Eyes on the Desert by Carol Kino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dina Wills Minimalist Art I Had Met Minimalism in the Arts Before Larry

Date: May 17, 2011 EI Presenter: Dina Wills Minimalist Art I had met minimalism in the arts before Larry Fong put up the exhibition in the JSMA Northwest Gallery, but I didn’t know it by name. Minimalism is a concept used in many arts - - theater, dance, fiction, visual art, architecture, music. In the early 80s in Seattle, Merce Cunningham, legendary dancer and lifelong partner of composer John Cage, gave a dance concert in which he sat on a chair, perfectly still, for 15 minutes. My husband and I remember visiting an art gallery in New York, where a painting that was all white, perhaps with brush marks, puzzled us greatly. Last year the Eugene Symphony played a piece by composer John Adams, “The Dharma at Big Sur” which I liked so much I bought the CD. I have seen Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” many times, and always enjoy it. I knew much more about theater and music than I did about visual art and dance, before I started researching this topic. Minimalism came into the arts in NYC in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, to scathing criticism, and more thoughtful criticism from people who believed in the artists and tried to understand their points of view. In 1966, the Jewish Museum in NY opened the exhibition “Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculpture” with everyone in the contemporary art scene there, and extensive coverage in media. It included sculpture by Robert Smithson, leaning planks by Judy Chicago and John McCracken, Ellsworth Kelly’s relief Blue Disc. A line of 137 straw-colored bricks on the floor called Lever by Carl Andre. -

ABSOLUTELY Press Kit Aug 25

1 ABSOLUTELY MODERN A NEW Film BY PHILIPPE MORA “Modern paintings are like women, you'll never enjoy them if you try to understand them.” Freddie Mercury PRESS KIT Inquiries: morafilms@ gmail.com https://www.facebook.com/pages/Absolutely- Modern/429822753746917 2 ABSOLUTELY MODERN is "Absolutely funny, fresh and thought- provoking. Philippe Mora at his best." Piotr Czerkawski, Film Critic Wroclaw “..there is a genuine heart and soul to the film that is something of a passion project for Mora.” Laurence Boyce Screen Daily “The creation here (of Lord Steinway) is definitely a masterpiece.” Anna Tatarska FRED Radio, The Festival Insider “Mora’s films break all conventions, combine different styles and are nearly always saturated with rebellious, surrealistic humor.” Adam Kruk Film Critic, New Horizons “Mora tells perhaps one of his most personal stories to date as he examines art and modernism. Mora, who casual fans would most likely know from such films as Communion and cult classic The Return of Captain Invincible, unsurprisingly does not tell the tale with any regard for the norms of convention..” Screen International “Philippe Mora…French Australian director legend.” Der Spiegel May 2013 3 SYNOPSIS OF THE FILM This story of Modernism, muses and the role of sexuality in art are told by famed art critic Lord Steinway. When a soccer player, confronts Steinway as his son, the story takes a modernist twist itself. This comedy hit at the 2013 New Horizons International Film Festival takes the form of a hybrid of fact and fiction about Lord Steinway, the “Method” art critic, making his television show THE EPIC OF CIVILIZATION. -

Michael Heizer Selected Bibliography

G A G O S I A N Michael Heizer Selected Bibliography Selected Books and Catalogues: 2019 Fox, William. Michael Heizer: The Once and Future Monuments. New York: Monacelli Press. 2017 Voorhies, James. Beyond Objecthood: The Exhibition as a Critical Form since 1968. Boston: MIT Press. Celant, Germano and Chiara Costa. Virginia Dwan: Dwan Gallery. Lausanne: Skira. 2015 Fine, Ruth E., Kara Vander Weg and Michael Heizer. Michael Heizer: Altars. New York: Gagosian Gallery. 2014 Cameron, Dan. The Avant-Garde Collection. Newport Beach, CA: Orange County Museum of Art. Kaz, Leonel, ed. Inusitada Coleção De Sylvio Perlstein. São Paolo: Museu de Arte de São Paolo Assis Chateaubriand. 2013 Allen, Gwen L., Pierre Bal Blanc, Claire Bishop, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, Charles Esche, et al. When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013. Milan: Fondazione Prada. 2012 Lippard, Lucy R. and Jeff Khonsary. 4,492,040 (1969–74). Vancouver: New Documents 2010 Jensen, Susanne, Susanne Lenze, and Reinhard Onnasch. “Michael Heizer: Untitled.” In Nineteen Artists. Berlin: El Sourdog Hex; Bielefeld, Germany: Kerber Verlag. 2011 Reifenscheid, Beate. Die Letzte Freiheit: Von den Pionieren der Land-Art der 1960er Jahre bis zur Natur im Cyberspace. Milan: Silvana. 2010 Goldman, Judith. Robert & Ethel Scull: Portrait of a Collection. New York: Acquavella Gallery. Marcoci, Roxana, ed. The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today. New York: Museum Of Modern Art. 2009 Grabner, Roman, Thomas Kellein, and Felicitas von Richthofen. 1968: Die Große Unschuld. Cologne: DuMont. 2008 Semff, Michael. Künstler Zeichnen. Sammler Stiften, 250 Jahre Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München. Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz. Lara, Cathy, ed. -

