Included in This Second Issue of a 3-Volume Series of Bibliographies with Abstracts Are 115 Items Dealing with Significant Mater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Ethnic Crisis and Newspaper Media Performance in Sri Lanka (Related to Selected Newspaper Media from April of 1983 to September of 1983)

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 1, Ver. 8 (January. 2018) PP 25-33 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org A Study on Ethnic Crisis and Newspaper Media performance in Sri Lanka (Related to selected Newspaper media from April of 1983 to September of 1983) Assistant Lecturer Sarasi Chaya Bandara Department of Political Science University of Kelaniya Kelaniya Corresponding Author: Assistant Lecturer Sarasi Chaya Bandara Abstract: The strong contribution denoted by media, in order to create various psychological printings to contemporary folk consciousness within a chaotic society which is consist of an ethnic conflict is extremely unique. Knowingly or unknowingly media has directly influenced on intensification of ethnic conflict which was the greatest calamity in the country inherited to a more than three decades history. At the end of 1970th decade, the newspaper became as the only media which is more familiar and which can heavily influence on public. The incident that the brutal murder of 13 military officers becoming victims of terrorists on 23rd of 1983 can be identified as a decisive turning point within the ethnic conflict among Sinhalese and Tamils. The local newspaper reporting on this case guided to an ethnical distance among Sinhalese and Tamils. It is expected from this investigation, to identify the newspaper reporting on the case of assassination of 13 military officers on 23rd of July 1983 and to investigate whether that the government and privet newspaper media installations manipulated their own media reporting accordingly to professional ethics and media principles. The data has investigative presented based on primary and secondary data under the case study method related with selected newspapers published on July of 1983, It will be surely proven that journalists did not acted to guide the folk consciousness as to grow ethnical cordiality and mutual trust. -

29 Complaints Against Newspapers

29 complaints against newspapers PCCS, Colombo, 07.06.2007 The Press Complaints Commission of Sri Lanka had received 29 complaints against newspapers during the first quarter of this year of which the commission had dealt with. A statement by the commission on its activities is as follows: The Press Complaints Commission of Sri Lanka (PCCSL) was established three and a half years ago (Oct. 2003) by the media to resolve disputes between the press, and the public speedily and cost-effectively, for both, the press and the public, outside the statutory Press Council and the regular courts system. We hope that the PCCSL has made things easier for editors and journalists to dispose of public complaints on matters published in your newspapers, and at no costs incurred in the retention of lawyers etc. In a bid to have more transparency in the work of the Dispute Resolution Council of the PCCSL, the Commission decided to publish the records of the complaints it has received. Complaints summary from January - April 2007 January PCCSL/001/01/2007: Thinakkural (daily) — File closed. PCCSL/OO2/O1/2007: Lakbima (daily)— Goes for mediation. PCCSL/003 Divaina (daily)- Resolved. PGCSL/004/01 /2007: Mawbima — Resolved. (“Right of reply” sent direct to newspaper by complainant). PCCSL/005/01/2007: Lakbima (Sunday) — Goes for mediation. February PCCSL/OO 1/02/2007: The Island (daily) — File closed. PCCSL/O02/02/2007: Divaina (daily) — File closed. F’CCSL/003/02/2007: Lakbima (daily) File closed. PCCSL/004/02/2007: Divaina (daily)— File closed. PCCSL/005/02/2007: Priya (Tamil weekly) — Not valid. -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

