Saariaho X Koh Saariaho X Koh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNOUNCING the 2013-2014 SEASON of the OSM the Orchestre Symphonique De Montréal Celebrates Its 80Th Season

ANNOUNCING THE 2013-2014 SEASON OF THE OSM The Orchestre symphonique de Montréal celebrates its 80th season Great works conducted by Kent Nagano: Opening the season: Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust and Symphony fantastique Mahler’s Symphony No. 7, Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3, Beethoven’s Symphonies Nos. 2 and 4, Bach’s Mass in B Minor, Brahms’s Symphony No. 3 Concluding the season: three concerts, including Saint-Saëns’s Symphony No. 3, and an open-door day to inaugurate the Grand Orgue Pierre Béique Premiere of eight new works: Arcuri, Bertrand, Gilbert, Good, Hatzis, Hefti, Ryan, Saariaho Groundbreaking programs: OSM artist in residence: James Ehnes Introduction of the series OSM Express OSM Éclaté: focusing on Beethoven and Frank Zappa Second edition of Fréquence OSM Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition in collaboration with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts Two programs with the OSM Chamber Choir conducted by Andrew Megill Prestigious guest conductors and soloists, including conductors Jean-Claude Casadesus, James Conlon, Sir Andrew Davis and Michel Plasson, pianists Yuja Wang, Radu Lupu, Stephen Hough, Marc-André Hamelin and Jan Lisiecki cellists Truls Mørk, Gautier Capuçon and Jian Wang violinists Gidon Kremer and Midori, violist Pinchas Zukerman soprano Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo-soprano Ann Hallenberg, tenor Michael Schade and bass-baritone Philippe Sly A new Christmas story recounted by Fred Pellerin Music & Imagery: Beethoven’s Fifth OSM Pops: Hats off to Les Belles-sœurs and La Symphonie rapaillée Symphonic Duo: Adam Cohen -

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

É M I L I E Livret D’Amin Maalouf

KAIJA SAARIAHO É M I L I E Livret d’Amin Maalouf Opéra en neuf scènes 2010 OPERA de LYON LIVRET 5 Fiche technique 7 L’argument 10 Le(s) personnage(s) 16 ÉMILIE CAHIER de LECTURES Voltaire 37 Épitaphe pour Émilie du Châtelet Kaija Saariaho 38 Émilie pour Karita Émilie du Châtelet 43 Les grandes machines du bonheur Serge Lamothe 48 Feu, lumière, couleurs, les intuitions d’Émilie 51 Les derniers mois de la dame des Lumières Émilie du Châtelet 59 Mon malheureux secret 60 Je suis bien indignée de vous aimer autant 61 Voltaire Correspondance CARNET de NOTES Kaija Saariaho 66 Repères biographiques 69 Discographie, Vidéographie, Internet Madame du Châtelet 72 Notice bibliographique Amin Maalouf 73 Repères biographiques 74 Notice bibliographique Illustration. Planches de l’Encyclopédie de Diderot et D’Alembert, Paris, 1751-1772 Gravures du Recueil de planches sur les sciences, les arts libéraux & les arts méchaniques, volumes V & XII LIVRET Le livret est écrit par l’écrivain et romancier Amin Maalouf. Il s’inspire de la vie et des travaux d’Émilie du Châtelet. Émilie est le quatrième livret composé par Amin Maalouf pour et avec Kaija Saariaho, après L’Amour de loin, Adriana Mater 5 et La Passion de Simone. PARTITION Kaija Saariaho commence l’écriture de la partition orches- trale en septembre 2008 et la termine le 19 mai 2009. L’œuvre a été composée à Paris et à Courtempierre (Loiret). Émilie est une commande de l’Opéra national de Lyon, du Barbican Centre de Londres et de la Fondation Gulbenkian. Elle est publiée par Chester Music Ltd. -

