Cultural Resources Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Southwestern Region, 2008

United States Department of Forest Insect and Agriculture Forest Disease Conditions in Service Southwestern the Southwestern Region Forestry and Forest Health Region, 2008 July 2009 PR-R3-16-5 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720- 2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Cover photo: Pandora moth caterpillar collected on the North Kaibab Ranger District, Kaibab National Forest. Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Southwestern Region, 2008 Southwestern Region Forestry and Forest Health Regional Office Salomon Ramirez, Director Allen White, Pesticide Specialist Forest Health Zones Offices Arizona Zone John Anhold, Zone Leader Mary Lou Fairweather, Pathologist Roberta Fitzgibbon, Entomologist Joel McMillin, Entomologist -

Santa Fe National Forest

Chapter 1: Introduction In Ecological and Biological Diversity of National Forests in Region 3 Bruce Vander Lee, Ruth Smith, and Joanna Bate The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY We summarized existing regional-scale biological and ecological assessment information from Arizona and New Mexico for use in the development of Forest Plans for the eleven National Forests in USDA Forest Service Region 3 (Region 3). Under the current Planning Rule, Forest Plans are to be strategic documents focusing on ecological, economic, and social sustainability. In addition, Region 3 has identified restoration of the functionality of fire-adapted systems as a central priority to address forest health issues. Assessments were selected for inclusion in this report based on (1) relevance to Forest Planning needs with emphasis on the need to address ecosystem diversity and ecological sustainability, (2) suitability to address restoration of Region 3’s major vegetation systems, and (3) suitability to address ecological conditions at regional scales. We identified five assessments that addressed the distribution and current condition of ecological and biological diversity within Region 3. We summarized each of these assessments to highlight important ecological resources that exist on National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico: • Extent and distribution of potential natural vegetation types in Arizona and New Mexico • Distribution and condition of low-elevation grasslands in Arizona • Distribution of stream reaches with native fish occurrences in Arizona • Species richness and conservation status attributes for all species on National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico • Identification of priority areas for biodiversity conservation from Ecoregional Assessments from Arizona and New Mexico Analyses of available assessments were completed across all management jurisdictions for Arizona and New Mexico, providing a regional context to illustrate the biological and ecological importance of National Forests in Region 3. -

Preservation News

Preservation News Vol. 2 No. 3 Fall 2015 NGPF STARTS RESTORAT ION EFFORTS FOR D&RGW T- 12 #168 The NGPF paid $10,000.00 for the move of D&RGW narrow gauge engine; T -12 #168, from its decades-long display site at a park across from the train station in Colorado Springs to insure restoration efforts could begin this winter. Raising money to restore an engine is far easier than raising money to move it from one place to another. Hence the NGPF felt it could make a difference by underwriting the move and helping the restoration project to start. The intent is to operate this T-12 on the C&TS. The history of this class of engine is explored in a related article on page 2, but it represents late 19th century technology for passenger power and remains an elegant example of the Golden Age of railroading. #168 was shopped at D&RGW’s shops at Burnham in Denver in 1938 and donated to the City of Colorado Springs where it has remained on display, cosmetically restored until it’s move this September for restoration. Indeed, it is possible that if the #168 is in as good shape as is hoped given its overhaul prior to being placed on display, a T class engine could be steaming in Colorado in 2016. The NGPF is helping to make this possible and the effort is off to a good start. And the engines Mal Ferrell called “these beautiful Rio Grande ten- wheelers” may be around for many years to come. -

USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021

1 USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021 Alabama Tuskegee, National Forests in Alabama, dates 6/6/2021--8/13/2021, Project Contact: Darrius Truss, [email protected] 404-550-5114 Double Springs, National Forests in Alabama, 6/6/2021--8/13/2021, Project Contact: Shane Hoskins, [email protected] 334-314- 4522 Alaska Juneau, Tongass National Forest / Admiralty Island National Monument, 6/14/2021--8/13/2021 Project Contact: Don MacDougall, [email protected] 907-789-6280 Arizona Douglas, Coronado National Forest, 6/13/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contacts: Doug Ruppel and Brian Stultz, [email protected] and [email protected] 520-388-8438 Prescott, Prescott National Forest, 6/13/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contact: Nina Hubbard, [email protected] 928- 232-0726 Phoenix, Tonto National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contact: Brooke Wheelock, [email protected] 602-225-5257 Arkansas Glenwood, Ouachita National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/30/2021, Project Contact: Bill Jackson, [email protected] 501-701-3570 Mena, Ouachita National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/30/2021, Project Contact: Bill Jackson, [email protected] 501- 701-3570 California Mount Shasta, Shasta Trinity National Forest, 6/28/2021--8/6/2021, Project Contact: Marcus Nova, [email protected] 530-926-9606 Etna, Klamath National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/31/2021, Project Contact: Jeffrey Novak, [email protected] 530-841- 4467 USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021 2 Colorado Grand Junction, Grand Mesa Uncomphagre and Gunnison National Forests, 6/7/2021--8/14/2021 Project Contact: Lacie Jurado, [email protected] 970-817-4053, 2 projects. -

