160329 DCU Master

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIOCHAIN Is a Full Participating Member of the Press Council of Ireland and Supports the Office of the Press Ombandsman

SÍOCHÁIN GSRMA TRIBUTES TO A FALLEN HERO DETECTIVE GARDA COLM HORKAN (13 Dec 1970 – 17 June 2020) Autumn 2020 WINTER 2015 ISSN 1649-5896 ISSN 1649-5896 www.gardaretired.com SCAN QR CODE FOR MEMBERS’ AREA THINKING HOME IMPROVEMENT? A Home Improvement loan will brighten your day. Up to €75,000 - available now and approved within 24 hrs. 4.25% variable (4.33% APR). EMAIL: WEB: [email protected] www.straphaelscu.ie Lending criteria, terms and conditions apply. Credit facilities are subject to repayment capacity and financial status and are not available to persons under 18 years of age. Security may be required. A typical €30,000 five year loan with a variable interest rate of 4.25% and 4.33% APR (Annual Percentage Rate), where the APR does not vary during the term, would have monthly repayments of €555.89 and the total cost of credit (the total amount repayable less the amount of the loan) would be €3,353.20. Warning - If you do not meet the repayments on your credit agreement, your account will go into arrears. This may affect your credit rating, which may limit your ability to access credit in the future. EDITORIAL COMMENT GSRMA’S MANTRA FOR PENSION PARITY We continue to strive for our three-fold requirements of Parity, Representation and Restoration, which must form part of our mantra as talks for a new successor to the PSSA get under way. The economic situation in Ireland and globally will have a part to play post Covid-19 and our demands and our mantra must remain in place. -

SUMMER 2016 Www

Box Office 0504 90204 SUMMER 2016 www.thesourceartscentre.ie www. thesourceartscentre.ie The Source Arts Centre Summer 2016 Programme The days are finally getting brighter and a little warmer so it’s a good time to get out of the house and come to the Source to see a few events. We’ve got a good selection of musical acts – the highly tipped Dublin songwriter Anderson who became famous for selling his album door-to-door, arrives for a solo show; Cork-born songwriter Mick Flannery presents his new album in another solo gig and we’ve opened up the auditorium for some tribute shows like Live Forever and Roadhouse Doors to give a more concert-type feel, so check these out on our brochure. Legendary Manchester poet John Cooper Clarke comes to visit us on May 4th; we have theatre with ‘The Corner Boys’, God Bless The Child’ and Brendan Balfe reminisces about the golden days of Irish radio in early June. Summer is a time for the kids and again we have a series of arts workshops and classes running over the summer months to keep them all occupied. Keep a lookout for our website: www.thesourceartscentre.ie for updates to our programme as we regularly add new events. Addtionally we put updates on our Facebook page. If you wish to be included on our mailing list, just get in contact with us at: boxoffice @sourcearts.ie We look forward to seeing you at The Source during the summer Brendan Maher Artistic Director Buy online Stef Hans open at You can choose your preferred seat when you The Source Arts Centre buy online 24/7 via your laptop, tablet or smart Fine day-time cuisine from award winning phone at www.thesourceartscentre.ie. -

Free, M. (2015) Don't Tell Me I'm Still...Pdf

Pre-publication version. This is scheduled for publication in the journal Critical Studies in Television, Vol. 10, Summer 2015. It should be identical to the published version, but there may be minor adjustments (typographical errors etc.) prior to publication. Title: ‘Don’t tell me I’m still on that feckin’ island’: Migration, Masculinity, British Television and Irish Popular Culture in the Work of Graham Linehan Author: Marcus Free, Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick – [email protected] Abstract The article examines how, through such means as interviews and DVD commentaries, television situation comedy writer Graham Linehan has discursively elaborated a distinctly migrant masculine identity as an Irish writer in London. It highlights his stress on how the working environment of British broadcasting and the tutelage of senior British broadcasters facilitated the satirical vision of Ireland in Father Ted. It focuses on the gendering of his narrative of becoming in London and how his suggestion of interplays between specific autobiographical details and his dramatic work have fuelled his public profile as a migrant Irish writer. Graham Linehan has written and co-written several situation comedies for British television, including Father Ted (with Arthur Mathews – Channel 4, 1995-98); Black Books (with Dylan Moran – Channel 4, 2000-2004 (first series only)); The IT Crowd (Channel 4, 2006- 13); and Count Arthur Strong (with Steve Delaney – BBC, 2013-15). Unusually, for a television writer, he has also developed a significant public profile in the UK and Ireland through his extensive interviews and uses of social media. Linehan migrated from Dublin to London in 1990 and his own account of his development as a writer stresses his formation through the intersection of Irish, British and American influences. -

