James Feldman | the View from Sand Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chequamegon Bay and Its Communities I Ashland Bayfield La Pointe a Brief History 1659-1883

Chequamegon Bay And Its Communities I Ashland Bayfield LaPointe A Brief Hi story 1659-1883 Chequamegon Bay And Its Communities I Ashland Bayfield La Pointe A Brief History 1659-1883 Lars Larson PhD Emeriti Faculty University of Wisconsin-Whitewater CHEQUAMEGON BAY Chequamegon, sweet lovely bay, Upon thy bosom softly sway. In gentle swells and azure bright. Reflections of the coming night; Thy wooded shores of spruce and pine. Forever hold thee close entwine. Thy lovely isles and babbling rills. Whose music soft my soul enthrills; What wondrous power and mystic hands. Hath wrought thy beach of golden sands. What artist's eye mid painter's brush. Hath caught thy waters as they rush. And stilled them all and then unfurled. The grandest picture of the world— So fair, so sweet to look upon. Thy beauteous bay, Chequamegon. Whitewater Wisconsin 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 The Chequamegon Bay Historians 4 Odes to Chequamegon Bay 7 Introduction 13 Chapter 1—An Overview of Wisconsin History to 1850 26 Chapter 2—Chequamegon Bay and La Pointe 1659-1855 44 Chapter 3—The Second Era of Resource Exploitation 82 Chapter 4—Superior 1853-1860 92 Chapter 5—Ashland 1854-1860 112 Chapter 6—Bayfield 1856-1860 133 Chapter 7—Bayfield 1870-1883 151 Chapter 8—Ashland 1870-1883 186 Chapter 9—The Raikoad Land Grants: Were The Benefits Worth The Cost? 218 Bibliographies 229 Introduction 230 Wisconsin History 23 4 Chequamegon Bay and La Pointe 241 Second Era of Resource Exploitation 257 Superior 264 Ashland 272 Bayfield 293 Introduction 1860-1870 301 Railroad Land Grants 304 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the staffs of the Andersen Library of the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, and the Library of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, mid to the Register of Deeds of Bayfield County, for their indispensable assistance mid support in the preparation of this study. -

USGS 7.5-Minute Image Map for Sand Island OE N, Wisconsin

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR SAND ISLAND OE N QUADRANGLE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WISCONSIN-BAYFIELD CO. 7.5-MINUTE SERIES 91°00' 57'30" 55' 90°52'30" 6 000m 6 6 6 6 6 6 1 750 000FEET 47°07'30" 52 E 53 54 56 57 59 60 47°07'30" 5221 5220000mN 5220 710 000 FEET 5219 5219 5218 5218 5217 5217 Imagery................................................NAIP, January 2010 Roads..............................................©2006-2010 Tele Atlas Names...............................................................GNIS, 2010 5' 5' Hydrography.................National Hydrography Dataset, 2010 Contours............................National Elevation Dataset, 2010 5216 5216 5215 5215 5214 5214 5213 5213 5212 2'30" 2'30" 5211 5211 680 000 FEET 5210 LAKE SUPERIOR 5209 5209 5208 5208000mN APOSTLE ISLANDS NATIONAL LAKESHORE Apostle Islands CHEQUAMEGON12 NATIONAL FOREST Lighthouse Bay T52NSand IslandR5W 47°00' 47°00' 1 720 000FEET 653 654 655 656 657 658 659 660 661000mE 91°00' 57'30" CHEQUAMEGON 55' 90°52'30" 12 ^ Produced by the United States Geological Survey SCALENATIONAL 1:24 000 FOREST ROAD CLASSIFICATION 1 North American Datum of 1983 (NAD83) 3 7 Expressway Local Connector World Geodetic System of 1984 (WGS84). Projection and MN 1 0.5 0 KILOMETERS 1 2 8 5 Ø 1 1 000-meter grid: Universal Transverse Mercator, Zone 15T 1° 54´ WISCONSIN Secondary Hwy Local Road 1000 500 0 METERS 1000 2000 7 10 000-foot ticks: Wisconsin Coordinate System of 1983 (north 34 MILS 6 GN Ramp 4WD 3 zone) 1° 31´ 1 0.5 0 1 7 27 MILS K MILES X Interstate Route US Route State Route 0 This map is not a legal document. -