Timeline for Long Term Monitoring

Timeline for long term monitoring Project (Grant #, and Treatment National Forest 5 Year 10 Year 15 Name) Start Date Management Unit Post Post Year Post 16-01 MRGCD Bosque 2003 Cibola NF 2008 2013 2018 06-02 San Juan Bosque 2003 Santa Fe NF 2008 2013 2018 03-01 La Jicarita 2005 Carson NF 2010 2015 2020 36-04 Turkey Springs 2005 Lincoln NF 2010 2015 2020 Ruidoso 27-04 Santa Fe FD WUI 2005 Santa Fe NF 2010 2015 2020 28-05 Ensenada 2006 Carson NF 2011 2016 2021 01-05 Bluewater 2006 Cibola NF 2011 2016 2021 21-04 Sierra SWCD Black 2006 Gila NF 2011 2016 2021 Range 39-05 SBS II -Cedar Creek 2006 Lincoln NF 2011 2016 2021 11-01 LTRR Monument 2006 Santa Fe NF 2011 2016 2021 Canyon 02-05 P&M Thunderbird 2007 Cibola NF 2012 2017 2022 05-07 Santa Ana Juniper II 2007 Cibola NF 2012 2017 2022 2007 Lincoln NF 13-07 Ruidoso Schools 2012 2017 2022 15 Project (Grant #, and Treatment National Forest 5 Year 10 Year Year Name) Start Date Management Unit Post Post Post 33-05 Taos Pueblo 2008 Carson NF 2013 2018 2023 16-07 FG III Santa 2008 Carson NF 2013 2018 2023 Cruz/Embudo 22-04 Gallinas -Tierra y 2008 Santa Fe NF 2013 2018 2023 Montes 22-07 Barela Timber 2008 Santa Fe NF 2013 2018 2023 25-07 Santa Clara Pueblo 2008 Santa Fe NF 2013 2018 2023 - Beaver 28-07 Santa Domingo 2008 Santa Fe NF 2013 2018 2023 Forest to Farm 29-07 SWPT Ocate State 2008 Santa Fe NF 2013 2018 2023 Lands Source: Derr, Tori, et. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABOUT US (i) FACTS ABOUT DVDs / POSTAGE RATES (ii) LOOKING AFTER YOUR DVDs (iii) Greg Scholl 1 Pentrex (Incl.Pentrex Movies) 9 ‘Big E’ 32 General 36 Electric 39 Interurban 40 Diesel 41 Steam 63 Modelling (Incl. Allen Keller) 78 Railway Productions 80 Valhalla Video Productions 83 Series 87 Steam Media 92 Channel 5 Productions 94 Video 125 97 United Kindgom ~ General 101 European 103 New Zealand 106 Merchandising Items (CDs / Atlases) 110 WORLD TRANSPORT DVD CATALOGUE 112 EXTRA BOARD (Payment Details / Producer Codes) 113 ABOUT US PAYMENT METHODS & SHIPPING CHARGES You can pay for your order via VISA or MASTER CARD, Cheque or Australian Money Order. Please make Cheques and Australian Money Orders payable to Train Pictures. International orders please pay by Credit Card only. By submitting this order you are agreeing to all the terms and conditions of trading with Train Pictures. Terms and conditions are available on the Train Pictures website or via post upon request. We will not take responsibility for any lost or damaged shipments using Standard or International P&H. We highly recommend Registered or Express Post services. If your in any doubt about calculating the P&H shipping charges please drop us a line via phone or send an email. We would love to hear from you. Standard P&H shipping via Australia Post is $3.30/1, $5.50/2, $6.60/3, $7.70/4 & $8.80 for 5-12 items. Registered P&H is available please add $2.50 to your standard P&H postal charge. -

Hclassification

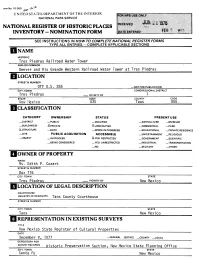

:ormNo. 10-300 . \0-lAr>' l^eM UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES •I INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS _________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS_____ | NAME HISTORIC Tres Piedras Railroad Water Tower______________________________ AND/OR COMMON Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad Water Tower at Tres Piedras LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Off U.S. 285 _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Tres Piedras _ VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mew Mexico 035 Taos 055, HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) -X.PRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK X-STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Ms. Edith P. Cozart STREET & NUMBER Box 776 CITY, TOWN STATE Tres Piedras — VICINITY OF New Mexico LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.-ETC. Ta0s County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Taos New Mexico REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE New Mexico State Register of Cultural Properties -FEDERAL JLSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Historic Preservation Section, New Mexico State Planning Office CITY. TOWN STATE Santa Fe New Mexico DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED -X.UNALTERED .^-ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD —RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE- AFAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The water tower in Tres Piedras that served the Denver and Rio Grande Western line is a standard 22 ft. -

