Issues for the Acrel Ilsa Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contiguous Residential Land FAQ

Contiguous Residential Land FAQ What is the difference between Vacant Land and contiguous Residential Land? Vacant Land is any parcel of land that does not have a building or residence built on it (unimproved) as of the Assessment Date- January, 1st each year. Vacant Land is Assessed at 29% of its Actual Value. Contiguous Residential Land is also unimproved but is contiguous to a residentially improved parcel. Residential Land is Assessed at the Residential rate of 7.15% of its Actual Value. How does land qualify as contiguous Residential Land? For Vacant Land to be classified as Residential Land, it needs to have a residential dwelling on it, or it must meet all three of the following criteria, as established by law; 1. The Vacant Land parcel must be contiguous with the Residentially improved parcel. 2. Both parcels must be under common ownership (identical). 3. Both parcels must be used as a unit. What does “contiguous” mean? For property classification and taxation purposes, “contiguous” means parcels of land that physically touch one another. This meaning was affirmed in Mooks v. Board of County Commissioners, 2020 CO 12, by the Colorado Supreme Court. What does “common ownership” mean? Simply put, “common ownership” means that both the residentially improved parcel and the contiguous vacant land parcel must have identical ownership, established by the County’s recorded documents. This meaning was affirmed in Lannie v. Board of County Commissioners, 2020 COA 77, by the Colorado Court of Appeals. What does “used as a unit” mean? In Hogan v. Board of County Commissioners, 2020 CO 12, the Colorado Supreme Court stated, “that a landowner must use multiple parcels of land together as a collective unit of residential property to satisfy the ‘used as a unit’ requirement.” Put another way, all contiguous properties must be used residentially and as though they are a greater, single parcel of land. -

Mls Glossary of Terms

MLS GLOSSARY OF TERMS A Acceptance - The time at which an offer to purchase is accepted. The fact that it was accepted must be relayed to the person that made an offer for all parties to be bound to the contract. Acres - The total number of acres of the property. Acres Cultivated – (of land or fields) Prepared for raising crops by plowing or fertilizing. Acres Pasture – This type of land is typically used by animals. Acres Timber – Trees or wooded land considered as a source of wood. Ad Valorem Tax – Charged by local government, this tax is based on the value of the property, as determined by the local government authorities. Additional Deposit – A buyer of real property will generally give a small deposit with an offer, and a more substantial deposit after the offer has been accepted. The second deposit is the "additional deposit." Additional Public Remarks – "The additional remarks shall not include any contact information i.e. agent, broker, company, bonuses, commission, URL information, affiliated businesses and owner name, phone numbers, however this information may be entered in the Realtor Remarks field". Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM) - A mortgage whose interest rate over the life of the loan is not necessarily the same as the original interest rate at the loan inception. Rate changes may go up or down and are usually tied to an economic indicator and a time. The person getting the mortgage should check to see if these fluctuations have a cap, and make sure they are comfortable with whatever that cap is. Some ARMS are convertible to a fixed interest rate after a period. -

Article 5 – General Provisions

Cherokee County Zoning Ordinance Article 5 – General Provisions Article 5 – General Provisions 5.1 Interpretation. 5.1-1 In their interpretation and application, the provisions of the Zoning Ordinance shall be held to be the minimum requirements for the promotion of the public health, safety, morals and welfare, including those purposes, intents, objectives or similar language as set out in various Articles of the Ordinance. 5.1-2 Where the conditions imposed by any provision of this zoning code upon the use of land or buildings or upon the bulk of buildings are either more restrictive or less restrictive than comparable conditions imposed by any other provisions of this code or of any other law, Ordinance, resolution, rule or regulation of any land, the regulations which are more restrictive (or which impose higher standards or requirements) shall govern. 5.2 Scope of Regulations. Except as otherwise provided in Article 14, “Non-Conforming Uses”, all buildings erected hereafter, all uses of land or buildings established hereafter, all structural alteration or relocation of existing buildings occurring hereafter, and all enlargements of or additions to existing uses occurring hereafter shall be subject to all regulations of this Ordinance which are applicable to the zoning districts in which such buildings, uses or land shall be located. 5.3 Building Permits. Building permits are required for all structures erected, converted, enlarged, restructured, moved or structurally altered and the provisions for said building permit shall be separately -

Publication 577 Faqs Regarding the Additional Tax on Transfers of Residential Real Property for $1 Million Or More