Amazing Apostle Islands Happy Times Tours & Experiences

Amazing Apostle Islands (Bayfield, WI) Trip Includes: - 3 Nights at the Legendary Waters Resort & Casino with a total of $75 in Legendary Loot (Promotional Play) - Drive through Scenic Northern Wisconsin and enjoy a shopping stop in Minocqua - Visit the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Apostle Islands – Sea Cave Raspberry Island Lighthouse Center - Ferry to Madeline Island Escape from the world for a while. Reconect with - Locally Guided Madeline Island Tour nature and enjoy a vacation you will never forget! - Lunch at the Pub on Madeline Island - Lighthouse & Sea Caves Cruise 4 Days: September 7 – 10, 2021 - Old Rittenhouse Inn Victorian Luncheon Day 1 B, D - Bayfield Guided Tour with a stop at a Enjoy a boxed breakfast as we head North. We will make a shopping stop in scenic Local Farm Minocqua, Wisconsin before continuing our journey through beautiful Northern - Visit Bonnie & Clyde’s Gangster Park Wisconsin. We will make a stop at the Northern Great Lakes Visitor Center to learn - Motorcoach Transportation and the a little more about this area before an included dinner is included at a local place known for their Prime Rib and Whitefish. We will arrive at the Legendary Waters Services of a Happy Times Tour Director Resort & Casino for a 3 night stay and all rooms have a beautiful view. Everyone - 7 Meals will receive a total of $75 in Legendary Loot (promotional play) during your stay at Departure Times & Locations: the Legendary Waters Resort & Casino. 6:30am Depart College Ave NE P&R (estimated return at 7:30pm) Day 2 B, L 7:00am Depart Watertown Plank P&R Today, we will board the Madeline Island Ferry to Madeline Island, where the (estimated return at 7:00pm) sandy shores and magnificent lake air beckons. -

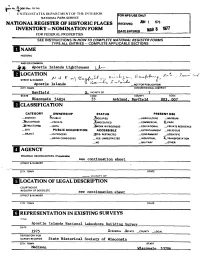

Dname Classification Hlocation of Legal

ft*m No.jit-^06 (Rev. 10-74) ! UNlTEDSTATESDtPARTMhNTOFTHt INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES 1 1976 INVENTORY ~ NOMINATION FORM MAR 8 1977 QAT6 ENTERED FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS DNAME HISTORIC AND/OR COMMON Apostle Islands Lighthouses QLOCATION *•• A/ 4 F c>s. (i STREET& NUMBER ' • , ) uV^.S: Apostle Islands "*"" —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Bavfield X_ VICINITY OF 7 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Wisconsin 54814 55 Ashland. Bavfield 003. 007 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE jr —DISTRICT ^PUBLIC JfecCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM JJBUILDING(S) —PRIVATE UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X-PARK .^STRUCTURES —BOTH JSwORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS JfrES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL X-TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER [AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: IHtpplittbltt see continuation sheet STREET* NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC see continuation sheet STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Apostle Islands National Lakesbore Building Survey DATE 1975 XFEDERAL JJSTATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS State Historical Society of Wisconsin CITY. TOWN STATE Madison Wisconsin [DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT X-DETERIORATED JfUNALTERED XORIGINALSITE _RUINS JtALTERED XMOVED nATP J^FAIR _UNEXPOSED (Michigan Island Tower) DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Apostles Islands lighthouses Include five complexes of buildings totaling approximately 34 acres of land. The lighthouses are all located in a distinct archipelago near the southwestern tip of Lake Superior off the northeastern tip of Bayfield County's peninsula. -

2016 Around the Archipelago

National Park Service Apostle Islands National Lakeshore U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper - 2016 Around the Archipelago Centennial Events The National Park Service Turns 100 at Apostle Islands IT WAS KIND OF A ROCKY START. IN THE 44 YEARS National Lakeshore following the establishment of Yellowstone as the world’s first “national park” in 1872, the United States authorized 34 additional Apostle Islands National Lakeshore has national parks and monuments, but no single agency provided planned a number of special events to unified management of the varied federal park lands. celebrate the NPS Centennial including: On August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the act Chequamegon Bay Birding and Nature creating the National Park Service (NPS), a new federal bureau in Festival. May 19-21. The 10th annual the Department of the Interior responsible for protecting the 35 festival will include numerous guided trips national parks and monuments then managed by the department in the park and a keynote presentation on and those yet to be established. This “Organic Act” states that the NPS Centennial by assistant chief of “the Service thus established shall promote and regulate the use interpretation Neil Howk. of the Federal areas known as national parks, monuments and Mural Dedication in Ashland. June reservations…by such means and measures as…to conserve the 25th at 11 am. A permanent, outdoor, scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein public mural celebrating the Apostle Islands and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and National Lakeshore will be completed and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of dedicated in a public ceremony in the park’s future generations.” newest gateway community of Ashland, WI. -

