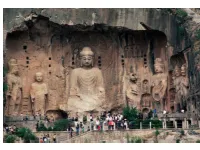

Samantabhadra, Bodhisattva of Great Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Meeting of Minds.Pdf

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Translation:Wang Ming Yee Geshe Thubten Jinpa, and Guo-gu Editing:Lindley Hanlon Ernest Heau Editorial Assistance:Guo-gu Alex Wang John Anello Production: Guo-gu Cover Design:Guo-gu Chih-ching Lee Cover Photos:Guo-gu Kevin Hsieh Photos in the book:Kevin Hsieh Dharma Drum Mountain gratefully acknowledges all those who generously contributed to the publication and distribution of this book. CONTENTS Foreword Notes to the Reader 08 A Brief Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism By His Holiness the 14 th Dalai Lama 22 A Dialogue on Tibetan and Chinese Buddhism His Holiness the 14 th Dalai Lama and Venerable Chan Master Sheng Yen 68 Glossary 83 Appendix About His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama About the Master Sheng Yen 2 Meeting of Minds Foreword n May 1st through the 3rd, 1998, His Holiness the O 14th Dalai Lama and Venerable Chan Master Sheng Yen presented In the Spirit of Manjushri: the Wisdom Teachings of Buddhism, at the Roseland in New York City. Tibet House New York and the Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association sponsored the event, which drew some 2,500 people from all Buddhist traditions, as well as scholars of medicine, comparative religion, psychology, education, and comparative religion from around the world. It was a three-day discourse designed to promote understanding among Chinese, Tibetan, and Western Buddhists. His Holiness presented two-and-a-half days of teaching on Tibetan Buddhism. A dialogue with Venerable Master Sheng Yen, one of the foremost scholars and teachers of Chinese Chan (Zen) Buddhism, followed on the afternoon of the third day. -

The Vows of the Four Great Bodhisattvas

The vows of the four great Bodhisattvas © Thich Nhat Hanh Dear Sangha, today is the 15th January and we are in the New Hamlet. Today we will be studying the vows of the four great Bodhisattvas contained in the chanting of Monday evening. Before we begin, I would like to make a few announcements. On the 4th of February we will be having an ordination ceremony for a number of new novice monks and nuns. That day will be a very nice day. In the early morning we will have the ordination ceremony…. I am now pregnant with these new babies and there is a lot of agitation in my womb because we are not yet sure how many babies I will give birth to. It seems that there are three, there may be four… it is uncertain right now. On the same day, after lunch we will have the ceremony of Lamp Transmission (ordaining a new Dharma Teacher). There is only one nun (the Abbess) from the New Hamlet receiving the Lamp on that day so she will be able to give a long talk. I think that she will be giving a wonderful talk. She may tell us what led her to become a nun, what difficulties has she faced and how she has overcome them. She has been a nun for 24 or 25 years, since she was very young, and she has changed temples and practice centers a lot. Finally she has come to dwell with us here in our practice center, and so I am sure that she will have a lot to share with you. -

AVALOKITESVARA Loka Nat Worship in Myanmar

AVALOKITESVARA Loka Nat Worship in Myanmar A Gift of Dhamma AVALOKITESVARA Loka Nat Tha Worship In Myanmar “(Most venerated and most popular Buddhist deity)” Om Mani Padme Hum.... Page 2 of 12 A Gift of Dhamma Maung Paw, California Bodhisatta Loka Nat (Buddha Image on her Headdress is Amithaba Buddha) Loka Nat, Loka Byu Ha Nat Tha in Myanmar; Kannon, Kanzeon in Japan; Chinese, Kuan Yin, Guanshiyin in Chinese; Tibetan, Spyan-ras- gzigs in Tabatan; Quan-am in Vietnamese Page 3 of 12 A Gift of Dhamma Maung Paw, California Introduction: Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisatta is the most revered Deity in Myanmar. Loka Nat is the only Mahayana Deity left in this Theravada country that Myanmar displays his image openly, not knowing that he is the Mahayana Deity appearing everywhere in the world in a variety of names: Avalokitesvara, Lokesvara, Kuan Yin, Kuan Shih Yin and Kannon. The younger generations got lost in the translation not knowing the name Loka Nat means one and the same for this Bodhisatta known in various part of the world as Avalokitesvara, Lokesvara, Kuan Yin or Kannon. He is believed to guard over the world in the period between the Gotama Sasana and Mettreyya Buddha sasana. Based on Kyaikhtiyoe Cetiya’s inscription, some believed that Loka Nat would bring peace and prosperity to the Goldenland of Myanmar. Its historical origin has been lost due to artistic creativity Myanmar artist. The Myanmar historical record shows that the King Anawratha was known to embrace the worship of Avalokitesvara, Loka Nat. Even after the introduction of Theravada in Bagan, Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, Lokanattha, Loka Byuhar Nat, Kuan Yin, and Chenresig, had been and still is the most revered Mahayana deity, today. -