Academy Initial Study for Reuse, May 24, 2013

INITIAL STUDY ACADEMY MUSEUM OF MOTION PICTURES PROJECT CITY OF LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA MAY 2013 INITIAL STUDY ACADEMY MUSEUM OF MOTION PICTURES PROJECT CITY OF LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Planning Department 200 N. Spring Street, Room 721 Los Angeles, CA 90012 Prepared by: PCR Services Corporation 201 Santa Monica Boulevard Suite 500 Santa Monica, CA 90401 MAY 2013 Table of Contents Page ENVIRONMENTAL CHECKLIST ATTACHMENT A ‐ PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................ A‐1 A. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ A‐1 B. Project Location and Surrounding Uses .................................................................................................................. A‐2 C. Project Background and Existing Conditions ........................................................................................................ A‐5 D. Description of the Project .............................................................................................................................................. A‐7 E. Anticipated Project Approvals .................................................................................................................................. A‐19 ATTACHMENT B: EXPLANATION OF CHECKLIST DETERMINATIONS ............................................................ -

THE STORY of LAND ART a Film by James Crump

VITO ACCONCI CARL ANDRE GERMANO CELANT PAULA COOPER WALTER DE MARIA VIRGINIA DWAN GIANFRANCO GORGONI MICHAEL HEIZER NANCY HOLT DENNIS OPPENHEIM CHARLES ROSS PAMELA SHARP WILLOUGHBY SHARP ROBERT SMITHSON HARALD SZEEMANN LAWRENCE WEINER THE STORY OF LAND ART a film by james crump PRESENTED BY SUMMITRIDGE PICTURES AND RSJC LLC PRODUCED BY JAMES CRUMP EXECUTIVE PRODUCER RONNIE SASSOON PRODUCER FARLEY ZIEGLER PRODUCER MICHEL COMTE EDITED BY NICK TAMBURRI CINEMATOGRAPHY BY ALEX THEMISTOCLEOUS AND ROBERT O’HAIRE SOUND DESIGN AND MIXING GARY GEGAN AND RICK ASH WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY JAMES CRUMP photograph copyright © Angelika Platen, 2014 troublemakers THE STORY OF LAND ART PRESS KIT Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art A film by James Crump Featuring Germano Celant, Walter De Maria, Michael Heizer, Dennis Oppenheim, Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Vito Acconci, Virginia Dwan, Charles Ross, Paula Cooper, Willoughby Sharp, Pamela Sharp, Lawrence Weiner, Carl Andre, Gianfranco Gorgoni, Harald Szeemann. Running time 72 minutes. Summitridge Pictures and RSJC LLC Present a Film by James Crump. Produced by James Crump. Executive Producer Ronnie Sassoon. Producer Farley Ziegler. Producer Michel Comte. Edited by Nick Tamburri. Cinematography by Alex Themistocleous and Robert O’Haire. Sound Design Gary Gegan and Rick Ash. Written and Directed by James Crump. Troublemakers unearths the history of land art in the tumultuous late 1960s and early 1970s. The film features a cadre of renegade New York artists that sought to transcend the limitations of paint- ing and sculpture by producing earthworks on a monumental scale in the desolate desert spaces of the American southwest. Today these works remain impressive not only for the sheer audacity of their makers but also for their out-sized ambitions to break free from traditional norms. -

Size, Scale and the Imaginary in the Work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim

Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim © Michael Albert Hedger A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History and Art Education UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES | Art & Design August 2014 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hedger First name: Michael Other name/s: Albert Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Ph.D. School: Art History and Education Faculty: Art & Design Title: Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Conventionally understood to be gigantic interventions in remote sites such as the deserts of Utah and Nevada, and packed with characteristics of "romance", "adventure" and "masculinity", Land Art (as this thesis shows) is a far more nuanced phenomenon. Through an examination of the work of three seminal artists: Michael Heizer (b. 1944), Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) and Walter De Maria (1935-2013), the thesis argues for an expanded reading of Land Art; one that recognizes the significance of size and scale but which takes a new view of these essential elements. This is achieved first by the introduction of the "imaginary" into the discourse on Land Art through two major literary texts, Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Shelley's sonnet Ozymandias (1818)- works that, in addition to size and scale, negotiate presence and absence, the whimsical and fantastic, longevity and death, in ways that strongly resonate with Heizer, De Maria and especially Oppenheim. -

