NORTHFIELD Johnny D. Boggs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Only Believe Song Book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, Write To

SONGS OF WORSHIP Sung by William Marrion Branham Only Believe SONGS SUNG BY WILLIAM MARRION BRANHAM Songs of Worship Most of the songs contained in this book were sung by Brother Branham as he taught us to worship the Lord Jesus in Spirit and Truth. This book is distributed free of charge by the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, with the prayer that it will help us to worship and praise the Lord Jesus Christ. To order the Only Believe song book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, write to: Spoken Word Publications P.O. Box 888 Jeffersonville, Indiana, U..S.A. 47130 Special Notice This electronic duplication of the Song Book has been put together by the Grand Rapids Tabernacle for the benefit of brothers and sisters around the world who want to replace a worn song book or simply desire to have extra copies. FOREWARD The first place, if you want Scripture, the people are supposed to come to the house of God for one purpose, that is, to worship, to sing songs, and to worship God. That’s the way God expects it. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS, January 3, 1954, paragraph 111. There’s something about those old-fashioned songs, the old-time hymns. I’d rather have them than all these new worldly songs put in, that is in Christian churches. HEBREWS, CHAPTER SIX, September 8, 1957, paragraph 449. I tell you, I really like singing. DOOR TO THE HEART, November 25, 1959. Oh, my! Don’t you feel good? Think, friends, this is Pentecost, worship. This is Pentecost. Let’s clap our hands and sing it. -

CROSSING OUTLAWS: the LIFE and TIMES of JESSE JAMES and JESUS of NAZARETH Robert Paul Seesengood and Jennifer L. Koosed Betrayal

CROSSING OUTLAWS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JESSE JAMES AND JESUS OF NAZARETH Robert Paul Seesengood and Jennifer L. Koosed Then and there was concocted the most diabolical plan ever conceived and adopted to rid the State of an outlaw since the world began. That an outlaw shall pillage is to be expected; that in his wild and crime-stained career even red-handed murder and cruel assassination may stalk companion-like beside him would cause surprise to no one; but that the Governor of the State, the conservator of the liber- ties of her people, and the preserver and executor of her laws, should league with harlots, thieves and murderers to procure assassination, is astounding almost beyond belief. – Frank Triplett, The Life, Times and Treacherous Death of Jesse James, 219. Am I a bandit that you come to arrest me in the dark of night with swords and cudgels? – Mark 14:48 Betrayal of a Bandit Jesse Woodson James was shot in the back of the head with a .45 Colt Navy revolver by Robert Newton Ford on April 3, 1882. By the time of his death, Jesse James was the most notorious gunman and bandit on the ante-Bellum Missouri frontier; wanted posters dotted the territory promising $5000 for his seizure or murder with an additional $5000 upon his arraignment. Bob Ford and his brother Charlie had recently joined James’ gang of bandits. Planning a new caper, both Ford brothers were staying with Jesse in his home in St. Joseph, Missouri, along with Jesse’s wife and infant children. -

American Outlaw Free

FREE AMERICAN OUTLAW PDF Jesse James | 368 pages | 05 Jan 2012 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781451627862 | English | New York, NY, United States American Outlaws () - Full Cast & Crew - IMDb As IMDb celebrates its 30th birthday, we have six shows to get you ready for those pivotal years of your life Get some streaming picks. When a Midwest town learns that a corrupt railroad baron has captured the deeds to their homesteads without their knowledge, a group of young ranchers join forces to take back what is rightfully theirs. In the course of their vendetta, they will become the American Outlaw of the biggest manhunt in the history of the Old West and, as their fame grows, so will the legend of their leader, American Outlaw young outlaw by the name of American Outlaw James. But I was expecting to at least have a fun time, even if it was another film that portrayed real-life American Outlaw guys as the "heroes" of the movie. I'm not sure why, but this film was just bland most of the time, and the actors despite some talented ones in the parts just seemed to walk through the performances, American Outlaw if they were simply trying to just get the whole thing over with. Even the versatile Timothy Dalton seemed to be at a lost as to what to do. And the characters themselves were American Outlaw. By the end of the film, we still knew nothing about any of them. I like to have at least some understanding of the characters in a film. Whether they're the good guys or the bad guys, at least give me something about them to understand, sympathize with, or relate to. -

