Snag Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hyalophora Cecropia): Morphological, Behavioral, and Biophysical Differences

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS Neurobiology Publications and Presentations Neurobiology 2017-03-22 Dimorphic cocoons of the cecropia moth (Hyalophora cecropia): Morphological, behavioral, and biophysical differences Patrick A. Guerra University of Massachusetts Medical School Et al. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/neurobiology_pp Part of the Neuroscience and Neurobiology Commons Repository Citation Guerra PA, Reppert SM. (2017). Dimorphic cocoons of the cecropia moth (Hyalophora cecropia): Morphological, behavioral, and biophysical differences. Neurobiology Publications and Presentations. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174023. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/ neurobiology_pp/207 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Neurobiology Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESEARCH ARTICLE Dimorphic cocoons of the cecropia moth (Hyalophora cecropia): Morphological, behavioral, and biophysical differences Patrick A. Guerra¤*, Steven M. Reppert* Department of Neurobiology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Massachusetts, United States of America ¤ Current address: Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cincinnati, -

Samia Cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- Place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates

________________________________________________________________________________________ Volume 61, Number 4 Winter 2019 www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________________________________________ Inside: Butterflies of Papua Southern Pearly Eyes in exotic Louisiana venue Philippine butterflies and moths: a new website The Lepidopterists’ Society collecting statement updated Lep Soc, Southern Lep Soc, and Assoc of Trop Lep combined meeting Butterfly vicariance in southeast Asia Samia cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates ... and more! ________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ Contents www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________ Digital Collecting -- Butterflies of Papua, Indonesia ____________________________________ Bill Berthet. .......................................................................................... 159 Volume 61, Number 4 Butterfly vicariance in Southeast Asia Winter 2019 John Grehan. ........................................................................................ 168 Metamorphosis. ....................................................................................... 171 The Lepidopterists’ Society is a non-profit ed- Membership Updates. ucational and scientific organization. The ob- Chris Grinter. ....................................................................................... 171 -

![Abt]Ndaiyce in Norih.Easiern Botswaiva. By](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2939/abt-ndaiyce-in-norih-easiern-botswaiva-by-1002939.webp)

Abt]Ndaiyce in Norih.Easiern Botswaiva. By

THE NATIIRAL HISTORY Oß Imbrøsíø belína (lVestwood) (LEPIDOPTERA: SATIIRIUDAE), AND SOME Ì'ACTORS AFT'ECTING ITS ABT]NDAIYCE IN NORIH.EASIERN BOTSWAIVA. BY MARKS K. DITLHOCIO A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department ofZoology Universþ ofManitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba (c) January, 1996 \flonarLibrarv Bibliothèque nationale l*l du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographic Services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) K1A ON4 K1A ON4 Yout l¡le Volrc élércnce Ou l¡le Nolrc rélérence The author has granted an L'auteur a accordé une licence irrevocable non-exclus¡ve licence irrévocable et non exclus¡ve allowing the National Library of permettant à la Bibliothèque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell cop¡es of reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa thèse in any form or format, making de quelque manière et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette thèse à la disposition des person nes intéressées. The author retains ownership of L'auteur conserve la propriété du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qu¡ protège sa Neither the thesis nor substantial thèse. Ni la thèse ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent être imprimés ou his/her perm¡ss¡on. autrement reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Insect Immunity

INSECT IMMUNITY: INDUCIBLE ANTIBACTERIAL PROTEINS FROM HYALOPHORA CECROPIA Dan Hultmark University of Stockholm Dept. of Microbiology S-106 91 Stockholm Sweden INSECT IMMUNITY: INDUCIBLE ANTIBACTERIAL PROTEINS FROM HYALOPHORA CECROPIA Dan Hultmark Stockholm 1982 Doctoral Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Stockholm 1982 This thesis is based on five papers; references (1-5) in the reference list. ABSTRACT - A powerful bactericidal activity can be induced in the hemolymph of many insects as a response to an injection of bacteria. The nature of the effector molecules of this immune response was investigated, using pupae of the Cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia. Three major types of antibacterial proteins were found: the cecropins, the P5 proteins, and lysozyme. They appear in the hemolymph as a result of de novo synthesis. Six different cecropins were purified and characterized. The full amino acid sequences of the three major cecropins A, B and D were determined, as well as partial sequences of the three minor cecropins C, E and F. The cecropins are all very small (M = 4,000) and basic (pi > 9.5) proteins, and they show extensive homology in the if sequences. The three major cecropins are products of different genes. Their C-terminals are blocked by uncharged groups, which can be removed by mild acid hydrolysis. The minor cecropins are closely related to the major forms, and may be unblocked precursors or, in one case (cecropin F), a minor allelic form. The cecropins were shown to be lytic, and to be efficient against several Gram positive and Gram negative bacterial strains, but not against mammalian cells. -

