Arxiv:2101.00013V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 3 Aug 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aquarius Aries Pisces Taurus

Zodiac Constellation Cards Aquarius Pisces January 21 – February 20 – February 19 March 20 Aries Taurus March 21 – April 21 – April 20 May 21 Zodiac Constellation Cards Gemini Cancer May 22 – June 22 – June 21 July 22 Leo Virgo July 23 – August 23 – August 22 September 23 Zodiac Constellation Cards Libra Scorpio September 24 – October 23 – October 22 November 22 Sagittarius Capricorn November 23 – December 23 – December 22 January 20 Zodiac Constellations There are 12 zodiac constellations that form a belt around the earth. This belt is considered special because it is where the sun, the moon, and the planets all move. The word zodiac means “circle of figures” or “circle of life”. As the earth revolves around the sun, different parts of the sky become visible. Each month, one of the 12 constellations show up above the horizon in the east and disappears below the horizon in the west. If you are born under a particular sign, the constellation it is named for can’t be seen at night. Instead, the sun is passing through it around that time of year making it a daytime constellation that you can’t see! Aquarius Aries Cancer Capricorn Gemini Leo January 21 – March 21 – June 22 – December 23 – May 22 – July 23 – February 19 April 20 July 22 January 20 June 21 August 22 Libra Pisces Sagittarius Scorpio Taurus Virgo September 24 – February 20 – November 23 – October 23 – April 21 – August 23 – October 22 March 20 December 22 November 22 May 21 September 23 1. Why is the belt that the constellations form around the earth special? 2. -

Where Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps

W here Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps Abo ut the Activity Whe re are the distant worlds in the night sky? Use a star map to find constellations and to identify stars with extrasolar planets. (Northern Hemisphere only, naked eye) Topics Covered • How to find Constellations • Where we have found planets around other stars Participants Adults, teens, families with children 8 years and up If a school/youth group, 10 years and older 1 to 4 participants per map Materials Needed Location and Timing • Current month's Star Map for the Use this activity at a star party on a public (included) dark, clear night. Timing depends only • At least one set Planetary on how long you want to observe. Postcards with Key (included) • A small (red) flashlight • (Optional) Print list of Visible Stars with Planets (included) Included in This Packet Page Detailed Activity Description 2 Helpful Hints 4 Background Information 5 Planetary Postcards 7 Key Planetary Postcards 9 Star Maps 20 Visible Stars With Planets 33 © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Detailed Activity Description Leader’s Role Participants’ Roles (Anticipated) Introduction: To Ask: Who has heard that scientists have found planets around stars other than our own Sun? How many of these stars might you think have been found? Anyone ever see a star that has planets around it? (our own Sun, some may know of other stars) We can’t see the planets around other stars, but we can see the star. -

Lecture 7: the Local Group and Nearby Clusters

Lecture 7: the Local Group and nearby clusters • in this lecture we move up in scale, to explore typical clusters of galaxies – the Local Group is an example of a not very rich cluster • interesting topics include: – clusters and the structure of the Universe – the fate of galaxies: stable, destroyed or cannibals? Galaxies – AS 3011 1 the Local Group Galaxies – AS 3011 2 1 Inner Solar System Galaxies – AS 3011 3 Galaxies – AS 3011 4 2 some Local Group galaxies, roughly to the same physical scale: M31, Leo I LMC, M32 SMC MW M33 (images courtesy AAO) Galaxies – AS 3011 5 first impressions • there are some obvious properties of the Local Group: – it’s mostly empty, i.e. galaxies are quite distant from each other – with some exceptions like satellite galaxies – the three spirals are easily the biggest – dwarf galaxies are on the outskirts of the group • how typical is this of other galaxy groups? – turns out that the Local group is not very rich in galaxies Galaxies – AS 3011 6 3 groups and clusters • groups contain a smaller number of galaxies than clusters, and are more compact in both space and velocity spread: group: cluster: no. galaxies ~10+ >50 core radius ~300 kpc ~300 kpc median radius ~1 Mpc ~ 3Mpc v-dispersion 150 km/s 800 km/s M/L ~200 ~200 13 15 total mass few 10 Msolar few 10 Msolar Galaxies – AS 3011 7 classifying the Local Group • the Local Group has only about 10 significant galaxies 8 (L > 10 Lsolar), so does not qualify as a cluster – NB, dwarf spheroidals etc. -

