Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-19 Chronological Calendar

2018-19 (119TH SEASON) Chronological Calendar (as of January 31, 2018) OPENING NIGHT September 13 at 7:00 PM–Thursday evening—Verizon Hall at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor André Watts Piano Rossini Overture to William Tell Strauss Don Juan Join us as we kick off The Philadelphia Orchestra’s 119th season in high style. The Opening Night Concert and Gala for the 2018-19 season promises to be a highlight of the cultural year. Yannick, internationally renowned pianist André Watts (who made his debut with the Orchestra in 1957, at the age of 10), and the Fabulous Philadelphians are planning a special celebratory program that features musical masterworks and audience favorites, including Rossini’s famous Overture to William Tell and Strauss’s Don Juan. Opening Night Co-Chairs Alison Avery Lerman and Lexa Edsall, Volunteer Association President Lisa Yakulis, Board Chairman Richard Worley, and the Opening Night Gala committee look forward to welcoming you to this special evening, featuring great music, high couture and black tie, and delicious food and champagne with Philadelphia’s cultural leaders and arts patrons. Contact Dorothy Byrne in the Volunteer Relations office at 215.893.3124 or via e-mail at [email protected] to make sure you are on the invitation list. Concert-only tickets for the evening are also available—simply add them to your subscription. January 31, 2018—All programs and artists subject to change. PAGE 2 The Philadelphia Orchestra 2018-19 Chronological -

Music K-8 Marketplace 2021 Spring Update Catalog

A Brand New Resource For Your Music Classroom! GAMES & GROOVES FOR BUCKET BAND, RHYTHM STICKS, AND LOTS OF JOYOUS INSTRUMENTS by John Riggio and Paul Jennings Over the last few years, bucket bands have grown greatly in popularity. Percussion is an ideal way to teach rhythmic concepts and this low-cost percussion ensemble is a great way to feel the joy of group performance without breaking your budget. This unique new product by John Riggio and Paul Jennings is designed for players just beyond beginners, though some or all players can easily adapt the included parts. Unlike some bucket band music, this is written with just one bucket part, intended to be performed on a small to medium-size bucket. If your ensemble has large/bass buckets, they can either play the written part or devise a more bass-like part to add. Every selection features rhythm sticks, though the tracks are designed to work with just buckets, or any combination of the parts provided. These change from tune to tune and include Boomwhackers®, ukulele, cowbell, shaker, guiro, and more. There are two basic types of tunes here, games and game-like tunes, and grooves. The games each stand on their own, and the grooves are short, repetitive, and fun to play, with many repeats. Some songs have multiple tempos to ease learning. And, as you may have learned with other music from Plank Road Publishing and MUSIC K-8, we encourage and permit you to adapt all music to best serve your needs. This unique collection includes: • Grizzly Bear Groove • Buckets Are Forever (A Secret Agent Groove) • Grape Jelly Groove • Divide & Echo • Build-A-Beat • Rhythm Roundabout ...and more! These tracks were produced by John Riggio, who brings you many of Plank Road’s most popular works. -

July 26, 2013 Bugs Bunny and the NSO Come to Wolf Trap

July 26, 2013 Bugs Bunny and the NSO come to Wolf Trap By Roger Catlin For a generation of Americans, the earliest love of classical music came not through shared family symphony experiences or early childhood music appreciation classes, but through mayhem-laced TV cartoons, often involving a bunny in drag. Walt Disney may have taken the high road to classical music interpretation through some early Silly Symphony cartoons and “Fantasia” (which in its first run was a flop). But it was Warner Bros. and particularly the animators behind Bugs Bunny who may have been the most successful in drumming key classical passages into the heads of impressionable audiences when the studio’s theatrical cartoons of the 1940s and ’50s were incessantly replayed on TV in the ’60s. Warner Bros. - Still image from the 1950's Merrie Melodies short, “What's Opera, Doc?” Even today, the most serious gray-haired music lover, sitting in the world’s most august concert halls, may be listening to the timeless refrains of Rossini or Wagner only to have the phrase “Kill the Wabbit!” come to mind. Conductor George Daugherty has embraced this meld of classical knowledge and pop-culture conditioning and celebrates it in his “Bugs Bunny at the Symphony.” Its first tour, in 1990, was such a success that it spawned, as most successes in Hollywood do, a sequel. “Bugs Bunny at the Symphony II” comes to Wolf Trap on Thursday and Friday, with Daugherty conducting the National Symphony Orchestra. In its honor, we pause to hail the greatest uses of classical music by Warner Bros. -