Cecropia Moth, Cecropia Silk Moth, Robin Moth, Hyalophora Cecropia Linnaeus (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae: Attacini)1 Geoffrey R

EENY 478 Cecropia Moth, Cecropia Silk Moth, Robin Moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae: Attacini)1 Geoffrey R. Gallice2 Introduction The cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus, is among the most spectacular of the North American Lepidoptera. It is a member of the Saturniidae, a family of moths prized by collectors and nature lovers alike for their large size and extremely showy appearance. Adults are occasionally seen attracted to lights during spring and early summer, a common habit of many moths. It is unclear exactly why these insects visit lights, although a number of theories exist. One such theory posits that artificial lights interfere with the moths’ internal Figure 1. Adult female cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus, navigational equipment. Moths, and indeed many other laying eggs on host plant. Credits: David Britton. Used with permission. night-flying insects, use light from the moon to find their way in the dark of night. Since the moon is effectively cecropia (Linnaeus, 1758) at optical infinity, its distant rays enter the moth’s eye in diana (Castiglioni, 1790) parallel, making it an extremely useful navigational tool. A macula (Reiff, 1911) moth is confused as it approaches an artificial point source uhlerii (Polacek, 1928) of light, such as a street lamp, and may often fly in circles in obscura (Sageder, 1933) a constant attempt to maintain a direct flight path. albofasciata (Sageder, 1933) (from Heppner 2003) Synonymy Hyalophora Duncan, 1841 Distribution Samia. - auct. (not Hübner, [1819]) The range of Hyalophora cecropia is from Nova Scotia in Platyysamia Grote, 1865 eastern Canada and Maine, south to Florida, and west to the Canadian and U.S. -

Polyphemus Moth Antheraea Polyphemus (Cramer) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae)1 Donald W

EENY-531 Polyphemus Moth Antheraea polyphemus (Cramer) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae)1 Donald W. Hall2 The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of amateur enthusiasts and also have been used for numerous insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant physiological studies—particularly for studies on molecular to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested mechanisms of sex pheromone action. laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences. Distribution Polyphemus moths are our most widely distributed large Introduction silk moths. They are found from southern Canada down The polyphemus moth, Antheraea polyphemus (Cramer), into Mexico and in all of the lower 48 states, except for is one of our largest and most beautiful silk moths. It is Arizona and Nevada (Tuskes et al. 1996). named after Polyphemus, the giant cyclops from Greek mythology who had a single large, round eye in the middle Description of his forehead (Himmelman 2002). The name is because of the large eyespots in the middle of the moth is hind wings. Adults The polyphemus moth also has been known by the genus The adult wingspan is 10 to 15 cm (approximately 4 to name Telea, but it and the Old World species in the genus 6 inches) (Covell 2005). The upper surface of the wings Antheraea are not considered to be sufficiently different to is various shades of reddish brown, gray, light brown, or warrant different generic names. Because the name Anther- yellow-brown with transparent eyespots. There is consider- aea has been used more often in the literature, Ferguson able variation in color of the wings even in specimens from (1972) recommended using that name rather than Telea the same locality (Holland 1968). -

Recent Records for Parasitism in Saturniidae (Lepidoptera)

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nachrichten des Entomologischen Vereins Apollo Jahr/Year: 1984 Band/Volume: 5 Autor(en)/Author(s): Peigler Richard S. Artikel/Article: Recent records for parasitism in Saturniidae 95-105 ©Entomologischer Verein Apollo e.V. Frankfurt am Main; download unter www.zobodat.at Nachr. ent. Ver. Apollo, Frankfurt, N. F., Bd. 5, Heft 4: 95—105 — März 1985 95 Recent records for parasitism in Saturniidae (Lepidoptera) by RICHARD S. PEIGLER Abstract: Numerous records of parasites reared from Saturniidae are given, several of which are previously unpublished host-parasite associations. Records are from several regions of the U.S.A. and Central America, with a few from Hong Kong and one from France. Parasites reported here belong to the dipterous family Tachinidae and the hymenopterous families Ichneumonidae, Braconidae, Chalcididae, Perilampidae, Torymidae, Eupel- midae, and Eulophidae. Neuere Beobachtungen über Parasitismus bei Saturniidae (Lepidoptera) Zusammenfassung:Es werden verschiedene Beobachtungen über Parasiten, die aus Saturniiden gezüchtet wurden, gegeben, von denen einige bisher noch unbekannte Wirt-Parasit-Beziehungen darstellen. Die Beobachtungen stammen aus verschiedenen Regionen der USA und Zentralamerikas, einige aus Hongkong und eine aus Frankreich. Die hier genannten Parasiten gehören zu der Dipterenfamilie Tachinidae und den Hymenopterenfa- milien Ichneumonidae, Braconidae, Chalcididae, Perilampidae, Torymidae, Eupelmidae und Eulophidae. Insbesondere wird auf die Notwendigkeit, alle erreichbaren Nachweise von Parasitismus bei Schmetterlingslarven zu dokumentieren und die Parasiten von entsprechenden Fachleuten bestimmen zu lassen, hingewiesen. Sorgfäl tige Zuchtarbeit ist nötig, um einwandfreie Zuordnung der Parasiten zu ihrem jeweiligen Wirt zu ermöglichen; am besten eignet sich hierfür die Einzelhaltung parasitismusverdächtigter Larven. -