Centralizing the Mobile: the Los Angeles County Museum of Art's

Centralizing the Mobile: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Outdoor Installations BY KATIE ANTONSSON The Los Angeles County Museum of Art has been struggling with its role in Los Angeles life since its creation in 1961. Originally part of the Los Angeles Museum of Science, History and Art (est. 1910), LACMA branched off and established itself as a separate art museum in 1961, opening its doors to the public in 1965. During the late 80s and early 90s, the museum devoted itself to opening up new buildings and galleries for new acquisitions, which both expanded and fragmented the museum. For its most recent crusade, LACMA strives to become the cultural center of Los Angeles under the tutelage of director Michael Govan. In a county of nine million citizens spread over 4700 square miles, centralization is a near impossible proposition, but Govan’s innovative thinking has helped propel LACMA to its highest status within Los Angeles life yet, commissioning massive outdoor installations to engage an audience and symbolize a city. From its inception, LACMA’s founders determined to make their museum the west coast answer to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. John Walker, a board member during the museum’s early years, explained, “Of course, the Met has a 100-year advantage, but I believe Los Angeles to have the financial resources and the civic enthusiasm to build a great general collection [from] AD 1200 to our own time.”1 With the founding 1 Christopher Knight, "LACMA's Overhaul Is a Work in Progress." Los Angeles Times, 02 Mar. -

The Velvet Underground By: Kao-Ying Chen Shengsheng Xu Makenna Borg Sundeep Dhanju Sarah Lindholm Group Introduction

The Velvet Underground By: Kao-Ying Chen Shengsheng Xu Makenna Borg Sundeep Dhanju Sarah Lindholm Group Introduction The Velvet Underground helped create one of the first proto-punk songs and paved the path for future songs alike. Our group chose this group because it is one of those groups many people do not pay attention to very often and they are very unique and should be one that people should learn about. Shengsheng Biography The Velvet Underground was an American rock band formed in New York City in 1964. They are also known as The Warlocks and The Falling Spikes. Best-known members: Lou Reed and John Cale. 1967 debut album, “The Velvet Underground & Nico” was named the 13th Greatest Album of All Time, and the “most prophetic rock album ever http://t2.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcTpZBIJzRM1H- made” by Rolling Stone in 2003. GhQN6gcpQ10MWXGlqkK03oo543ZbNUefuLNAvVRA Ranked #19 on the “100 Greatest Artists of All Time” by Rolling Stone. Shengsheng Biography From 1964-1965: Lou Reed (worked as a songwriter) met John Cale (Welshman who came to United States to study classical music) and they formed, The Primitives. Reed and Cale recruited Sterling Morrison to play the guitar (college classmate of Reed’s) as a replacement for Walter De Maria. Angus MacLise joined as a percussionist to form a group of four. And this quartet was first named The Warlocks, then The Falling Spikes. Introduced by Michael Leigh, the name “The Velvet Underground” was finally adopted by the group in Nov 1965. Shengsheng Biography From 1965-1966: Andy Warhol became the group’s manager. -

Unit 1 Myself and Others

Grade: 12th Subject: Humanities Teacher: Ms. Jennifer Johnston Date: August 8, 2010 Unit # 3/Title: Art Media and Process Time Frame (calendar and # of weeks): 20 class meetings Standard(s): 1.1 (Aesthetics) All students will use aesthetic knowledge in the creation of and response to dance, music, theater and the visual arts. 1.2 (Creation and Performance) All students will utilize those skills, media, methods and technologies appropriate to each art form in the creation, performance and presentation of dance, music, theater and the visual arts. 1.3 (Elements and Principles of Design) All students will demonstrate an understanding of the elements and principles of dance, music, theater and the visual arts. 1.4 (Critique) All students will develop, apply and reflect upon knowledge of the process of critique. 1.5 (World Cultures, History and Society) All students will understand and analyze the role, development and continuing influence of the arts in relation to the world cultures, history and society. Big Idea(s): 1) SWBAT discuss the process of drawing and painting and identify the art media used in these works in order to discuss how artists translate their ideas into visual forms. 2) SWBAT describe, explain and recognize the indirect art making processes of printmaking, photography, video and digital media in order to compare and contrast these forms and discuss their advances in the art world. 3) SWBAT identify and describe the four major sculptural techniques in order to critique and discuss works based upon the art media and process used. 4) SWBAT explain the functions of architecture and identify the art media and art processes used in order to describe and discuss the evolution of architecture. -

