Inclusion of Woolly Mammoth Mammuthus Primigenius in Appendix II Proponent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 State of Ivory Demand in China

2012–2014 ABOUT WILDAID WildAid’s mission is to end the illegal wildlife trade in our lifetimes by reducing demand through public awareness campaigns and providing comprehensive marine protection. The illegal wildlife trade is estimated to be worth over $10 billion (USD) per year and has drastically reduced many wildlife populations around the world. Just like the drug trade, law and enforcement efforts have not been able to resolve the problem. Every year, hundreds of millions of dollars are spent protecting animals in the wild, yet virtually nothing is spent on stemming the demand for wildlife parts and products. WildAid is the only organization focused on reducing the demand for these products, with the strong and simple message: when the buying stops, the killing can too. Via public service announcements and short form documentary pieces, WildAid partners with Save the Elephants, African Wildlife Foundation, Virgin Unite, and The Yao Ming Foundation to educate consumers and reduce the demand for ivory products worldwide. Through our highly leveraged pro-bono media distribution outlets, our message reaches hundreds of millions of people each year in China alone. www.wildaid.org CONTACT INFORMATION WILDAID 744 Montgomery St #300 San Francisco, CA 94111 Tel: 415.834.3174 Christina Vallianos [email protected] Special thanks to the following supporters & partners PARTNERS who have made this work possible: Beijing Horizonkey Information & Consulting Co., Ltd. Save the Elephants African Wildlife Foundation Virgin Unite Yao Ming Foundation -

Destruction of Confiscated Elephant Ivory in Times Square: Questions and Answers

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Destruction of Confiscated Elephant Ivory in Times Square: Questions and Answers Why is the United States destroying ivory than we needed for these purposes elephant ivory? and decided to destroy that stockpile as We want to send a clear message that a demonstration of our commitment to the United States will not tolerate combating wildlife trafficking. ivory trafficking and is committed to protecting elephants from extinction. The Have other countries destroyed ivory toll these crimes are taking on elephant stockpiles? populations, particularly in Africa, is Yes. The following lists the governments at its worst in decades. The United and the year they destroyed ivory: States believes that it is important Kenya, 1989, 1991, 2011, 2015; Zambia, to destroy ivory seized as a result of 1992; United Arab Emirates, 1992, 2015; law enforcement investigations and at Gabon, 2012; Philippines, 2013; China, international ports of entry. Destroying 2014, 2015; Chad, 2014; France, 2014; this ivory tells criminals who engage in Belgium 2014; Hong Kong 2014; Ethiopia poaching and trafficking that the United 2015; and Congo, 2015. States will take all available measures to disrupt and prosecute those who prey Why doesn’t the Service sell the ivory? on, and profit from, the deaths of these The Service does not sell confiscated magnificent animals. wildlife or products derived from endangered and threatened species. Has the U.S. Government ever done this Illegal ivory trade is driving a dramatic before? increase in African elephant poaching, Yes. On November 14, 2013, at the U.S. Photo: Samples of seized ivory. -

Quarterlyspring 2000 Volume 49 Number 2

AWI QuarterlySpring 2000 Volume 49 Number 2 ABOUT THE COVER For 25 years, the tiger (Panthera tigris) has been on Appendix I of the Conven- tion on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), but an illegal trade in tiger skins and bones (which are used in traditional Chinese medicines) persists. Roughly 5,000 to 7,000 tigers have survived to the new millennium. Without heightened vigilance to stop habitat destruction, poaching and illegal commercialization of tiger parts in consuming countries across the globe, the tiger may be lost forever. Tiger Photos: Robin Hamilton/EIA AWI QuarterlySpring 2000 Volume 49 Number 2 CITES 2000 The Future of Wildlife In a New Millennium The Eleventh Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 11) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) will take place in Nairobi, Kenya from April 10 – 20, 2000. Delegates from 150 nations will convene to decide the fate of myriad species across the globe, from American spotted turtles to Zimbabwean elephants. They will also examine ways in which the Treaty can best prevent overexploitation due to international trade by discussing issues such as the trade in bears, bushmeat, rhinos, seahorses and tigers. Adam M. Roberts and Ben White will represent the Animal Welfare Institute at the meeting and will work on a variety of issues of importance to the Institute and its members. Pages 8–13 of this issue of the AWI Quarterly, written by Adam M. Roberts (unless noted otherwise), outline our perspectives on a few of the vital issues for consideration at the CITES meeting. -

