An Outbreak of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 Infection Linked to Unpasteurized Apple Cider in Oklahoma, 1999 Mamadou O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

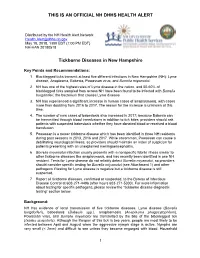

Official Nh Dhhs Health Alert

THIS IS AN OFFICIAL NH DHHS HEALTH ALERT Distributed by the NH Health Alert Network [email protected] May 18, 2018, 1300 EDT (1:00 PM EDT) NH-HAN 20180518 Tickborne Diseases in New Hampshire Key Points and Recommendations: 1. Blacklegged ticks transmit at least five different infections in New Hampshire (NH): Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2. NH has one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the nation, and 50-60% of blacklegged ticks sampled from across NH have been found to be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. 3. NH has experienced a significant increase in human cases of anaplasmosis, with cases more than doubling from 2016 to 2017. The reason for the increase is unknown at this time. 4. The number of new cases of babesiosis also increased in 2017; because Babesia can be transmitted through blood transfusions in addition to tick bites, providers should ask patients with suspected babesiosis whether they have donated blood or received a blood transfusion. 5. Powassan is a newer tickborne disease which has been identified in three NH residents during past seasons in 2013, 2016 and 2017. While uncommon, Powassan can cause a debilitating neurological illness, so providers should maintain an index of suspicion for patients presenting with an unexplained meningoencephalitis. 6. Borrelia miyamotoi infection usually presents with a nonspecific febrile illness similar to other tickborne diseases like anaplasmosis, and has recently been identified in one NH resident. Tests for Lyme disease do not reliably detect Borrelia miyamotoi, so providers should consider specific testing for Borrelia miyamotoi (see Attachment 1) and other pathogens if testing for Lyme disease is negative but a tickborne disease is still suspected. -

E. Coli (STEC) FACT SHEET

Escherichia coli O157:H7 & SHIGA TOXIN PRODUCING E. coli (STEC) FACT SHEET Agent: Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 or other Shiga Toxin Producing E. coli E. coli serotypes producing Shiga toxins. All are • Positive Shiga toxin test (e.g., EIA) gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria that produce Shiga toxin(s). Diagnostic Testing: A. Culture Brief Description: An infection of variable severity 1. Specimen: feces characterized by diarrhea (often bloody) and abdomi- 2. Outfit: Stool culture nal cramps. The illness may be complicated by 3. Lab Form: Form 3416 hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), in which red 4. Lab Test Performed: Bacterial blood cells are destroyed and the kidneys fail. This is isolation and identification. Tests for particularly a problem in children <5 years of age Shiga toxin I and II. PFGE. and the elderly. In the United States, hemolytic 5. Lab: Georgia Public Health Labora- uremic syndrome is the principal cause of acute tory (GPHL) in Decatur, Bacteriol- kidney failure in children, and most cases of ogy hemolytic uremic syndrome are caused by E. coli O157:H7 or another STEC. Another complication is B. Antigen Typing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). As- 1. Specimen: Pure culture ymptomatic infections may also occur. 2. Outfit: Culture referral 3. Laboratory Form 3410 Reservoir: Cattle and possibly deer. Humans may 4. Test performed: Flagella antigen also serve as a reservoir for person-to-person trans- typing mission. 5. Lab: GPHL in Decatur, Bacteriology Mode of Transmission: Ingestion of contaminated Case Classification: food (most often inadequately cooked ground beef) • Suspected: A case of postdiarrheal HUS or but also unpasteurized milk and fruit or vegetables TTP (see HUS case definition in the HUS contaminated with feces. -