1 Toward a Metabolic Theory of Life History 1 2 Joseph Robert Burgera

1 Toward a metabolic theory of life history 2 3 Joseph Robert Burgera,1*, Chen Houb,1 and James H. Brownc,1 4 a Duke University Population Research Institute, Durham, NC 27705; 5 [email protected] 6 b Department of Biological Science, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO 7 65409; 8 [email protected] 9 c Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; 10 [email protected] 11 1All authors contributed equally 12 *Present address: Institute of the Environment, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 13 Corresponding authors: JRB [email protected]; JHB [email protected] 14 15 Significance 16 Data and theory reveal how organisms allocate metabolic energy to components of the life 17 history that determine fitness. In each generation animals take up biomass energy from the 18 environment and expended it on survival, growth, and reproduction. Life histories of animals 19 exhibit enormous diversity – from large fish and invertebrates that produce literally millions of 20 tiny eggs and suffer enormous mortality, to mammals and birds that produce a few large 21 offspring with much lower mortality. Yet, underlying this enormous diversity, are general life 22 history rules and tradeoffs due to universal biophysical constraints on the channels of selection. 23 These rules are characterized by general equations that underscore the unity of life. 24 25 Abstract 26 The life histories of animals reflect the allocation of metabolic energy to traits that determine 27 fitness and the pace of living. Here we extend metabolic theories to address how demography 28 and mass-energy balance constrain allocation of biomass to survival, growth, and reproduction 29 over a life cycle of one generation. -

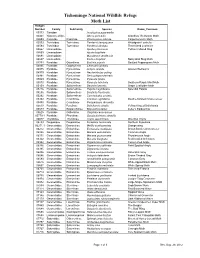

Tishomingo NWR Moth List

Tishomingo National Wildlife Refuge Moth List Hodges Number Family SubFamily Species Name_Common 00373 Tineidae Acrolophus popeanella 02401 Yponomeutidae Atteva punctella Ailanthus Webworm Moth 02693 Cossidae Cossinae Prionoxystus robinae Carpenterworm Moth 03593 Tortricidae Tortricinae Pandemis lamprosana Woodgrain Leafroller 03594 Tortricidae Tortricinae Pandemis limitata Three-lined Leafroller 04667 Limacodidae Apoda y-inversum Yellow-Collared Slug 04669 Limacodidae Apoda biguttata 04691 Limacodidae Monoleuca semifascia 04697 Limacodidae Euclea delphinii Spiny Oak Slug Moth 04794 Pyralidae Odontiinae Eustixia pupula Spotted Peppergrass Moth 04895 Pyralidae Glaphyriinae Chalcoela iphitalis 04975 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Achyra rantalis Garden Webworm 04979 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Neohelvibotys polingi 04991 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Sericoplaga externalis 05069 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Pyrausta tyralis 05070 Pyralidae Pyraustinae Pyrausta laticlavia Southern Purple Mint Moth 05159 Pyralidae Spilomelinae Desmia funeralis Grape Leaffolder Moth 05226 Pyralidae Spilomelinae Palpita magniferalis Splendid Palpita 05256 Pyralidae Spilomelinae Diastictis fracturalis 05292 Pyralidae Spilomelinae Conchylodes ovulalis 05362 Pyralidae Crambinae Crambus agitatellus Double-banded Grass-veneer 05450 Pyralidae Crambinae Parapediasia decorella 05533 Pyralidae Pyralinae Dolichomia olinalis Yellow-fringed Dolichomia 05579 Pyralidae Epipaschiinae Epipaschia zelleri Zeller's Epipaschia 05625 Pyralidae Galleriinae Omphalocera cariosa 05779.1 Pyralidae Phycitinae Quasisalebriaria -