Rewilding the Islands: Nature, History, and Wilderness at Apostle

Rewilding the Islands: Nature, History, and Wilderness at Apostle Islands National Lakeshore by James W. Feldman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2004 © Copyright by James W. Feldman 2004 All Rights Reserved i For Chris ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii INTRODUCTION Wilderness and History 1 CHAPTER ONE Dalrymple’s Dream: The Process of Progress in the Chequamegon Bay 20 CHAPTER TWO Where Hemlock came before Pine: The Local Geography of the Chequamegon Bay Logging Industry 83 CHAPTER THREE Stability and Change in the Island Fishing Industry 155 CHAPTER FOUR Consuming the Islands: Tourism and the Economy of the Chequamegon Bay, 1855-1934 213 CHAPTER FIVE Creating the Sand Island Wilderness, 1880-1945 262 CHAPTER SIX A Tale of Two Parks: Rewilding the Islands, 1929-1970 310 CHAPTER SEVEN Conclusion: The Rewilding Dilemma 371 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 412 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS *** One of the chief advantages of studying environmental history is that you can go hiking, camping, and exploring in beautiful places and call it research. By choosing the history of the Apostle Islands for a dissertation topic, I even added kayaking and sailing to my list of research activities. There were many more hours spent in libraries, but those weren’t quite as memorable. All graduate students should have topics like this one. As I cast about for a dissertation topic, I knew that I wanted a place-based subject that met two requirements: It needed to be about a place to which I had a personal connection, and it needed to apply to a current, ongoing policy question or environmental issue. -

Wisconsin Historic Properties

Wisconsin Historic Properties LaPointe Indian Cemetery Trout Point Logging Camp Adams County Confidential Address Restricted Preston, Town of (NRHP 08-03-77) (NRHP 12-16-88) Roche-a-Cri Petroglyphs (SRHP --) (SRHP 01-01-89) Roche-A-Cri State Park, LUCERNE (Shipwreck) Winston-Cadotte Site Friendship, 53934 Lake Superior restricted (NRHP 05-11-81) (NRHP 12-18-91) (NRHP 12-16-05) Friendship (SRHP --) (SRHP 09-23-05) Adams County Courthouse Manitou Camp Morse, Town of Confidential 402 Main St. Copper Falls State Park (NRHP 01-19-83) (NRHP 03-09-82) State Highway 169, 1.8 miles (SRHP --) (SRHP 01-01-89) northeast of Mellen Marina Site (NRHP 12-16-05) Ashland County Confidential (SRHP 09-23-05) (NRHP 12-22-78) Sanborn, Town of Jacobs, Town of (SRHP --) Glidden State Bank Marquette Shipwreck La Pointe Light Station Long Island in Chequamagon Bay 216 First Street 5 miles east of Michigan ISland, (NRHP 08-04-83) (NRHP 03-29-06) Lake Superior (SRHP 01-01-89) (SRHP 01-20-06) (NRHP 02-13-08) Marion Park Pavilion (SRHP 07-20-07) Ashland Marion Park Moonlight Shipwreck Ashland County Courthouse (NRHP 06-04-81) 7 miles east of Michigan Island, 201 W. 2nd St. (SRHP 01-01-89) Lake Superior (NRHP 03-09-82) La Pointe, Town of (NRHP 10-01-08) (SRHP 01-01-89) (SRHP 04-18-08) Ashland Harbor Breakwater Apostle Islands Lighthouses Morty Site (47AS40) Light N and E of Bayfield on Michigan, Confidential breakwater's end of Raspberry, Outer, Sand and (NRHP 06-13-88) Chequamegon Bay Devils Islands (SRHP --) (NRHP 03-01-07) (NRHP 03-08-77) (SRHP --) (SRHP 01-01-89) NOQUEBAY (Schooner--Barge) Bass Island Brownstone Shipwreck Site Ashland Middle School Company Quarry Lake Superior 1000 Ellis Ave. -