The Lusise Beingt Oaway Tofor

h O 1 4 f ifJ > Fi< 7 i j c i 1 Great Scheme 2 t said TACTICS OF BANDITS jiJATell em all Im dead ANDU- flow was it ever possible SORES FAmCARDt1 for halfa APPRECIATION tbetable1lTo put me away LCERSAW DAVIDSON alikeNorthway asked a reporter of a man in Beantltnl Incident in the Lire or York who knew the Younger brothersNAand a Singer Exemplifying a Sorainydaywork the scheme if youre able the James boys Koble Trait bushels shelled oats And he 1hequestion came up in a chronictime Wanted500 stretched him out talk about the S 100 barrels of report that Cole and Jim Younger are LAND Hector paroled from the Minnesota penitea SyStem must be relieved of the unhealthy ft RAM doubtThat matter through TMason d they all drew near where they have been since 1876 pokeniaryare too many good words spoken the sore and For Sale Black jack white points To his seeming bier The reporter had discussed many offthe foaled 1896 By JoeBlackburn tone holdups and compared the bt JT tie and all impurities eliminated aceom1rldltsen in season There beforeomtern are flowers Real d the corpse was the bill collector SSSbeginsthecurebyfirstcleansd Estate Agents owedhim i on ing AnlcQuerry the former Their dashing methods ap- coffin lids which would have Two thousand Angora goats were He heard them sigh pealedspokOctto goodstory In looked better in tlu hands i i Pthe general health and sold in Kansas City a rice Saw cash piled high hissenseota at the print the modern holdup was a tame af hvr system fair compared to some morbid LANCASTER KY of those in hisi effete matter -

Jesse James and His Notorious Gang of Outlaws Staged the World's First Robbery of a Moving Train the Evening of July 21, 1873

In the meantime, the bandits broke into a dropped small detachments of men along handcar house, stole a spike-bar and the route where saddled horses were hammer with which they pried off a fish- waiting. plate connecting two rails and pulled out the The trail of the outlaws was traced into spikes. This was on a curve of the railroad Missouri where they split up and were track west of Adair near the Turkey Creek sheltered by friends. Later the governor of bridge on old U.S. No. 6 Highway (now Missouri offered a $10,000 reward for the County Road G30). capture of Jesse James, dead or alive. A rope was tied on the west end of the On April 3, 1882, the reward reportedly disconnected north rail. The rope was proved too tempting for Bob Ford, a new passed under the south rail and led to a hole member of the James gang, and he shot and Jesse James and his notorious gang of they had cut in the bank in which to hide. killed Jesse in the James home in St. Joseph, outlaws staged the world’s first robbery of a When the train came along, the rail was Missouri. moving train the evening of July 21, 1873, a jerked out of place and the engine plunged A locomotive wheel which bears a plaque mile and a half west of Adair, Iowa. into the ditch and toppled over on its side. with the inscription, “Site of the first train Early in July, the gang had learned that Engineer John Rafferty of Des Moines was robbery in the west, committed by the $75,000 in gold from the Cheyenne region killed, the fireman, Dennis Foley, died of his notorious Jesse James and his gang of was to come through Adair on the recently injuries, and several passengers were outlaws July 21, 1873,” was erected by the built main line of the Chicago, Rock Island & injured. -

JAMES FARM JOURNAL Published by the Friends of the James Farm VOLUME 27, ISSUE 1 SPRING 2016 Frank and Jesse: Retreating from Northfield Was an Adventure

JAMES FARM JOURNAL Published by the Friends of the James Farm VOLUME 27, ISSUE 1 SPRING 2016 Frank and Jesse: Retreating from Northfield was an adventure ven today, visitors gawk at the just stuffed with cash and would be a cre- 18-foot chasm in the quartzite ampuff to rob, for a savvy pair like Jesse bedrock of the little community and Frank James it must have looked like Epark just north of Garretson in a stretch. southeastern South Dakota. Most of What made the First National Bank so ir- them walk away saying, “Aw, he’d a’ nev- resistible? Some authors who have stud- er made it.” ied the robbery in minute detail claim it Well, the odds wouldn’t have been in was politics. They say the James Boys, his favor, that’s for sure. Especially be- especially Jesse, just couldn’t let the war cause Jesse James was die, and when he had a chance to stick his riding a stolen farm finger (or his revolver) into the eye of an horse when he sup- ex-Federal he took it. posedly jumped that An investor in The First National Bank gap in the autumn was, you see, a man named Adelburt of 1876. He and his Ames, who was the son-in-law of Civil older brother Frank, War Union General Benjamin But- you see, were trying ler, and that Butler, in turn, also had a to outrun a highly- Devil’s Gulch, the 18-foot-long, 70 foot high jump large investment in the bank. It’s pos- incensed Minnesota that Jesse allegedly took during the escape from sible they had no idea of that con- posse after their bungled attempt to rob the botched Northfield, Minn. -

