" I Believe That We Will Win!": American Myth-Making and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Netherlands in Focus

Talent in Banking 2015 The Netherlands in Focus UK Financial Services Insight Report contents The Netherlands in Focus • Key findings • Macroeconomic and industry context • Survey findings 2 © 2015 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved. Key findings 3 © 2015 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved. Attracting talent is difficult for Dutch banks because they are not seen as exciting, and because of the role banks played in the financial crisis • Banking is less popular among business students in the Netherlands than in all but five other countries surveyed, and its popularity has fallen significantly since the financial crisis • Banks do not feature in the top five most popular employers of Dutch banking students; among banking-inclined students, the three largest Dutch banks are the most popular • The top career goals of Dutch banking-inclined students are ‘to be competitively or intellectually challenged’ and ‘to be a leader or manager of people’ • Dutch banking-inclined students are much less concerned with being ‘creative/innovative’ than their business school peers • Dutch banking-inclined students want ‘leadership opportunities’ and leaders who will support and inspire them, but do not expect to find these attributes in the banking sector • Investment banking-inclined students have salary expectations that are significantly higher than the business student average • Banks in the Netherlands are failing to attract female business students; this is particularly true of investment banks 4 © 2015 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved. Macroeconomic and industry context 5 © 2015 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved. Youth unemployment in the Netherlands has almost doubled since the financial crisis, but is relatively low compared to other EMEA countries Overall and youth unemployment, the Netherlands, 2008-2014 15% 10% 5% 0% 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Overall Youth (Aged 15-24) 6 Source: OECD © 2015 Deloitte LLP. -

The Labor Agreements Between UAW and the Big Three Automakers- Good Economics Or Bad Economics? John J

Journal of Business & Economics Research – January, 2009 Volume 7, Number 1 The Labor Agreements Between UAW And The Big Three Automakers- Good Economics Or Bad Economics? John J. Lucas, Purdue University Calumet, USA Jonathan M. Furdek, Purdue University Calumet, USA ABSTRACT On October 10, 2007, the UAW membership ratified a landmark, 456-page labor agreement with General Motors. Following pattern bargaining, the UAW also reached agreement with Chrysler LLC and then Ford Motor Company. This paper will examine the major provisions of these groundbreaking labor agreements, including the creation of the Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Association (VEBA), the establishment of a two tier wage structure for newly hired workers, the job security provisions, the new wage package for hourly workers, and the shift to defined contribution plans for new hires. The paper will also provide an economic analysis of these labor agreements to consider both if the “Big Three” automakers can remain competitive in the global market and what will be their impact on the UAW and its membership. Keywords: UAW, 2007 Negotiations, Labor Contracts BACKGROUND he 2007 labor negotiations among the Big Three automakers (General Motors, Chrysler LLC, and Ford Motor) and the United Autoworkers (UAW) proved to be historic, as well as controversial as they sought mutually to agree upon labor contracts that would “usher in a new era for the auto Tindustry.” Both parties realized the significance of attaining these groundbreaking labor agreements, in order for the American auto industry to survive and compete successfully in the global economy. For the UAW, with its declining membership of approximately 520,000, that once topped 1.5 million members, a commitment from the Big Three automakers for product investments to protect jobs and a new health care trust fund were major goals. -

Reflects True America

SPORTS SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 2016 Brazil thrash archrivals Argentina Brazil, Uruguay march towards 2018 MONTEVIDEO: Brazil thrashed arch-rivals Argentina to tight- en their grip on South America’s 2018 World Cup qualification campaign on Thursday as Uruguay maintained their push towards the finals with a hard-fought defeat of Ecuador. Barcelona superstar Neymar outshone club-mate Lionel Messi with his 50th international goal for Brazil in Belo Horizonte as the five-time World Cup winners romped to a 3-0 win in the Estadio Mineirao. It was a sweet return to the venue for Brazil, who were humiliated 7-1 at the same ground by Germany in the semi-finals of the 2014 World Cup. Neymar’s landmark strike was sandwiched by a spectacular effort from Liverpool’s Philippe Coutinho and a second-half finish from China-based midfielder Paulinho. The win was a remarkable fifth consecutive qualifying victory under the reign of new coach Tite, who took over following the sacking of Dunga in June after Brazil’s Copa America Centenario debacle, when they failed to advance from the group stage. Brazil now have 24 points from 11 games, one clear of second-placed Uruguay who have 23 points. The Brazilians are six points clear of third-placed Colombia and seven points clear of Ecuador and Chile, who are level on 17 points after 11 games. Argentina meanwhile are languish- ing outside the qualifying places in sixth with 16 points. The two-time world champions-who have taken just two points from their past four qualifiers-now face a crucial game at home to Colombia next Tuesday which they must win to avoid falling further off the pace. -