WHO Reports Most Coronavirus Cases in a Day As Cases Near Five Million

‘SUPER CYCLONE' ELECTIONS COMMISSION THE CURIOUS CASE THURSDAY BARRELS TOWARDS TELLS SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH ASIA'S MAY 21, 2020 BANGLADESH, INDIA IT CANNOT HOLD POLLS ‘LOW' CORONAVIRUS VOL: 4 - ISSUE 365 ON JUNE 20 DEATHS PAGE 02 HOT TOPICS GLOCAL PAGE 04 EYE ON ASIA 30. PAGE 03 Registered in the Department of Posts of Sri Lanka under No: QD/146/News/2020 A NASA Earth Observatory image Tropical Cyclone Amphan at 16:15 Universal Time (9:45 p.m. India COVID-19 and Standard Time) on Tuesday (19) as it moved north-northeast over the Bay of Bengal. The image is a curfew in Sri Lanka composite of brightness tempera- ture data acquired by the Moderate • One new case of COVID-19 was confirmed yesterday Resolution Imaging Spectroradi- (20), taking Sri Lanka’s tally of the novel coronavirus in- ometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra fection to 1028. Thirty five cases were confirmed by late satellite, overlaid on Black Marble Tuesday (19) night. Four hundred thirty five individuals night-time satellite imagery. Mil- are receiving treatment, 584 have been deemed complete- lions of people battened down yes- ly recovered and nine have succumbed to the virus. terday (20) as the strongest cyclone • Curfew to continue in the Colombo and Gampaha Dis- in decades slammed into Bangladesh tricts till further notice, but with the resumption of civilian and eastern India, killing at least life and economic activities. three and leaving a trail of devasta- • An 8:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. curfew is in force in all districts tion. -

India Progressive Writers Association; *7:Arxicm

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 124 936 CS 202 742 ccpp-.1a, CsIrlo. Ed. Marxist Influences and South Asaan li-oerazure.South ;:sia Series OcasioLal raper No. 23,Vol. I. Michijar East Lansing. As:,an Studies Center. PUB rAIE -74 NCIE 414. 7ESF ME-$C.8' HC-$11.37 Pius ?cstage. 22SCrIP:0:", *Asian Stud,es; 3engali; *Conference reports; ,,Fiction; Hindi; *Literary Analysis;Literary Genres; = L_tera-y Tnfluences;*Literature; Poetry; Feal,_sm; *Socialism; Urlu All India Progressive Writers Association; *7:arxicm 'ALZT:AL: Ti.'__ locument prasen-ls papers sealing *viithvarious aspects of !',arxi=it 2--= racyinfluence, and more specifically socialisr al sr, ir inlia, Pakistan, "nd Bangladesh.'Included are articles that deal with _Aich subjects a:.the All-India Progressive Associa-lion, creative writers in Urdu,Bengali poets today Inclian poetry iT and socialist realism, socialist real.Lsm anu the Inlion nov-,-1 in English, the novelistMulk raj Anand, the poet Jhaverchan'l Meyhani, aspects of the socialistrealist verse of Sandaram and mash:: }tar Yoshi, *socialistrealism and Hindi novels, socialist realism i: modern pos=y, Mohan Bakesh andsocialist realism, lashpol from tealist to hcmanisc. (72) y..1,**,,A4-1.--*****=*,,,,k**-.4-**--4.*x..******************.=%.****** acg.u.re:1 by 7..-IC include many informalunpublished :Dt ,Ivillable from othr source r.LrIC make::3-4(.--._y effort 'c obtain 1,( ,t c-;;,y ava:lable.fev,?r-rfeless, items of marginal * are oft =.ncolntered and this affects the quality * * -n- a%I rt-irodu::tior:; i:";IC makes availahl 1: not quali-y o: th< original document.reproductiour, ba, made from the original. -