Control of Intestinal Protozoa in Dogs and Cats

Control of Intestinal Protozoa 6 in Dogs and Cats ESCCAP Guideline 06 Second Edition – February 2018 1 ESCCAP Malvern Hills Science Park, Geraldine Road, Malvern, Worcestershire, WR14 3SZ, United Kingdom First Edition Published by ESCCAP in August 2011 Second Edition Published in February 2018 © ESCCAP 2018 All rights reserved This publication is made available subject to the condition that any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise is with the prior written permission of ESCCAP. This publication may only be distributed in the covers in which it is first published unless with the prior written permission of ESCCAP. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-907259-53-1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 1: CONSIDERATION OF PET HEALTH AND LIFESTYLE FACTORS 5 2: LIFELONG CONTROL OF MAJOR INTESTINAL PROTOZOA 6 2.1 Giardia duodenalis 6 2.2 Feline Tritrichomonas foetus (syn. T. blagburni) 8 2.3 Cystoisospora (syn. Isospora) spp. 9 2.4 Cryptosporidium spp. 11 2.5 Toxoplasma gondii 12 2.6 Neospora caninum 14 2.7 Hammondia spp. 16 2.8 Sarcocystis spp. 17 3: ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL OF PARASITE TRANSMISSION 18 4: OWNER CONSIDERATIONS IN PREVENTING ZOONOTIC DISEASES 19 5: STAFF, PET OWNER AND COMMUNITY EDUCATION 19 APPENDIX 1 – BACKGROUND 20 APPENDIX 2 – GLOSSARY 21 FIGURES Figure 1: Toxoplasma gondii life cycle 12 Figure 2: Neospora caninum life cycle 14 TABLES Table 1: Characteristics of apicomplexan oocysts found in the faeces of dogs and cats 10 Control of Intestinal Protozoa 6 in Dogs and Cats ESCCAP Guideline 06 Second Edition – February 2018 3 INTRODUCTION A wide range of intestinal protozoa commonly infect dogs and cats throughout Europe; with a few exceptions there seem to be no limitations in geographical distribution. -

Cyclospora Cayetanensis and Cyclosporiasis: an Update

microorganisms Review Cyclospora cayetanensis and Cyclosporiasis: An Update Sonia Almeria 1 , Hediye N. Cinar 1 and Jitender P. Dubey 2,* 1 Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Nutrition (CFSAN), Office of Applied Research and Safety Assessment (OARSA), Division of Virulence Assessment, Laurel, MD 20708, USA 2 Animal Parasitic Disease Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, Building 1001, BARC-East, Beltsville, MD 20705-2350, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 July 2019; Accepted: 2 September 2019; Published: 4 September 2019 Abstract: Cyclospora cayetanensis is a coccidian parasite of humans, with a direct fecal–oral transmission cycle. It is globally distributed and an important cause of foodborne outbreaks of enteric disease in many developed countries, mostly associated with the consumption of contaminated fresh produce. Because oocysts are excreted unsporulated and need to sporulate in the environment, direct person-to-person transmission is unlikely. Infection by C. cayetanensis is remarkably seasonal worldwide, although it varies by geographical regions. Most susceptible populations are children, foreigners, and immunocompromised patients in endemic countries, while in industrialized countries, C. cayetanensis affects people of any age. The risk of infection in developed countries is associated with travel to endemic areas and the domestic consumption of contaminated food, mainly fresh produce imported from endemic regions. Water and soil contaminated with fecal matter may act as a vehicle of transmission for C. cayetanensis infection. The disease is self-limiting in most immunocompetent patients, but it may present as a severe, protracted or chronic diarrhea in some cases, and may colonize extra-intestinal organs in immunocompromised patients. -

The Stem Cell Revolution Revealing Protozoan Parasites' Secrets And

Review The Stem Cell Revolution Revealing Protozoan Parasites’ Secrets and Paving the Way towards Vaccine Development Alena Pance The Wellcome Sanger Institute, Genome Campus, Hinxton Cambridgeshire CB10 1SA, UK; [email protected] Abstract: Protozoan infections are leading causes of morbidity and mortality in humans and some of the most important neglected diseases in the world. Despite relentless efforts devoted to vaccine and drug development, adequate tools to treat and prevent most of these diseases are still lacking. One of the greatest hurdles is the lack of understanding of host–parasite interactions. This gap in our knowledge comes from the fact that these parasites have complex life cycles, during which they infect a variety of specific cell types that are difficult to access or model in vitro. Even in those cases when host cells are readily available, these are generally terminally differentiated and difficult or impossible to manipulate genetically, which prevents assessing the role of human factors in these diseases. The advent of stem cell technology has opened exciting new possibilities to advance our knowledge in this field. The capacity to culture Embryonic Stem Cells, derive Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells from people and the development of protocols for differentiation into an ever-increasing variety of cell types and organoids, together with advances in genome editing, represent a huge resource to finally crack the mysteries protozoan parasites hold and unveil novel targets for prevention and treatment. Keywords: protozoan parasites; stem cells; induced pluripotent stem cells; organoids; vaccines; treatments Citation: Pance, A. The Stem Cell Revolution Revealing Protozoan 1. Introduction Parasites’ Secrets and Paving the Way towards Vaccine Development. -