Ross Bernstein Motivational Speaker & Best-Selling Sports Author

SUSAN GUZZETTA PROFESSIONAL SPEAKERS FOR ALL OCCASIONS ROSS BERNSTEIN MOTIVATIONAL SPEAKER & BEST-SELLING SPORTS AUTHOR SPEAKER The best-selling author of nearly 50 sports books, Ross Bernstein is an award-winning peak performance business speaker who’s keynoted conferences on four continents for audiences as small as 10 and as large as 10,000. Ross and his books have been featured on thousands of television and radio programs over the years including CNN, ESPN, Bloomberg, Fox News, and “CBS This Morning,” as well as in the Wall Street Journal, New York Times and USA Today. He’s spent the better part of the past 20 years studying the DNA of championship teams and his program, “The Champion’s Code: Building Relationships Through Life Lessons of Integrity and Accountability from the Sports World to the Business World,” not only illustrates what it takes to become the best of the best, it also explores the fine line between cheating and gamesmanship in sports as it relates to values and integrity in the workplace. As a working member of the media in his home state of Minnesota, Ross has a unique behind the scenes access to all of the local sports franchises in the area, including the Vikings, Twins, Timberwolves, Wild and Gophers. As such, he spends lots of his time in dugouts, club houses, locker rooms, and press boxes — and it’s here where Ross has met and interviewed thousands of professional athletes over the years. Ross and his wife Sara have a 12 year old daughter and presently reside in Apple Valley, MN. -

Theory of the Beautiful Game: the Unification of European Football

Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 54, No. 3, July 2007 r 2007 The Author Journal compilation r 2007 Scottish Economic Society. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main St, Malden, MA, 02148, USA THEORY OF THE BEAUTIFUL GAME: THE UNIFICATION OF EUROPEAN FOOTBALL John Vroomann Abstract European football is in a spiral of intra-league and inter-league polarization of talent and wealth. The invariance proposition is revisited with adaptations for win- maximizing sportsman owners facing an uncertain Champions League prize. Sportsman and champion effects have driven European football clubs to the edge of insolvency and polarized competition throughout Europe. Revenue revolutions and financial crises of the Big Five leagues are examined and estimates of competitive balance are compared. The European Super League completes the open-market solution after Bosman. A 30-team Super League is proposed based on the National Football League. In football everything is complicated by the presence of the opposite team. FSartre I Introduction The beauty of the world’s game of football lies in the dynamic balance of symbiotic competition. Since the English Premier League (EPL) broke away from the Football League in 1992, the EPL has effectively lost its competitive balance. The rebellion of the EPL coincided with a deeper media revolution as digital and pay-per-view technologies were delivered by satellite platform into the commercial television vacuum created by public television monopolies throughout Europe. EPL broadcast revenues have exploded 40-fold from h22 million in 1992 to h862 million in 2005 (33% CAGR). -

St. Cloud State Huskies 2014-15 Schedule Quick Facts Date Opponent Time (CT) Sat., Oct

St. Cloud State HuSkieS 2014-15 Schedule Quick Facts Date Opponent Time (CT) Sat., Oct. 4 Trinity Western (Exh.) 7:00 p.m. Location (Pop.): ..................... St. Cloud, Minn. (66,297) Fri., Oct. 10 Colgate 7:37 p.m. Founded: ............................................................... 1869 Sat., Oct. 11 Colgate 7:07 p.m. Enrollment: ......................................................... 16,245 Fri., Oct. 24 at Union 6:00 p.m. Sat., Oct. 25 at Union 6:00 p.m. Nickname:..........................................................Huskies Fri., Oct. 31 Minnesota 7:37 p.m. Colors: ............................................. Cardinal and Black Sat., Nov. 1 at Minnesota 4:00 p.m. President: ....................................... Dr. Earl H. Potter III Fri., Nov. 7 Minnesota Duluth* 7:37 p.m. Director of Athletics:............................. Heather Weems Sat., Nov. 8 Minnesota Duluth* 7:07 p.m. Hockey Admin.:.................................... Heather Weems Fri., Nov. 14 at Western Michigan* 6:00 p.m. Faculty Athletic Rep.: ..............................Dr. Bill Hudson Sat., Nov. 15 at Western Michigan* 6:00 p.m. Athletic Dept. Phone #: ..........................(320) 308-3102 Fri., Nov. 21 North Dakota* 7:37 p.m. Sat., Nov. 22 North Dakota* 7:07 p.m. SEASON IN REVIEW Fri., Nov. 28 at Bemidji State 7:37 p.m. 2013-14 Overall Record: ................................... 22-11-5 Sat., Nov. 29 at Bemidji State 7:07 p.m. 2013-14 NCHC Record/Finish: ...................15-6-3-0/1st Fri., Dec. 12 at Omaha* 7:37 p.m. 2014 NCHC Tournament Record: ............................. 0-2 Sat., Dec. 13 at Omaha* 7:07 p.m. 2014 NCHC Tournament Finish: ................Quarterfinals Fri., Jan. 2 Quinnipiac 7:37 p.m. 2014 NCAA Tournament Finish: ............. Regional Final Sat., Jan. -