Publication 577 FAQs Regarding the Additional Tax on Transfers of Residential Real Property for $1 Million or More Pub 577 (2/10) Publication 577 (2/10) Table of contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 5 Definitions................................................................................................................................................... 5 Frequently asked questions......................................................................................................................... 7 NOTE: A Publication is an informational document that addresses a particular topic of interest to taxpayers. Subsequent changes in the law or regulations, judicial decisions, Tax Appeals Tribunal decisions, or changes in Department policies could affect the validity of the information contained in a publication. Publications are updated regularly and are accurate on the date issued. This page intentionally left blank Publication 577 (2/10) Introduction Tax Law Article 31 imposes a real estate transfer tax on each conveyance of real property, or interest in real property, when the consideration exceeds $500. The tax is computed at a rate of two dollars for each $500 of consideration, or for any fractional part of $500. An additional tax is imposed on each conveyance of real property or interest in real property used in whole or in part as a personal residence when the consideration for the entire conveyance -

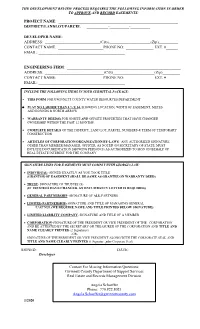

Easement Procedures and Forms Package (PDF)

THE DEVELOPMENT REVIEW PROCESS REQUIRES THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION IN ORDER TO APPROVE AND RECORD EASEMENTS: PROJECT NAME: _____________________________________________________________ DISTRICT/LANDLOT/PARCEL ___________-__________-__________ DEVELOPER NAME: __________________________________________________________ ADDRESS: ____________________________(City)_____________________(Zip)__________ CONTACT NAME: _______________________PHONE NO: ______________ EXT. #______ EMAIL: ____________________________________________ ENGINEERING FIRM: __________________________________________________________ ADDRESS: ______________________________(City)_____________________(Zip)_________ CONTACT NAME: _______________________PHONE NO: ______________ EXT. #_______ EMAIL: ____________________________________________ INCLUDE THE FOLLOWING ITEMS IN YOUR SUBMITTAL PACKAGE: THIS FORM FOR GWINNETT COUNTY WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT PLAT NO LARGER THAN 8 ½ X 14, SHOWING LOCATION, WIDTH OF EASEMENT, METES AND BOUNDS & NORTH ARROW WARRANTY DEED(S) FOR ONSITE AND OFFSITE PROPERTIES THAT HAVE CHANGED OWNERSHIP WITHIN THE PAST 12 MONTHS. COMPLETE DETAILS OF THE DISTRICT, LAND LOT, PARCEL NUMBERS & TERM OF TEMPORARY CONSTRUCTION ARTICLES OF CORPORATION/ORGANIZATION/BY-LAWS: ANY AUTHORIZED SIGNATURE OTHER THAN MEMBER/MANAGER, OFFICER, AS NOTED ON SECRETARY OF STATE, MUST INCLUDE DOCUMENTATION SHOWING PERSON(S) AS AUTHORIZED TO SIGN ON BEHALF OF REAL ESTATE INTEREST FOR THE COMPANY. SIGNATURE LINES FOR EASEMENTS MUST COMPLY WITH GEORGIA LAW: INDIVIDUAL- SIGNED EXACTLY -

The Effects of Land Value Taxation in a Computable General Equilibrium Model *

The Effects of Land Value Taxation in a Computable General Equilibrium Model * Alex Anas Department of Economics State University of New York at Buffalo Amherst, New York 14260 [email protected] © 2014 Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper *The findings and conclusions of this Working Paper reflect the views of the author(s) and have not been subject to a detailed review by the staff of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Contact the Lincoln Institute with questions or requests for permission to reprint this paper. [email protected] Lincoln Institute Product Code: WP14AA1 Abstract The paper reports on the application to land taxation, of the RELU-TRAN model, a spatially detailed general equilibrium model of a regional economy that treats labor and building markets, production of goods and services and real estate development. The model is used to investigate the efficiency gains that can be obtained by switching from the conventional ad-valorem property tax (CPT) to a uniform ad-valorem land tax (ULT) on residual imputed land value. The ULT is not a perfectly neutral tax but it has the advantage that it is relatively easily implementable and the fact that it is proportional to imputed land value, makes the ULT fair and defensible. The simulations are done by using the Los Angeles version of RELU-TRAN, calibrated for the year 2000. Three types of tax switches are evaluated. In the first, the CPT revenue is fully replaced by the ULT revenue and higher levels of the ULT are examined. In the second and third simulations the ULT is used in place of the CPT. -