Pursuing Effective Vaccines Against Cattle Diseases Caused by Apicomplexan Protozoa

CAB Reviews 2021 16, No. 024 Pursuing effective vaccines against cattle diseases caused by apicomplexan protozoa Monica Florin-Christensen1,2, Leonhard Schnittger1,2, Reginaldo G. Bastos3, Vignesh A. Rathinasamy4, Brian M. Cooke4, Heba F. Alzan3,5 and Carlos E. Suarez3,6,* Address: 1Instituto de Patobiologia Veterinaria, Centro de Investigaciones en Ciencias Veterinarias y Agronomicas (CICVyA), Instituto Nacional de Tecnologia Agropecuaria (INTA), Hurlingham 1686, Argentina. 2Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientificas y Tecnologicas (CONICET), C1425FQB Buenos Aires, Argentina. 3Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology, Washington State University, P.O. Box 647040, Pullman, WA, 991664-7040, United States. 4Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine, James Cook University, Cairns, Queensland, 4870, Australia. 5Parasitology and Animal Diseases Department, National Research Center, Giza, 12622, Egypt. 6Animal Disease Research Unit, Agricultural Research Service, USDA, WSU, P.O. Box 646630, Pullman, WA, 99164-6630, United States. ORCID information: Monica Florin-Christensen (orcid: 0000-0003-0456-3970); Leonhard Schnittger (orcid: 0000-0003-3484-5370); Reginaldo G. Bastos (orcid: 0000-0002-1457-2160); Vignesh A. Rathinasamy (orcid: 0000-0002-4032-3424); Brian M. Cooke (orcid: ); Heba F. Alzan (orcid: 0000-0002-0260-7813); Carlos E. Suarez (orcid: 0000-0001-6112-2931) *Correspondence: Carlos E. Suarez. Email: [email protected] Received: 22 November 2020 Accepted: 16 February 2021 doi: 10.1079/PAVSNNR202116024 The electronic version of this article is the definitive one. It is located here: http://www.cabi.org/cabreviews © The Author(s) 2021. This article is published under a Creative Commons attribution 4.0 International License (cc by 4.0) (Online ISSN 1749-8848). Abstract Apicomplexan parasites are responsible for important livestock diseases that affect the production of much needed protein resources, and those transmissible to humans pose a public health risk. -

Personal Water Treatment Devices by Brenda Land, Sanitary Engineer

United States Department of Agriculture Recreation Forest Service Management National Technology & Development Program June 2007 Tech Tips 2300 0723 1304—SDTDC Personal Water Treatment Devices by Brenda Land, Sanitary Engineer A hiker loosens his pack, kneels beside a babbling brook, and replenishes his canteen. Kids skip rocks across a stream before taking a drink at its inlet. A woman dismounts from her horse and leads it to a pool of clear, refreshing water. What all three scenarios have in common is that the participants are looking for clean, safe drinking water. There was a time when we could assume that water from rivers, creeks, brooks, and springs, especially in the back country, was safe to drink. That assumption is no longer true. Lakes and streams usually contain a variety of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, Figure 1—Back-country rangers may spend several protozoa, fungi, and algae. Most of these occur days in the field. naturally and have little impact on human health. Some microorganisms, however, can cause disease in humans (Frankenberger 2007). For these reasons, obtaining adequate supplies of safe drinking water is a challenge for back- country rangers, trail crews, river rangers, and other employees who spend several days at a time in remote locations (figure 1). Not only is water difficult to find, but it is also heavy and bulky to carry. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, active people should drink 2 to 3 liters of water a day. Following this recommendation, back-country rangers need—on average for a 5-day outing—30 pounds of water; or, stated another way, a person would need 15 1-liter bottles of water for a 5-day stay in the back country (figure 2). -