MLS Game Guide

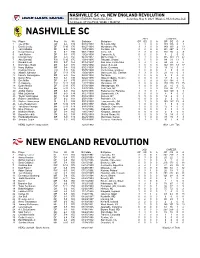

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Registration, Inspection, and Financial Responsibility Requirements

THE BIG THREE - REGISTRATION, INSPECTION, AND FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY REQUIREMENTS THE BIG THREE – REGISTRATION, INSPECTION, AND FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY REQUIREMENTS Registration Inspection Financial Responsibility Transportation Code §502.002—Motor vehicles must be Transportation Code §548.051—Those motor vehicles Transportation Code §601.051—Cannot operate a registered within 30 days after purchasing a vehicle or registered in this state must be inspected (list of vehicles motor vehicle unless financial responsibility is General Rule becoming a Texas resident. not required to be inspected found at Transportation established for that vehicle (motor vehicle defined Code §548.052). in §601.002(5)). Transportation Code §502.006(a)—Cannot be registered for Not required. Required if all-terrain vehicle is designed for use on operation on a public highway EXCEPT state, county, or a highway. “All-Terrain municipality may register all-terrain vehicle for operation Vehicles” on any public beach or highway to maintain public safety Not required if all-terrain vehicle is not designed and welfare. for use on a highway (see definition of motor vehicle in Transportation Code §601.002(5)). Transportation Code §504.501—Special registration Not required; must instead pass initial safety inspection Required. “Custom Vehicle” procedures for custom vehicles. at time of registration. Transportation Code §502.0075—Not required to be Not required. Not required—not a motor vehicle under “Electric Bicycles” registered. Transportation Code §541.201(11). “Electric Personal Transportation Code §502.2862—Not required to be Not required. Not required—not a motor vehicle under Assistive Mobility Device” registered. Transportation Code §601.002(5) or §541.201(11). Transportation Code §551.402—Cannot be registered for Not required; must display a slow-moving-vehicle No financial responsibility for golf carts operated “Golf Carts” operation on a public highway. -

DCDC Strategic Trends Programme: Future Operating

Strategic Trends Programme Future Operating Environment 2035 © Crown Copyright 08/15 Published by the Ministry of Defence UK The material in this publication is certified as an FSC mixed resourced product, fully recyclable and biodegradable. First Edition 9027 MOD FOE Cover B5 v4_0.indd 1-3 07/08/2015 09:17 Strategic Trends Programme Future Operating Environment 2035 First Edition 20150731-FOE_35_Final_v29-VH.indd 1 10/08/2015 13:28:02 ii Future Operating Environment 2035 20150731-FOE_35_Final_v29-VH.indd 2 10/08/2015 13:28:03 Conditions of release The Future Operating Environment 2035 comprises one element of the Strategic Trends Programme, and is positioned alongside Global Strategic Trends – Out to 2045 (Fifth Edition), to provide a comprehensive picture of the future. This has been derived through evidence-based research and analysis headed by the Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre, a department within the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MOD). This publication is the first edition of Future Operating Environment 2035 and is benchmarked at 30 November 2014. Any developments taking place after this date have not been considered. The findings and deductions contained in this publication do not represent the official policy of Her Majesty’s Government or that of UK MOD. It does, however, represent the view of the Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre. This information is Crown copyright. The intellectual property rights for this publication belong exclusively to the MOD. Unless you get the sponsor’s authorisation, you should not reproduce, store in a retrieval system or transmit its information in any form outside the MOD. -