Newpointe-Catalog

NewPointe® Constellation Collections More value from Batesville Constellation Collections 18 Gauge Steel Caskets Leo Collection Leo Brushed Black Silver velvet interior Leo Brushed Black shown with Praying Hands decorative kit. 257178 - half couch Choose from 11 designs. 262411 - full couch See page 15 for your options. • Includes decorative kit option for lid Leo Painted Silver Silver velvet interior 257172 - half couch 262415 - full couch • Includes decorative kit option for lid Leo Brushed Ruby Leo Brushed Blue Leo Painted Sand Leo Painted White Moss Pink velvet interior Light Blue velvet interior Champagne velvet interior Moss Pink velvet interior 257177 - half couch 257179 - half couch 257173 - half couch 257166 - half couch 262410 - full couch 262412 - full couch 262416 - full couch 262414 - full couch • Includes decorative kit option • Includes decorative kit option • Includes decorative kit option • Includes decorative kit option for lid for lid for lid for lid 2 All caskets not available in all locations. Please check to ensure availability in your area. 18 Gauge Steel Caskets Virgo Collection Virgo White/Pink Moss Pink crepe interior| $845 250673 - half couch Virgo White/Pink shown with Roses 254258 - full couch decorative kit and corner decals. Choose from 11 designs. • Includes decorative kit option See page 15 for your options. for lid and corner decals Virgo Blue Light Blue crepe interior 250658 - half couch 254255 - full couch • Includes decorative kit option for lid and corner decals Virgo Silver Virgo White Virgo Copper -

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

The Detailed Properties of Leo V, Pisces II and Canes Venatici II

Haverford College Haverford Scholarship Faculty Publications Astronomy 2012 Tidal Signatures in the Faintest Milky Way Satellites: The Detailed Properties of Leo V, Pisces II and Canes Venatici II David J. Sand Jay Strader Beth Willman Haverford College Dennis Zaritsky Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.haverford.edu/astronomy_facpubs Repository Citation Sand, David J., Jay Strader, Beth Willman, Dennis Zaritsky, Brian Mcleod, Nelson Caldwell, Anil Seth, and Edward Olszewski. "Tidal Signatures In The Faintest Milky Way Satellites: The Detailed Properties Of Leo V, Pisces Ii, And Canes Venatici Ii." The Astrophysical Journal 756.1 (2012): 79. Print. This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Astronomy at Haverford Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Haverford Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Astrophysical Journal, 756:79 (14pp), 2012 September 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/756/1/79 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. TIDAL SIGNATURES IN THE FAINTEST MILKY WAY SATELLITES: THE DETAILED PROPERTIES OF LEO V, PISCES II, AND CANES VENATICI II∗ David J. Sand1,2,7, Jay Strader3, Beth Willman4, Dennis Zaritsky5, Brian McLeod3, Nelson Caldwell3, Anil Seth6, and Edward Olszewski5 1 Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network, 6740 Cortona Drive, Suite 102, Santa Barbara, CA 93117, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Physics, Broida Hall, -

H I Deficiency in Groups : What Can We Learn from Eridanus ?

Bull. Astr. Soc. India (2004) 32, 239{245 H i de¯ciency in groups : what can we learn from Eridanus ? A. Omar¤y Raman Research Institute, Sadashivanagar, Bangalore 560 080, India Received 14 July 2004; accepted 24 August 2004 Abstract. The H i content of the Eridanus group of galaxies is studied using the GMRT observations and the HIPASS data. A signi¯cant H i de¯ciency up to a factor of 2 ¡ 3 is observed in galaxies in the Eridanus group. The de¯ciency is found to be directly correlated with the projected galaxy density and inversely correlated with the line-of-sight radial velocity. It is suggested that the H i de¯ciency is due to tidal interactions. An important implication is that signi¯cant evolution of galaxies can take place in a group environment. Keywords : galaxies: ISM { galaxies: interactions { galaxies: kinematics and dynamics { galaxies: evolution { galaxies: clusters: individual: Eridanus group { radio lines: galaxies 1. Introduction Spiral galaxies in the cores of clusters are known to be H i de¯cient compared to their ¯eld counterparts (Davies and Lewis 1973, Giovanelli and Haynes 1985, Cayatte et al. 1990, Bravo-Alfaro et al. 2000). Several gas-removal mechanisms have been proposed to explain the H i de¯ciency in cluster galaxies. There are convincing results from both the simulations and the observations that ram-pressure stripping can be active in galaxies which have crossed the high ICM (Intra Cluster Medium) density region in the cores of clusters (Vollmer et al. 2001, van Gorkom 2003). However, it is not clear that all H i de¯cient galaxies have crossed the core. -