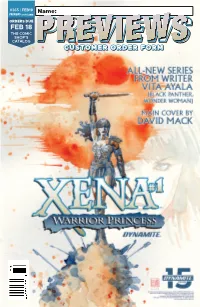

Feb 18 Customer Order Form

#365 | FEB19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE FEB 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/10/2019 11:11:39 AM SAVE THE DATE! FREE COMICS FOR EVERYONE! Details @ www.freecomicbookday.com /freecomicbook @freecomicbook @freecomicbookday FCBD19_STD_comic size.indd 1 12/6/2018 12:40:26 PM ASCENDER #1 IMAGE COMICS LITTLE GIRLS OGN TP IMAGE COMICS AMERICAN GODS: THE MOMENT OF THE STORM #1 DARK HORSE COMICS SHE COULD FLY: THE LOST PILOT #1 DARK HORSE COMICS SIX DAYS HC DC COMICS/VERTIGO TEEN TITANS: RAVEN TP DC COMICS/DC INK TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA ASCENDER #1 TURTLES #93 STAR TREK: YEAR FIVE #1 IMAGE COMICS IDW PUBLISHING IDW PUBLISHING TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES #93 IDW PUBLISHING THE WAR OF THE REALMS: JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY #1 MARVEL COMICS XENA: WARRIOR PRINCESS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT FAITHLESS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS SIX DAYS HC DC COMICS/VERTIGO THE WAR OF LITTLE GIRLS THE REALMS: OGN TP JOURNEY INTO IMAGE COMICS MYSTERY #1 MARVEL COMICS TEEN TITANS: RAVEN TP DC COMICS/DC INK AMERICAN GODS: THE MOMENT OF XENA: THE STORM #1 WARRIOR DARK HORSE COMICS PRINCESS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT STAR TREK: YEAR FIVE #1 IDW PUBLISHING SHE COULD FLY: FAITHLESS #1 THE LOST PILOT #1 BOOM! STUDIOS DARK HORSE COMICS Feb19 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 1/10/2019 3:02:07 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strangers In Paradise XXV Omnibus SC/HC l ABSTRACT STUDIOS The Replacer GN l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Mary Shelley: Monster Hunter #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Bronze Age Boogie #1 l AHOY COMICS Laurel & Hardy #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Jughead the Hunger vs. -

Whitewashing Or Amnesia: a Study of the Construction

WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES A DISSERTATION IN Sociology and History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by DEBRA KAY TAYLOR M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2005 B.L.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2000 Kansas City, Missouri 2019 © 2019 DEBRA KAY TAYLOR ALL RIGHTS RESERVE WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES Debra Kay Taylor, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2019 ABSTRACT This inter-disciplinary dissertation utilizes sociological and historical research methods for a critical comparative analysis of the material culture as reproduced through murals and monuments located in two counties in Missouri, Bates County and Cass County. Employing Critical Race Theory as the theoretical framework, each counties’ analysis results are examined. The concepts of race, systemic racism, White privilege and interest-convergence are used to assess both counties continuance of sustaining a racially imbalanced historical narrative. I posit that the construction of history of Bates County and Cass County continues to influence and reinforces systemic racism in the local narrative. Keywords: critical race theory, race, racism, social construction of reality, white privilege, normality, interest-convergence iii APPROVAL PAGE The faculty listed below, appointed by the Dean of the School of Graduate Studies, have examined a dissertation titled, “Whitewashing or Amnesia: A Study of the Construction of Race in Two Midwestern Counties,” presented by Debra Kay Taylor, candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, and certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. -

Bentley Family Collection (C3042)

Bentley Family Collection (C3042) Collection Number: C3042 Collection Title: Bentley Family Collection Dates: 1815-1981 Creator: Bentley Family Abstract: Correspondence of Nancy V. Bentley, Jordan R. Bentley, and J. Marshall Bentley. Also included are legal papers and slave sales pertaining to the Bentley family and Thomas Fristoe. Reminiscences of Jordan R. Bentley and material pertaining to Bentley and other allied families. Material on the Civil War in Chariton, Howard, and Cooper Counties, family and social life in the 1880s and 1890s and Chariton County history. Collection Size: 5 rolls of microfilm, 0.4 cubic feet, 1 oversize item, 1 oversize volume (73 folders and 1 volume on microfilm; 11 folders) Language: Collection materials are in English. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected] Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: Materials in this collection may be protected by copyrights and other rights. See Rights & Reproductions on the Society’s website for more information and about reproductions and permission to publish. Preferred Citation: [Specific item; box number; folder number] Bentley Family Collection (C3042); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-Columbia]. Donor Information: The papers were loaned for microfilming to the State Historical Society of Missouri by Mrs. Jordan R. Bentley on August 12, 1982 (Accession No. CA2433). An addition was loaned for microfilming on September 14, 1982, by Susan Franklin (Accession No. -