The Day of the African Child 30 Years On, Where Are We Now? Page 2

The Day of the African Child 30 years on, where are we now? Page 2: Adelaide Benneh Prempeh Advancing the Welfare of children in Ghana Page 18: Maria Mbeneka Child Marriage Page 22: Presentation Judge Fatoumata Dembélé Page 23: Diarra – Mali Euridce Baptista – Angola Page 24: CLA Role of the Law in Eliminating Child Marriage 2/10/21 ADVANCING THE WELFARE OF CHILDREN IN GHANA. Presented By: Adelaide Benneh Prempeh Managing Partner B&P ASSOCIATES 1 OVERVIEW u GHANAIAN HISTORICAL CONTEXT & BACKGROUND. u THE CHILD & FAMILY PROTECTION SYSTEM IN GHANA. u LEGAL FRAMEWORK. u LEGISLATIVE REFORM IN GHANA’S ADOPTION LAW. u ADVANCING CHILDREN’S RIGHTS FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT- EDUCATION. 2 1 2/10/21 I. GHANAIAN HISTORICAL CONTEXT & BACKGROUND 3 In the Ghanaian context “Best interests of the Child” will includes cultural perspective and respect for customary structure. Ø Extended family environment. Ø Benefits: Children are allowed to remain in a familiar environment, still connected with their natural family; safety net for children to receive support within family and community. Ø Challenges: Lack of an enforced legal regime to govern this type of “informal family arrangement” for more vulnerable children, as well as the inherent difficulty in monitoring such social arrangements, lends itself to corporal punishment, domestic violence, sexual abuse, sexual violence and exploitation, ritual servitude (Trokosi). 4 2 2/10/21 II. CHILD & FAMILY PROTECTION SYSTEM IN GHANA. 5 2013 International Social Service Report. Ø Weaknesses in the alternative care system/ fosterage. Ø Open adoption of children. Ø Child trafficking. 6 3 2/10/21 Technical Committee Recommendations: Ø Robust child protection framework; Ø Strong regulatory and supervisory institutions; Ø Licensing and accreditation of agencies; Ø Financing of residential facilities; and Ø Comprehensive Child and Family Framework. -

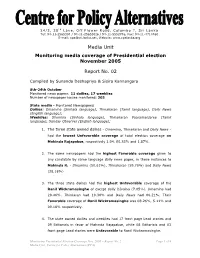

Monitoring Media Coverage of Presidential Election November 2005

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Report No. 02 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara 8th-24th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 205 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); 1. The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.04. 00.33% and 1.87%. 2. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda R. - Dinamina (50.61%), Thinakaran (59.70%) and Daily News (38.18%) 3. The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe of except daily DIvaina (7.05%). Dinamina had 29.46%. Thinkaran had 10.30% and Daily News had 06.21%. Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe was 08.26%, 5.11% and 09.18% respectively. 4. The state owned dailies and weeklies had 17 front page Lead stories and 09 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 08 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. Monitoring Presidential Election Coverage Nov. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

PDF995, Job 7

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara First week from nomination: 8th-15th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 94 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); • The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.14, 00% and 1.82%. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda Rajapakse. - Dinamina (43.56%), Thinakaran (56.21%) and Daily News (29.32%). • The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe, of any daily news paper. Dinamina had 28.82%. Thinkaran had 8.67% and Daily News had 12.64%. • Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe, was 10.75%, 5.10% and 11.13% respectively. • The state owned dailies and weeklies had 04 front page Lead stories and 02 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 02 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. State media coverage of two main candidates (in sq.cm% of total election coverage) Mahinda Rajapakshe Ranil W ickramasinghe Newspaper Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable Dinamina 43.56 1.14 10.75 28.88 Silumina 28.82 10.65 18.41 30.65 Daily news 29.22 1.82 11.13 12.64 Sunday Observer 23.24 00 12.88 00.81 Thinakaran 56.21 00 03.41 00.43 Thi. -

