The Evolution of the Order Odonata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wing Venation of Odonata

International Journal of Odonatology, 2019 Vol. 22, No. 1, 73–88, https://doi.org/10.1080/13887890.2019.1570876 The wing venation of Odonata John W. H. Trueman∗ and Richard J. Rowe Research School of Biology, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia (Received 28 July 2018; accepted 14 January 2019) Existing nomenclatures for the venation of the odonate wing are inconsistent and inaccurate. We offer a new scheme, based on the evolution and ontogeny of the insect wing and on the physical structure of wing veins, in which the veins of dragonflies and damselflies are fully reconciled with those of the other winged orders. Our starting point is the body of evidence that the insect pleuron and sternum are foreshortened leg segments and that wings evolved from leg appendages. We find that all expected longitudinal veins are present. The costa is a short vein, extending only to the nodus, and the entire costal field is sclerotised. The so-called double radial stem of Odonatoidea is a triple vein comprising the radial stem, the medial stem and the anterior cubitus, the radial and medial fields from the base of the wing to the arculus having closed when the basal sclerites fused to form a single axillary plate. In the distal part of the wing the medial and cubital fields are secondarily expanded. In Anisoptera the remnant anal field also is expanded. The dense crossvenation of Odonata, interpreted by some as an archedictyon, is secondary venation to support these expanded fields. The evolution of the odonate wing from the palaeopteran ancestor – first to the odonatoid condition, from there to the zygopteran wing in which a paddle-shaped blade is worked by two strong levers, and from there through grade Anisozygoptera to the anisopteran condition – can be simply explained. -

Aravalli Range of Rajasthan and Special Thanks to Sh

Occasional Paper No. 353 Studies on Odonata and Lepidoptera fauna of foothills of Aravalli Range, Rajasthan Gaurav Sharma ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 353 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Studies on Odonata and Lepidoptera fauna of foothills of Aravalli Range, Rajasthan GAURAV SHARMA Zoological Survey of India, Desert Regional Centre, Jodhpur-342 005, Rajasthan Present Address : Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata - 700 053 Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata Zoological Survey of India Kolkata CITATION Gaurav Sharma. 2014. Studies on Odonata and Lepidoptera fauna of foothills of Aravalli Range, Rajasthan. Rec. zool. Surv. India, Occ. Paper No., 353 : 1-104. (Published by the Director, Zool. Surv. India, Kolkata) Published : April, 2014 ISBN 978-81-8171-360-5 © Govt. of India, 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED . No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher’s consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which, it is published. The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. PRICE Indian Rs. 800.00 Foreign : $ 40; £ 30 Published at the Publication Division by the Director Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata - 700053 and printed at Calcutta Repro Graphics, Kolkata - 700 006. -

Cumulative Index of ARGIA and Bulletin of American Odonatology

Cumulative Index of ARGIA and Bulletin of American Odonatology Compiled by Jim Johnson PDF available at http://odonata.bogfoot.net/docs/Argia-BAO_Cumulative_Index.pdf Last updated: 14 February 2021 Below are titles from all issues of ARGIA and Bulletin of American Odonatology (BAO) published to date by the Dragonfly Society of the Americas. The purpose of this listing is to facilitate the searching of authors and title keywords across all issues in both journals, and to make browsing of the titles more convenient. PDFs of ARGIA and BAO can be downloaded from https://www.dragonflysocietyamericas.org/en/publications. The most recent three years of issues for both publications are only available to current members of the Dragonfly Society of the Americas. Contact Jim Johnson at [email protected] if you find any errors. ARGIA 1 (1–4), 1989 Welcome to the Dragonfly Society of America Cook, C. 1 Society's Name Revised Cook, C. 2 DSA Receives Grant from SIO Cook, C. 2 North and Central American Catalogue of Odonata—A Proposal Donnelly, T.W. 3 US Endangered Species—A Request for Information Donnelly, T.W. 4 Odonate Collecting in the Peruvian Amazon Dunkle, S.W. 5 Collecting in Costa Rica Dunkle, S.W. 6 Research in Progress Garrison, R.W. 8 Season Summary Project Cook, C. 9 Membership List 10 Survey of Ohio Odonata Planned Glotzhober, R.C. 11 Book Review: The Dragonflies of Europe Cook, C. 12 Book Review: Dragonflies of the Florida Peninsula, Bermuda and the Bahamas Cook, C. 12 Constitution of the Dragonfly Society of America 13 Exchanges and Notices 15 General Information About the Dragonfly Society of America (DSA) Cook, C. -