New Mexico Day & Overnight Hikes Guide

CONTINENTAL DIVIDE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL DAY & OVERNIGHT HIKES NEW MEXICO PHOTO BY ERIC “DG”SHAW CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT NEW MEXICO Day & Overnight Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail The Land of Enchantment offers many wonderful ELEVATION: Many of these hikes are at elevations CDT experiences! From the rugged Rocky above 5,000 ft. Remember to bring plenty of water, Mountains to the desert grasslands of the sun protection, extra food, and know that a hike at Chihuahuan Desert, the CDT extends for 820 miles elevation may be more challenging than a similar in New Mexico, running through the present-day hike at sea level. and ancestral lands of numerous Native American tribes including the Chiricahua Apache, Pueblo, DRY CLIMATE: New Mexico gets an average of 14 Western Apache, Ute, Diné (Navajo), and Zuni inches of rain for the entire year. You will likely be tribes. New Mexico is home to pronghorn antelope, hiking in a very dry climate, so bring plenty of water roadrunners, gila monsters, javelinas, and turkey and stay hydrated. vultures, as well as ponderosa pines, cottonwoods, aspens, mesquite, prickly pears, and yuccas. NAVIGATION: Download the CDTC mapset at https://continentaldividetrail.org/maps. In this guide, you’ll find the state’s best day and The Guthook Guides phone application also provides overnight hikes on the CDT, organized from south a trail map and user-friendly, crowd-sourced to north. waypoint information for the entire CDT. Hike Types: OUT-AND-BACK POINT-TO-POINT LOOP Southern Terminus Begin at the Mexican border and experience the Big Hatchet Mountains Wilderness Study Area. -

Paths More Traveled: Predicting Future Recreation Pressures on America’S National Forests and Grasslands Donald B.K

United States Department of Agriculture Paths More Traveled: Predicting Future Recreation Pressures on America’s National Forests and Grasslands Donald B.K. English Pam Froemke A Forests on the Edge Report Kathleen Hawkos Forest Service FS-1034 June 2015 All photos © Thinkstock.com All photos Authors Key Words Learn More Donald B.K. English is a program Recreation, NVUM, national For further information manager for national visitor forests, population growth on this or other Forests on the Edge use monitoring; Forest Service, publications, please contact: Recreation, Heritage, and Volunteer Suggested Citation Resources Staff; Washington, DC. Anne Buckelew Pam Froemke is an information English, D.B.K.; Froemke, P.; U.S. Department of Agriculture technology specialist Hawkos, K.; 2014. Forest Service (spatial data analyst); Paths more traveled: Predicting Cooperative Forestry Staff Forest Service, Rocky Mountain future recreation pressures on 1400 Independence Avenue, SW Research Station; Fort Collins, CO. America’s national forests and Mailstop 1123 Kathleen Hawkos is a grasslands—a Forests on the Edge Washington, DC 20250–1123 cartographer/GIS specialist; report. FS-1034. Washington, DC: 202–401–4073 Forest Service, Southwestern U.S. Department of Agriculture [email protected] Regional Office, Albuquerque, NM. (USDA), Forest Service. 36 p. http://www.fs.fed.us/openspace/ Photos from front cover (top to bottom, left to right): © Thinkstock.com, © iStock.com, © Thinkstock.com, © iStock.com Paths More Traveled: Predicting Future Recreation Pressures on America’s National Forests and Grasslands A Forests on the Edge Report Learn More Abstract Populations near many national forests be expected to increase by 12 million new and grasslands are rising and are outpac- visits per year, from 83 million in 2010 to ing growth elsewhere in the United States. -