Cryptosporidiosis: Biology, Pathogenesis and Disease Saul Tzipori A,*, Honorine Ward B

Microbes and Infection 4 (2002) 1047–1058 www.elsevier.com/locate/micinf Current Focus Cryptosporidiosis: biology, pathogenesis and disease Saul Tzipori a,*, Honorine Ward b a Division of Infectious Diseases, Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine, North Grafton, MA 01536, USA b Division of Geographic Medicine/Infectious Diseases, New England Medical Center, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02111, USA Abstract Ninety-five years after discovery and after more than two decades of intense investigations, cryptosporidiosis, in many ways, remains enigmatic. Cryptosporidium infects all four classes of vertebrates and most likely all mammalian species. The speciation of the genus continues to be a challenge to taxonomists, compounded by many factors, including current technical difficulties and the apparent lack of host specificity by most, but not all, isolates and species. © 2002 Éditions scientifiques et médicales Elsevier SAS. All rights reserved. Keywords: Cryptosporidiosis; Cryptosporidium parvum; Diarrhea; Enteric infection; Opportunistic infection 1. Historical perspective occupies within the host cell membrane are the most obvious [6]. Although Cryptosporidium was first described in the Between 1980 and 1993, three broad entities of laboratory mouse by Tyzzer in 1907 [1], the medical and cryptosporidiosis became recognized [7]. The first was the veterinary significance of this protozoan was not fully revelation in 1980 that Cryptosporidium was, in fact, a appreciated for another 70 years. The interest in Cryptospo- common, yet serious, primary cause of outbreaks as well as ridium escalated tremendously over the last two decades, as sporadic cases of diarrhea in certain mammals [6]. From reflected in the number of publications, which increased 1983 onwards, with the onset of the AIDS epidemic, from 80 in 1983 to 2850 currently listed in MEDLINE. -

Slide 1 This Lecture Is the Second Part of the Protozoal Parasites. in This LECTURE We Will Talk About the Apicomplexans SPECIFICALLY the Coccidians

Slide 1 This lecture is the second part of the protozoal parasites. In this LECTURE we will talk about the Apicomplexans SPECIFICALLY THE Coccidians. In the next lecture we will Lecture 8: Emerging Parasitic Protozoa part 1 (Apicomplexans-1: talk about the Plasmodia and Babesia Coccidia) Presented by Sharad Malavade, MD, MPH Original Slides by Matt Tucker, PhD HSC4933 1 Emerging Infectious Diseases Slide 2 These are the readings for this week. Readings-Protozoa pt. 2 (Coccidia) • Ch.8 (p. 183 [table 8.3]) • Ch. 11 (p. 301, 304-305) 2 Slide 3 Monsters Inside Me • Cryptosporidiosis (Cryptosporidum spp., Coccidian/Apicomplexan): Background: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/ Video: http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me- cryptosporidium-outbreak.html http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me-the- cryptosporidium-parasite.html Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii, Coccidian/Apicomplexan) Background: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/ Video: http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me- toxoplasma-parasite.html 3 Slide 4 Learning objectives: Apicomplexan These are the learning objectives for this lecture. coccidia • Define basic attributes of Apicomplexans- unique characteristics? • Know basic life cycle and developmental stages of coccidian parasites • Required hosts – Transmission strategy – Infective and diagnostic stages – Unique character of reproduction • Know the common characteristics of each parasite – Be able to contrast and compare • Define diseases, high-risk groups • Determine diagnostic methods, treatment • Know important parasite survival strategies • Be familiar with outbreaks caused by coccidians and the conditions involved 4 Slide 5 This figure from the last lecture is just to show you the Taxonomic Review apicoplexans. This lecture we talk about the Coccidians. -