INTRODUCTION to Dragonfly and Damselfly Watching

Booklet.qxd 11.07.2003 10:59 AM Page 1 TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION TO Dragonfly and Damselfly Watching BY MARK KLYM AND MIKE QUINN Booklet.qxd 11.07.2003 10:59 AM Page 2 Cover illustration by Rob Fleming. Booklet.qxd 11.07.2003 10:59 AM Page 3 Introduction to Dragonfly and Damselfly Watching By Mark Klym and Mike Quinn Acknowledgement This work would not have been possible without the input of Bob Behrstock, John Abbott and Sid Dunkle who provided technical information on the Order Odonata in Texas. This is not the first book about this order of insects, and the work of Sid Dunkle in Dragonflies Through Binoculars was a great help in assembling and presenting the material. Pat Morton was a great help in reviewing the material and keeping the work on track. Booklet.qxd 11.07.2003 10:59 AM Page 4 INTRODUCTION Background Dragonflies and Damselflies are members of the insect order Odonata, derived from the Greek word odonto meaning tooth. They are insects meaning that they have three body regions — a head, a thorax to which their four wings and six legs are attached and an abdomen. They are characterized by two pairs of net-veined wings and large compound eyes. Their wings are not linked together, allowing each wing to operate independently of the others. Damselflies have narrowly rectangular heads and eyes separated by more than their own width while dragonfly eyes are never separated by more than their own width. Both are preda- tors throughout their lives and valuable in destroying mosquitoes, gnats and other insects though they can become pests near beehives and may take other beneficial insects like butterflies. -

Evolution of Dragonflies

Kathleen Tait Biology 501 EVOLUTION OF DRAGONFLIES All life began from a common ancestor. According to most scientists, animal life is thought to have evolved from a flagellated protist. This protist evolved by a cellular membrane folding inward, which became the first digestive system in the Animalia kingdom (Campbell, Reece &, Mitchell, 1999). As time went on, the animalia kingdom became more diversified and the class Arthropoda arose. Arthropods had and still have several characteristics in common. Some of these characteristics include segmented bodies, jointed appendages, compound and/or median eyes, and an external skeleton. Arthropods may breathe through their gills, trachea, body surface or spiracles. Within the order of Arthropods there exits the largest class in the animal kingdom, Insecta. Insects share such common features as three pairs of legs, usually two pairs of wings, a pair of compound eyes, usually one pair of antennae, and a segmented body (head, thorax, abdomen). But from where in time did all of these insects evolve? Wingless insects first appeared in the Devonian period approximately 380 million years ago following the development of the vascular seedless plants. Insects possibly evolved due to the first appearance of seedless vascular plants. These plants were a huge untapped source of food. According to fossil records, insects appeared quickly after plants in order to possibly fill in a new niche. The evolution of insects occurred in four stages (Columbia University Press, 2003). The dragonfly appears in the second stage and therefore this paper will only cover the first two stages. The first stage is known as the Apterygote stage. -

Phylogeny of the Higher Libelluloidea (Anisoptera: Odonata): an Exploration of the Most Speciose Superfamily of Dragonflies

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 45 (2007) 289–310 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogeny of the higher Libelluloidea (Anisoptera: Odonata): An exploration of the most speciose superfamily of dragonflies Jessica Ware a,*, Michael May a, Karl Kjer b a Department of Entomology, Rutgers University, 93 Lipman Drive, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA b Department of Ecology, Evolution and Natural Resources, Rutgers University, 14 College Farm Road, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA Received 8 December 2006; revised 8 May 2007; accepted 21 May 2007 Available online 4 July 2007 Abstract Although libelluloid dragonflies are diverse, numerous, and commonly observed and studied, their phylogenetic history is uncertain. Over 150 years of taxonomic study of Libelluloidea Rambur, 1842, beginning with Hagen (1840), [Rambur, M.P., 1842. Neuropteres. Histoire naturelle des Insectes, Paris, pp. 534; Hagen, H., 1840. Synonymia Libellularum Europaearum. Dissertation inaugularis quam consensu et auctoritate gratiosi medicorum ordinis in academia albertina ad summos in medicina et chirurgia honores.] and Selys (1850), [de Selys Longchamps, E., 1850. Revue des Odonates ou Libellules d’Europe [avec la collaboration de H.A. Hagen]. Muquardt, Brux- elles; Leipzig, 1–408.], has failed to produce a consensus about family and subfamily relationships. The present study provides a well- substantiated phylogeny of the Libelluloidea generated from gene fragments of two independent genes, the 16S and 28S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and using models that take into account non-independence of correlated rRNA sites. Ninety-three ingroup taxa and six outgroup taxa were amplified for the 28S fragment; 78 ingroup taxa and five outgroup taxa were amplified for the 16S fragment. -