The Significance of Aspiration of Samantabhadra Prayer (King of Prayers) Edited from a Dharma Lecture by Lama Choedak Rinpoche

The Significance of Aspiration of Samantabhadra Prayer (King of Prayers) Edited from a Dharma Lecture by Lama Choedak Rinpoche Sakya Monastery, Seattle, WA July 3, 2012 Lama Choedak honored and rejoiced in the activities of the founding masters of the Sakya tradition. In particular he honored His Holiness Dagchen Rinpoche’s and the late Dezhung Tulku Rinpoche's vision and the prayers of the sangha bringing forth this beautiful monastery in the United States; and he also mentioned that in Seattle the University of Washington was an important center for Tibetan Studies for many years. Then he began his talk with an invocation to Manjushri, Bodhisattva of Wisdom. The following is an edited version of Lama Choedak’s extensive overview on Samantabhadra’s King of Prayers. The subject matter we have at hand is a very famous prayer, King of Prayers, and we will study it going verse by verse for you to get a gist of the significance of this prayer in order to increase your enthusiasm to do it regularly in the monastery as well as whenever you do your daily prayers. Foremost among the one hundred thousand sutric prayers, this prayer is King. Just like a king is leader of subjects, this prayer is regarded as chief among prayers. Samantabhadra is one of the eight bodhisattvas and Samantabhadra is associated with making offerings and dedicating all the offerings he made to multiply its benefit for sentient beings. So every time we conclude any prayer and teaching session, two or three verses from the King of Prayers often is amongst the dedication prayers. -

The Qianlong Emperor As Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom

object in focus The Qianlong Emperor as Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom Imperial workshop, with face by Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining, 1688–1766) China Qing dynasty, Qianlong reign, mid-18th century Ink, color, and gold on silk 44 3/4 x 25 5/16 in Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment and funds provided by an anonymous donor Freer Gallery of Art, F2000.4 Describe Look at the center of the painting and find the large seated figure wearing red. That is the Qianlong Emperor, who reigned in China from 1735 to 1796. He is shown as an embodiment of Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. The emperor raises his right hand in the gesture of debate or teaching while supporting the wheel of the law in his left. He also holds two stems of lotus blossoms on which lie a sutra and a sword—objects typically associated with Manjushri. Qianlong is pictured among 108 deities (an auspicious number in Buddhism) who represent his Buddhist lineage. In the disk directly above the cloud surrounding the emperor’s image sits his Tibetan Buddhist teacher, Rol-pa’I rdo-rje (1717–1786), with whom he had a very close relationship. The landscape is filled with auspicious clouds. The back- ground is believed to be Wutaishan, a sacred mountain in China. The rich details and bright colors of the painting indicate that it was made for imperial use. The completely accurate depiction of the emperor’s face demonstrates the skill of Giuseppe Castiglione, an Italian Jesuit painter serving at the Qianlong court. Smithsonian Freer Gallery of Art Arthur M. -