Northern Ohio Railway Museum Used Book Web Sale

NORTHERN OHIO RAILWAY MUSEUM USED BOOK 6/9/2021 1 of 20 WEB SALE No Title Author Bind Price Sale 343 100 Years of Capital Traction King Jr., Leroy O. H $40.00 $20.00 346026 Miles To Jersey City Komelski, Peter L. S $15.00 $7.50 3234 30 Years Later The Shore Line Carlson, N. S $10.00 $5.00 192436 Miles of Trouble Morse, V.L S $15.00 $7.50 192536 Miles of Trouble revised edition Morse, V.L. S $15.00 $7.50 1256 3-Axle Streetcars vol. 1 From Robinson to Rathgeber Elsner, Henry S $20.00 $10.00 1257 3-Axle Streetcars vol. 2 From Robinson to Rathgeber Elsner, Henry S $20.00 $10.00 1636 50 Best of B&O Book 3 50 favorite photos of B&O 2nd ed Kelly, J.C. S $20.00 $10.00 1637 50 Best of B&O Book 5 50 favorite photos of B&O Lorenz, Bob S $20.00 $10.00 1703 50 Best of PRR Book 2 50 favorite photos of PRR Roberts, Jr., E. L. S $20.00 $10.00 2 Across New York by Trolley QPR 4 Kramer, Frederick A. S $10.00 $5.00 2311Air Brake (New York Air Brake)1901, The H $10.00 $5.00 1204 Albion Branch - Northwestern Pacific RR Borden, S. S $10.00 $5.00 633 All Aboard - The Golden Age of American Travel Yenne, Bill, ed. H $20.00 $10.00 3145 All Aboard - The Story of Joshua Lionel Cowan Hollander, Ron S $10.00 $5.00 1608 American Narrow Gauge Railroads (Z) Hilton, George W. -

Rail History Walk

❹ ❺ State Archives Vámonos Old Water Tower Bldg., Chili Line 2020 ❸Original location of Loading Dock AT&SF Depot ❻ ❷ Santa Fe Depot / Romero St. Rail History Quiz “Wye” Rail History Walk & Model RR Route Map with Points of ❼Tomasita’s Historic Interpretation (Union (see reverse side) Station) ❶ Originally created in 2019 for Start/Finish: New Mexico Railroad ❽Gross-Kelly History Warehouse Celebration with Tracks at El Museo ❾ An easy walk in and around Turntable Santa Fe’s Downtown Railyard ⓮ Dual-Gauge Total Distance: 1.75 miles Track ❿Railyard Park Railway Gardens / NM Central RR ⓭ Santa Fe Main Line Rail (w/) Trail ⓬ ⓫ Acequia Trail Caboose Underpass / NM Central RR Guide to Stops on the Rail History Walk Start/Finish: New Mexico Railroad History Celebration at El Museo Cultural de Santa Fe, 555 ❶ Camino de la Familia, Santa Fe NM. Formerly Southwest Distributing, a beer warehouse. Romero St. “Wye” constructed circa 1882 to turn equipment without use of a turntable, with ❷ a spur that extended nearly to Agua Fria St. Site of original Santa Fe Depot, built by Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF) in 1880 ❸ to serve the new rail line from Lamy, functioned as a freight depot only after 1909. ❹ Site of old Water Tower and view of Santa Fe Builders Supply Company building, built c. 1887, a/k/a SanBusco Center, now NM School for the Arts. Rail History State Archives Building, soon to be Vladem Contemporary Art. Constructed as the Charles ❺ Ilfeld building, a wholesale grocery warehouse that opened in 1936. Loading dock served Denver & Rio Grande Western (D&RG) (a/k/a the “Chili Line”) and AT&SF railroads. -

Santa Fe Order Number: 10-493 Carson Order Number: 02-493 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of AGRICULTURE U.S. FOREST SERVICE CARSON

Santa Fe Order Number: 10-493 Carson Order Number: 02-493 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE U.S. FOREST SERVICE CARSON AND SANTA FE NATIONAL FORESTS Possessing Domestic Sheep or Goats within Wilderness areas PROHIBITIONS Pursuant to 16 U.S.C. § 551 and 36 C.F.R. § 261.50(a), the following acts are prohibited within the areas described in this Order (the “Restricted Areas”) and as depicted on the attached map, hereby incorporated into this Order as Exhibit A, within the Carson and Santa Fe National Forests, Taos, Rio Arriba, Mora, Colfax, Los Alamos, Sandoval, Santa Fe, San Miguel, and Mora Counties, New Mexico. 1. Possessing, storing, or transporting any domestic sheep or goat. 36 C.F.R. § 261.58(s). EXEMPTIONS Pursuant to 36 C.F.R. § 261.50(e), the following persons are exempt from this Order: 1. Persons with a written Forest Service authorization specifically exempting them from the effect of this Order. 2. Any Federal, State, or Local Officer, or member of an organized rescue or firefighting resource in the performance of an official duty. RESTRICTED AREAS The Restricted Areas are within the Congressionally designated boundaries of the Latir Peaks Wilderness Area, Columbine Hondo Wilderness Area, Pecos Wilderness Area, Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River Corridor, and Dome Wilderness, as depicted in Exhibit A of this Order. PURPOSE The purpose of this Order is to protect bighorn sheep from diseases transmitted by domestic sheep and goats. IMPLEMENTATION 1. This Order will be effective on May 28, 2021, at 0800 a.m., and shall remain in effect until December 31, 2025, or until rescinded, whichever occurs first.