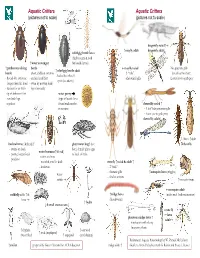

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny - row back legs (type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery buoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

3. the Seven Largest Insect Orders

Virtual Entomology for Master Naturalists 3. The seven largest insect orders Rivanna Master Naturalists 8 April 2020 Linda S. Fink Duberg Professor of Ecology Sweet Briar College The seven largest orders ORDER # families # species in # species worldwide North America worldwide ODONATA (dragonflies and 29 400 > 5000 Paleoptera damselflies) ORTHOPTERA (crickets, katydids, 28 1100 > 10,000 grasshoppers)Exopterygote: orthopteroid HEMIPTERAExopterygote: hemipteroid (true bugs) 133 10,000 > 82,000 COLEOPTERA (beetles) 166 24,000 > 300,000 DIPTERAEndopterygote (flies) 130 17,000 > 100,000 LEPIDOPTERAEndopterygote (butterflies and 135 11,000 > 110,000 moths) Endopterygote HYMENOPTERA (bees, wasps, 90 18,000 > 100,000 ants) Endopterygote PALEOPTERA EXTERNAL WING DEVELOPMENT INTERNAL WING DEVELOPMENT The seven largest orders ORDER # families # species in # species worldwide North America worldwide ODONATA (dragonflies and 29 400 > 5000 Paleoptera damselflies) ORTHOPTERA (crickets, katydids, 28 1100 > 10,000 grasshoppers)Exopterygote: orthopteroid HEMIPTERAExopterygote: hemipteroid (true bugs) 133 10,000 > 82,000 COLEOPTERA (beetles) 166 24,000 > 300,000 DIPTERAEndopterygote (flies) 130 17,000 > 100,000 LEPIDOPTERAEndopterygote (butterflies and 135 11,000 > 110,000 moths) Endopterygote HYMENOPTERA (bees, wasps, 90 18,000 > 100,000 ants) Endopterygote ORDER ODONATA Suborder: Anisoptera (dragonflies) Suborder: Zygoptera (damselflies) ORDER ODONATA Can’t fold wings External wing development Aquatic immatures Aerial adults Predators at all stages ORDER ODONATA -

Factors Affecting Thanatosis in the Braconid Parasitoid Wasp Heterospilus Prosopidis

insects Communication Factors Affecting Thanatosis in the Braconid Parasitoid Wasp Heterospilus prosopidis Mio Amemiya and Kôji Sasakawa * Laboratory of Zoology, Department of Science Education, Faculty of Education, Chiba University, 1-33 Yayoi-cho, Inage-ku, Chiba-shi, Chiba 263-8522, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Thanatosis is an antipredator behavior widely recognized in insects, but our knowledge of this behavior in Hymenoptera is insufficient. We examined the effects of sex, age, temperature, and background color on thanatosis in the parasitoid wasp Heterospilus prosopidis under laboratory conditions, and found that some of these factors have significant effects on thanatosis of this species. Abstract: Thanatosis, also called death feigning, is often an antipredator behavior. In insects, it has been reported from species of various orders, but knowledge of this behavior in Hymenoptera is insufficient. This study examined the effects of sex, age (0 or 2 days old), temperature (18 or 25 ◦C), and background color (white, green, or brown) on thanatosis in the braconid parasitoid wasp Heterospilus prosopidis. Thanatosis was more frequent in 0-d-old individuals and in females at 18 ◦C. The duration of thanatosis was longer in females, but this effect of sex was weaker at 18 ◦C and in 0-d-old individuals. The background color affected neither the frequency nor duration. These results were compared with reports for other insects and predictions based on the life history of this species, and are discussed from an ecological perspective. Keywords: age; background color; death-feigning; sex; temperature; hymenoptera Citation: Amemiya, M.; Sasakawa, K. Factors Affecting Thanatosis in the Braconid Parasitoid Wasp Heterospilus 1. -