Two Pure Land Sutras

The Smaller Pureland Sutra Thus did I hear Seven fine nets, seven rows of trees All of jewels made, sparkling and fine; Once the Buddha at Shravasti dwelt That's why they call it Perfect Bliss In the Jeta Anathapindika garden Together with a multitude of friars There are lakes of seven gems with One thousand two hundred and fifty Water of eightfold merit filled Who were arhats every one And beds of golden sand, As was recognised by all. To which descend on all four sides Gold, silver, beryl and crystal stairs. Amongst them... Shariputra the elder, Great Maudgalyayana, Pavilions and terraces rise above Maha-kashyapa, Gold, silver, beryl and crystal Maha-katyayana, Maha-kausthila, White coral, red pearl and agate gleaming; Revata, Shuddi-panthaka, And in the lakes lotus flowers Nanda, Ananda, Rahula, Large as chariot wheels Gavampati, Pindola Bhara-dvaja, Give forth their splendour Kalodayin, Maha-kapphina, Vakkula, Aniruddha, The blue ones radiate light so blue, and many other disciples The yellow yellow, each similarly great. Red red, white white and All most exquisite and finely fragrant. And, in addition, many bodhisattva mahasattvas... Oh Shariputra, the Land of Bliss Manjushri, prince of the Dharma, Like that is arrayed Ajita, Ganda-hastin, Nityo-dyukta, With many good qualities Together with all such as these And fine adornments. Even unto Shakra the king of devas With a vast assembly of celestials There is heavenly music Beyond reckoning. Spontaneously played And all the ground is strewn with gold. At that time Blossoms fall six times a day Buddha said to Shariputra From mandarava, “Millions of miles to the West from here, The divinest of flowers There lies a land called Perfect Bliss Where a Buddha, Amitayus by name In the morning light, Is even now the Dharma displaying. -

BHZC Archetypes Working

Themes What are archetypes? Introduce some Bodhisattvas in the Mahayana Embodiment of paramita practice Where are they right now? Zen practice and vows Bodhisattva Archetypes Blue Heron Zen Community Kyol Che 2021 talk Gerald Seminatore Archetypes definition Greek archien (to rule) and typos (type) The quintessence or ideal example of a type Object, behavior, idea Synonym: an original model of something (a prototype) Joseph Campbell (1904-1987) The Hero of a Thousand Faces, The Power of Myth, other works. “Shakespeare said that art is a mirror held up to nature. And that's what it is. The nature is your nature, and all of these wonderful poetic images of mythology are referring to something in you." “The idea of the Bodhisattva is the one who out of his realization of transcendence participates in the world. The imitation of Christ is joyful participation in the sorrows of the world.” Bodhisattvas From Sanskrit, literally "one whose essence is perfect knowledge," Bodhi (perfect knowledge) + sattva (reality, being) In the sutras (e.,g, Lotus, Vimalikirti, Avatamsaka) they appear as characters embodying archetypal aspects of Buddhist teaching and psychology (Sages, teachers, heros, companions, guardians, rulers, and other archetypal roles) Often possess some supernatural or divine attributes They cross cultural boundaries, change names, change genders, change forms These archetypes embody common functions/roles in Buddhist practice, and demonstrate myriad possibilities for devotion, imitation, healing, and enlightenment / prajna wisdom. The Bodhisattva’s mission Practice the paramitas in one’s own life to advance on the path Service to others Protect and transmit the Dharma Early Buddhism Beings are on an endless wheel of samsara (rebirths in the suffering world) Once attaining full Enlightenment, the bodhisattva becomes an arhat/arahant. -

The Yoga of the Inseparability of the Guru and Avalokiteshvara

The Source of All Attainments: The Yoga of the Inseparability of the Guru and Avalokiteshvara ༄༅། །害་མ་དང་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་དབ읺ར་མ읺ད་ཀི་讣ལ་ འབ일ར་དངBy일ས་གྲུབ་ʹན་འབྱུང་ཞ His Holiness the읺ས་ Fourteenthབ་བ་བ筴གས་ས 일། ། Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso Translated by Joona Repo FPMT Education Services Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. 1632 SE 11th Avenue Portland, OR 97214 USA www.fpmt.org © 2020 Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Set in Calibri 12/15, Century Gothic, Helvetica Light, Lydian BT, and Monlam Uni Ouchan 2. Page 4, line drawing of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Artist unknown. Technical Note Italics and a small font size indicate instructions and comments found in the Tibetan text and are not for recitation. Text not presented in bold or with no indentation is likewise not for recitation. Words in square brackets have been added by the translator for clarification. For example: This is how to correctly follow the virtuous friend, [the root of the path to full enlightenment]. A Guide to Pronouncing Sanskrit The following six points will enable you to learn the pronunciation of most transliterated Sanskrit mantras found in FPMT practice texts: 1. ŚH and ṢH are pronounced similar to the “sh” in “shoe.” 2. CH is pronounced similar to the “ch” in “chat.” CHH is also similar but is more heavily aspirated. -

