Stony Brook University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subrosa Tactical Biopolitics

14 Common Knowledge and Political Love subRosa . the body has been for women in capitalist society what the factory has been for male waged workers: the primary ground of their exploitation and resistance, as the female body has been appropriated by the state and men, and forced to function as a means for the reproduction and accumulation of labor. Thus the importance which the body in all its aspects—maternity, childbirth, sexuality—has acquired in feminist theory and women’s history has not been misplaced. silvia federici (2004, p. 16) Under capitalism, femininity and gender roles became a “labor” function, and women became a “labor class.”1 On one hand, women’s bodies and labor are revered and exploited as a “natural” resource, a biocommons or commonwealth that is fundamental to maintain- ing and continuing life: women are equated with “the lands,” “mother-earth,” or “the homelands.”2 On the other hand, women’s sexual and reproductive labor—motherhood, pregnancy, childbirth—is economically devalued and socially degraded. In the Biotech Century, women’s bodies have become fl esh labs and Pharma-commons: They are mined for eggs, embryonic tissues, and stem cells for use in medical, and therapeutic experiments, and are employed as gestational wombs in assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Under such conditions, resistant feminist discourses of the “body” emerge as an explicitly biopolitical practice.3 subRosa is a cyberfeminist collective of cultural producers whose practice creates dis- course and experiential knowledge about the intersections of information and biotechnolo- gies in women’s lives, work, and bodies. Since the year 2000, subRosa has produced a variety of performances, participatory events, installations, publications, and Web sites as (cyber)feminist responses to key issues in bio- and digital technologies. -

Faith Ringgold the Studiowith and Quilts That Tell Stories ART HIST RY KIDS

Faith Ringgold The Studiowith and quilts that tell stories ART HIST RY KIDS THE GOLDEN AGE IN AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE Art is connected to everything... music, history, science, math, literature, and more! Let’s explore how this month‘s art relates to some of these subjects. What is the Harlem Renaissance? From the 1910’s - the 1930’s the northern Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem was booming with creativity. From fashion to food, music to dance, literature to art... amazing things were happening around every corner. This map illustrates the concentration of jazz clubs, restau- rants, and theaters in Harlem. As we spend this week connecting Faith Ringgold’s art to these other subjects, we’ll use her book, Harlem Renaissance Party, as our guide. Faith Ringgold’s book, Harlem Renaissance Party, takes us on a tour of the rich literary, culinary, musical, and theatrical scene in Harlem during the 1930’s. The following pages explore the Harlem Renaissance as Ringgold describes it in her book (and she should know, because she was actually there!) Click the image above to see a story time reading of the book! Illustration by Elmer Simms Campbell | Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library February 2019 | Week 3 1 Faith Ringgold The Studiowith and quilts that tell stories ART HIST RY KIDS CONNECTING THE DOTS Geography The United States of America Here are maps of The United States of America, New York state, and Harlem – a neighborhood in the Manhattan borough of New New York State York City. February 2019 | Week 3 2 Faith Ringgold The Studiowith and quilts that tell stories ART HIST RY KIDS CONNECTING THE DOTS Literature - Poetry + Folk Tales Langston Hughes Zora Neale Hurston 1936 photo by Carl Van Vechten Langston Hughes was one of the strongest Zora Neale Hurston wrote Mules and Men – literary voices during the Harlem Renaissance. -

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

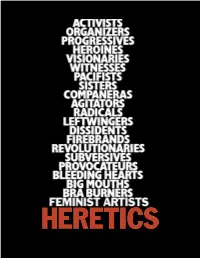

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Aca Galleriesest. 1932

EST. 1932 ACA GALLERIES Faith Ringgold Courtesy of ACA Galleries Faith Ringgold, American People Series #19: U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power, 1967 th ACA GALLERIES 529 West 20 Street New York, NY 10011 | t: 212-206-8080 | e: [email protected] | acagalleries.com EST. 1932 ACA GALLERIES The Enduring Power of Faith Ringgold’s Art By Artsy Editors Aug 4, 2016 4:57 pm Portrait of Faith Ringgold. Photo by Grace Matthews. In 1967, a year of widespread race riots in America, Faith Ringgold painted a 12-foot-long canvas called American People Series #20: Die. The work shows a tumult of figures, both black and white, wielding weapons and spattered with blood. It was a watershed year for Ringgold, who, after struggling for a decade against the marginalization she faced as a black female artist, unveiled the monumental piece in her first solo exhibition at New York’s Spectrum Gallery. Earlier this year, several months after Ringgold turned 85, the painting was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art, cementing her legacy as a pioneering artist and activist whose work remains searingly relevant. Where did she come from? Ringgold was born in Harlem in 1930. Her family included educators and creatives, and she grew up surrounded by the Harlem Renaissance. The street where she was raised was also home to influential activists, writers, and artists of the era—Thurgood Marshall, W.E.B. Dubois, and Aaron Douglas, to name a few. “It’s nice th ACA GALLERIES 529 West 20 Street New York, NY 10011 | t: 212-206-8080 | e: [email protected] | acagalleries.com EST. -

Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive

Article Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive Kathy Carbone ABSTRACT The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The CalArts Feminist Art Program (1971–1975) played an influential role in this movement and today, traces of the Feminist Art Program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection. Through a series of short interrelated archives stories, this paper explores some of the ways in which women responded to and engaged the Collection, especially a series of letters, for feminist projects at CalArts and the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths, University of London over the period of one year (2017–2018). The paper contemplates the archive as a conduit and locus for current day feminist identifications, meaning- making, exchange, and resistance and argues that activating and sharing—caring for—the archive’s feminist art histories is a crucial thing to be done: it is feminism-in-action that not only keeps this work on the table but it can also give strength and definition to being a feminist and an artist. Carbone, Kathy. “Dear Sister Artist,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo- Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3. ISSN: 2572-1364 INTRODUCTION The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Feminist Art Program, which ran from 1971 through 1975, played an influential role in this movement and today, traces and remains of this pioneering program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection (henceforth the “Collection”). -