An Illusion of Complicity: Terrorism and the Illegal Ivory Trade in East Africa Occasional Paper

Over 180 years of independent defence and security thinking The Royal United Services Institute is the UK’s leading independent think-tank on international defence and security. Its mission is to be an analytical, research-led global Royal United Services Institute forum for informing, influencing and enhancing public debate on a safer and more stable for Defence and Security Studies world. Since its foundation in 1831, RUSI has relied on its members to support its activities, sustaining its political independence for over 180 years. Occasional Paper London | Brussels | Nairobi | Doha | Tokyo | Washington, DC An Illusion of Complicity Terrorism and the Illegal Ivory Trade in East Africa Tom Maguire and Cathy Haenlein An Illusion of Complicity: Terrorism and the Illegal Ivory Trade in East Africa Occasional Paper Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies Whitehall London SW1A 2ET United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7747 2600 www.rusi.org RUSI is a registered charity (No. 210639) An Illusion of Complicity Terrorism and the Illegal Ivory Trade in East Africa Tom Maguire and Cathy Haenlein Occasional Paper, September 2015 Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies Over 180 years of independent defence and security thinking The Royal United Services Institute is the UK’s leading independent think-tank on international defence and security. Its mission is to be an analytical, research-led global forum for informing, influencing and enhancing public debate on a safer and more stable world. Since its foundation in 1831, RUSI has relied on its members to support its activities, sustaining its political independence for over 180 years. -

The Ivory Trade: the Single Greatest Threat to Wild Elephants

THE IVORY TRADE: THE SINGLE GREATEST THREAT TO WILD ELEPHANTS Elephants have survived in the wild for 15 million years, but today this iconic species is threatened with extinction due to ongoing poaching for ivory. As long as there is demand for ivory, elephants will continue to be killed for their tusks. According to best estimates, as many as 26,000 elephants are killed every year simply to extract their tusks. A Brief History of the Ivory Trade Demand for ivory first skyrocketed in the 1970s and 1980s. The trade in ivory was legal then -- although for the most part it was taken illegally. During those decades, approximately 100,000 elephants per year were being killed. The toll on African elephant populations was shocking: over the course of a single decade, their numbers dropped by half. In October of 1989 the UN Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) voted to move African elephants from Appendix II to Appendix I, affording the now highly endangered animal the maximum level of protection, effectively ending trade in all elephant parts, including ivory. With the new Appendix 1 listing, the poaching of elephants literally stopped overnight. The ban brought massive awareness of the plight of elephants, the bottom dropped out of the market, and prices plummeted. Ivory was practically unsellable. For 10 years, the global ban stood strong and it seemed the crisis had ended. Elephant numbers began to recover. Unfortunately, the resurgence in elephant populations, while nowhere near the numbers prior to the spike in trade, was nevertheless a catalyst for some African countries to consider reopening the trade. -

Doc. 6.21 CONVENTION on INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN

Doc. 6.21 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA Sixth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties Ottawa (Canada), 12 to 24 July 1987 Interpretation and Implementation of the Convention Trade in Ivory from African Elephants SECRETARIAT REPORT ON OPERATION OF THE QUOTA SYSTEM 1. At its fifth meeting (Buenos Aires, 1985), the Conference of the Parties adopted Resolution Conf. 5.12, "Trade in Ivory from African Elephants", establishing new procedures for the control of international trade in ivory from African elephants. These procedures are collectively referred to as the "ivory export quota system", and the key element is the opportunity for establishment of an annual ivory export quota by each state having a population of African elephants and wishing to export raw ivory. 2. Non-Party producer states may also submit an export quota, and any non-Party wishing to import, export or re-export raw ivory must meet all requirements of the Resolution. Unless a non-Party has informed to the contrary, it is assumed to be not conforming with the requirements. 3. The Secretariat was directed to co-ordinate the implementation of the system including maintaining a central database, receiving annual quotas from producer countries and circulating them, preparing a manual of procedures for implementing the system and providing advice on the conservation status of African elephants. An implementation manual, "Ivory Trade Control Procedures", was written by the Secretariat and distributed to all Party and non-Party countries in November 1985. The report, "Establishment of African Ivory Export Quotas and Associated Control Procedures" prepared by Rowan B. -

Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade

Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade Trade Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade The Costs of Crime, Insecurity and Institutional Erosion Katherine Lawson and Alex Vines Katherine Lawson and Alex Vines February 2014 Chatham House, 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0)20 7957 5700 E: [email protected] F: +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration Number: 208223 Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade The Costs of Crime, Insecurity and Institutional Erosion Katherine Lawson and Alex Vines February 2014 © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2014 Chatham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: + 44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978 1 78413 004 6 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Cover image: © US Fish and Wildlife Service. Six tonnes of ivory were crushed by the Obama administration in November 2013. Designed and typeset by Soapbox Communications Limited www.soapbox.co.uk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Latimer Trend and Co Ltd The material selected for the printing of this report is manufactured from 100% genuine de-inked post-consumer waste by an ISO 14001 certified mill and is Process Chlorine Free. -

Ivory Case Study

Ivory Case Study I: Ivory World WISE Seizure Data Analysis of illegal ivory (kg) data was based on seizure records in World WISE from 2005 to 2014. Source of shipment does not necessarily indicate origin of the specimen. Destination of shipment does not necessarily indicate the final destination and could indicate a transit country. Ivory and ivory pieces were used in the analysis and conversions were applied to convert number of items to kg. See table for details on conversions. Figure. Seized Ivory (kg), 2005 to 2014. Conversions applied. Table. Conversions for seized ivory in World WISE, 2005 to 2014. Commodity types Weight Units (no. of items) Comments Includes Ivory pieces and tusks all Final Ivory conversions 124130kg 0 converted to kilograms. A conversion ratio of 1 ivory piece to Ivory Pieces 24920 kg 5640 3.66 kg of ivory was used. A conversion ratio of 1 tusk to 5.45 kg Tusks 99209 kg 9296 of ivory was used. 22 Summary tables for weight of ivory (kg) seized, according to seizure records in World WISE, 2005 to 2014. Conversion applied. Table. Weight of ivory (kg) seized with information on source of shipment or destination of shipment, 2005 to 2014. Conversion applied. Weight of Ivory % of total Weight of Ivory % of total Source of shipment Destination of shipment (kg) seized (kg) seized Source of shipment 103,121 83% Destination of shipment 95,636 77% Unknown source 21,009 17% Unknown destination 28,494 23% Total seized 124,130 100% Total seized 124,130 100% Sources: World WISE Sources: World WISE Table. -

Elephant Ivory Trade-Related Timeline with Relevance to the United States

Elephant Ivory Trade-Related Timeline with Relevance to the United States 1973 The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) was agreed on March 3, 1973 and the treaty became effective on July 1, 1975. • Bans international trade for primarily commercial purposes in species on Appendix I; international trade that is not for primarily commercial purposes may be allowed for specified other purposes that do not pertain to ivory trade. Trade in Appendix I specimens requires the importing country to issue a CITES import permit after making specified findings, and the exporting country to issue a CITES export permit after making specified findings. • Requires member countries to regulate international trade in species on Appendix II so as to ensure that such trade does not detrimentally affect the survival of the species. Trade in specimens of Appendix II species requires the exporting country to issue a CITES export permit after making specified findings. • Contains less stringent trade measures for “pre-Convention” wildlife, defined as acquired from the wild and possessed before the first date of listing of the species under CITES; international trade in pre-Convention specimens requires the issuance of a pre-Convention CITES certificate by the exporting country. The Asian elephant was listed on CITES Appendix I in 1975, and the African elephant listed on CITES Appendix III in 1976, Appendix II in 1977, then Appendix I in 1989. The Endangered Species Act (ESA) was signed into law on December 28, 1973 and became immediately effective. • Prohibits specified activities by individuals, organizations, and agencies subject to United States jurisdiction. -