2019-2020 Wisconsin Blue Book: Historical Lists

HISTORICAL LISTS Wisconsin governors since 1848 Party Service Residence1 Nelson Dewey . Democrat 6/7/1848–1/5/1852 Lancaster Leonard James Farwell . Whig . 1/5/1852–1/2/1854 Madison William Augustus Barstow . .Democrat 1/2/1854–3/21/1856 Waukesha Arthur McArthur 2 . Democrat . 3/21/1856–3/25/1856 Milwaukee Coles Bashford . Republican . 3/25/1856–1/4/1858 Oshkosh Alexander William Randall . .Republican 1/4/1858–1/6/1862 Waukesha Louis Powell Harvey 3 . .Republican . 1/6/1862–4/19/1862 Shopiere Edward Salomon . .Republican . 4/19/1862–1/4/1864 Milwaukee James Taylor Lewis . Republican 1/4/1864–1/1/1866 Columbus Lucius Fairchild . Republican. 1/1/1866–1/1/1872 Madison Cadwallader Colden Washburn . Republican 1/1/1872–1/5/1874 La Crosse William Robert Taylor . .Democrat . 1/5/1874–1/3/1876 Cottage Grove Harrison Ludington . Republican. 1/3/1876–1/7/1878 Milwaukee William E . Smith . Republican 1/7/1878–1/2/1882 Milwaukee Jeremiah McLain Rusk . Republican 1/2/1882–1/7/1889 Viroqua William Dempster Hoard . .Republican . 1/7/1889–1/5/1891 Fort Atkinson George Wilbur Peck . Democrat. 1/5/1891–1/7/1895 Milwaukee William Henry Upham . Republican 1/7/1895–1/4/1897 Marshfield Edward Scofield . Republican 1/4/1897–1/7/1901 Oconto Robert Marion La Follette, Sr . 4 . Republican 1/7/1901–1/1/1906 Madison James O . Davidson . Republican 1/1/1906–1/2/1911 Soldiers Grove Francis Edward McGovern . .Republican 1/2/1911–1/4/1915 Milwaukee Emanuel Lorenz Philipp . Republican 1/4/1915–1/3/1921 Milwaukee John James Blaine . -

Apostle Islands NL Wilderness Newspaper Article

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper of Around the Archipelago Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Spring, Summer, Fall 2005 New Apostle Islands Wilderness Honors - Gaylord Nelson Wilderness ...there is not another collection of islands of this Management significance within the continental boundaries of the Now that the Gaylord Nelson Wilderness United States. I think it is tremendously important Area has been officially established, what that this collection of islands be preserved.” impacts will that have on how the National - Gaylord Nelson Park Service (NPS) manages the area? Since it is NPS policy to assure that With the stroke of a pen, on December 8, 2004, President management actions do not diminish the George W. Bush approved legislation designating 80% of the land wilderness suitability of an area possessing area of Wisconsin’s Apostle Islands National Lakeshore as wilderness characteristics pending federally protected wilderness. The new wilderness area – Congressional action, most of the Apostle Wisconsin’s largest by far – honors former Governor and U.S. Islands National Lakeshore has been Senator, Gaylord Nelson. This new addition to the National managed essentially as wilderness since Wilderness Preservation System will be known as the Gaylord 1989. This means that changes will be Nelson Wilderness. The designation guarantees that the present nearly imperceptible. One tangible change management style of Apostle Islands National Lakeshore will be will be the removal of picnic tables from 13 maintained in the future - emphasizing continued motorized boat campsites located in the new wilderness access to the mostly-wild islands, but no motorized travel on the area, since NPS policy precludes picnic tables in wilderness. -

Comparing Ship-Based to Multi-Directional Sled-Based Acoustic Estimates of Pelagic Fishes in Lake Superior