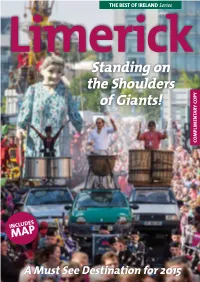

Limerick Guide

THE BEST OF IRELAND Series LimerickStanding on the Shoulders of Giants! COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY INCLUDES MAP A Must See Destination for 2015 Limerick Guide Lotta stories in this town. This town. This old, bold, cold town. This big town. This pig town. “Every house a story…This gets up under your skin town…Fill you with wonder town…This quare, rare, my ho-o-ome is there town. Full of life town. Extract from Pigtown by local playwright, Mike Finn. Editor: Rachael Finucane Contributing writers: Rachael Finucane, Bríana Walsh and Cian Meade. Photography: Lorcan O’Connell, Dave Gaynor, Limerick City of Culture, Limerick Marketing Company, Munster Images, Tarmo Tulit, Rachael Finucane and others (see individual photos for details). 2 | The Best Of Ireland Series Limerick Guide Contents THE BEST OF IRELAND Series Contents 4. Introducing Limerick 29. Festivals & Events 93. Further Afield 6. Farewell National 33. Get Active in Limerick 96. Accommodation City of Culture 2014 46. Family Fun 98. Useful Information/ 8. History & Heritage Services 57. Shopping Heaven 17. Arts & Culture 100. Maps 67. Food & Drink A Tourism and Marketing Initiative from Southern Marketing Design Media € For enquiries about inclusion in updated editions of this guide, please contact 061 310286 / [email protected] RRP: 3.00 No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the publishers. © Southern Marketing Design Media 2015. Every effort has been made in the production of this magazine to ensure accuracy at the time of publication. The editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions, or for any alterations made after publication. -

Linguistic and Cultural Changes Throughout the History of the Eurovision Song Contest

Linguistic and cultural changes throughout the history of the Eurovision Song Contest Trabajo de Fin de Grado Lenguas Modernas y Traducción Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Written by: Sergio Lucas Rojo Tutored by: Irina Ursachi July 2020 Abstract This paper aims to clarify some of the linguistic problems that have arisen in recent years at the Eurovision Song Contest, one of the most important music events in the world. Through an exhaustive bibliographic review and the individual analysis of a large number of entries, it is concluded that linguistic diversity, an identifying feature of the show in the past, has been reduced by establishing a rule that does not oblige artists to sing in the language of the country they represent. English has taken over the reins of this annual competition, although there is still room for the traditional and the ethnic. The research that has been carried out is intended to serve as a reference for all Eurovision followers who wish to expand their knowledge. It also attempts to clarify concepts such as “linguistic diversity”, “identity” and “culture”, which can be extrapolated to other fields of knowledge. It must be noted that not only have linguistic issues been dealt with, but there are references to all the factors involved in the contest. However, it is those phenomena related to languages that form the backbone of the work. Key words: Eurovision Song Contest, languages, culture, identity, Europe, music. Resumen Este trabajo responde a la necesidad de aclarar algunos problemas lingüísticos que han surgido en los últimos años en el Festival de Eurovisión, uno de los eventos musicales más importantes del mundo. -