~'7/P64~J Adviser Department of S Vie Languages and Literatures @ Copyright By

FREEDOM AND THE DON JUAN TRADITION IN SELECTED NARRATIVE POETIC WORKS AND THE STONE GUEST OF ALEXANDER PUSHKIN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By James Goodman Connell, Jr., B.S., M.A., M.A. The Ohio State University 1973 Approved by ,r-~ ~'7/P64~j Adviser Department of S vie Languages and Literatures @ Copyright by James Goodman Connell, Jr. 1973 To my wife~ Julia Twomey Connell, in loving appreciation ii VITA September 21, 1939 Born - Adel, Georgia 1961 .•..••. B.S., United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland 1961-1965 Commissioned service, U.S. Navy 1965-1967 NDEA Title IV Fellow in Comparative Literature, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 1967 ••••.•. M.A. (Comparative Literature), The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 1967-1970 NDFL Title VI Fellow in Russian, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1969 •.•••.• M.A. (Slavic Languages and Literatures), The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1970 .•...•. Assistant Tour Leader, The Ohio State University Russian Language Study Tour to the Soviet Union 1970-1971 Teaching Associate, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1971-1973 Assistant Professor of Modern Foreign Languages, Valdosta State College, Valdosta, Georgia FIELDS OF STUDY Major field: Russian Literature Studies in Old Russian Literature. Professor Mateja Matejic Studies in Eighteenth Century Russian Literature. Professor Frank R. Silbajoris Studies in Nineteenth Century Russian Literature. Professors Frank R. Silbajoris and Jerzy R. Krzyzanowski Studies in Twentieth Century Russian Literature and Soviet Literature. Professor Hongor Oulanoff Minor field: Polish Literature Studies in Polish Language and Literature. -

Fair Play 1964-2005 INGLESE

Fair Play Trophies et Diplomas awarded by IFPC from 1964 to 2005 Winners Publication edited in agreement with the International Committee for Fair Play Panathlon International Villa Porticciolo – Via Maggio, 6 16035 Rapallo - Italie www.panathlon.net e-mail: [email protected] project and cultural coordination International Committee for Fair Play Panathlon International works coordinators Jean Durry Siropietro Quaroni coordination assistants Nicoletta Bena Emanuela Chiappe page layout and printing: Azienda Grafica Busco - Rapallo 2 Contents Jeno Kamuti 5 The "Fair Play", its sense and its winners Enrico Prandi 8 “Angel or Demon? The choise of Fair Play” Definition and History 11 of the International Committee for Fair Play Antonio Spallino 25 Panathlon International and the promotion of Fair Play Fair Play World Trophies Trophies and Diplomas 33 awarded by International Committee for Fair play from the origin Letters of congratulations 141 Nations legend 150 Disciplines section 155 Alphabethical index 168 3 Jeno Kamuti President of the International Fair Play Committee The “Fair Play”, its sense and its winners Nowadays, at the beginning of the XXIst century, sport has finally earned a worthy place in the hier - archy of society. It has become common wisdom that sport is not only an activity assuring physical well-being, it is not only a phenomenon carrying and reinforcing human values while being part of general culture, but that it is also a tool in the process of education, teaching and growing up to be an upright individ - ual. Up until now, we have mostly contented our - selves with saying that sport is a mirror of human activities in society. -

2020 MLS Standings and Leaders Includes Games of Sunday, November 08, 2020 OVERALL HOME ROAD

2020 MLS Standings and Leaders Includes games of Sunday, November 08, 2020 OVERALL HOME ROAD East GP W L T PTS GF GA GD W L T GF GA W L T GF GA Philadelphia Union 23 14 4 5 47 44 20 24 9 0 0 24 4 3 4 4 16 14 Toronto FC 23 13 5 5 44 33 26 7 7 2 1 14 6 5 3 2 13 15 Columbus Crew SC 23 12 6 5 41 36 21 15 9 1 0 20 6 0 5 5 9 15 Orlando City SC 23 11 4 8 41 40 25 15 6 1 3 22 11 3 3 4 12 11 New York City FC 23 12 8 3 39 37 25 12 7 2 0 23 9 4 4 3 12 12 New York Red Bulls 23 9 9 5 32 29 31 -2 5 4 1 13 12 3 3 4 15 15 Nashville SC 23 8 7 8 32 24 22 2 4 2 5 14 9 4 5 3 10 13 New England Revolution 23 8 7 8 32 26 25 1 2 3 5 10 11 5 4 1 14 13 Montreal Impact 23 8 13 2 26 33 43 -10 3 6 1 12 16 4 5 1 17 22 Inter Miami CF 23 7 13 3 24 25 35 -10 5 2 2 14 13 2 8 1 9 17 Chicago Fire 23 5 10 8 23 33 39 -6 4 2 3 21 13 0 6 5 10 21 Atlanta United 23 6 13 4 22 23 30 -7 4 4 2 10 9 2 6 2 13 18 D.C.