Kill the Wabbit!« – Richard Wagner Im Hollywood-Cartoon Carsten Gerwin (Bielefeld)

»Kill the Wabbit!« – Richard Wagner im Hollywood-Cartoon Carsten Gerwin (Bielefeld) I. Einleitung Die Musik Richard Wagners ist im Hollywood-Cartoon ein nicht gerade selten anzutreffender Gast. Besonders Chuck Jones´ berühmter Warner- Bros.-Cartoon WHAT'S OPERA, DOC? aus dem Jahr 1957, in dem Wagnersche Musik aus fünf1 verschiedenen Bühnenwerken Verwendung findet, ist hier hervorzuheben. Viel ist bereits über diesen Cartoon, v. a. in Beiträgen der US-amerikanischen Forschung, geschrieben worden. Die Begründung der zitierten Musikausschnitte fällt aber zumeist einseitig und recht vage aus. Die Popularität der Beispiele sowie deren wechselvolle Rezeptionsgeschichte sind weder die einzigen, noch die schlüssigsten Kriterien für die Musikauswahl, zumal einige der zitierten Melodien und Motive in WHAT'S OPERA, DOC? Nicht-Wagnerianern unbekannt sein dürften. Dies gilt entsprechend auch für andere Cartoons. Mein methodischer Ansatz ist es, den ursprünglichen Kontext der Musikbeispiele in die Deutung der Cartoonszenen einzubeziehen. Natürlich ist hierbei die Gefahr der Überinterpretation besonders groß, weshalb es wichtig ist, klare Deutungsgrenzen zu ziehen. Dazu werden im Folgenden die Arbeitsweisen des zuständigen Komponisten Milt Franklyn, sowie seines musikalischen Mentors und Kollegen Carl Stalling näher beleuchtet. 1 Die genaue Anzahl der verwendeten Werke Wagners in diesem Cartoon richtet sich danach, ob die vier großen Bestandteile der Ring-Tetralogie, die gleiche Leitmotive enthalten, einzeln gezählt werden. Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 11, 2014 // 78 II. Zur Rolle der Musik in WHAT'S OPERA, DOC? Wer zum ersten Mal bewusst Cartoonmusiken von Carl Stalling oder Milt Franklyn hört, mag über die Vielzahl musikalischer Zitate verwundert sein. Den Warner-Studios gehörte in den 1930er Jahren ein eigener Musikverlag und so konnten sie über die Verwendung der dort publizierten Musik frei verfügen. -

For Immediate Release New Jersey Symphony Orchestra Announces Bugs Bunny at the Symphony Ii

National & NYC Press Contact: Dan Dutcher Public Relations Dan Dutcher | 917.566.8413 | [email protected] New Jersey Press Contact: Victoria McCabe, NJSO Communications and External Affairs 973.735.1715 | [email protected] www.njsymphony.org/pressroom FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NEW JERSEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ANNOUNCES BUGS BUNNY AT THE SYMPHONY II CLASSIC LOONEY TUNES CARTOONS TO SCREEN ABOVE LIVE ORCHESTRAL PERFORMANCE ADULT TICKETS START AT $20; CHILDREN’S TICKETS ARE HALF PRICE Sat, Jan 3, at NJPAC in Newark Sun, Jan 4, at State Theatre in New Brunswick NEWARK, NJ (September 8, 2014)—The New Jersey Symphony Orchestra presents BUGS BUNNY AT THE SYMPHONY II— a spectacular fusion of classical music and classic animation that celebrates the world’s most famous and beloved cartoons and their equally famous music—on January 3–4, 2015, at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC) in Newark and State Theatre in New Brunswick. Conducted by Emmy Award winner George Daugherty, and created and produced by Daugherty and Emmy Award-winning producer David Ka Lik Wong, Bugs Bunny at the Symphony II is a celebration of the world’s favorite Warner Bros. Looney Tunes characters on-screen with live full symphony orchestra accompaniment. These NJSO concerts are the first performances of the production’s landmark 25th-anniversary season. These milestone performances take place on Saturday, January 3, at 3 pm at NJPAC and Sunday, January 4, at 3 pm at the State Theatre. Adult tickets start at $20; tickets for children age 15 and younger are half price. Full concert information is available at www.njsymphony.org/events/detail/warner-bros-presents-bugs-bunny-at-the-symphony-2. -

