexandra Morton, Stephanie Peacock, Scott Rogers Cover photo: Jordan Manley Photos on pages 30, 38: April Bencze Suggested citation: Atkinson, EM, CE Guinchard, AM Kamarainen, SJ Peacock & AW Bateman. 2020. The status of Pacific salmon in the Broughton Archipelago, northeast Vancouver Island, and mainland inlets. A report from Salmon Coast Field Station. Available from www.salmoncoast.org 1 Status of Pacific Salmon in Area 12 | For the salmon How are you, salmon? Few fish, but glimmers of hope Sparse data, blurred lens 2 Status of Pacific Salmon in Area 12 | For the salmon Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................... 4 Motivation & Background ................................................................................................. 5 The