Intestinal Coccidian: an Overview Epidemiologic Worldwide and Colombia

REVISIÓN DE TEMA Intestinal coccidian: an overview epidemiologic worldwide and Colombia Neyder Contreras-Puentes1, Diana Duarte-Amador1, Dilia Aparicio-Marenco1, Andrés Bautista-Fuentes1 Abstract Intestinal coccidia have been classified as protozoa of the Apicomplex phylum, with the presence of an intracellular behavior and adaptation to the habit of the intestinal mucosa, related to several parasites that can cause enteric infections in humans, generating especially complications in immunocompetent patients and opportunistic infections in immunosuppressed patients. Alterations such as HIV/AIDS, cancer and immunosuppression. Cryptosporidium spp., Cyclospora cayetanensis and Cystoisospora belli are frequently found in the species. Multiple cases have been reported in which their parasitic organisms are associated with varying degrees of infections in the host, generally characterized by gastrointestinal clinical manifestations that can be observed with diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, malaise and severe dehydration. Therefore, in this review a specific study of epidemiology has been conducted in relation to its distribution throughout the world and in Colombia, especially, global and national reports about the association of coccidia informed with HIV/AIDS. Proposed revision considering the needs of a consolidated study in parasitology, establishing clarifications from the transmission mechanisms, global and national epidemiological situation, impact at a clinical level related to immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals, -

Cryptosporidiosis in Animals and Humans SAUL TZIPORI Attwood Veterinary Research Laboratory, Westmeadows, Victoria 3047, Australia

MICROBIOLOGICAL REVIEWS, Mar. 1983, p. 84-96 Vol. 47, No. 1 0146-0749/83/010084-13$02.00/0 Copyright © 1983, American Society for Microbiology Cryptosporidiosis in Animals and Humans SAUL TZIPORI Attwood Veterinary Research Laboratory, Westmeadows, Victoria 3047, Australia INTRODUCTION................................. 84 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ORGANISM ................................. 84 Classification ................................. 84 Life Cycle ................................. 84 Species Specificity ................................. 87 Diagnosis .................................. 88 Studies on Oocysts .................................. 88 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DISEASE................................. 89 The Disease in Calves................................. 89 The Disease in Lambs ................................. 89 The Disease in Goats ................................. 89 The Disease in Humans ................................. 89 The Infection in Birds ................................ 90 The Infection in Other Species ................................ 90 EXPERIMENTAL CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS ............. ................... 90 Studies with Calf Isolates ................................ 90 Studies with Human Isolates................................ 91 TREATMENT................................ 92 CONCLUSIONS ................................ 92 SUMMARY ................................ 94 LITERATURE CITED ................................ 94 INTRODUCTION CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ORGANISM Classification Cryptosporidium is a protozoan parasite -

Typification of Virulent and Low Virulence Babesia Bigemina Clones by 18S Rrna and Rap-1C

Accepted Manuscript Typification of virulent and low virulence Babesia bigemina clones by 18S rRNA and rap-1c C. Thompson, M.E. Baravalle, B. Valentini, A. Mangold, S. Torioni de Echaide, P. Ruybal, M. Farber, I. Echaide PII: S0014-4894(14)00059-9 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2014.03.016 Reference: YEXPR 6839 To appear in: Experimental Parasitology Received Date: 6 June 2013 Revised Date: 24 February 2014 Accepted Date: 4 March 2014 Please cite this article as: Thompson, C., Baravalle, M.E., Valentini, B., Mangold, A., Torioni de Echaide, S., Ruybal, P., Farber, M., Echaide, I., Typification of virulent and low virulence Babesia bigemina clones by 18S rRNA and rap-1c, Experimental Parasitology (2014), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2014.03.016 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Title: Typification of virulent and low virulence Babesia bigemina clones by 18S rRNA and rap-1c. Thompson, C.1*; Baravalle, M.E.1; Valentini, B.1; Mangold, A.1; Torioni de Echaide, S.1; Ruybal, P.2; Farber, M.2; Echaide, I.1. 1 Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria, Estación Experimental Agropecuaria Rafaela, Ruta 34 km 227, CC 22, CP 2300 Rafaela, Santa Fe, Argentina.