Kaija Saariaho

Kaija Saariaho TRIOSDANN • FREUND • HAKKILA • HELASVUO JODELET • KARTTUNEN • KOVACIC 1 KAIJA SAARIAHO (1952) 1 Mirage (2007; chamber version) for soprano, cello and piano 15’17 Pia Freund, Anssi Karttunen, Tuija Hakkila Cloud Trio (2009) for violin, viola and cello 16’12 2 I. Calmo, meditato 3’01 3 II. Sempre dolce, ma energico, sempre a tempo 3’46 4 III. Sempre energico 2’34 5 IV. Tranquillo ma sempre molto espressivo 6’50 Zebra Trio: Ernst Kovacic, Steven Dann, Anssi Karttunen 6 Cendres (1998) for alto flute, cello and piano 9’57 Mika Helasvuo, Anssi Karttunen, Tuija Hakkila Je sens un deuxième coeur (2003) for viola, cello and piano 19’07 7 I. Je dévoile ma peau 4’21 8 II. Ouvre-moi, vite! 2’16 9 III. Dans le rêve, elle l’attendait 4’10 10 IV. Il faut que j’entre 2’34 11 V. Je sens un deuxième coeur qui bat tout près du mien 5’45 Steven Dann, Anssi Karttunen, Tuija Hakkila 2 Serenatas (2008) for percussion, cello and piano 16’03 12 Delicato 2’49 13 Agitato 3’13 14 Dolce 1’22 15 Languido 5’41 16 Misterioso 2’56 Florent Jodelet, Anssi Karttunen, Tuija Hakkila STEVEN DANN, viola PIA FREUND, soprano TUIJA HAKKILA, piano MIKAEL HELASVUO, alto flute FLORENT JODELET, percussion ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cello ERNST KOVACIC, violin 3 n the programme note for her string trio piece Cloud Trio, Kaija Saariaho (b. 1952) discusses how Ishe came about the title of the work, recalling her impressions of the French Alps and the cloud formations drifting over the mountains. -

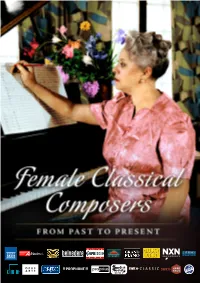

Female Composer Segment Catalogue

FEMALE CLASSICAL COMPOSERS from past to present ʻFreed from the shackles and tatters of the old tradition and prejudice, American and European women in music are now universally hailed as important factors in the concert and teaching fields and as … fast developing assets in the creative spheres of the profession.’ This affirmation was made in 1935 by Frédérique Petrides, the Belgian-born female violinist, conductor, teacher and publisher who was a pioneering advocate for women in music. Some 80 years on, it’s gratifying to note how her words have been rewarded with substance in this catalogue of music by women composers. Petrides was able to look back on the foundations laid by those who were well-connected by family name, such as Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, and survey the crop of composers active in her own time, including Louise Talma and Amy Beach in America, Rebecca Clarke and Liza Lehmann in England, Nadia Boulanger in France and Lou Koster in Luxembourg. She could hardly have foreseen, however, the creative explosion in the latter half of the 20th century generated by a whole new raft of female composers – a happy development that continues today. We hope you will enjoy exploring this catalogue that has not only historical depth but a truly international voice, as exemplified in the works of the significant number of 21st-century composers: be it the highly colourful and accessible American chamber music of Jennifer Higdon, the Asian hues of Vivian Fung’s imaginative scores, the ancient-and-modern syntheses of Sofia Gubaidulina, or the hallmark symphonic sounds of the Russian-born Alla Pavlova. -

Professor Bad Trip Uproar Wales New Music Ensemble

PROFESSOR BAD TRIP UPROAR WALES NEW MUSIC ENSEMBLE UPROAR.org.uk @UPROAR_Wales “…virtuosic, exuberant and playful” **** On UPROAR’s 10x10, The Guardian 2018. UPROAR Funders 2019-2020 We would like to thank our funders and supporters who made this programme possible: Arts Council of Wales Diaphonique Foyle Foundation Garfi eld Weston Foundation Hinrichsen Foundation Italian Cultural Institute Oakdale Trust PRS Foundation The Stafford House Foundation Tŷ Cerdd RVW Trust Wales Arts International Donations Private donation in memory of Peter Reynolds Peter Golob Pyrenees Cycle Ride Fund Sally Groves Professor Mick Peake UPROAR gratefully acknowledges the kind support of Electroacoustic Wales, Tessa Shellens, Michael Ellison, Andrew Rafferty Charity Registration Number: 1174587 The Oakdale Trust ABOUT UPROAR UPROAR is the new contemporary music ensemble for Wales. Led by conductor Michael Rafferty, the ensemble comprises some of the UK’s most accomplished musicians specialising in new music. Committed and hungry to bring the most raw, adventurous and imaginative new music from Welsh and international composers to audiences in Wales and the UK. Professor Bad Trip is the second project from UPROAR which launched in 2018 with its inaugural sell-out performance in Cardiff and gained critical acclaim in local and national press. UPROAR Artistic Director & Conductor Michael Rafferty Michael Rafferty, founder of UPROAR, is an award winning conductor based in South Wales. Passionate about contemporary culture, he conducts the world’s fi nest contemporary music ensembles and has collaborated with over 100 living composers. He co-founded Music Theatre Wales and was its Music Director for 25 years. He was awarded an MBE in 2016 for services to music in Wales. -