THE IVORY TRADE of LAOS: NOW the FASTEST GROWING in the WORLD LUCY VIGNE and ESMOND MARTIN

THE IVORY TRADE OF LAOS: NOW THE FASTEST GROWING IN THE WORLD LUCY VIGNE and ESMOND MARTIN THE IVORY TRADE OF LAOS: NOW THE FASTEST GROWING IN THE WORLD LUCY VIGNE and ESMOND MARTIN SAVE THE ELEPHANTS PO Box 54667 Nairobi 00200 သࠥ ⦄ Kenya 2017 © Lucy Vigne and Esmond Martin, 2017 All rights reserved ISBN 978-9966-107-83-1 Front cover: In Laos, the capital Vientiane had the largest number of ivory items for sale. Title page: These pendants are typical of items preferred by Chinese buyers of ivory in Laos. Back cover: Vendors selling ivory in Laos usually did not appreciate the displays in their shops being photographed. Photographs: Lucy Vigne: Front cover, title page, pages 6, 8–23, 26–54, 56–68, 71–77, 80, back cover Esmond Martin: Page 24 Anonymous: Page 25 Published by: Save the Elephants, PO Box 54667, Nairobi 00200, Kenya Contents 07 Executive summary 09 Introduction to the ivory trade in Laos 09 History 11 Background 13 Legislation 15 Economy 17 Past studies 19 Methodology for fieldwork in late 2016 21 Results of the survey 21 Sources and wholesale prices of raw ivory in 2016 27 Ivory carving in 2016 33 Retail outlets selling worked ivory in late 2016 33 Vientiane 33 History and background 34 Retail outlets, ivory items for sale and prices 37 Customers and vendors 41 Dansavanh Nam Ngum Resort 41 History and background 42 Retail outlets, ivory items for sale and prices 43 Customers and vendors 44 Savannakhet 45 Ivory in Pakse 47 Luang Prabang 47 History and background 48 Retail outlets, ivory items for sale and prices 50 Customers -

CITES & Elephants

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service CITES & Elephants What is the “global ban” on ivory trade? A brief history of elephants and CITES trade in ivory, but allowed certain other CITES regulates the international activities. As such, the CITES “ban” on commercial and noncommercial ivory trade has several limitations: movement of both African and Asian elephants, including their ivory and ivory 1. It only applies to international products. The African elephant was first The elephant-shaped CITES logo was trade. CITES provisions apply to listed by Ghana in CITES Appendix III first used at CoP3 in 1981. The original the import, export, and re-export in 1976. The following year, at the first version, a simple black and white design, of listed species. Domestic markets meeting of the Conference of the Parties has since evolved to include species for ivory are governed by national (CoP1), African elephants were moved protected by CITES. or local laws. Under U.S. law, to Appendix II. In 1990, after nearly a commercial and non-commercial decade during which African elephant movement of ivory is additionally populations dropped by almost 50%, regulated by the African Elephant the species was moved to Appendix I Conservation Act (AfECA) and the of CITES. In 1997, some recovering Endangered Species Act (ESA). populations were moved back to Appendix II with strict limitations on 2. Hunting trophies are generally trade in ivory. exempt. Elephant range countries issue an annual export quota for Compared to African elephants, the hunting trophies taken for non- Asian elephant has had a simple history commercial purposes. -

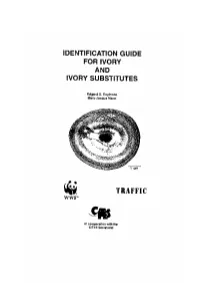

Ivory Identification: Introduction ______

Ivory identification: Introduction _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 WHAT IS IVORY? 3 THE IVORIES 9 Elephant and Mammoth 9 Walrus 13 Sperm Whale and Killer Whale 15 Narwhal 17 Hippopotamus 19 Wart Hog 21 IVORY SUBSTITUTES 23 NATURAL IVORY SUBSTITUTES 25 Bone 25 Shell 25 Helmeted Hornbill 26 Vegetable Ivory 27 MANUFACTURED IVORY SUBSTITUTES 29 APPENDIX 1 Procedure for the Preliminary Identification 31 of Ivory and Ivory Substitutes APPENDIX 2 List of Supplies and Equipment for Use in the 31 Preliminary Identification of Ivory and Ivory Substitutes GLOSSARY 33 SELECTED REFERENCES 35 COVER: An enhanced photocopy of the Schreger pattern in a cross-section of extant elephant ivory. A concave angle and a convex angle have been marked and the angle measurements are shown. For an explanation of the Schreger pattern and the method for measuring and interpreting Schreger angles, see pages 9 – 10. INTRODUCTION _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Ivory identification: Introduction Reprinted: 1999 Ivory identification: Introduction 3 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ The methods, data and background information on ivory identification compiled in this handbook are the result of forensic research conducted by the United States National Fish & Wildlife Forensics Laboratory, located in Ashland, Oregon. The goal of the research