A Fully Integrated Smart Public Information Ecosystem - SEE PAGE 26

ISSUE 11 | DECEMBER 2020 WWW.RAILEXPRESS.COM.AU A fully integrated Smart Public Information ECOsystem - SEE PAGE 26 SYSTRA's approach on Mark Campbell takes Improving safety culture Grand Paris Express over the reins at ARTC on megaprojects PAGE 34 PAGE 52 PAGE 92 SUPPORTED BY: RailGallery-Ad-2020-June.pdf 1 18/06/2020 12:47:04 PM MELVELLE EQUIPMENT Transport and industrial marketing The Rail Electric Equipment Specialists C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The world is changing, are you ready? Melvelle Equipment is a specialist supplier of railway maintenance equipment. We offer in-house design and manufacturing to help our customers improve their safety and productivity. With emerging competitors, changes in government policies and Since 1982, Melvelle have been offering small track increasing competition for talent, we must build marketing that enhances maintenance solutions for the insertion and removal of track brand, positions the organisation and helps increase resilience to fasteners as well as welding equipment, overhead wiring, change and disruption. ballast regulating and track geometry. We help you evolve to harness new opportunities, overcome different Our product offering has now grown to include battery challenges and enable your ongoing success. operated equipment and are distributors for international brands which include: Rail Products UK (MEWP and Cranes), Knox Kershaw, Abtus, Permaquip, Rotabroach, Enerpac, Sola Track gauges, MK Tools ballast Tyne. Knowledge of Think like Stunning the industry our clients results Our reliable, purpose -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. TA Trace Adkins=American country music Tatyana Ali=American actress, singer=189,828=14 singer=75,397=34 Tracey Adams=American actress=51,363=69 Thomas Anders+Stooges=Singer, composer, Traci Adell=American, Model=27,406=138 producer=13,843=176 Tehmeena Afzal=American, Model Tom Araya=Bassist and Vocalist in (Adult/Glamour)=19,212=188 Slayer=12,284=192 Trini Alvarado=American, Actress=11,871=266 Tim Armstrong=American, Musician=10,617=220 Tori Amos=American singer=47,293=74 Troy Aikman=All-American college football player, Teresa Ann+Savoy=British, Actress=19,452=184 professional football player, quarterback, College Football Hall of Fame member=67,868=39 Taís Araújo=Brazilian actress=32,699=109 Travis Alexander=American, Victim=9,178=243 Tina Arena=Australian, Personality=30,067=126 Tim Allen=Voice-over artist, character actor, Tichina Arnold=American, Actress=59,349=60 comedian=7,902=263 Taylor Atelian=American actress=64,061=54 Trace Ayala+Pistols=American, Fashion Thayla Ayala=Actress=12,284=260 Designer=12,100=196 ……………… Twin Atlantic COMPLETEandLEFT Tina Arena TA,Taro Aso Tori Amos TA,Taylor Abrahamse Tiffany Alvord TA,Tim Allen Tonight Alive TA,Tom Arnold Tommy ,Aaron ,Golf ,Winner, 1973 Masters Tournament TA,Tori Amos Trace ,Adkins ,Country Musician ,Ladies Love Country Boys TA,Tracy Austin Theodor ,Adorno ,Philosopher ,Dialectic of Enlightenment TA,Troy Aikman Troy ,Aikman ,Football ,Cowboys all-time passing yards leader Todd ,Akin ,Politician ,Congressman, Missouri 2nd Tony ,Alamo ,Religion ,Tony Alamo Ministries -

BBC-Year-Book-1986.Pdf

'A Annua www.americanradiohistory.com www.americanradiohistory.com BBC Handbook 1986 Incorporating the Annual Report and Accounts 1984-85 British Broadcasting Corporation www.americanradiohistory.com i Published by the British Broadcasting Corporation 35 Marylebone High Street, London W 1 M 4AA ISBN 0 563 20448 6 First published 1985 © BBC 1985 Printed in England by Jolly & Barber Ltd, Rugby www.americanradiohistory.com Contents Engineering 76 Part One: Transmission 77 & Television production 78 Annual Report Radio production 80 1984 Research and development 80 Accounts -5 Recruitment 82 Training 82 Personnel 84 Appointments, recruitment, training 84 Foreword Mr Stuart Young (Chairman) v Consultancy 86 Board of Governors viii Occupational health 86 Employee relations 86 Board of Management ix Legal matters 87 Division 87 Introductory 1 Central Services Programmes 5 Commercial activities 89 Television 5 Publications 89 Radio 14 BBC Enterprises Ltd 90 The News Year 23 BBC Co- productions 96 Broadcasting from Parliament 27 Direct Broadcasting by Satellite 97 Religious broadcasting 30 National Broadcasting Councils 99 Educational broadcasting 33 Scotland 99 Programme production in the Regions 44 Wales 108 Bristol 44 Northern Ireland 115 Pebble Mill 48 Manchester 50 Audit Report for the BBC 121 The English TV Regions 51 Balance Sheet and Accounts - Home Services BBC Data 54 and BBC Enterprises Ltd 122 Balance Sheet and Accounts - The BBC and its audiences 56 Open University 138 Broadcasting research 57 Public reaction 60 Public meetings 64 -

Discover a Vibrant City and County! Limerick Guide

THE BEST OF IRELAND Series Limerick COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY INCLUDES MAP Discover a Vibrant City and County! Limerick Guide Lotta stories in this town. This town. This old, bold, cold town. This big town. This pig town. “Every house a story…This gets up under your skin town…Fill you with wonder town…This quare, rare, my ho-o-ome is there town. Full of life town. Extract from Pigtown by local playwright, Mike Finn. Editor: Rachael Finucane Editorial Assistant: Adam Leahy Contributing writers: Rachael Finucane, Bríana Walsh and Adam Leahy. Photography: Lorcan O’Connell, Dave Gaynor, Limerick Marketing, Rachael Finucane, Fáilte Ireland, Tourism Ireland and others (see individual photos for details). Copyright retained by photographers/organisations. 2 | The Best Of Ireland Series Limerick Guide Contents THE BEST OF IRELAND Series Contents 4. Introducing Limerick 35. Get Active in Limerick 93. Further Afield 6. History & Heritage 48. Family Fun 96. Accommodation 15. Arts, Culture & 57. Shopping Heaven 98. Useful Information/ Education Services 69. Food & Drink 31. Festivals & Events 100. Maps A Tourism and Marketing Initiative from Southern Marketing Design Media € For enquiries about inclusion in updated editions of this guide, please contact 061 310286 / [email protected] RRP: 3.00 No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the publishers. © Southern Marketing Design Media 2016. Every effort has been made in the production of this magazine to ensure accuracy at the time of publication. The editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions, or for any alterations made after publication. Cover image: St. -