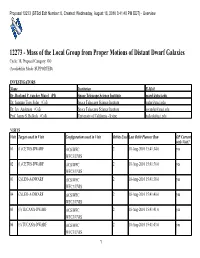

12273 (Stsci Edit Number: 0, Created: Wednesday, August 18, 2010 3:41:48 PM EDT) - Overview

Proposal 12273 (STScI Edit Number: 0, Created: Wednesday, August 18, 2010 3:41:48 PM EDT) - Overview 12273 - Mass of the Local Group from Proper Motions of Distant Dwarf Galaxies Cycle: 18, Proposal Category: GO (Availability Mode: SUPPORTED) INVESTIGATORS Name Institution E-Mail Dr. Roeland P. van der Marel (PI) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Dr. Sangmo Tony Sohn (CoI) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Dr. Jay Anderson (CoI) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Prof. James S. Bullock (CoI) University of California - Irvine [email protected] VISITS Visit Targets used in Visit Configurations used in Visit Orbits Used Last Orbit Planner Run OP Current with Visit? 01 (1) CETUS-DWARF ACS/WFC 2 18-Aug-2010 15:41:34.0 yes WFC3/UVIS 02 (1) CETUS-DWARF ACS/WFC 2 18-Aug-2010 15:41:36.0 yes WFC3/UVIS 03 (2) LEO-A-DWARF ACS/WFC 2 18-Aug-2010 15:41:38.0 yes WFC3/UVIS 04 (2) LEO-A-DWARF ACS/WFC 2 18-Aug-2010 15:41:40.0 yes WFC3/UVIS 05 (3) TUCANA-DWARF ACS/WFC 2 18-Aug-2010 15:41:41.0 yes WFC3/UVIS 06 (3) TUCANA-DWARF ACS/WFC 2 18-Aug-2010 15:41:43.0 yes WFC3/UVIS 1 Proposal 12273 (STScI Edit Number: 0, Created: Wednesday, August 18, 2010 3:41:48 PM EDT) - Overview Visit Targets used in Visit Configurations used in Visit Orbits Used Last Orbit Planner Run OP Current with Visit? 07 (4) SAGITTARIUS-DWARF- ACS/WFC 2 18-Aug-2010 15:41:44.0 yes IRREGULAR WFC3/UVIS 08 (4) SAGITTARIUS-DWARF- ACS/WFC 2 18-Aug-2010 15:41:46.0 yes IRREGULAR WFC3/UVIS 09 (4) SAGITTARIUS-DWARF- ACS/WFC 2 18-Aug-2010 15:41:47.0 yes IRREGULAR WFC3/UVIS 18 Total Orbits Used ABSTRACT The Local Group and its two dominant spirals, the Milky Way and M31, have become the benchmark for testing many aspects of cosmological and galaxy formation theories, due to many exciting new discoveries in the past decade. -

V. Spatially-Resolved Stellar Angular Momentum, Velocity Dispersion, and Higher Moments of the 41 Most Massive Local Early-Type Galaxies

MNRAS 000,1{20 (2016) Preprint 9 September 2016 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 The MASSIVE Survey - V. Spatially-Resolved Stellar Angular Momentum, Velocity Dispersion, and Higher Moments of the 41 Most Massive Local Early-Type Galaxies Melanie Veale,1;2 Chung-Pei Ma,1 Jens Thomas,3 Jenny E. Greene,4 Nicholas J. McConnell,5 Jonelle Walsh,6 Jennifer Ito,1 John P. Blakeslee,5 Ryan Janish2 1Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 2Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 3Max Plank-Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Giessenbachstr. 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany 4Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA 5Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, NRC Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, Victoria BC V9E2E7, Canada 6George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT We present spatially-resolved two-dimensional stellar kinematics for the 41 most mas- ∗ 11:8 sive early-type galaxies (MK . −25:7 mag, stellar mass M & 10 M ) of the volume-limited (D < 108 Mpc) MASSIVE survey. For each galaxy, we obtain high- quality spectra in the wavelength range of 3650 to 5850 A˚ from the 246-fiber Mitchell integral-field spectrograph (IFS) at McDonald Observatory, covering a 10700 × 10700 field of view (often reaching 2 to 3 effective radii). We measure the 2-D spatial distri- bution of each galaxy's angular momentum (λ and fast or slow rotator status), velocity dispersion (σ), and higher-order non-Gaussian velocity features (Gauss-Hermite mo- ments h3 to h6). -