REWIND a Guide to Surveying the First Decade: Video Art and Alternative Media in the U.S., 1968-1980

REWIND A Guide to Surveying the First Decade: Video Art and Alternative Media in the U.S., 1968-1980 REWIND A Guide to Surveying the First Decade: Video Art and Alternative Media in the U.S., 1968-1980 REWIND 1995 edition Editor: Chris Hill Contributing Editors: Kate Horsfield, Maria Troy Consulting Editor: Deirdre Boyle REWIND 2008 edition Editors: Abina Manning, Brigid Reagan Design: Hans Sundquist Surveying the First Decade: Video Art and Alternative Media in the U.S., 1968–1980 1995 VHS edition Producer: Kate Horsfield Curator: Chris Hill Project Coordinator: Maria Troy Produced by the Video Data Bank in collaboration with Electronic Arts Intermix and Bay Area Video Coalition. Consultants to the project: Deirdre Boyle, Doug Hall, Ulysses Jenkins, Barbara London, Ken Marsh, Leann Mella, Martha Rosler, Steina Vasulka, Lori Zippay. On-Line Editor/BAVC: Heather Weaver Editing Facility: Bay Area Video Coalition Opening & Closing Sequences and On-Screen Titles: Cary Stauffacher, Media Process Group Preservation of Tapes: Bay Area Video Coalition Preservation Supervisor: Grace Lan, Daniel Huertas Special thanks: David Azarch, Sally Berger, Peer Bode, Pia Cseri-Briones, Tony Conrad, Margaret Cooper, Bob Devine, Julia Dzwonkoski, Ned Erwin, Sally Jo Fifer, Elliot Glass, DeeDee Halleck, Luke Hones, Kathy Rae Huffman, David Jensen, Phil Jones, Lillian Katz, Carole Ann Klonarides, Chip Lord, Nell Lundy, Margaret Mahoney, Marie Nesthus, Gerry O’Grady, Steve Seid, David Shulman, Debbie Silverfine, Mary Smith, Elisabeth Subrin, Parry Teasdale, Keiko -

“My Personal Is Not Political?” a Dialogue on Art, Feminism and Pedagogy

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, July 2009 “My Personal Is Not Political?” A Dialogue on Art, Feminism and Pedagogy Irina Aristarkhova and Faith Wilding This is a dialogue between two scholars who discuss art, feminism, and pedagogy. While Irina Aristarkhova proposes “active distancing” and “strategic withdrawal of personal politics” as two performative strategies to deal with various stereotypes of women's art among students, Faith Wilding responds with an overview of art school’s curricular within a wider context of Feminist Art Movement and the radical questioning of art and pedagogy that the movement represents Using a concrete situation of teaching a women’s art class within an art school environment, this dialogue between Faith Wilding and Irina Aristakhova analyzes the challenges that such teaching represents within a wider cultural and historical context of women, art, and feminist performance pedagogy. Faith Wilding has been a prominent figure in the feminist art movement from the early 1970s, as a member of the California Arts Institute’s Feminist Art Program, Womanhouse, and in the recent decade, a member of the SubRosa, a cyberfeminist art collective. Irina Aristarkhova, is coming from a different history to this conversation: generationally, politically and theoretically, she faces her position as being an outsider to these mostly North American and, to a lesser extent, Western European developments. The authors see their on-going dialogue of different experiences and ideas within feminism(s) as an opportunity to share strategies and knowledges towards a common goal of sustaining heterogeneity in a pedagogical setting. First, this conversation focuses on the performance of feminist pedagogy in relation to women’s art. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

A Current Listing of Contents

WOMEN'S STUDIES LIBRARIAN EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS VOLUME 16, NUMBER 2 SUMMER 1996 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard Women's Studies Librarian University of Wisconsin System 430 Memorial Library / 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608) 263-5754 EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS Volume 16, Number 2 Summer 1996 Periodical literature is the culling edge ofwomen's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table ofcontents pages from current issues ofmajor feministjournals are reproduced in each issue ofFeminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. U.S. subscription price(s). -

Hauser & Wirth Announces Major Initiative to Raise Funds for Key

Press Release Hauser & Wirth Announces Major Initiative to Raise Funds for Key Visual Arts Organizations in New York City Impacted by the COVID-19 Pandemic Beginning early October, works by scores of artists will be sold to benefit 16 non-profit institutions and charitable partners New York…Hauser & Wirth co-presidents Iwan Wirth, Manuela Wirth, and Marc Payot, announced today that the gallery has organized ‘Artists for New York,’ a major initiative to raise funds in support of a group of pioneering non-profit visual arts organizations across New York City that have been profoundly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The project brings together dozens of works committed by foremost artists across generations, from both within and outside of the gallery’s program, that will be sold to benefit these institutions that have played a significant role in shaping the city’s rich cultural history and will play a critical role in its future recovery. The coronavirus pandemic has taken an unprecedented toll upon the arts in New York. Facing dire budget shortfalls for the 2020 fiscal year caused by necessary and prolonged closures during the pandemic, and expecting further impact upon earned income and contributed revenue in the year ahead, the city’s small and mid-scale institutions are extremely vulnerable at this moment. ‘Artists for New York’ will raise funds to support the recovery needs of fourteen of these organizations: Artists Space, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Dia Art Foundation, The Drawing Center, El Museo del Barrio, High Line Art, MoMA PS1, New Museum, Public Art Fund, Queens Museum, SculptureCenter, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Swiss Institute, and White Columns.