Key Audience Issues for Public Service Broadcaster, RTE Radio 1 (1995-2012)

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2013 Tuning In: Key Audience Issues for Public Service Broadcaster, RTE Radio 1 (1995-2012) Patrick Hannon Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Recommended Citation Hannon, P.: (2016). Tuning In: Key Audience Issues for Public Service Broadcaster, RTE Radio 1 (1995-2012). Masters dissertation. Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D7MW48 This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License To The Dublin Institute of Technology March 2012. Tuning in: Key audience issues for public service broadcaster, RTE Radio 1 (1995 -2012). By Patrick Hannon B.Sc. (Hons) Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. (Master of Philosophy) Supervisor: Dr. Brian O’ Neill School of Media, College of Arts and Tourism Dublin Institute of Technology January 2013 Abstract This thesis explores listener loyalty to public radio in Ireland where radio listenership is one of the highest in Europe. Critical to this study is exploring the notion and understanding – from the listeners’ perspective – of Public Service Broadcasting (PSB), in particular, the complexities of the concept as it is understood and operated by RTE Radio 1. A qualitative inquiry with twenty-three participants representing the audience and RTE management was carried out. -

BBC Statements of Programme Policy 2010/2011 2

BBC Statements of Programme Policy 2010/2011 These Statements cover the year from April 2010 to March 2011 Contents Director-General’s statement....................................................................... 3 Television ...................................................................................................... 4 BBC One ....................................................................................................................................... 4 BBC One Scotland Annex ............................................................................................................. 9 BBC One Wales Annex ............................................................................................................... 11 BBC One Northern Ireland Annex ............................................................................................... 13 BBC Two ..................................................................................................................................... 15 BBC Two Scotland Annex ........................................................................................................... 19 BBC Two Wales Annex ............................................................................................................... 21 BBC Two Northern Ireland Annex ............................................................................................... 23 BBC Three.................................................................................................................................. -

Classic Radio 1 Schedules (1967-2004)

Frequency Finder UK (www.frequencyfinder.org.uk) Classic Radio 1 Schedules (1967-2004) October 1967 In the early years, Radio 1 was very different. It was originally conceived as a general popular music network, broadcasting easy listening, jazz, folk and country as well as pop and rock music. The intention was that it would opt out of the Light Programme with music when the Light was carrying a speech programme. This was largely the pattern in the first few years, with a lot of sharing between Radios 1 and 2, though the two stations did carry separate music programmes at breakfast and late afternoon. The daytime schedules didn't fully separate until the 1970s. Another feature of the early schedule is that many programmes featured different presenters on different days or in different weeks. A lot of the presenters floated between several shows. Saturday Monday to Friday 05:30 As Radio 2 05:30 As Radio 2 07:00 Tony Blackburn 07:00 Tony Blackburn 08:30 Junior Choice with Leslie Crowther (also on R2) 08:30 Family Choice with a guest presenter (also on R2) 10:00 Saturday Club with Keith Skues 10:00 Jimmy Young (also on R2 until 11:00) 12:00 Emperor Rosko 12:00 Midday Spin with Simon Dee (Mon), Duncan 13:00 Jack Jackson (also on R2) Johnson (Tue), Kenny Everett (Wed), David Rider 14:00 Chris Denning (also on R2) (Thur) and Stuart Henry (Fri) (also on R2) 15:00 Pete Murray (also on R2) 13:00 (Mon) Dave Cash - Live Music 16:00 Pete Brady (also on R2) 13:00 (Tue) Keith Fordyce - Live Music 17:30 Country Meets Folk with Wally Whyton (also on 13:00 (Wed) Bob Miller and The Millermen with R2) Parade of the Pops - Live orchestral pop 18:30 Scene and Heard - magazine with Johnny Moran 13:00 (Thur) Pop North with the Northern Dance 19:30 As Radio 2 Orchestra 22:00 Pete Murray (easy listening, also on R2) 13:00 (Fri) The Joe Loss Show - Live orchestral pop 00:00-02:00 Night Ride with Sean Kelly (easy listening, 14:00 Pete Brady (also on R2 15:00-16:15) also on R2) 16:30 What's New 17:30 David Symonds Sunday 19:30 As Radio 2 except..