Arthropod Survey of 'Öpae 'Ula and Adjacent Summit Areas of the Ko

Arthropod Survey of ‘Öpae ‘ula and Adjacent Summit Areas of the Ko‘olau Mountains, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i David J. Preston , Dan A. Polhemus, Keith T. Arakaki, and Myra K. K. McShane Hawaii Biological Survey, Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawaii, 96817-2704, USA Submitted to Hawaii Department of Land And Natural Recourses Division Of Forestry And Wildlife Hawaii Natural Area Reserve System 1151 Punchbowl Street, Room 325 Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 June 2004 Contribution No.2004-010 to the Hawaii Biological Survey 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................2 METHODS............................................................................................................................................2 COLLECTION SITES .........................................................................................................................2 Table 1: Collection sites .......................................................................................................................3 Figure 1. Sample sites...........................................................................................................................4 RESULTS..............................................................................................................................................4 Table 2: Insects and related arthropods collected from the upper Käluanui drainage, Ko’olau Mountains..............................................................................................................................................6 -

Butterflies and Dragonflies

Spread-winged Skippers WHITES AND SULPHURS METALMARK BUTTERFLIES AND A POCKET GUIDE BUTTERFLIES These skippers are larger than About 14 species in ND of these medium-sized (1.5-2 inch Only one species in ND, the Butterflies belong to the order Lepidoptera, meaning grass skippers and most are Mormon metalmark, and only DRAGONFLIES “scale wings.” It is estimated that up to 20,000 species wingspan) white or yellow butterflies. While species identification brown or gray in color. Eleven is not too difficult, it’s convenient to lump found in the badlands. Adults exist in the world. About 150 species of butterflies have species. feed on rabbit brush and cater- been identified in North Dakota. BRYAN E. REYNOLDS these active butterflies into either “whites” or The insect world is a place to discover and As its name implies the common “yellows.” pillar on wild buckwheat. Common Checkered BRYAN E. REYNOLDS observe thousands of interesting new creatures. Butterflies differ from moths: checkered skipper is common in Skipper Mormon Metalmark It is these small creatures that create the begin- ND and is especially plentiful in Whites BRUSH-FOOTED BUTTERFLIES MOTHS ning to a complex food chain. Without them, the badlands. These caterpillars feed on a variety of BUTTERFLIES many other forms of wildlife would not exist. Smooth, slender bodies Plump, fuzzy bodies plants in the mustard or cabbage family, Grass Skippers These small to large (1-4 inch wingspan) butterflies are From newly hatched ducklings to frogs, toads Thin antennae with a Thicker, more feathery including broccoli and cabbage in your active and colorful. -

Odonata (Insecta) Transcriptomics Resolve Familial Relationships

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.07.191718; this version posted July 7, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. How old are dragonflies and damselflies? Odonata (Insecta) transcriptomics resolve familial relationships 1Manpreet Kohli*, 2Harald Letsch*, 3Carola Greve, 4Olivier Béthoux, 4Isabelle Deregnaucourt, 5Shanlin Liu, 5Xin Zhou, 6Alexander Donath,6Christoph Mayer,6Lars Podsiadlowski, 7Ryuichiro Machida, 8Oliver Niehuis, 9Jes Rust, 9Torsten Wappler, 10Xin Yu, 11Bernhard Misof, 1Jessica Ware 1Department of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA, 2Department for Animal Biodiversity, Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 3LOEWE Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (LOEWE-TBG), Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 4Sorbonne Université, MNHN, CNRS, Centre de recherche sur la Paléontologie – Paris (CR2P), Paris, France,5Department of Entomology, China Agricultural University, 100193 Beijing, People’s Republic of China, 6Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Zentrum für Molekulare Biodiversitätsforschung, Bonn, Germany,7Sugadaira Montane Research Center, University of Tsukuba, Sugadaira Kogen Ueda, Nagano, Japan, 8Department of Evolutionary Biology and Ecology, Institute of Biology I (Zoology), Albert Ludwig University, Freiburg, Germany, 9Natural History Department, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany 10College of Life Sciences, Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing, 401331, China, 11Zoological Research Museum (ZFMK), Bonn University, Bonn, Germany * corresponding author Corresponding authors contact information: *Dr. Manpreet Kohli, [email protected] *Dr. Harald Letsch, [email protected] Summary Dragonflies and damselflies, representing the insect order Odonata, are among the earliest flying insects with living (extant) representatives.