Art Los Angeles Reader ACID INTERIORS | Nº 3 | JANUARY 2017

JANUARY 2017 Art Los Angeles Reader ACID INTERIORS | Nº 3 | JANUARY 2017 Pool The new fragrance by Sean Raspet Available for a limited time at reader.la/pool ART LOS ANGELES READER Art Los Angeles Reader ACID INTERIORS | Nº 3 | JANUARY 2017 Lost Enchantment From the Editor Interior designer Tony Duquette was known for bedazzling style. A short-lived Malibu ranch would have been his crown jewel. Kate Wolf Every single scene in Rainer Werner 1970s black artists’ interventions into public Fassbinder’s newly rediscovered World on a space, to see what rituals and reorientations Wire features two central colors: burnt or- were required for making the city a place ange and emerald blue. Made in 1973, that they could inhabit. And Travis Diehl digs into Infrastructure Sketches era’s cybernetic systems thinking (everything the history of the New York Times’ coverage In the late 1970s, Barbara McCullough and Senga Nengudi exited Ed Ruscha's is related) found an exquisite analogue in the of LA art, diagnosing a host of antipathic, freeway and claimed land under the off-ramps. conspiracy theory of simulation, which mo- boostered biases. Aria Dean tivates the film’s science fiction plot (we’re The theme acid interiors is inspired by stuck in a virtual reality, we just have no idea). William Leavitt’s theatrical obsession with The colors of the interiors seem to prove the mid-century design, his installations of ge- protagonist’s suspicion: in his apartment, his neric sets that deal with the drama of stuff. Pool office, the restaurant, his secretary’s jacket, I am thrilled to present a work Leavitt made A new fragrance made with synthetic compounds. -

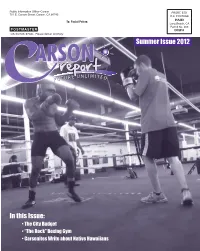

Summmer 2012

Community Connections Meetings A MESSAGE FROM Meetings are in City Hall Elected THE CITY TREASURER and the Community Center OffMiacyoir als The City of Carson has established a Fraud unless otherwise noted, and are open to the public. Jim Dear Hotline to fight fraud and protect Mayor Pro Tem taxpayer’s dollars. The Hotline is an Police & Fire Jobs City Council/Redevelopment option for anyone wishing to anonymously Emergencies 911 Job Clearinghouse Agency 6 p.m., Julie Ruiz-Raber (310) 233-4888 1st and 3rd Tuesdays report illegal or unethical activity on the Animal Control Councilmember part of the City, its officials, employees, Carson Animal Shelter Libraries Citywide Advisory Commission Elito M. Santarina (310) 523-9566 Carson Regional 7 p.m., 2nd Thursday contractors or vendors. The Hotline is (Only when necessary) Birth, Death, (310) 830-0901 Councilmember open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and Marriage Records Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Economic Development Commission Mike A. Gipson interpreters are available in 20 different County Registrar-Recorder (310) 327-4830 8 a.m., 1st Thursday, (562) 462-2137 Community Center Councilmember languages. Parking Lula Davis-Holmes Building Permits Enforcement Environmental Commission Calls placed to the Hotline are confidential (800) 654-7275 Building & Safety, 6:30 p.m., 1st Wednesday City Clerk and handled by a third party vendor. You (310) 952-1766 Parks & Recreation Cultural Arts Commission Donesia Gause do not have to give your name and your (310) 847-3570 6 p.m., 1st Monday Public Transit and City Treasurer call is not recorded through the use of Dial-A-Ride (only when necessary) Post Office Karen Avilla recording devices, caller identification (310) 952-1779 Main No., (800) 275-8777 Human Relations Commission Hearing Impaired 6:00 p.m., 3rd Wednesday City Manager equipment or any other means. -

The Changing Institutional Role of the Art Museum in the United States

Skidmore College Creative Matter MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 MALS 5-17-2014 The Changing Institutional Role of the Art Museum in the United States Evelyn Ramirez-Schultz Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol Part of the Arts Management Commons, Communication Commons, and the Nonprofit Administration and Management Commons Recommended Citation Ramirez-Schultz, Evelyn, "The Changing Institutional Role of the Art Museum in the United States" (2014). MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019. 101. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/101 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the MALS at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Changing Institutional Role of the Art Museum in the United States By Evelyn Ramirez-Schultz Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Degree The Masters Program Skidmore College Saratoga Springs, NY April 2014 Abstract This final project examines the changing role of the art museum in the United States in the last half century. The goal is to show how external and internal forces have influenced a sea change in museums resulting in more engaging and accessible institutions. Through an examination of the forces that motivated these changes, the project explores and compares the two major institutions--the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago--in the areas of audience development and outreach; programming, collections and exhibits and education and outreach.