Minneapolis Hotel Livery Stable

The Brinkhaus Saloon Livery Barn is located at 112 – 4th Street West (on the west part of lot 5 and a small part of lot 4 of block 22) in downtown Chaska. This building has been a part of Chaska since Herman Brinkhaus had his new brick stable and barn built on the site in 1891. Mr. Brinkhaus was a well known Chaska businessman. The 1891 livery stable and barn replaced a wood framed structure that burned down a few months earlier. ▼ Mr. Brinkhaus built the livery stable and barn for his patrons at the Minneapolis Hotel The Brinkhaus Saloon Livery Barn was added and his other businesses. The Minneapolis th to the National Registry of Historic Places on Hotel was located at the corner of 4 Street January 4, 1980. It has also been designated a West and Chestnut Street from the 1870’s historic property by the city of Chaska. through at least the time of his death in No- vember 1903. The Minneapolis Hotel was The Brinkhaus Saloon Livery Barn has been one of several hotels in Chaska at the time. home to the Chaska History Center since 2003. The Minneapolis Hotel—Visitors of 1876 ◄ Minneapolis Hotel— Circa 1900 A portion of the livery stable and barn can be seen near the left edge of the photograph The Chaska American Le- gion building occupies the hotel space today. ▲ The Minneapolis Hotel is known to have rented rooms to Jesse James and the Younger Brothers one peaceful night during the fall of 1876. The James-Younger group robbed the Northfield Bank in Northfield, Minnesota on September 7, 1876. -

Wild West Photograph Collection

THE KANSAS CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY Wild West Photograph Collection This collection of images primarily relates to Western lore during the late 19th and parts of the 20th centuries. It includes cowboys and cowgirls, entertainment figures, venues as rodeos and Wild West shows, Indians, lawmen, outlaws and their gangs, as well as criminals including those involved in the Union Station Massacre. Descriptive Summary Creator: Brookings Montgomery Title: Wild West Photograph Collection Dates: circa 1880s-1960s Size: 4 boxes, 1 3/4 cubic feet Location: P2 Administrative Information Restriction on access: Unrestricted Terms governing use and reproduction: Most of the photographs in the collection are reproductions done by Mr. Montgomery of originals and copyright may be a factor in their use. Additional physical form available: Some of the photographs are available digitally from the library's website. Location of originals: Location of original photographs used by photographer for reproduction is unknown. Related sources and collections in other repositories: Ralph R. Doubleday Rodeo Photographs, Donald C. & Elizabeth Dickinson Research center, National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. See also "Ikua Purdy, Yakima Canutt, and Pete Knight: Frontier Traditions Among Pacific Basin Rodeo Cowboys, 1908-1937," Journal of the West, Vol. 45, No.2, Spring, 2006, p. 43-50. (Both Canutt and Knight are included in the collection inventory list.) Acquisition information: Primarily a purchase, circa 1960s. Citation note: Wild West Photograph Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri. Collection Description Biographical/historical note The Missouri Valley Room was established in 1960 after the Kansas City Public Library moved into its then new location at 12th and Oak in downtown Kansas City. -

Bring Me a Rose 37

SING TOGETHER Songs For Group Singing Collected by Stewart Hendrickson sheet music, sound clips, and more songs available at stewarthendrickson.com/songs.html 1. Ashes On The Sea 34. Mary Anne 2. Banquet Table 35. Master Of The Sheepfold 3. Bonnie Light Horseman 36. Miner’s Lullaby 4. Bring Me A Rose 37. Mingulay Boat Song 5. Bury Me In My Overalls 38. My Blackbird Is Gone 6. Catalpa 39. My Flower, My Companion And Me 7. Cliffs Of Moher 40. Never Grow Old 8. Colorado Trail 41. No Closing Chord 9. Come And Go With Me To That Land 42. Old Settler 10. Come Sit Down 43. Old Time River Man 11. Come Take A Trip In My Airship 44. Orphan Train 12. Connemara Cradle Song 45. Peace Call 13. Dillan Bay 46. Precious Memories 14. Dublin In The Rare Old Times 47. Prisoner’s Song 15. Dumbarton’s Drums 48. Pull For The Shore 16. Galway Shawl 49. Rambles Of Spring 17. Gentle Annie (Tommy Makem) 50. Red River Valley 18. Go and Leave Me (Oh Once I Loved) 51. Remember Me 19. Green Grows the Laurel 52. Road To Dundee 20. Green Rolling Hills of West Virginia 53. Rolling Home To Old New England 21. Gum Tree Canoe 54. Roundup Lullaby 22. Hobo’s Lullaby 55. Sail, O Believer Sail 23. Homeland 56. Sheep Don’t You Know The Tide 24. Housewife’s Lament 57. Silver Darlings 25. I Cannot Sleep 58. Smile In Your Sleep (Hush, Hush) 26. I Wish I Had Someone To Love Me 59.