PRESS RELEASE for Immediate Release

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release Erie Philharmonic brings Warner Brother’s cartoons back to the Warner Theatre Erie, PA | February 7, 2018 This weekend the Erie Philharmonic brings Bugs Bunny at the Symphony II to the Warner Theatre stage. The theater, originally built by the Warner Brothers—Jack, Harry, and their siblings—is one of the last original Warner Theatres left standing in America. The concert will take audiences back decades ago to when the Warner was a movie palace. Audiences will have the exclusive opportunity to see 16 classic LOONY TUNES projected on the big screen while the Erie Philharmonic performs the soundtracks live. There will be a performance on Saturday February 10 at 8:00pm and a matinee on Sunday February 11 at 2:30pm. George Daugherty will conduct the orchestra in classics such as What’s Opera, Doc?, The Rabbit of Seville, Baton Bunny, Rhapsody Rabbit, Zoom and Bored, and many more. Creators George Daugherty and David Ka Lik Wong bring Bugs Bunny, Elmer Fudd, Daffy Duck, Sylvester, Road Runner, Wile E. Coyote, and the rest of the gang to Erie for two already-packed performances. Saturday’s concert is SOLD OUT, but there are still limited tickets available for the Sunday matinee. Tickets for both concerts are expected to be released throughout the week as well as returned at the door the night of the performance so guests are encouraged to check the website or call the box office to see if seats are available. On Saturday night, seats will be sold to patrons waiting in the box office line on a first-come, first- served basis. -

[email protected] BUGS BUNNY

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PROGRAM UPDATE March 9, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] BUGS BUNNY AT THE SYMPHONY Presented by the New York Philharmonic and Warner Bros. NEW DATE ADDED: May 14, 2015, at 7:30 p.m. Concert To Feature Tribute to Looney Tunes Director Chuck Jones WHOOPI GOLDBERG To Appear as Special Guest May 15–16, 2015 GEORGE DAUGHERTY To Conduct New York Philharmonic in Original Animation Scores as Classic Looney Tunes Are Screened Celebrating 25th Anniversary of Looney Tunes on the Live Concert Stage Due to popular demand, the New York Philharmonic and Warner Bros. will present an additional performance of Bugs Bunny at the Symphony, a program celebrating classic Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons with the New York Philharmonic playing the music live while the animation is screened. The newly added concert, on May 14, 2015, at 7:30 p.m., will feature a tribute to Looney Tunes director Chuck Jones, including a montage of his most iconic cartoons and film clips of the famed animator speaking about his history creating Looney Tunes cartoons. During the concert, the Chuck Jones family and the Chuck Jones Center for Creativity will present to the New York Philharmonic a full-size oil replica of the painting Bugs at the Piano, rendered by Mr. Jones before his passing in 2002. As previously announced, Academy Award winner and New York Philharmonic Board Member Whoopi Goldberg will appear as a special guest on the May 15 and 16 concerts. All four concerts will be conducted by Emmy Award winner George Daugherty in his Philharmonic debut. -

MAGAZINE Vol

July 1996 MAGAZINE Vol. 1, No. 4 ANIMATION WORLD MAGAZINE July 1996 The Great Adventures of Izzy — An Olympic Hero for Kids by Frankie Kowalski 35 A look at the making of the first TV special based on an Olympic games mascot. “So,What Was It Like?” The Other Side Of Animation's Golden Age” by Tom Sito 37 Tom Sito attempts to puncture some of the illusions about what it was like to work in Hollywood's Golden Age of Animation of the 1930s and 40s, showing it may not have been as wild and wacky as some may have thought. When The Bunny Speaks, I Listen by Howard Beckerman 42 Animator Howard Beckerman explains why, "Cartoon characters are the only personalities you can trust." No Matter What,Garfield Speaks Your Language by Pam Schechter 46 Attorney Pam Schechter explores the ways cartoon characters are exploited and the type of money that's involved. Festival Reviews and Perspectives: Cardiff 96 by Bob Swain 49 Zagreb 96 by Maureen Furniss 53 Film Reviews: The Hunchback of Notre Dame by William Moritz 57 Desert Island Series... The Olympiad of Animation compiled by Frankie Kowalski 61 Picks from Olympiad animators Melinda Littlejohn, Raul Garcia, July 1996 George Schwizgebel and Jonathan Amitay. News Tom Sito on Virgil Ross + News 63 Preview of Coming Attractions 67 © Animation World Network 1996. All rights reserved. No part of the periodical may be reproduced without the consent of Animation World Network. Cover: The Spirit of the Olympics by Jonathan Amitay 3 ANIMATION WORLD MAGAZINE July 1996 The Great Adventures of Izzy — An Film Roman’s version of Izzy. -