Comparing Ship-based to Multi-Directional Sled-based Acoustic Estimates of Pelagic Fishes in Lake Superior A Thesis SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ryan Christopher Grow IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Dr. Thomas R. Hrabik May, 2019 © Ryan C. Grow 2019 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank God whose blessings have shaped me into who I am today; specifically, for my passion for science and nature. I am extremely grateful to my advisor Dr. Tom Hrabik for his guidance and support throughout my graduate experience and on my thesis. I would also like to thank my committee members Dr. Ted Ozersky, Dr. Joel Hoffman, and Dr. Jared Myers for their contributions and advice in the process of completing my thesis. I am also grateful to Dan Yule for all of his support and guidance throughout my project, and for bringing me up to speed on the sled-based acoustics. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr. Bryan Matthias for always having his door open to provide guidance on statistics and R coding, and for providing feedback on my thesis. Additionally, I would like to thank the crew of the USGS R/V Kiyi: Captain Joe Walters, Keith Peterson, Chuck Carrier, Abigail Granit, Lori Evrard, Caroline Rosinski, and Jacob Czarnik-Neimeyer; as well as Jamie Dobosenski, and Ian Harding for their help in data collection. I am also thankful to the UMD IBS students and faculty for their comradery and support in my time at UMD. -

Apostle Islands Lighthouses QLOCATION *•• A/ 4 F C>S

ft*m No.jit-^06 (Rev. 10-74) ! UNlTEDSTATESDtPARTMhNTOFTHt INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES 1 1976 INVENTORY ~ NOMINATION FORM MAR 8 1977 QAT6 ENTERED FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS DNAME HISTORIC AND/OR COMMON Apostle Islands Lighthouses QLOCATION *•• A/ 4 F c>s. (i STREET& NUMBER ' • , ) uV^.S: Apostle Islands "*"" —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Bavfield X_ VICINITY OF 7 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Wisconsin 54814 55 Ashland. Bavfield 003. 007 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE jr —DISTRICT ^PUBLIC JfecCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM JJBUILDING(S) —PRIVATE UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X-PARK .^STRUCTURES —BOTH JSwORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS JfrES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL X-TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER [AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: IHtpplittbltt see continuation sheet STREET* NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC see continuation sheet STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Apostle Islands National Lakesbore Building Survey DATE 1975 XFEDERAL JJSTATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS State Historical Society of Wisconsin CITY. TOWN STATE Madison Wisconsin [DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT X-DETERIORATED JfUNALTERED XORIGINALSITE _RUINS JtALTERED XMOVED nATP J^FAIR _UNEXPOSED (Michigan Island Tower) DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Apostles Islands lighthouses Include five complexes of buildings totaling approximately 34 acres of land. The lighthouses are all located in a distinct archipelago near the southwestern tip of Lake Superior off the northeastern tip of Bayfield County's peninsula. -

Wisconsin's Great Island Escape!

Largest of the Apostle Islands. Lake Superior. Wisconsin. Madeline Island 2O2O2O2O VisitorVisitor GuideGuide Ferry Schedule and Map 715.747.28o1 | madelineisland.com N Devils North Twin Island Island South Madeline Island Chamber of Commerce Rocky Cat Outer Bear Twin Island Island MADELINE Island Island Island www.madelineisland.com 715-747-28o1 YorkIsland | IronwoodIsland Sand Island Otter Island ISLAND Raspberry Manitou Island come over. Eagle Island Island is Oak Stockton Island Island N Shore Rd Gull 90 miles Island 13 K Hermit N from Duluth Island Michigan 13 Red Cliff Basswood Island 220 miles from13 Cornucopia Island MinneapolisHerbster C Bayfield Kron-Dahlin Ln H Madeline WISCONSIN Island 320 miles 13 from Madison La Pointe Amnicon Point 450 miles Long Island Lake Superior School House Road C Scale: from Chicago Chequamegon Chippewa Trail Washburn Chequamegon Point 0 1 2 3 4 5 Bay Anderson Lane 13 Umbrage Road Some visitors have come since childhood2 Odanahand others G Ashland have just discovered the turn-of-the-century2 charm Blacktop Big Bay Rd (County H) Bike Lane on Shoulder of Bayfield on the mainland and La Pointe Blvd Benjamin’s Gravel Road on Madeline Island. One of 22 Apostle North Shore Rd Hiking Trail Islands, Madeline’s population ranges Big Bay Town Park from 220 in the winter to 2,500 in the summer. Ferries cross from Big Bay In 1659, the explorers and fur traders spring breakup until late winter with Groseilliers and Radisson came to Chequamegon passengers on foot or with Bay and for 150 years, it was an outpost for French, British and American fur traders.