MKMC-Brochure-2018.Pdf

Manjushri Kadampa Meditation Centre International Centre for Modern Buddhism and Temple for World Peace September 2018 - August 2019 Everybody Welcome Everyone is welcome at Manjushri Kadampa EXPERIENCE THE PEACE OF Meditation Centre. You can come for an evening class, a meditation MODERN KADAMPA BUDDHISM course, a day visit or to stay for a relaxing break – and for those who are interested there are opportunities to stay as a volunteer or become a full-time resident. Manjushri KMC is the heart of a worldwide network of modern Kadampa Buddhist centres. This worldwide network was founded by Venerable Geshe Kelsang Gyatso Rinpoche (affectionately known as Geshe-la) a world-renowned meditation master who pioneered the introduction of modern Buddhism into contemporary society. Under Venerable Geshe-la's guidance, the centre offers a year-round programme ranging from weekly meditation classes and weekend courses to retreats, in-depth study programmes and international meditation festivals. It is also home to the first Kadampa Temple for World Peace, designed by Venerable Geshe-la, and the headquarters of the New Kadampa Tradition, an international non-profit organization that supports the development of Kadampa Buddhism throughout the world. Tens of thousands of people visit the centre each year for individual, group and educational visits. 2 3 VENERABLE GESHE KELSANG GYATSO RINPOCHE Spiritual Guide and Founder of the New Kadampa Tradition The Founder and Spiritual Guide of Since that time he has devoted himself Manjushri KMC is Venerable Geshe Kelsang tirelessly to giving teachings, composing Gyatso Rinpoche, a contemporary Buddhist books and establishing a global infrastructure meditation master and world-renowned of modern Buddhist Temples and meditation teacher and author. -

Chinese Buddhism Tiantai Buddhism

Buddha Preaching. China, painting from Dunhuang Cave, early 8th c. C.E., ink and colors on silk. Chinese Buddhism Tiantai Buddhism A selection from particular individuals in their own particular situation. This The Lotus Sutra notion of ‘skill-in-means’ emphasized in the Lotus Sütra is one of the key concepts of Mahäyäna Buddhism. (Saddharmapuëòaréka-Sütra) In Chapter Five the famous parable of the medicinal herbs is (Sütra on the Lotus of the True Dharma) used to explain the notion of ‘expedient means’ (upäya). Just as there are many different medicinal herbs from a multitude of [Certainly one of the most important and revered scriptures in different plants to treat all the various sicknesses of human all of East Asia, the Lotus Sütra is most famous for its doctrine beings, the Buddha’s teachings, or Dharma, takes many forms of ekayäna, the “One Vehicle,” which became the distinctive to treat each individual according to his or her needs.] teaching of the Tiantai School of Buddhism as it developed in China (Tendai in Japan). Bewildered by the wide diversity of The Parable of the Medicinal Herbs Indian Buddhist scriptures, and attempting to reconcile the seeming contradictions in the Buddha’s Dharma that arose as At that time the World-Honored One said to a result of the three vehicles of Indian Buddhism, the Hénayäna, Mahakashyapa and the other major disciples: "Excellent, Mahäyäna, and Vajrayäna, the teachers of the Tiantai excellent, Kashyapa. You have given an excellent emphasized that there is really only one vehicle as taught in the description of the true blessings of the Thus Come One. -

Verse 2: Consider Myself As the Lowest Among All

www.khenposodargye.org Verse 2: Consider Myself as the Lowest Among All Whenever I’m in the company of others, I will regard myself as the lowest among all, And from the depths of my heart Cherish others as supreme. Wherever I am and whomever I interact with, I will view myself as the lowest of all and humble myself before them. From the depths of my heart, I will think constantly of benefiting others. By constantly holding others as superior to me, and treating them with reverence and respect, I will tame my pride and arrogance, and hold others above me. a. The perfect examples of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas In Lama Tsongkhapa’s A Commentary on the Fifty Verses of Guru Devotion, there is such a line in the homage verse that says, “Constantly residing above all, but also as a servant to sentient beings.” This is meant as a praise for Manjushri: although he is the teacher of all Buddhas, and is supreme among all sentient beings, Manjushri still attends to all sentient beings like a servant. And this is also the conduct of all the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and great spiritual masters, who, although filled with transmundane merits and virtues, still serve the world as servants. Just as Venerable Longchenpa said in his Finding Comfort and Ease in the Nature of Mind on the Great Perfection, “The guru’s enlightenment is far beyond that of secular beings. In spite of this, he still attends to the world and carries out compassionate activities for the benefit of sentient beings.