October 21 and 24, 2015

XcapeSeason_SongscapeProgram.pdf 1 9/30/15 2:41 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Message from the Artistic Director Welcome to the 2015-16 Season of the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players! And, welcome to our first concert, Songscape, in which we’ll examine the nature of utterance and memory through song. The beginning of every concert season is a fresh opportunity for exploration: new ideas to be illuminated and new options to be considered. But with Songscape we’ll start by thinking about the end of things, by examining the language of loss. In Death Speaks, David Lang culls photo by Bill Dean through the songs of Franz Schubert for instances in which death speaks to the living. Lang uses excerpts from thirty-two songs, cutting and assembling them to form a melancholy collage of music and a terrifying image of the voice of death. Whether as “Der Erlkönig,” in which death is as fleet as a racing horse or Die Schöne Müllerin, in which it is a seductress, beckoning the miller to cross the veil, the voice of death is rendered audible, personal and powerful. Lee Hyla’s We Speak Etruscan imagines the sound of ancient Etruscan as it might be spoken by modern reed instruments. It also forces us to contend with the death of a language. How did Etruscan (from this word we get the modern name, Tuscany), the forerunner of Latin, and the language of a major indigenous culture of significant artistic refinement, simply vanish? That is not far from a more tantalizing question: what happens to the past when we can no longer hear its sounds? By this I don’t mean when we can no longer hear the music of the past. -

4 Issue: 2 December 2020 Masthead

Trabzon University e-ISSN: 2618-5652 State Conservatory Vol: 4 Issue: 2 December 2020 Masthead Musicologist: International Journal of Music Studies Volume 4 Issue 2 December 2020 Musicologist is a biannually, peer-reviewed, open access, online periodical published in English by Trabzon University State Conservatory, in Trabzon, Turkey. e-ISSN: 2618-5652 Owner on behalf of Trabzon University State Conservatory Merve Eken KÜÇÜKAKSOY (Director) Editor-In-Chief Abdullah AKAT (İstanbul University – Turkey) Deputy Editor Merve Eken KÜÇÜKAKSOY (Trabzon University – Turkey) Technical Editor Emrah ERGENE (Trabzon University – Turkey) Language Editor Marina KAGANOVA (Colombia University – USA) Editorial Assistant Uğur ASLAN (Trabzon University – Turkey) Contacts Address: Trabzon Üniversitesi Devlet Konservatuvarı Müdürlüğü, Fatih Kampüsü, Söğütlü 61335 Akçaabat/Trabzon, Turkey Web: www.musicologistjournal.com Email: [email protected] All rights reserved. The authors are responsible for all visual elements, including tables, figures, graphics and pictures. They are also responsible for any scholarly citations. Trabzon University does not assume any legal responsibility for the use of any of these materials. ©2017-2020 Trabzon University State Conservatory Editorial Board Alper Maral Ankara Music and Fine Arts University – Turkey Caroline Bithell The University of Manchester – UK Ekaterine Diasamidze Tbilisi State University – Georgia Elif Damla Yavuz Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University – Turkey Erol Köymen The University of Chicago – USA -

New Music Festival November 5-9, 2018

University of Louisville School of Music Presents the Annual New Music Festival November 5-9, 2018 FEATURED GUEST COMPOSER Amy Williams GUEST ARTISTS Sam Pluta Elysian Trombone Consort A/Tonal Ensemble New Music Festival November 5-9, 2018 Amy Williams featured composer Table of Contents Greetings From Dr. Christopher Doane, Dean of the School of Music 3 Biography Amy Williams, Featured Composer 5 Sunday, November 4 Morton Feldman: His Life & Works Program 6 Monday, November 5 Faculty Chamber Music Program 10 Tuesday, November 6 Electronic Music Program 18 Wednesday, November 7 University Symphony Orchestra Program 22 Personnel 25 Thursday, November 8 Collegiate Chorale & Cardinal Singers Program 26 Personnel 32 Friday, November 9 New Music Ensemble & Wind Ensemble Program 34 Personnel 40 Guest Artist Biographies 41 Composer Biographies 43 1 Media partnership provided by Louisville Public Media 502-852-6907 louisville.edu/music facebook.com/uoflmusic Additional 2018 New Music Festival Events: Monday, November 5, 2018 Music Building Room LL28 Computer Music Composition Seminar with Sam Pluta Wednesday, November 7, 2018 Music Building Room 125 Composition Seminar with Amy Williams Thursday, November 8, 2018 Bird Recital Hall Convocation Lecture with Amy Williams To access the New Music Festival program: For Apple users, please scan the accompanying QR code. For Android users, please visit www.qrstuff.com/scan and allow the website to access your device’s camera. The New Music Festival Organizing Committee Dr. John Ritz, chair Dr. Kent Hatteberg Professor Kimcherie Lloyd Dr. Frederick Speck Dr. Krzysztof Wołek 2 The School of Music at the University of Louisville is strongly identified with the performance of contemporary music and the creation of new music. -