FINAL VERSION Bugs Bunny at the Symphony 25Th Anniversary Press

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 5, 2015 BUGS BUNNY AT THE SYMPHONY CELEBRATES ITS 25th ANNIVERSARY 20-City Tour and Special Performances with New York Philharmonic at Lincoln Center and with Los Angeles Philharmonic at Hollywood Bowl Warner Bros. Consumer Products announced today that Bugs Bunny at the Symphony, the record- setting orchestra-and-film concert that invented a whole new genre of symphony orchestra concerts, is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year with an exuberant 20-city U.S. and Canada tour that includes special gala celebrations with the New York Philharmonic, already sold-out in four performances at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl. “We’re honored to be celebrating 25 years of Bugs Bunny at the Symphony as it continues to entertain generations of fans at landmark venues around the world,” said Karen McTier, Executive Vice President, Warner Bros. Consumer Products. “Music has always been at the heart of the beloved Looney Tunes and we are thrilled to continue to bring music, laughter and artistic inspiration to worldwide audiences in this celebratory tour.” In the summer of 1990, Primetime Emmy Award winners George Daugherty and David Ka Lik Wong created and premiered Bugs Bunny On Broadway to a sold-out house at the San Diego Civic Theatre with the San Diego Symphony conducted by Daugherty, followed by the critically-acclaimed extended run at The Gershwin Theatre on Broadway, in New York. The iconic animated shorts were created by some of the most creative minds in film—from the visual brilliance of such directors as Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, Bob Clampett, Tex Avery, and Robert McKimson. -

El CINECLUB UNIVERSITARIO Se Crea En 1949 Con El Nombre De “Cineclub De Granada”

La noticia de la primera sesión del Cineclub de Granada Periódico “Ideal”, miércoles 2 de febrero de 1949. El CINECLUB UNIVERSITARIO se crea en 1949 con el nombre de “Cineclub de Granada”. Será en 1953 cuando pase a llamarse con su actual denominación. Así pues en este curso 2018-2019, cumplimos 65 (69) años. 3 ABRIL - MAYO 2019 APRIL - MAY 2019 MAESTROS DEL CINE DE ANIMACIÓN (II): MASTERS OF ANIMATION FILMMAKING (II): LOS UNIVERSOS “MERRIE MELODIES” THE UNIVERSES “MERRIE MELODIES” & “LOONEY TUNES” & “LOONEY TUNES” Viernes 26 abril / Friday 26th april 21 h. FRIGID HARE (Chuck Jones, 1949) Programa nº 1 (1936-1942) [ 70 min. ] FOR SCENT-IMENTAL REASON (Chuck Jones, 1949) RABBIT HOOD (Chuck Jones, 1949) 9 cortometrajes v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles HOMELESS HARE (Chuck Jones, 1950) BUNKER HILL BUNNY (‘Friz’ Freleng, 1950) I LOVE TO SINGA (Tex Avery, 1936) CANARY ROW (‘Friz’ Freleng, 1950) HAVE YOU GOT ANY CASTLES? (Frank Tashlin, 1938) PORKY IN WACKYLAND (Robert Clampett, 1938) THUGS WITH DIRTY MUGS (Tex Avery, 1939) OLD GLORY (Chuck Jones, 1939) Viernes 10 mayo / Friday 10th may 21 h. ELMER’S CANDID CAMERA (Chuck Jones, 1940) Programa nº 4 (1950-1954) [ 70 min. ] YOU OUGHT TO BE IN PICTURES (‘Friz’ Freleng, 1940) 9 cortometrajes HOLLYWOOD STEPS OUT (Tex Avery, 1941) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles THE HEP CAT (Robert Clampett, 1942) RABBIT OF SEVILLE (Chuck Jones, 1950) RABBIT FIRE (Chuck Jones, 1951) FEED THE KITTY (Chuck Jones, 1952) Martes 30 abril / Tuesday 30th april 21 h. RABBIT SEASONING (Chuck Jones, 1952) DON’T GIVE UP THE SHEEP (Chuck Jones, 1953) Programa nº 2 (1943-1948) [ 70 min. -