Activity Patterns and Energetics of the Moth, Hyalophora Cecropia

jf. Exp. Biol. (1970), 53, 611-627 6ll With 1 plate and 7 text-figures Printed in Great Britain ACTIVITY PATTERNS AND ENERGETICS OF THE MOTH, HYALOPHORA CECROPIA BY JAMES L. HANEGAN AND JAMES EDWARD HEATH Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801 (Received 1 June 1970) INTRODUCTION The metabolic rate and fuel consumption of flying insects have been previously reported (Sotavalta & Lavlajainen, 1969; Zebe, 1954; Weis-Fogh, 1952; and others). The experiments of these workers were based on tethered insects flown to exhaustion on a known amount of fuel previously imbibed by the insect. The metabolic cost of flight over an insect's life span or the percentage of the total metabolism devoted to flight has not been reported. The moth, Hyalophora cecropia, is ideally suited for an analysis of the energetics of flight. These heavy-bodied moths do not feed as adults (Rau, 1910) and both the substrate for flight muscle metabolism and the total energy reserve have been deter- mined by Domroese & Gilbert (1964). They have a short adult life, averaging 1 week, and their activity can be monitored continuously. For an analysis of the energetics of H. cecropia over its adult life the only variables that must be determined are the metabolic rate during various phases of activity and the total duration of flight. Thoracic temperature of H. cecropia has been correlated with activity (Hanegan & Heath, 1970). When the body temperature equals the air temperature the animal is inactive. Upon initiation of activity the thoracic temperature rises linearly to a precise temperature. -

American Prairie Bioblitz Report (2011)

2011 FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 WHAT IS BIOBLITZ? 3 HISTORY OF BIOBLITZ 4 FIELD BIOLOGISTS AND TAXONOMISTS 5 SUPPORT FOR THE PROJECT 6 SURVER LOCATIONS 7 TAXONOMIC GROUP RESULTS 8 HYMENOPTERA 8 LEPIDOPTERA 9 COLEOPTERA 9 ORTHOPTERA, HEMIPTERA AND ARANEAE 9 DIPTERA AND STREPSIPTERA 10 AQUATIC INVERTEBRATES 10 EARTHWORMS 11 LICHEN 11 FUNGI 12 VASCULAR PLANTS 14 HERPETOFAUNA 14 FISH 15 TERRESTRIAL MAMMALS 16 BATS 17 BIRDS 18 2011 BIOBLITZ CLOSING STATEMENT 19 SPECIES LIST 20 2011 FINAL REPORT Compiled by: Kayhan Ostovar 3 INTRODUCTION On June 23-25, 2011, the American Prairie Reserve held their first BioBlitz. In just 24 hours a list of 550 species was created by approximately 70 scientists, college students, citizen scien- tists and volunteers. The number of documented species was only limited by the number of taxonomic experts we could get to join this project in such a remote location. The species list will serve as a benchmark of the biodiversity in the early years on the Reserve. Grassland ecosystems are surprisingly one of the most endan- gered systems on the planet. As more land is added to the Reserve network, bison populations grow, and habitat restora- tion is continued, we expect to see species composition and diversity change over time. This landmark event was organized in order to raise awareness of the efforts being made to restore America’s prairies, create educational opportunities and to gather baseline species data. WHAT IS A BIOBLITZ? Biodiversity is often something we think about when we discuss tropical rainforests. However, there is tremendous diversity on prairie landscapes even though it may not be visible at first glance. -

Glover's Silkmoth, Hyawphora Gwveri (Strecker)(Lepidoptera: Saturniidae), New to British Columbia

1. ENrOMOL Soc. BRIT. COLUMBIA 86 (1989), SEPT. 3D, 1989 89 GLOVER'S SILKMOTH, HYAWPHORA GWVERI (STRECKER)(LEPIDOPTERA: SATURNIIDAE), NEW TO BRITISH COLUMBIA ROBERT A. CANNINGS AND C.S. GUppy ROYAL BRITISH COLUMBIA MUSEUM 675 BELLEVILLE STREET VICfORIA, B.C. V8V lX4 Two rather common species of giant silkrnoths of the subfamily Satumiinae (Lepidoptera: Satumiidae) occur in southern British Columbia. Both species, the Polyphemus Moth (Antheraea polyphemus [Cramer]) and the Ceanothus Silkrnoth (Hyalophora euryalis [Bois duvall) are large and spectacular, and evoke comment from anyone who sees them. Both range northwards to at least the central Cariboo region. Three other striking species of the subfamily occur in the Peace River district of Alberta, but these moths, the Cecropia Moth (Hyalophora cecropia [Linnaeus]), the Columbia Silkmoth (H. columbia [S.L Smith]), and Glover's Silkrnoth (H. gloveri [Strecker l) have never been reported from British Columbia. Therefore, it was a surprise when a specimen of H. gloveri was recently captured and sent to us from the Peace River district of the province. A female H. gloveri (Fig. 1) was discovered by Carolyn and TeITY Wood and their family on the northeast shore of Charlie Lake near Fort St. John. The moth was clinging to a branch of a small aspen tree (Populus tremuloides Michx.) about 2.5 m from the water's edge on 22 May 1989 at 20:00 h (MDD. The moth's wings were expanded, but the insect had evidently only recently emerged; there were fluid stains on the branch below the moth and its red colour faded to brown as it dried.