Vacant Land/Lot Purchase Contract by Scott M

AZQ_February_2013_Final_Layout 1 2/28/2013 6:16 PM Page 1 SPRING 2013 ® YOUR GUIDE TO THE 2013 VACANT LAND/LOT PURCHASE CONTRACT Page 2 AZQ_February_2013_Final_Layout 1 2/28/2013 6:16 PM Page 2 2 A MESSAGE FROM 2013 AAR PRESIDENT SUE FLUCKE March in Arizona is one of the best times of year, the weather is beautiful and the housing market is typically still at its busiest. This year, we’ve seen the market pick back up again with foreclosures and REOs stabilizing, short-sales getting a bit easier and even a slight uptick in housing prices. I know we’re all keeping very busy! As we look to the second quarter of 2013, I want to remind you of my theme for this year: Exceeding Expectations. This could be with your clients, by taking extra special care to properly review all aspects of the transaction. This could also be with your colleagues, by lending a helping hand when needed or even just offering a second set of eyes – it really makes a difference. Or, this could even be with yourself, by setting a goal to receive a new designation or increase your professional network. The good news is the latter can be Sue Flucke, CRB, GRI, rCRMS 2013 AAR President taken care of all in one week, if you join AAR at the 2013 Spring Convention, April 7-11 in Tucson. This event takes the place of AAR’s Winter Conference and will be bigger and better than ever. The full schedule is located here: www.aaronline.com/SpringConvention Reminding ourselves to exceed expectations is a great way to keep us all ahead in the game. -

UDO Title 2: Land Use and Zoning

Title 2: Land Use and Zoning Chapter 200. General Provisions. Section 200-10. Purpose. This Title 2 is intended to implement the purposes set forth in Section 100-20, and further is enacted for the purposes of promoting the health, safety, morals, convenience, order, prosperity and the general welfare of the present and future inhabitants of Gwinnett County; of lessening congestion in the streets; securing safety from fire, panic and other dangers; providing adequate light and air; preventing the overcrowding of land, avoiding both undue concentration of population and urban sprawl; facilitating the adequate provision of transportation, water, sewerage, schools, parks and other public requirements; protecting property against blight and depreciation; encouraging the most appropriate use of land, buildings and other structures throughout the County; securing economy in government expenditures; and for other purposes, all in accordance with a comprehensive plan for the development of the County. Section 200-20. Authority. This Title 2 is enacted pursuant to Gwinnett County’s authority to adopt plans and exercise the power of zoning granted by the Constitution of the State of Georgia, Article 9, Section 2; pursuant to Chapters 66 and 70 of Title 36 of the Official Code of Georgia Annotated; by the Georgia Planning Act of 1989; by Gwinnett County’s authority to enact regulations and exercise powers granted by local laws and by the County’s general police powers; and by other powers and authority provided by applicable federal, state, and local laws. Section 200-30. Incorporation of Official Zoning Map. 200-30.1 The location and boundaries of the Zoning Districts are hereby established as shown on the set of maps entitled "Official Gwinnett County Zoning Map" which are hereby made a part of this UDO. -

Vacant Land/Lot Seller Advisory When in Doubt - Disclose!

RE/MAX Sedona Vacant Land/Lot Seller Advisory When in doubt - disclose! Sellers are obligated by law to disclose all known material 2) Access: Both legal and physical access is addressed. (important) facts about the property to the buyer. Arizona law requires that you disclose material facts about the property 3) Use: This section asks for information regarding the current whether or not you are asked by the buyer or a real estate agent, and past use of the property. or when asked to complete a disclosure form. There are also some very specific seller disclosures that you are required by 4) Utilities: You are asked whether the property currently statute to make. Additionally, you may be required to receives the listed utilities, and if so, to identify the provider. complete and record an Affidavit of Disclosure if selling property in an unincorporated area of a county. 5) Water: The water source and any known information about drinking water are addressed. Additionally, the section asks for If the buyer asks you about an aspect of the property, you have a information on any irrigation rights or other water-related duty to disclose the information, regardless of whether or not you issues pertaining to the property. consider the information material. You also have a legal duty to disclose facts when disclosure is necessary to prevent a pre- 6) Sewer/Waste Water Treatment: There are many questions vious statement from being misleading or a misrepresentation: for dealing with the topic of sewer or wastewater treatment as a example, if something changes. However, a seller does not result of claims involving alleged misrepresentations concern- generally have a legal obligation to correct defects in the ing the availability of a sewer connection. -