1410.0681V1.Pdf

ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION IN THE ASTROPHYSICAL JOURNAL Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 05/12/14 THE QUENCHING OF THE ULTRA-FAINT DWARF GALAXIES IN THE REIONIZATION ERA1 THOMAS M. BROWN2, JASON TUMLINSON2, MARLA GEHA3, JOSHUA D. SIMON4,LUIS C. VARGAS3,DON A. VANDENBERG5,EVAN N. KIRBY6, JASON S. KALIRAI2,7,ROBERTO J. AVILA2, MARIO GENNARO2,HENRY C. FERGUSON2 RICARDO R. MUÑOZ8,PURAGRA GUHATHAKURTA9, AND ALVIO RENZINI10 Accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal ABSTRACT We present new constraints on the star formation histories of six ultra-faint dwarf galaxies: Bootes I, Canes Venatici II, Coma Berenices, Hercules, Leo IV, and Ursa Major I. Our analysis employs a combination of high-precision photometry obtained with the Advanced Camera for Surveys on the Hubble Space Telescope, medium-resolutionspectroscopy obtained with the DEep Imaging Multi-Object Spectrograph on the W.M. Keck Observatory, and updated Victoria-Regina isochrones tailored to the abundance patterns appropriate for these galaxies. The data for five of these Milky Way satellites are best fit by a star formation history where at least 75% of the stars formed by z ∼ 10 (13.3 Gyr ago). All of the galaxies are consistent with 80% of the stars forming by z ∼ 6 (12.8 Gyr ago) and 100% of the stars forming by z ∼ 3 (11.6 Gyr ago). The similarly ancient populations of these galaxies support the hypothesis that star formation in the smallest dark matter sub-halos was suppressed by a global outside influence, such as the reionization of the universe. Keywords: Local Group — galaxies: dwarf — galaxies: photometry — galaxies: evolution — galaxies: for- mation — galaxies: stellar content 1. -

Astronomy for Kids - Leo

Astronomy for Kids - Leo The Lion Leo is another companion to Orion in our night sky. You can easily find Leo any Leo Map time that Orion is visible by looking East of the Great Hunter. Although Leo is not as large as Orion, it's distinctive shape makes it very easy to pick out. If you click on the link for the map of Leo on the right, you will notice that the outline of the lion's head and the triangle formed by the stars in the lion's hindquarters are two very distinctive shapes that make this constellation very easy to spot. A map of Leo. Regulus - the Heart of the Lion The largest and brightest star in Leo is Regulus. This large blue star shines brightly as the heart of the lion. Although not a giant star, Regulus is still over five times as large as our Sun. A small telescope will show you that Regulus is part of what is called a "binary system". Binary stars are stars that have one or more companions that orbit around the largest star in the group, much like the planets orbit around our Sun. Find Out More About Leo Chris Dolan's Leo Page Chris Dolan's Leo page has lots of technical information about the stars that make up Leo Richard Dibon-Smith's Leo Page Richard Dibon-Smith's Leo page has a very good explanation of the mythology behind Gemini as well as an excellent reference to its stars and other interesting celestial companions. Original Content Copyright ©2003 Astronomy for Kids Permission is granted for reproduction for non-commercial educational purposes. -

The Feeble Giant. Discovery of a Large and Diffuse Milky Way Dwarf Galaxy in the Constellation of Crater

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo MNRAS 459, 2370–2378 (2016) doi:10.1093/mnras/stw733 Advance Access publication 2016 April 13 The feeble giant. Discovery of a large and diffuse Milky Way dwarf galaxy in the constellation of Crater G. Torrealba,‹ S. E. Koposov, V. Belokurov and M. Irwin Institute of Astronomy, Madingley Rd, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/459/3/2370/2595158 by University of Cambridge user on 24 July 2019 Accepted 2016 March 24. Received 2016 March 24; in original form 2016 January 26 ABSTRACT We announce the discovery of the Crater 2 dwarf galaxy, identified in imaging data of the VLT Survey Telescope ATLAS survey. Given its half-light radius of ∼1100 pc, Crater 2 is the fourth largest satellite of the Milky Way, surpassed only by the Large Magellanic Cloud, Small Magellanic Cloud and the Sgr dwarf. With a total luminosity of MV ≈−8, this galaxy is also one of the lowest surface brightness dwarfs. Falling under the nominal detection boundary of 30 mag arcsec−2, it compares in nebulosity to the recently discovered Tuc 2 and Tuc IV and UMa II. Crater 2 is located ∼120 kpc from the Sun and appears to be aligned in 3D with the enigmatic globular cluster Crater, the pair of ultrafaint dwarfs Leo IV and Leo V and the classical dwarf Leo II. We argue that such arrangement is probably not accidental and, in fact, can be viewed as the evidence for the accretion of the Crater-Leo group.