Classical Music in Carl Stalling's Cartoon Scores

BUGS BUNNY RIDES AGAIN: CLASSICAL MUSIC IN CARL STALLING’S CARTOON SCORES by PAUL MILLER (Under the Direction of Susan Thomas) ABSTRACT Carl Stalling’s musical soundtracks for the mid-20th century Warner Brothers cartoons included frequent quotations from classical composers, including Rossini, Beethoven and Wagner, acquiring a reputation as an informal kind of introductory musical education. Chapter 1 is a general introduction and brief review of some of the recent literature on film and cartoon music. Chapter 2 is a brief historical summary of the use of classical music for film from the days of live accompaniment to silent films through the first decades of recorded synchronous sound films. Chapter 3 examines the musical structure of the soundtrack to the 1948 cartoon Bugs Bunny Rides Again to see how Carl Stalling integrated classical music into his scores. Chapter 4 looks at the broad cultural context of the cartoons at the time of their production and their subsequent reputation as musical education in the decades that followed. Chapter 5 presents some conclusions. INDEX WORDS: Carl Stalling, Cartoon Music BUGS BUNNY RIDES AGAIN: CLASSICAL MUSIC IN CARL STALLING’S CARTOON SCORES by PAUL MILLER B.A., University of Chicago, 1967 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Paul Miller All Rights Reserved BUGS BUNNY RIDES AGAIN: CLASSICAL MUSIC IN CARL STALLING’S CARTOON SCORES by PAUL MILLER Major Professor: Susan Thomas Committee: David Schiller Roger Vogel Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to my Major Professor Susan Thomas for all of her assistance in preparing this thesis, and to my committee members Dr. -

Program Notes | Bugs Bunny at the Symphony II

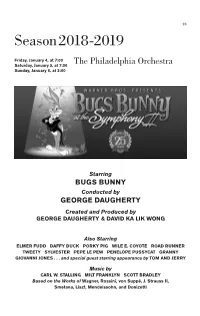

23 Season 2018-2019 Friday, January 4, at 7:00 Saturday, January 5, at 7:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Sunday, January 6, at 2:00 Starring BUGS BUNNY Conducted by GEORGE DAUGHERTY Created and Produced by GEORGE DAUGHERTY & DAVID KA LIK WONG Also Starring ELMER FUDD DAFFY DUCK PORKY PIG WILE E. COYOTE ROAD RUNNER TWEETY SYLVESTER PEPE LE PEW PENELOPE PUSSYCAT GRANNY GIOVANNI JONES . and special guest starring appearance by TOM AND JERRY Music by CARL W. STALLING MILT FRANKLYN SCOTT BRADLEY Based on the Works of Wagner, Rossini, von Suppé, J. Strauss II, Smetana, Liszt, Mendelssohn, and Donizetti 24 Animation Direction by CHUCK JONES FRIZ FRELENG ROBERT CLAMPETT TEX AVERY ROBERT McKIMSON ABE LEVITOW WILLIAM HANNA JOSEPH BARBERA Voice Characterizations by MEL BLANC ARTHUR Q. BRYAN as Elmer Fudd JUNE FORAY HANS CONRIED and NICOLAI SHUTOROV as Giovanni Jones “Rabid Rider” and “Coyote Falls” Directed by MATTHEW O’CALLAGHAN, Music by CHRISTOPHER LENNERTZ Produced in Association with IF/X PRODUCTIONS SAN FRANCISCO Official Website www.BugsBunnyAtTheSymphony.net Original Soundtrack Recording on WATERTOWER MUSIC www.watertower-music.com Follow Bugs Bunny at the Symphony on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. #BugsBunnyAtTheSymphony 25 Program ACT I THE DANCE OF THE COMEDIANS from The Bartered Bride by Bedřich Smetana THE WARNER BROS. FANFARE Music by Max Steiner “MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG” (“The Merrie Melodies Theme”) Music by Charles Tobias, Murray Mencher, and Eddie Cantor Arranged and Orchestrated by Carl W. Stalling “BATON BUNNY” Music by Milt Franklyn Based on the Overture to Morning, Noon, and Night in Vienna by Franz von Suppé Story by Michael Maltese Animation Direction by CHUCK JONES and ABE LEVITOW “SHOW BIZ BUGS” Music by Milt Franklyn “Tea for Two,” music by Vincent Youmans, lyrics by Irving Caesar “Jeepers Creepers” by Harry Warren and Johnny Mercer “Those Endearing Young Charms,” Irish Folk Melody, words by Thomas Moore Story by Warren Foster Animation Direction by FRIZ FRELENG Program continued on next page 26 “RHAPSODY RABBIT” Music by Carl W.