Walt Disney Concert Hall Opening Season

WALT DISNEY CONCERT HALL 2014/15 CHRONOLOGICAL LISTING OF EVENTS SEPTEMBER 2014 LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Thursday, September 25, 2014, at 7 PM YOLA AT LACHSA CHOIR AND MUSICIANS Daniel Cohen, conductor Neighborhood Concert Martin Chalifour, violin Luckman Auditorium PUENTE Oye como va VIVALDI/PIAZZOLLA Selections from The Four Seasons MILHAUD Le boeuf sur le toit LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Tuesday, September 30, 2014, at 7 PM -OPENING NIGHT GALA- Walt Disney Concert Hall Gustavo Dudamel (Non-subscription) Itzhak Perlman, violin Dan Higgins, alto saxophone Glenn Paulson, vibraphone Mike Valerio, string bass U.S. Army Herald Trumpets Los Angeles Children’s Chorus Anne Tomlinson, artistic director Netia Jones, projection design Robin Gray, lighting design A John Williams Celebration Olympic Fanfare and Theme Soundings Three Pieces from Schindler’s List Cadenza and Variations from Fiddler on the Roof* The Duel from The Adventures of Tintin Escapades from Catch Me if You Can Throne Room and Finale from Star Wars *Includes excerpts from the original Jerry Bock score from Fiddler on the Roof. OCTOBER 2014 LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Thursday, October 2, 2014, at 8 PM Walt Disney Concert Hall Friday, October 3, 2014, at 11 AM Saturday, October 4, 2014, at 8 PM Sunday, October 5, 2014, at 2 PM Gustavo Dudamel, conductor Sō Percussion LANG Man Made (U.S. premiere, LA Phil co-commission) MAHLER Symphony No. 5 GREEN UMBRELLA Tuesday, October 7, 2014, at 8 PM Walt Disney Concert Hall Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group Sō Percussion Joseph Pereira, -

New Approaches to Performance and the Practical

New Approaches to Performance and the Practical Application of Techniques from Non-Western and Electro-acoustic Musics in Compositions for Solo Cello since 1950: A Personal Approach and Two Case Studies Rebecca Turner Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of PhD in Music (Performance Practice) Department of Music Goldsmiths College, University of London 2014 Supervisor Professor Alexander Ivashkin Declaration I, Rebecca Turner, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work submitted in this thesis is my own and where the contributions of others are made they are clearly acknowledged. Signed……………………………………………… Date…………………….. Rebecca Turner ii For Alexander Ivashkin, 1948-2014 iii Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the wisdom, encouragement, and guidance from my academic supervisor, the late Professor Alexander Ivashkin; it was an honour and a privilege to be his student. I am also eternally grateful for the tutelage of my performance supervisor, Natalia Pavlutskaya, for her support and encouragement over the years; she has taught me to always strive for excellence in all areas of my life. I am enormously grateful to Franghiz Ali-Zadeh and Michael Cryne for allowing me to feature their compositions in my case studies, and also for generosity giving up their time for our interviews. I am indebted to the staff of the Music Department at Goldsmiths College, London University, both for supporting me in my research and also being so generous with the use of the available facilities; in particular the Stanley Glasser Electronic Music Studios. I also thank C.f. Peters Corp., Breitkopf & Härtel, Schott Music Ltd, MUSIKVERLA HANS SIKORSKI GMBH & CO, for their kind permission to quote from copyrighted material. -

Reinterpreting the Concerto Three Finnish Clarinet Concertos Written For

Reinterpreting the Concerto Three Finnish clarinet concertos written for Kari Kriikku Sapphire Clare Littler MA by Research University of York Music December 2018 Reinterpreting the Concerto: Three Finnish clarinet concertos written for Kari Kriikku Abstract The origins of the word concerto can be traced to two different sources: the first is the Italian translation, to mean ‘agreement’, and the other stems from the Latin concertare, which means ‘to compete’. Ironically, the duality presented by these two translations encapsulates the true meaning of the concerto: opposition and resolution. This thesis focuses on Finnish works for clarinet and orchestra composed for Kari Kriikku in the last forty years, and seeks to analyse three in depth: Jukka Tiensuu’s Puro (1989); Magnus Lindberg’s Clarinet Concerto (2002); and Kaija Saariaho’s D’OM LE VRAI SENS (2010). The works have been chosen as these composers were all born around a similar time in Finland, and all worked with the same clarinettist, whom they all know personally. Through analysis, Reinterpreting the Concerto seeks to discover how each of these composers tackled the pre- existing model of the concerto, and suggest reasons for compositional decisions. The thesis will end with a discussion of clarinet technique, and how much writing for Kriikku in particular may have influenced the works. This essay will be formed of several sections, with the first examining the traits which could be considered important to each of the pieces: form, and how this results in the linear progression of the work; continuity and discontinuity created through melodic treatment, and how the soloist interacts with the ensemble.