DOR Code List 02252009

Property Use Description 0000 Vacant Residential - lot & acreage less than 5 acres 0030 Vacant Condo (development land) 0033 Vacant PUD 0040 Vacant Condo Rec Area Dev Own- w/possible XFSB 0041 Condo Rec Area Assn Own - open/green space (939) 0051 Subdivision common area - open/green space, assn owned (938-all Dept except MUCA; 939-MUCA Dept use 0060 Mobile Home, Vacant - individual lot owners in a platted subdivision 0061 Mobile Home Park Subdivision, Vacant 0063 Mobile Home Condo, vacant, assn owned - common area, etc. (938) 0090 Vacant Residential Land w/XFSB 0110 Single Family Home 0133 Planned Unit Development 0260 Mobile Home, with improvement - individual lot owners in a subdivision 0261 Mobile Home Subdivision, Co-op, individual owned - unrecorded M/H parks, improved 0262 Mobile Home Condo, individual/assn owned, improved or vacant 0310 Apartments (50 units or more) 0311 Apartments (10 units to 49 units) 0430 Condominium 0431 Condominium (lease only) 0435 Condo Parking Space 0436 Condo Conversion - apartments/Platted Condo with apartment use 0442 Interval Ownership 0443 Time Share 0550 CO-OP Apartments 0752 Miscellaneous Residential - boarding house, etc. ALF less than 10 units 0810 Single Family - more than one house per parcel 0820 Duplex-Triplex-Fourplex 0821 Townhouse, multi-story units with separate entrances 0822 Apartment House-Boarding House (5-9 units) 1000 Vacant Commercial Land - lot & acreage 1051 Vacant Commercial Common Element 1090 Vacant Commercial Land w/XFSB 1120 Single Building Store - free standing (not otherwise -

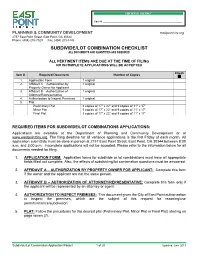

Subdivide/Lot Combination Checklist All Documents and Quantities Are Required

FOR OFFICE USE ONLY Case #: ______________________________________________________________ PLANNING & COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT eastpointcity.org 2757 East Point Street, East Point, GA 30344 Phone: (404) 270-7029 Fax: (404) 209-5148 SUBDIVIDE/LOT COMBINATION CHECKLIST ALL DOCUMENTS AND QUANTITIES ARE REQUIRED ALL PERTINENT ITEMS ARE DUE AT THE TIME OF FILING NO INCOMPLETE APPLICATIONS WILL BE ACCEPTED Check Item # Required Document Number of Copies 1. Application Form 1 original 2. Affidavit A – Authorization by 1 original Property Owner for Applicant 3. Affidavit B – Authorization of 1 original Attorney/Representative 4. Authorization to Inspect Premises 1 original 5. Plat Preliminary Plat 3 copies of 17” x 22” and 9 copies of 11” x 17” Minor Plat 3 copies of 17” x 22” and 9 copies of 11” x 17” Final Plat 3 copies of 17” x 22” and 9 copies of 11” x 17” REQUIRED ITEMS FOR SUBDIVIDE/LOT COMBINATIONS APPLICATIONS: Applications are available at the Department of Planning and Community Development or at www.eastpointcity.org. The filing deadline for all variance applications is the first Friday of each month. All application submittals must be done in person at 2757 East Point Street, East Point, GA 30344 between 8:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. Incomplete applications will not be accepted. Please refer to the information below for all documents needed for filing. A PRE-APPLICATION APPOINTMENT IS REQUIRED PRIOR TO FILING. 1. APPLICATION FORM: Application forms for subdivide or lot combinations must have all appropriate fields filled out complete. Also, the effects of subdividing/lot combination questions must be answered. 2. -

Zoning Bylaws of the Town of Granville

ZONING BYLAWS OF THE TOWN OF GRANVILLE Index Section Title Page Section 1.0 Purpose and Definitions ....................................................... 2 1.1 Purpose ................................................................................... 2 1.2 Definitions.............................................................................. 2 Section 2.0 Establishment of Zoning Districts ....................................... 8 2.1 Types of Districts ................................................................... 8 2.1.2 Floodplain Overlay District ................................................... 8 Section 3.0 Use Regulations ..................................................................... 8 3.1 Agricultural-Residential District ............................................ 8 3.2 Permitted Uses ....................................................................... 8 3.3 Uses Permitted on Special Authorization .............................. 8 3.4 Accessory Uses in Agricultural-Residential District ............. 9 3.5 Nonconforming Uses ........................................................... 10 3.6 Alterations ............................................................................ 10 3.7 Accessory Buildings ............................................................ 10 3.8 Area, Yard, and Coverage Regulations................................ 11 3.9 Back Land Lots .................................................................... 11 3.10 Table of Dimensions ...........................................................