Assassination Attempt

ARMY CONVERTS APPAREL FACTORY MAKING OF A ‘FREE CRIME’ ZONE INTO COVID FACILITY AS SRI LANKA SCRAMBLES FOR BEDS MAY 07 - 09, 2021 UK AND FRANCE SEND NAVAL VOL: 4- ISSUE 246 SHIPS TO CHANNEL ISLAND IN . TENSE FISHING DISPUTE THE PRODUCTIVE PROFLIGATE 30 GLOCAL PAGE 03 EYE ON EUROPE PAGE 05 COMMENTARY PAGE 08 LITERARY LIVES PAGE 11 Registered in the Department of Posts of Sri Lanka under No: QD/130/News/2021 India’s neighbours close borders over virus rampage COLOMBO - Sri Lanka on Thursday (6) became the latest of In- dia's neighbours to seal its borders with the South Asian giant as it battles a record coronavirus surge. Bangladesh and Nepal have also banned flights and sought to close their borders with India, where a huge rise in numbers in the past three weeks has taken deaths past 230,000 and cases over 21 million. All three countries are fighting their own pandemic surg- es, which Red Cross leaders have described as a "human catastro- phe". The Sri Lankan government banned flight passengers from India entering, as the country reported its highest daily toll of 14 deaths and 1,939 infections in 24 hours. Sri Lanka's navy said it had stepped up patrols to keep away Indian trawlers, adding that on Tuesday (4) it stopped 11 such vessels which had crossed the nar- row strip of sea dividing the two neighbours. Bangladesh halted all international flights on April 14 because of its own surge and shut its border with India on April 26. It has reported 11,755 COVID-19 deaths and 767,338 cases, but experts say the real figures are higher in all South Asian countries. -

Freedom of Expression in Sri Lanka: How the Sri Lankan Constitution Fuels Self-Censorship and Hinders Reconciliation

Freedom of Expression in Sri Lanka: How the Sri Lankan Constitution Fuels Self-Censorship and Hinders Reconciliation By Clare Boronow Human Rights Study Project University of Virginia School of Law May 2012 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 II. FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND SELF -CENSORSHIP .................................................................... 3 A. Types of self-censorship................................................................................................... 4 1. Good self-censorship .................................................................................................... 4 2. Bad self-censorship....................................................................................................... 5 B. Self-censorship in Sri Lanka ............................................................................................ 6 III. SRI LANKA ’S CONSTITUTION FACILITATES THE VIOLATION OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, THEREBY PROMOTING SELF -CENSORSHIP ............................................................................ 11 A. Express textual limitations on the freedom of expression.............................................. 11 B. The Constitution handcuffs the judiciary ....................................................................... 17 1. All law predating the 1978 Constitution is automatically valid ................................. 18 2. Parliament may enact unconstitutional -

News Sri Lanka

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY News FROM Sri Lanka May – august 2015 • NuMBER 5 • SRI LaNKa E02 Expands Outreach and Services with JICA Assistance Sri Lanka Streamlines Weather Tracking JICA Volunteer Contributes to Develop Palmyra Products INSIDE E02 Expands Outreach and Services with JICA Assistance Pages–1 & 2 Water for the Needy at Beruwala Page–3 Outer Circular Expressway – Phase II – final touches in progress Replanting Coconut to Regain Rural Livelihoods The Kaduwela to Kadawatha section of capital, an additional interchange Page–4 Colombo Outer Circular Expressway was constructed subsequently in JICA’s Role in the (E02) is the latest transport sector Athurugiriya. Environmental Sector in project financed by JICA towards Sri Lanka The Outer Circular Expressway Pages–5 & 6 enhancing economic development of Sri Lanka Streamlines Sri Lanka. JICA provided financing extends the Southern Expressway Weather Tracking for both the Kottawa-Kaduwela and (E01) northwards from Kottawa Pages–7 & 8 Kaduwela-Kadawatha sections of Interchange. The E02 will also Achievements of Two 20 Year-old JICA Projects the E02 toll expressway. The Road allow vehicle speed up to 100km/h, Page–9 similar to E01, of which 66km Development Authority under the JICA Volunteer Ministry of University Education were financed by JICA. Once the Contributes to Develop 3rd section from Kaduwela to Palmyrah Products and Highways implements the Outer Page–10 Kerawalapitiya is completed, the Circular Expressway project. JICA Issues Landslide Outer Circular Expressway will link Mitigation Project The first section of E02 was opened Southern Expressway and Colombo Review to the public earlier with a major Katunayake Expressway. It will Helping Hands interchange at Kottawa and a then act as a North-South artery for the Disabled in Anuradhapura and temporary interchange at Kaduwela for Colombo bypassing the inner Ratnapura east (Kotalawala), which is now part city area, thereby easing traffic Page–11 of the main Kaduwela interchange.